Chapter 12 Bryophytes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translocation and Transport

Glime, J. M. 2017. Nutrient Relations: Translocation and Transport. Chapt. 8-5. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. 8-5-1 Physiological Ecology. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 17 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 8-5 NUTRIENT RELATIONS: TRANSLOCATION AND TRANSPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Translocation and Transport ................................................................................................................................ 8-5-2 Movement from Older to Younger Tissues .................................................................................................. 8-5-6 Directional Differences ................................................................................................................................ 8-5-8 Species Differences ...................................................................................................................................... 8-5-8 Mechanisms of Transport .................................................................................................................................... 8-5-9 Source to Sink? ............................................................................................................................................ 8-5-9 Enrichment Effects ..................................................................................................................................... 8-5-10 Internal Transport -

Wild Species 2010 the GENERAL STATUS of SPECIES in CANADA

Wild Species 2010 THE GENERAL STATUS OF SPECIES IN CANADA Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council National General Status Working Group This report is a product from the collaboration of all provincial and territorial governments in Canada, and of the federal government. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 302 pp. Available in French under title: Espèces sauvages 2010: La situation générale des espèces au Canada. ii Abstract Wild Species 2010 is the third report of the series after 2000 and 2005. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide an overview on which species occur in Canada, in which provinces, territories or ocean regions they occur, and what is their status. Each species assessed in this report received a rank among the following categories: Extinct (0.2), Extirpated (0.1), At Risk (1), May Be At Risk (2), Sensitive (3), Secure (4), Undetermined (5), Not Assessed (6), Exotic (7) or Accidental (8). In the 2010 report, 11 950 species were assessed. Many taxonomic groups that were first assessed in the previous Wild Species reports were reassessed, such as vascular plants, freshwater mussels, odonates, butterflies, crayfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Other taxonomic groups are assessed for the first time in the Wild Species 2010 report, namely lichens, mosses, spiders, predaceous diving beetles, ground beetles (including the reassessment of tiger beetles), lady beetles, bumblebees, black flies, horse flies, mosquitoes, and some selected macromoths. The overall results of this report show that the majority of Canada’s wild species are ranked Secure. -

Species Summary Table

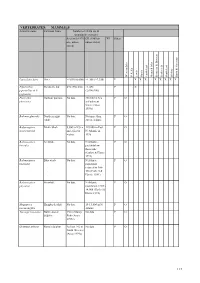

VERTEBRATES: MAMMALS Scientific name Common Name Number of 10 km sqs & (population estimate) Scotland (1970 GB (1960 on WI Status on - unless unless stated) stated) Western Isles St Kilda Lewis Harris North Uist Monach Isles Berneray & Boreray Benbecula South Uist Eriskay Barra & Vatersay Lutra lutra lutra Otter >1,050 (6,600) >1,308 (>7,350) P X X X X X X X X Pipistrellus Pipistrelle bat 492 (550,000) >1,438 P X pipisterllus & P. (2,000,000) pygmaeus Phocoena Harbour porpoise No data 350,000 in Sea P O phocoena and adjacent waters (Anon 1999a) Balaena glacialis Northern right No data Not more than P O whale 300 in Atlantic Balaenoptera Minke whale 8,500 in N Sea 110,000 in East P O acutorostrata and adjacent N. Atlantic in waters 1995 Balaenoptera Sei whale No data N Atlantic - P O borealis probably low thousands (Corbet & Harris 1991) Balaenoptera Blue whale No data N Atlantic P O musculus population reduced to 300- 500 (Corbett & Harris 1991) Balaenoptera Fin whale No data N Atlantic P O physalus population 9,000 - 14,000 (Corbet & Harris 1991) Megaptera Humpback whale No data 10-15,000 in N P O novaeangilea Atlantic Tursiops truncatus Bottle-nosed 130 in Moray No data P O dolphin Firth (Anon 1999a) Grampus griseus Risso's dolphin At least 142 in No data P O North Minches (Anon 1999a) 113 VERTEBRATES: MAMMALS Scientific name Common Name Number of 10 km sqs & (population estimate) Scotland (1970 GB (1960 on WI Status on - unless unless stated) stated) Western Isles St Kilda Lewis Harris North Uist Monach Isles Berneray & Boreray Benbecula -

