Stagecoach/East Midlands Passenger Rail Franchise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

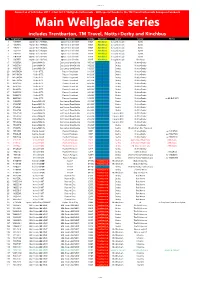

Wellglade Series Includes Trentbarton, TM Travel, Notts+Derby and Kinchbus No

Main series Correct as of 6 October 2017 • Fleet list © Wellglade Enthusiasts • With special thanks to the TM Travel Enthusiasts Group on Facebook Main Wellglade series includes Trentbarton, TM Travel, Notts+Derby and Kinchbus No. Registration Chassis Bodywork Seating Operator Depot Livery Notes 1 YJ07EFR Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 2 YJ07EFS Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 3 YJ07EFT Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 4 YJ07EFU Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 5 YJ07EFV Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 6 YJ07EFW Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 7 YJ07EFX Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Kinchbus 8 YN56FDA Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 9 YN56FDU Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 10 YN56FDZ Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 29 W467BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 30 W474BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 31 W475BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 32 W477BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 33 W291PFS Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H45/30F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 34 W292PFS Volvo B7TL Plaxton President -

Simply the Best Buses in Britain

Issue 100 | November 2013 Y A R N A N I S V R E E R V S I A N R N Y A onThe newsletter stage of Stagecoach Group CELEBRATING THE 100th EDITION OF STAGECOACH GROUP’S STAFF MAGAZINE Continental Simply the best coaches go further MEGABUS.COM has buses in Britain expanded its network of budget services to Stagecoach earns host of awards at UK Bus event include new European destinations, running STAGECOACH officially runs the best services in Germany buses in Britain. for the first time thanks Stagecoach Manchester won the City Operator of to a new link between the Year Award at the recent 2013 UK Bus Awards, London and Cologne. and was recalled to the winner’s podium when it was In addition, megabus.com named UK Bus Operator of the Year. now also serves Lille, Ghent, Speaking after the ceremony, which brought a Rotterdam and Antwerp for number of awards for Stagecoach teams and individuals, the first time, providing even Stagecoach UK Bus Managing Director Robert more choice for customers Montgomery said: “Once again our companies and travelling to Europe. employees have done us proud. megabus.com has also “We are delighted that their efforts in delivering recently introduced a fleet top-class, good-value bus services have been recognised of 10 left-hand-drive 72-seat with these awards.” The Stagecoach Manchester team receiving the City Van Hool coaches to operate Manchester driver John Ward received the Road Operator award. Pictured, from left, are: Operations Director on its network in Europe. -

Student Information Booklet 2021

Student Information Booklet 2021 Dear Students We are so excited to be moving into our new building in September 2021. This information leaflet is designed to introduce you to some key aspects of the building and our move. As you will have seen from our monthly updates, the building development is making great progress and our first group of student building ambassadors are visiting the site this term. Whilst our new building is a fantastic opportunity it is also a huge responsibility and there is some key information in this booklet that should help make our move as smooth as possible. Please do take some time to read through this information with your form tutor and parents. With our new site there will be changes for everyone to get used to. We hope that this guide helps with any questions you may have and any planning you may have to do with travel arrangements. Each form group has two building ambassador that will be your key contact with all aspects relating to the building. They will be there to support you but also remember that all staff are always here to help you with all aspects of school life. For many of you, this new building has felt like a long wait. I also thank you for your patience and encouragement over the years. We look forward to welcoming you into the building and further developing and demonstrating our FAITH values as we take this next step together as Derby Cathedral School. Yours faithfully Mrs J. Brown Headteacher Location The address of our new site is: Derby Cathedral School Great Northern Road Derby DE1 1LR It is situated on Great Northern Road close to the junction with Uttoxeter Road. -

