Some Remarks on Their Features and Functions in Tibet Nicola Schneider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

Palpung Changchub Dargye Ling Prayer Book

Palpung Changchub Dargyeling REFUGE (x3) SANG GYE CHO DANG TSOK KYI CHOK NAM LA Until enlightenment I take refuge, JANG CHUB BAR DU DAK NI KYAB SU CHI in the Buddha, Dharma and the Supreme Assembly, DAK GI JIN SOK GYI PAY SO NAM KYI May the merits from my generosity and other good deeds, DRO LA PEN CHIR SANG GYE DRUP PAR SHOK result in Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings FOUR IMMEASURABLES SEM CHEN TAM CHE DE WA DANG DE WAY GYU DANG DEN PAR GYUR CHIK May all beings have happiness and the causes of happiness, DUK NGAL DANG DUK NGAL GYI GYU DAN DREL WAY GYUR CHIK May all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering, DUK NGAL ME PAY DE WA DAM PA DANG MI DRAL WAR GYUR CHIK May all beings never be separate from the supreme bliss which is free from all suffering, NYE RING CHAK DANG NYI DANG DREL WAY TANG NYOM CHEN PO LA NAY PAR GYUR CHIK May all beings live in the Great Equanimity free from all attachment and aversion PRAYER TO THE ROOT LAMA PAL DEN TSAWI LAMA RINPOCHE, DA KI CHI WOR PE DE DEN CHU LA Wonderful, precious Root Guru, seated on a lotus and moon seat above my head, KA DRIN CHEN PEU GO NAY JAY ZUNG TAY I pray that you take me into your care with your vast kindness, KU SUNG TUK JI NGO DRUP TSAL DU SOL And give me the siddhis of body, speech and mind. 2 Palpung Changchub Dargyeling THE SEVEN BRANCH PRAYER CHANG TSAL WA TANG CHURSHING SHAG PA DANG We prostrate and make offerings JESU YIR ANG KULCHI SOL WA YI We confess and rejoice in the virtues of all beings GEWA CHUNG ZEY DAGI CHI SAGPA We ask for the wheel of Dharma to be turned for all beings TAN CHE DZOG PEY CHANG CHUP CHEN POR NGO We pray that the Buddhas remain in this world to teach, We dedicate all merit to sentient beings. -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible. -

1 Phün Tsok Ge Lek Che Wai Trün Pey Ku Thar

SONGS OF SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE - Condensed Points of the Stages of the Path - lam rim nyams mgur - by Je Tsongkapa 1 PHÜN TSOK GE LEK CHE WAI TRÜN PEY KU THAR YE DRO WAI RE WA KONG WEY SUNG MA LÜ SHE JA JI ZHIN ZIK PEY THUK SHA KYEY TSO WO DE LA GO CHAK TSEL Your body is created from a billion perfect factors of goodness; Your speech satisfies the yearnings of countless sentient beings; Your mind perceives all objects of knowledge exactly as they are – I bow my head to you O chief of the Shakya clan. 2 DA ME TÖN PA DE YI SE KYI CHOK GYAL WAI DZE PA KÜN GYI KUR NAM NE DRANG ME ZHING DU TRÜL WAI NAM RÖL PA MI PAM JAM PAI YANG LA CHAK TSEL LO You’re the most excellent sons of such peerless teacher; You carry the burden of the enlightened activities of all conquerors, And in countless realms you engage in ecstatic display of emanations – I pay homage to you O Maitreya and Manjushri. 3 SHIN TU PAK PAR KAR WA GYAL WAI YUM JI ZHIN GONG PA DREL DZE DZAM LING GYEN LU DRUB THOK ME CHE NI SA SUM NA YONG SU TRAK PEY ZHAB LA DAG CHAK TSEL So difficult to fathom is the mother of all conquerors, You who unravel its contents as it is are the jewels of the world; You’re hailed with great fame in all three spheres of the world – I pay homage to you O Nagarjuna and Asanga. -

̱ ͵͵ ̱ Special Non-Finite Forms of Latin and Albanian

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 4 No.4 ISSN 2240-0524 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy June 2014 Special Non-Finite Forms of Latin and Albanian Dr. Leonard Xhamani Docente di Latino, Università di Tirana Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n4p373 Abstract The verbal system of Latin language, just like that of Albanian, apart from the finite forms, is characterized by a number of non- finite forms, which make this system more complete and diverse. In this speech, we will be focused on a special non- finite form of Latin, that of supinum, which has no relevant structure in Albanian. We will see the supinum according to its way of formation and its noun and verb features. The examples that illustrate this non-finite form of Latin will be translated, in order to have a better understanding of the verbal forms of Albanian which correspond to it. An important part in this speech will be occupied by the Albanian non-finite forms, of the type me tɺ ardhur dhe njɺ ardhur, observing not only their way of formation and the function they have, but also how they can be expressed in Latin. However, according to their structural type and grammatical values, these two forms have no relevant ones in Latin, but they can be expressed by some structures including the participle. The method used is that of the approach, a well- known method in Linguistics, which through the comparison of different elements, not only within a language, but also between different languages, permits the analyses and the comparative outlook. -