Checklists of Protected and Threatened Species in Ireland

ISSN 1393 – 6670 N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE CHECKLISTS OF PROTECTED AND THREATENED SPECIES IN IRELAND Brian Nelson, Sinéad Cummins, Loraine Fay, Rebecca Jeffrey, Seán Kelly, Naomi Kingston, Neil Lockhart, Ferdia Marnell, David Tierney and Mike Wyse Jackson I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 116 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) commissions a range of reports from external contractors to provide scientific evidence and advice to assist it in its duties. The Irish Wildlife Manuals series serves as a record of work carried out or commissioned by NPWS, and is one means by which it disseminates scientific information. Others include scientific publications in peer reviewed journals. The views and recommendations presented in this report are not necessarily those of NPWS and should, therefore, not be attributed to NPWS. Front cover, small photographs from top row: Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; Red Squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Eddie Dunne, NPWS Image Library; Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia, Brian Nelson; Puffin Fratercula arctica, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; Long Range and Upper Lake, Killarney National Park, NPWS Image Library; Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Barn Owl Tyto alba, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson Main photograph: Short-beaked Common Dolphin Delphinus delphis, -

A Revised Red List of Bryophytes in Britain

ConservationNews Revised Red List distinguished from Extinct. This Red List uses Extinct in the Wild (EW) – a taxon is Extinct version 3.1 of the categories and criteria (IUCN, in the Wild when it is known to survive only in A revised Red List of 2001), along with guidelines produced to assist cultivation or as a naturalized population well with their interpretation and use (IUCN, 2006, outside the past range. There are no taxa in this 2008), further guidelines for using the system category in the British bryophyte flora. bryophytes in Britain at a regional level (IUCN, 2003), and specific Regionally Extinct (RE) – a taxon is regarded guidelines for applying the system to bryophytes as Regionally Extinct in Britain if there are no (Hallingbäck et al., 1995). post-1979 records and all known localities have Conservation OfficerNick Hodgetts presents the latest revised Red List for How these categories and criteria have been been visited and surveyed without success, or interpreted and applied to the British bryophyte if colonies recorded post-1979 are known to bryophytes in Britain. Dumortiera hirsuta in north Cornwall. Ian Atherton flora is summarized below, but anyone interested have disappeared. It should be appreciated that in looking into them in more depth should regional ‘extinction’ for bryophytes is sometimes he first published Red List of et al. (2001) and Preston (2010), varieties and consult the original IUCN documents, which less final than for other, more conspicuous bryophytes in Britain was produced subspecies have been disregarded. are available on the IUCN website (www. organisms. This may be because bryophytes are in 2001 as part of a Red Data Book 1980 has been chosen as the cut-off year to iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/categories- easily overlooked, or because their very efficient for bryophytes (Church et al., 2001). -

Biodiverse Master

Montane, Heath and Bog Habitats MONTANE, HEATH AND BOG HABITATS CONTENTS Montane, heath and bog introduction . 66 Opportunities for action in the Cairngorms . 66 The main montane, heath and bog biodiversity issues . 68 Main threats to UK montane, heath and bog Priority species in the Cairngorms . 72 UK Priority species and Locally important species accounts . 73 Cairngorms montane, heath and bog habitat accounts: • Montane . 84 • Upland heath . 87 • Blanket bog . 97 • Raised bog . 99 ‘Key’ Cairngorms montane, heath and bog species . 100 65 The Cairngorms Local Biodiversity Action Plan MONTANE, HEATH AND BOG INTRODUCTION Around one third of the Cairngorms Partnership area is over 600-650m above sea level (above the natural woodland line, although this is variable from place to place.). This comprises the largest and highest area of montane habitat in Britain, much of which is in a relatively pristine condition. It contains the main summits and plateaux with their associated corries, rocky cliffs, crags, boulder fields, scree slopes and the higher parts of some glens and passes. The vegeta- tion is influenced by factors such as exposure, snow cover and soil type. The main zone is considered to be one of the most spectacular mountain areas in Britain and is recognised nationally and internationally for the quality of its geology, geomorphology and topographic features, and associated soils and biodiversity. c14.5% of the Cairngorms Partnership area (75,000ha) is land above 600m asl. Upland heathland is the most extensive habitat type in the Cairngorms Partnership area, covering c41% of the area, frequently in mosaics with blanket bog. -