Solent to the Midlands Multimodal Freight Strategy – Phase 1

OFFICIAL SOLENT TO THE MIDLANDS MULTIMODAL FREIGHT STRATEGY – PHASE 1 JUNE 2021 OFFICIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 2. STRATEGIC AND POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................... 11 3. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SOLENT TO THE MIDLANDS ROUTE ........................................................................................................ 28 4. THE ROAD ROUTE ............................................................................................................................................................................. 35 5. THE RAIL ROUTE ............................................................................................................................................................................... 40 6. KEY SECTORS .................................................................................................................................................................................... 50 7. FREIGHT BETWEEN THE SOLENT AND THE MIDLANDS .................................................................................................................... -

Fully Subsidised Services Comments Roberts 120 • Only Service That

167 APPENDIX I INFORMAL CONSULTATION RESPONSES County Council Comments - Fully Subsidised Services Roberts 120 • Only service that goes to Bradgate Park • Service needed by elderly people in Newtown Linford and Stanton under Bardon who would be completely isolated if removed • Bus service also used by elderly in Markfield Court (Retirement Village) and removal will isolate and limit independence of residents • Provides link for villagers to amenities • No other bus service between Anstey and Markfield • Many service users in villages cannot drive and/or do not have a car • Service also used to visit friends, family and relatives • Walking from the main A511 is highly inconvenient and unsafe • Bus service to Ratby Lane enables many vulnerable people to benefit educational, social and religious activities • Many residents both young and old depend on the service for work; further education as well as other daily activities which can’t be done in small rural villages; to lose this service would have a detrimental impact on many residents • Markfield Nursing Care Home will continue to provide care for people with neuro disabilities and Roberts 120 will be used by staff, residents and visitors • Service is vital for residents of Markfield Court Retirement Village for retaining independence, shopping, visiting friends/relatives and medical appointments • Pressure on parking in Newtown Linford already considerable and removing service will be detrimental to non-drivers in village and scheme which will encourage more people to use service Centrebus -

What Is Integrated Ticketing?

Integrated Ticketing Strategy and Delivery Plan INDEX • Executive summary • Background • Current position of Ticketing In Nottinghamshire • Scheme Design, Timeline, Promotion and Governance • Consultation What is Integrated Ticketing? Multi-operator integrated ticketing is an important aspect of realising the County Council’s vision for a better bus service. It makes using buses more convenient, reliable and flexible for passengers, allowing them to use services from a range of operators. Executive Summary The bus network is important as a means to providing accessibility and transport choice to the community, delivering benefits to society including accessibility, transport choice, congestion management, CO2 reductions and helps to stimulate economic growth. The 1985 Transport Act set the scene for the deregulation of the bus industry, and therefore it is essential that bus operations are well integrated and affordable. This Strategy sets out the importance of integrated ticketing to passengers to help sustain a strong and vibrant commercial network. It explains how we move forward towards transport integration in the context of the Nottinghamshire County Council Strategic Plan (2014-2018) 1, Local Transport Plan (up to 2026) 2 and Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) 3 priorities. This will include the legal framework, government policy and guidance and outlines from 2014-2026 Nottinghamshire County Council’s vision for Integrated Ticketing. This document sets out how Integrated Ticketing will be delivered once scheme design, price, partnership arrangements and funding is secured, with an ambitious timeline for implementation. Background The use of public transport is important to tackle congestion, rising CO2 levels and improving access to employment, training, health, leisure and shopping opportunities. -

Competitive Tendering of Rail Services EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of MINISTERS of TRANSPORT (ECMT)

Competitive EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT Tendering of Rail Competitive tendering Services provides a way to introduce Competitive competition to railways whilst preserving an integrated network of services. It has been used for freight Tendering railways in some countries but is particularly attractive for passenger networks when subsidised services make competition of Rail between trains serving the same routes difficult or impossible to organise. Services Governments promote competition in railways to Competitive Tendering reduce costs, not least to the tax payer, and to improve levels of service to customers. Concessions are also designed to bring much needed private capital into the rail industry. The success of competitive tendering in achieving these outcomes depends critically on the way risks are assigned between the government and private train operators. It also depends on the transparency and durability of the regulatory framework established to protect both the public interest and the interests of concession holders, and on the incentives created by franchise agreements. This report examines experience to date from around the world in competitively tendering rail services. It seeks to draw lessons for effective design of concessions and regulation from both of the successful and less successful cases examined. The work RailServices is based on detailed examinations by leading experts of the experience of passenger rail concessions in the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. It also -