Amitabha Sadhana Tibetan-Eng

The Meditation and Recitation of Amitabha called Uniting with the Pure Land of Sukhavati Land of Pure Uniting with the Recitation of Amitabha called Meditation and The ALTRUISTIC MOTIVATION DHAG-LA DANG-WAR JYE-PAY DRA/ NO-PAR JYE-PAY GEG/ THAR-PA DANG THAM-CHE KHYEN-PAY BAR-DU CHO-PAR All mother sentient beings, especially those enemies who hate me, obstructors who harm me, and those who 1 JYE-PA TAM-CHE KYI TSO JYE-PAY/ MA NAM KHA DANG NYAM-PAY SEM-CHEN TAM-CHE DEWA DANG-DEN/ create obstacles on my path to liberation and all-knowingness; may they experience happiness, DHUG-NYAL DANG DREL NYUR-DU LA-NA ME-PA YANG DAG-PAR DZOG-PAY JYANG-CHUB RINPOCHE THOB-PAR-JYA/ and be separated from suffering. I will quickly establish them in the state of the most perfect and precious Buddhahood. (repeat 3 times) The Meditation and Recitation of Amitabha called Uniting with the Pure Land of Sukhavati Land of Pure Uniting with the Recitation of Amitabha called Meditation and The ACTION BODHICITTA PRAYER DEI CHE-DU SANG MA-GYE KYI BARDU LU-NGAG YI-SUM GEWA-LA KOL/ Thus until I achieve enlightenment, I perform virtuous deeds with body, speech and mind. 2 MA-SHEI BARDU LU NGAG YI-SUM GEWA-LA KOL/ Until death, I perform virtuous deeds with body, speech and mind. DU DE-RING-NE SUNG-TE NYI- MA SANG DA TSAM-GYI BARDU LU NGAG YI-SUM GEWA-LA KOL/ From now, until this time tomorrow, I perform virtuous deeds with body, speech and mind. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

TLD: Сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012

TLD: сайт Script Identifier: Cyrillic Script Description: Cyrillic Unicode (Basic, Extended-A and Extended-B) Version: 1.0 Effective Date: 02 April 2012 Registry: сайт Registry Contact: Iliya Bazlyankov <[email protected]> Tel: +359 8 9999 1690 Website: http://www.corenic.org This document presents a character table used by сайт Registry for IDN registrations in Cyrillic script. The policy disallows IDN variants, but prevents registration of names with potentially similar characters to avoid any user confusion. U+002D;U+002D # HYPHEN-MINUS -;- U+0030;U+0030 # DIGIT ZERO 0;0 U+0031;U+0031 # DIGIT ONE 1;1 U+0032;U+0032 # DIGIT TWO 2;2 U+0033;U+0033 # DIGIT THREE 3;3 U+0034;U+0034 # DIGIT FOUR 4;4 U+0035;U+0035 # DIGIT FIVE 5;5 U+0036;U+0036 # DIGIT SIX 6;6 U+0037;U+0037 # DIGIT SEVEN 7;7 U+0038;U+0038 # DIGIT EIGHT 8;8 U+0039;U+0039 # DIGIT NINE 9;9 U+0430;U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A а;а U+0431;U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE б;б U+0432;U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE в;в U+0433;U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GHE г;г U+0434;U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE д;д U+0435;U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE е;е U+0436;U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE ж;ж U+0437;U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE з;з U+0438;U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER I и;и U+0439;U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT I й;й U+043A;U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA к;к U+043B;U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL л;л U+043C;U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM м;м U+043D;U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN н;н U+043E;U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O о;о U+043F;U+043F -