Floristic Study of Bryophytes in a Subtropical Forest of Nabeup-Ri at Aewol Gotjawal, Jejudo Island

− pISSN 1225-8318 Korean J. Pl. Taxon. 48(1): 100 108 (2018) eISSN 2466-1546 https://doi.org/10.11110/kjpt.2018.48.1.100 Korean Journal of ORIGINAL ARTICLE Plant Taxonomy Floristic study of bryophytes in a subtropical forest of Nabeup-ri at Aewol Gotjawal, Jejudo Island Eun-Young YIM* and Hwa-Ja HYUN Warm Temperate and Subtropical Forest Research Center, National Institute of Forest Science, Seogwipo 63582, Korea (Received 24 February 2018; Revised 26 March 2018; Accepted 29 March 2018) ABSTRACT: This study presents a survey of bryophytes in a subtropical forest of Nabeup-ri, known as Geumsan Park, located at Aewol Gotjawal in the northwestern part of Jejudo Island, Korea. A total of 63 taxa belonging to Bryophyta (22 families 37 genera 44 species), Marchantiophyta (7 families 11 genera 18 species), and Antho- cerotophyta (1 family 1 genus 1 species) were determined, and the liverwort index was 30.2%. The predominant life form was the mat form. The rates of bryophytes dominating in mesic to hygric sites were higher than the bryophytes mainly observed in xeric habitats. These values indicate that such forests are widespread in this study area. Moreover, the rock was the substrate type, which plays a major role in providing micro-habitats for bryophytes. We suggest that more detailed studies of the bryophyte flora should be conducted on a regional scale to provide basic data for selecting indicator species of Gotjawal and evergreen broad-leaved forests on Jejudo Island. Keywords: bryophyte, Aewol Gotjawal, liverwort index, life-form Jejudo Island was formed by volcanic activities and has geological, ecological, and cultural aspects (Jeong et al., 2013; unique topological and geological features. -

Phylogenetic and Morphological Notes on Uleobryum Naganoi Kiguchi Et Ale (Pottiaceae, Musci) 1

HikobiaHikobial4:143-147.2004 14: 143-147.2004 PhylogeneticPhylO窪eneticandmorphOlO=icalmtesⅢIノルCD〃"剛〃昭肌oiKiguchi and morphological notes on Uleobryum naganoi Kiguchi eteraL(POttiaceae,Musci)’ ale (Pottiaceae, Musci) 1 HIROYUKIHIRoYuKISATQHⅡRoMITsuBoTA,ToMIoYAMAGucHIANDHIRoNoRIDEGucH1 SATO, HIROMI TSUBOTA, TOMIO YAMAGUCHI AND HIRONORI DEGUCHI SATO,SATO,H、,TsuBoTA,H、,YAMAGucHI,T、&DEGucHI,H2004Phylogeneticandmor- H., TSUBOTA, H., YAMAGUCHI, T. & DEGUCHI, H. 2004. Phylogenetic and mor phologicalphologicalnotesonU/eo6Mイノ'z〃αgα"ojKiguchietα/、(Pottiaceae,Musci)Hikobia notes on Uleobryum naganoi Kiguchi et al. (Pottiaceae, Musci). Hikobia 14:l4:143-147. 143-147. UleobryumU/eo6/Wm〃αgα"ojKiguchiejα/、,endemictoJapanwithalimitednumberofknown naganoi Kiguchi et aI., endemic to Japan with a limited number of known locations,locations,isnewlyreportedffomShikoku,westernJapanThroughcarefUlexamina- is newly reported from Shikoku, western Japan. Through careful examina tionoffTeshmaterial,rhizoidalmberfbnnationisconfinnedfbrthefirsttime・The , tion of fresh material, rhizoidal tuber formation is confirmed for the first time. The phylogeneticphylogeneticpositionofthiscleistocalpousmossisalsoassessedonthebasisofmaxi- position of this cleistocarpous moss is also assessed on the basis of maxi mummumlikelihoodanalysisof′bcLgenesequences、ThecuITentpositioninthePot- likelihood analysis of rbcL gene sequences. The current position in the Pot tiaceaetiaceaeissUpportedandacloserelationshiptoEpheme'wmslpj""/OS"川ssuggested is supported and a close relationship to -