UNECE Tram and Metro Statistics Metadata Introduction File Structure

UNECE Tram and Metro Statistics Metadata Introduction This file gives detailed country notes on the UNECE tram and metro statistics dataset. These metadata describe how countries have compiled tram and metro statistics, what the data cover, and where possible how passenger numbers and passenger-km have been determined. Whether data are based on ticket sales, on-board sensors or another method may well affect the comparability of passenger numbers across systems and countries, hence it being documented here. Most of the data are at the system level, allowing comparisons across cities and systems. However, not every country could provide this, sometimes due to confidentiality reasons. In these cases, sometimes either a regional figure (e.g. the Provinces of Canada, which mix tram and metro figures with bus and ferry numbers) or a national figure (e.g. Czechia trams, which excludes the Prague tram system) have been given to maximise the utility of the dataset. File Structure The disseminated file is structured into seven different columns, as follows: Countrycode: These are United Nations standard country codes for statistical use, based on M49. The codes together with the country names, region and other information are given here https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/overview/ (and can be downloaded as a CSV directly here https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/overview/#). City: This column gives the name of the city or region where the metro or tram system operates. In many cases, this is sufficient to identify the system. In some cases, non-roman character names have been converted to roman characters for convenience. -

UK BUS Operating Review 2003

‘‘I’ve looked after travelling passengers for 10 years now and know that, above all, our customers value good communication. If services don’t run smoothly, they like to be kept informed. Keeping our passengers happy is crucial to our success.’’ Chris Pearce Standards Controller UK Bus Operating review 2003 UK BUS Outside London, total passenger volumes have increased by Stagecoach continues to be one of the leading UK bus operators, 0.4%. The trend in passenger volumes varies significantly by with a 16% share of a highly competitive market. Our UK Bus geographical area. We have initiatives in place to encourage business, the traditional core of the Group, remains a strong further growth and we have been particularly successful in source of cash flow. As one of the biggest bus operators in the increasing volumes in areas where congestion is causing some UK, we are at the cutting edge in developing new and innovative commuters to switch to using public transport. products and we are committed to playing a key part in Our major operation at Ferrytoll Park and Ride in Fife, Scotland, achieving the Government’s objectives of increased use of public which at peak times runs buses every five minutes into transport and greater integration. Edinburgh, has seen passenger volumes increase by 30% in the Turnover in our UK Bus division has increased by 5.4% to »598.4m past year. The Scottish Executive has approved additional (2002 ^ »567.9m). Operating profit was »67.0m,* compared to investment to double the size of the facility to 1,000 car parking »62.7m in the previous year, and this is after taking account of spaces. -