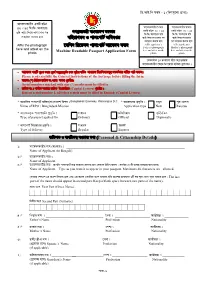

MRP Application Form

¢X.BC.¢f glj - 1 (¢he¡j¨−mÉ fÊ¡fÉ) A¡−hceL¡l£l HL¢V l¢Pe 55 ^ 45 ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll A¡−hceL¡l£l ¢fa¡l A¡−hceL¡l£l j¡a¡l NZfÊS¡a¿»£ h¡wm¡−cn plL¡l HL¢V l¢Pe 30 ^ 25 HL¢V l¢Pe 30 ^ 25 R¢h A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l fl ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll R¢h ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll R¢h paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h h¢ql¡Nje J f¡p−f¡VÑ A¢dcçl A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l fl A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h fl paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h Affix the photograph Affix applicant’s Affix applicant’s −j¢ne ¢l−Xhm f¡p−f¡VÑ A¡−hce glj Father’s photograph Mother’s photograph here and attest on the Machine Readable Passport Application Form here and attest on the here and attest on the photo photo photo −Lhmj¡œ 15 hvp−ll e£−Q AfË¡çhuú A¡−hceL¡l£l −r−œ Ef−l¡š² R¢hàu fË−u¡Se z • A¡−hce fœ¢V f¨lZ Ll¡l f¨−hÑ Ae¤NÊqf§hÑL −no fªù¡u h¢ZÑa p¡d¡le ¢e−cÑne¡pj§q paLÑa¡l p¢qa f¡W Ll²ez Please read carefully the General Instructions at the last page before filling the form. • a¡lL¡ (*) ¢Q¢q²a œ²¢jL ew …−m¡ AhnÉ f¨lZ£uz Serial numbers marked with star (*) marks must be filled in. -

Psj'che. The" Cocoons'' Or •· Cases" of So~Ie

January 1900.] PSJ'CHE. 7 13 ( 7) Vertex not advanced in front of the eyes ; median carina of pronotnm sc;~rcely elevated. I.f ( 15) 13ody u~ually broad between the shoulder~; Yertex narrower or equally wide with one of the eyes; second femoral carinae more o r less flexuous. or undulate, or lobate, or clype:1tc, 1·cry rarely straight. Gen. f'aratdlix Hoi. 15 (14) Vertex strongly n:trrnwed in front, the front bonier nc:~rly o tw-half the breadth of an eye, or less; body usually prolong<tte; branches of frontal costa sub-parallel, closely approximate. Gen. Tclmald!ix g .. n. n. 16 (3) Ante rior femor:t abo\'e cli~tinctly ancl broadly ~ulc:1tc: pronotum in front produceJ more or less above the head, Yery frequently hooked, ;11:cuminate, or, to a certain extent, obtusely rounded angulate; antennae sixteen to twenty two articles. Subfamily n ,\TB ACHID I :-IAE Dol. 17 ( 1 8) Body strongly tumid; do rsum of the pronotum com·ex, lightly punc tate, lateral carinae in front of the !>houlders wanting. Gen. !'axilla Dol. 1 S ( •7) Body narrower; clorsu1n o! the pronotum, bet\Yeen the carina rather conC<II'e , conspersecl with m ore or less longitudinal wrinkles, lateral carin::~e in front <1f the shoulders present. Gen. Tclligidca Scudd. THE" COCOONS'' OR •· CASES" OF SO~IE I3liRRO\\'l;'\G CA TERPlLL\RS. BY CAROLINE G. SOULE, BROOKLINE, l\1,\SS. From much watching of pupating enough to give ample room for c;15es. caterpillars, e~pecially of such sphin Into each box 1 put a lan·a ready to gids aud ceratocampids as go into the pupate, and wandel ing in ::-e;1rch of a ground to pupate, 1 gradually came to suitalJ!e place. -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

Riwo Sangchö Sang Offering

Riwo Sangchö Sang Offering Om Svasti The practice of Riwo Sangchö, the Mengak, 'secret instruction' from Lhatsiin Namkha Jikme's "Rigdzin Sokdrup ". Making an auspicious fire in a clean vessel or burner, burn aromatic woods, resins, medicinal plants, the three white and three sweet substances, and all kinds of incense and powder- whatever you have available-and sprinkle it with pure water. Taking Refuge (3x) OÆ ÀÂ HÎÆ KHA NYAM SI SHYI KYAP KUN NYING PO CHO OÆ ÀÂ HÎÆ Heart-essence of all sources of refuge of samsara and nirvana, as vast as space, WANG DRAK RIG DZIN PADMA TÖ TRENG TSAL Powerful and wrathful Vidyadhara, Pema Thötreng Tsal; KHYE KUR NANG SI GYAL WE KYIL KHOR DZOG Within your body, all that appears and exists is the perfect Buddha mandala: ORO KUN SI IE DRAL CHIR KYAP SU CHI In order to liberate all beings from samsara, I take Refuge in you! Generating the awakened mind, the heart of Bodhicitta (3x) SANG CHOK YESHE Ö SAL THIG LEI SHYIR I generate the Awakened Mind of Bodhicitta, so that DRO KUN DRIB SUM DAK NE KU DANG SUNG The three obscurations of all beings may be purified in the Ground of the luminous tigle of supremely secret wisdom, and TUK KYI THIG LER LHUN DRUP NANG SHYII NGANG With the Four Visions spontaneously perfected in the tigle of the Wisdom Body, Speech, and Mind, SHYON NU BUM KUR DROL WAR SEM KYE DO May they be liberated into the youthful vase body! Seven Branch Offering SHI RIG MA CHO NYUK MAR CHAK TSAL SHYING To the primordial, unaltered nature of Rigpa, I pay homage! TING TA DRAL WE Ö SAL CHÖPA BUL The