On the Genus Hedwigia (Hedwigiaceae, Bryophyta) in Russia К Систематике Рода Hedwigia (Hedwigiaceae, Bryophyta) В России Elena A

Arctoa (2016) 25: 241–277 doi: 10.15298/arctoa.25.20 ON THE GENUS HEDWIGIA (HEDWIGIACEAE, BRYOPHYTA) IN RUSSIA К СИСТЕМАТИКЕ РОДА HEDWIGIA (HEDWIGIACEAE, BRYOPHYTA) В РОССИИ ELENA A. IGNATOVA1, OXANA I. KUZNETSOVA2, VLADIMIR E. FEDOSOV1 & MICHAEL S. IGNATOV1,2 ЕЛЕНА А. ИГНАТОВА1, ОКСАНА И. КУЗНЕЦОВА2, ВЛАДИМИР Э. ФЕДОСОВ1, МИХАИЛ С. ИГНАТОВ1,2 Abstract An integrative molecular and morphological study of the genus Hedwigia in Russia revealed at least five distinct species in its territory. Hedwigia czernyadjevae sp. nov. appears to have a wide distribution in Transbaikalia, Yakutia and high mountains of the Russian Far East, although it never occurs frequently. Previously its specimens were identified as H. stellata, but straight leaf apices, strongly incrassate and porose laminal cells and hairy calyptrae differentiate H. czernyadjevae from this species, in addition to sequence data, which place the Siberian species closer to American H. detonsa. Hedwigia nemoralis sp. nov. occurs in southern regions of Russia, from the Caucasus to the Russian Far East, with one locality in Central European Russia. It was also revealed from eastern North America. It is characterized by a small plant size, shortly acuminate, secund leaves with short, denticulate hyaline hair points and weakly ciliate perichaetial leaves. Hedwigia mollis sp. nov. has shortly recurved leaf margins, weakly sinuose laminal cells and spores 20–25(–28) m. It was re- vealed in European Russia, from the southern Murmansk Province and Karelia to the Caucasus, and from South Urals and Altai Mts. Hedwigia ciliata is infrequent in Russia, occurring mainly in the North-Western European Russia, with few localities in its central part. -

Bryophytes of Adjacent Serpentine and Granite Outcrops on the Deer Isles, Maine, U.S.A

RHODORA, Vol. 111, No. 945, pp. 1–20, 2009 E Copyright 2009 by the New England Botanical Club BRYOPHYTES OF ADJACENT SERPENTINE AND GRANITE OUTCROPS ON THE DEER ISLES, MAINE, U.S.A. LAURA R. E. BRISCOE The Field Museum, 1400 South Lakeshore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605 TANNER B. HARRIS University of Massachusetts, Fernald Hall, 270 Stockbridge Road, Amherst, MA 01003 WILLIAM BROUSSARD University of Maine, 421 Estabrooke Hall, Orono, ME 04469 1 EVA DANNENBERG,FRED C. OLDAY, AND NISHANTA RAJAKARUNA College of the Atlantic, 105 Eden Street, Bar Harbor, ME 04609 1Author for Correspondence; Current Address: Department of Biological Sciences, One Washington Square, San Jose´ State University, San Jose´, CA 95192-0100 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. The serpentine-substrate effect is well documented for vascular plants, but the literature for bryophytes is limited. The majority of literature on bryophytes in extreme geoedaphic habitats focuses on the use of species as bioindicators of industrial pollution. Few attempts have been made to characterize bryophyte floras on serpentine soils derived from peridotite and other ultramafic rocks. This paper compares the bryophyte floras of both a peridotite and a granite outcrop from the Deer Isles, Hancock County, Maine, and examines tissue elemental concentrations for select species from both sites. Fifty-five species were found, 43 on serpentine, 26 on granite. Fourteen species were shared in common. Twelve species are reported for the first time from serpentine soils. Tissue analyses indicated significantly higher Mg, Ni, and Cr concentrations and significantly lower Ca:Mg ratios for serpentine mosses compared to those from granite. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Chinese Thuidiaceae with Emphasis on Thuidium and Pelekium