Sheffield City Council Place Report to City Centre

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL PLACE 8 REPORT TO CITY CENTRE SOUTH AND EAST PLANNING DATE 19/12/2011 AND HIGHWAYS COMMITTEE REPORT OF DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT SERVICES ITEM SUBJECT APPLICATIONS UNDER VARIOUS ACTS/REGULATIONS SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS SEE RECOMMENDATIONS HEREIN THE BACKGROUND PAPERS ARE IN THE FILES IN RESPECT OF THE PLANNING APPLICATIONS NUMBERED. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS N/A PARAGRAPHS CLEARED BY BACKGROUND PAPERS CONTACT POINT FOR Lucy Bond TEL 0114 2734556 ACCESS Chris Heeley NO: 0114 2736329 AREA(S) AFFECTED CATEGORY OF REPORT OPEN 2 Application No. Location Page No. 10/01737/FUL 272 Glossop Road Sheffield 6 S10 2HS 11/01396/FUL NUM Headquarters Holly Building 13 Holly Street Sheffield S1 2GT 11/01864/FUL Site Of Gordon Lamb Limited 10 Summerfield Street 24 Sheffield S11 8HJ 11/02379/FUL 29 Glover Road Totley 51 Sheffield S17 4HN 11/02515/FUL 56 High Storrs Drive Sheffield 57 S11 7LL 11/02727/FUL 39 Firth Park Crescent Sheffield 64 S5 6HD 11/02801/REM Park Hill Flats Park Hill Estate 69 Duke Street And Talbot Street Sheffield S2 5RQ 11/02883/FUL Brentwood Lawn Tennis Club Brentwood Road 90 Sheffield S11 9BU 3 11/03115/FUL Scarsdale Grange Nursing Home 139 Derbyshire Lane 97 Sheffield S8 9EQ 11/03197/LBC Park Hill Estate Duke Street 108 Park Hill Sheffield S2 5RQ 11/03361/FUL 51-53 Stanley Street Sheffield 110 S3 8HH 11/03601/FUL SOYO 117 Rockingham Street 123 Sheffield S1 4EB 4 5 SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Report Of The Head Of Planning To The CITY CENTRE AND EAST Planning And Highways Committee Date Of Meeting: 19/12/2011 LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS FOR DECISION OR INFORMATION *NOTE* Under the heading “Representations” a Brief Summary of Representations received up to a week before the Committee date is given (later representations will be reported verbally). -

What Light Rail Can Do for Cities

WHAT LIGHT RAIL CAN DO FOR CITIES A Review of the Evidence Final Report: Appendices January 2005 Prepared for: Prepared by: Steer Davies Gleave 28-32 Upper Ground London SE1 9PD [t] +44 (0)20 7919 8500 [i] www.steerdaviesgleave.com Passenger Transport Executive Group Wellington House 40-50 Wellington Street Leeds LS1 2DE What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence Contents Page APPENDICES A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK B Overseas Experience C People Interviewed During the Study D Full Bibliography P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence APPENDIX A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence A1. TYNE & WEAR METRO A1.1 The Tyne and Wear Metro was the first modern light rail scheme opened in the UK, coming into service between 1980 and 1984. At a cost of £284 million, the scheme comprised the connection of former suburban rail alignments with new railway construction in tunnel under central Newcastle and over the Tyne. Further extensions to the system were opened to Newcastle Airport in 1991 and to Sunderland, sharing 14 km of existing Network Rail track, in March 2002. -

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (New Entries First with Older Entries Retained Underneath)

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (new entries first with older entries retained underneath) Now go back to: Home Page Introduction or on to: The Best Timetables of the British Isles Summary of the use of the 24-hour clock Links Section English Counties Welsh Counties, Scottish Councils, Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, Channel Islands and Isle of Man Bus Operators in the British Isles Rail Operators in the British Isles SEPTEMBER 25 2021 – FIRST RAIL RENEWS SPONSORSHIP I am pleased to announce that First Rail (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-rail.aspx) has renewed its sponsorship of my National Rail Passenger Operators' map and the Rail section of this site, thereby covering GWR, Hull Trains, Lumo, SWR and TransPennine Express, as well as being a partner in the Avanti West Coast franchise. This coincides with the 50th edition of the map, published today with an October date to reflect the start of Lumo operations. I am very grateful for their support – not least in that First Bus (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-bus.aspx) is already a sponsor of this website. JULY 01 2021 – THE FIRST 2021 WELSH AUTHORITY TIMETABLE Whilst a number of authorities in SW England have produced excellent summer timetable books – indeed some produced them throughout the pandemic – for a country that relies heavily on tourism Wales is doing an utterly pathetic job, with most of the areas that used to have good books simply saying they don’t expect to publish anything until the autumn or the winter – or, indeed that they have no idea when they’ll re-start (see the entries in Welsh Counties section).