Molecular Phylogeny of Chinese Thuidiaceae with emphasis on Thuidium and Pelekium QI-YING, CAI1, 2, BI-CAI, GUAN2, GANG, GE2, YAN-MING, FANG 1 1 College of Biology and the Environment, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China. 2 College of Life Science, Nanchang University, 330031 Nanchang, China. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We present molecular phylogenetic investigation of Thuidiaceae, especially on Thudium and Pelekium. Three chloroplast sequences (trnL-F, rps4, and atpB-rbcL) and one nuclear sequence (ITS) were analyzed. Data partitions were analyzed separately and in combination by employing MP (maximum parsimony) and Bayesian methods. The influence of data conflict in combined analyses was further explored by two methods: the incongruence length difference (ILD) test and the partition addition bootstrap alteration approach (PABA). Based on the results, ITS 1& 2 had crucial effect in phylogenetic reconstruction in this study, and more chloroplast sequences should be combinated into the analyses since their stability for reconstructing within genus of pleurocarpous mosses. We supported that Helodiaceae including Actinothuidium, Bryochenea, and Helodium still attributed to Thuidiaceae, and the monophyletic Thuidiaceae s. lat. should also include several genera (or species) from Leskeaceae such as Haplocladium and Leskea. In the Thuidiaceae, Thuidium and Pelekium were resolved as two monophyletic groups separately. The results from molecular phylogeny were supported by the crucial morphological characters in Thuidiaceae s. lat., Thuidium and Pelekium. Key words: Thuidiaceae, Thuidium, Pelekium, molecular phylogeny, cpDNA, ITS, PABA approach Introduction Pleurocarpous mosses consist of around 5000 species that are defined by the presence of lateral perichaetia along the gametophyte stems. Monophyletic pleurocarpous mosses were resolved as three orders: Ptychomniales, Hypnales, and Hookeriales (Shaw et al. -

Hypnaceaeandpossiblyrelatedfn

Hikobial3:645-665.2002 Molecularphylo窪enyOfhypnobrJ/aleanmOssesasin化rredfroma lar淫e-scaledatasetofchlOroplastlbcL,withspecialre他rencetothe HypnaceaeandpOssiblyrelatedfnmilies1 HIRoMITsuBoTA,ToMoTsuGuARIKAwA,HIRoYuKIAKIYAMA,EFRAINDELuNA,DoLoREs GoNzALEz,MASANoBuHIGucHIANDHIRoNoRIDEGucHI TsuBoTA,H、,ARIKAwA,T,AKIYAMA,H,,DELuNA,E,GoNzALEz,,.,HIGucHI,M 4 &DEGucHI,H、2002.Molecularphylogenyofhypnobryaleanmossesasinferred fiPomalarge-scaledatasetofchloroplastr6cL,withspecialreferencetotheHypnaceae andpossiblyrelatedfamiliesl3:645-665. ▲ Phylogeneticrelationshipswithinthehypnobryaleanmosses(ie,theHypnales,Leuco- dontales,andHookeriales)havebeenthefbcusofmuchattentioninrecentyears Herewepresentphylogeneticinfierencesonthislargeclade,andespeciallyonthe Hypnaceaeandpossiblyrelatedftlmilies,basedonmaximumlikelihoodanalysisof l81r6cLsequences、Oursmdycorroboratesthat(1)theHypnales(sstr.[=sensu Vittl984])andLeucodontalesareeachnotmonophyleticentities、TheHypnalesand LeucodontalestogethercompriseawellsupportedsistercladetotheHookeriales;(2) theSematophyllaceae(s」at[=sensuTsubotaetaL2000,2001a,b])andPlagiothecia‐ ceae(s・str.[=sensupresentDareeachresolvedasmonophyleticgroups,whileno particularcladeaccommodatesallmembersoftheHypnaceaeandCryphaeaceae;and (3)theHypnaceaeaswellasitstypegenusノリDlwz"川tselfwerepolyphyletioThese resultsdonotconcurwiththesystemsofVitt(1984)andBuckandVitt(1986),who suggestedthatthegroupswithasinglecostawouldhavedivergedfiFomthehypnalean ancestoratanearlyevolutionarystage,fbllowedbythegroupswithadoublecosta (seealsoTsubotaetall999;Bucketal2000)OurresultsfiPomlikelihoodanalyses