The Recovery of the Local Economy in Northern Aleppo: Reality and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

Political Economy Report English F

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY And ITS SOCIAL RAMIFICATIONS IN THREE SYRIAN CITIES: TARTOUS, Qamishli and Azaz Economic developments and humanitarian aid throughout the years of the conflict, and their effect on the value chains of different products and their interrelation with economic, political and administrative factors. January 2021 P a g e | 4 KEY MESSAGES • The three studied cities are located in different areas of control: Tartous is under the existing Syrian authority, Azaz is within the “Euphrates Shield” areas controlled by Turkey and the armed “opposition” factions loyal to it, and most of Qamishli is under the authority of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” and the “Self-Administration” emanating from it. Each of these regions has its own characteristics in terms of the "political war economy". • After ten years of conflict, the political economy in Syria today differs significantly from its pre-conflict conditions due to specific mechanisms that resulted from the war, the actual division of the country, and unilateral measures (sanctions). • An economic and financial crisis had hit all regions of Syria in 2020, in line with the Lebanese crisis. This led to a significant collapse in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound and a significant increase in inflation. This crisis destabilized the networks of production and marketing of goods and services, within each area of control and between these areas, and then the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this deterioration. • This crisis affected the living conditions of the population. The monthly minimum survival expenditure basket (SMEB) defined by aid agencies for an individual amounted to 45 working days of salaries for an unskilled worker in Azaz, 37 days in Tartous and 22 days in Qamishli. -

The Syrian Crisis: an Analysis of Neighboring Countries' Stances

POLICY ANALYSIS The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Series: Policy Analysis Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. ____________________________ The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non-Arab researchers. Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies PO Box 10277 Street No. 826, Zone 66 Doha, Qatar Tel.: +974 44199777 | Fax: +974 44831651 www.dohainstitute.org Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Lebanese Position toward the Syrian Revolution 1 Factors behind the Lebanese stances 8 Internationally 14 Domestically 14 The Jordanian Stance 15 Regional and International Influences 18 The Syrian Revolution and the Arab Levant 22 NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES’ STANCES ON SYRIA Introduction The Arab Levant region has significant geopolitical importance in the global political map, particularly because of its diverse ethnic and religious identities and the complexity of its social and political structures. -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

S/2012/503 Consejo De Seguridad

Naciones Unidas S/2012/503 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 16 de octubre de 2012 Español Original: inglés Cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas Siguiendo instrucciones de mi Gobierno y en relación con mis cartas de fechas 16 a 20 y 23 a 25 de abril, 7, 11, 14 a 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 y 31 de mayo y 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25 y 27 de junio de 2012, tengo el honor de trasmitir adjunta una lista pormenorizada de las violaciones del cese de la violencia cometidas por grupos armados en Siria el 24 de junio de 2012 (véase el anexo). Agradecería que la presente carta y su anexo se distribuyeran como documento del Consejo de Seguridad. (Firmado) Bashar Ja’afari Embajador Representante Permanente 12-55140 (S) 241012 241012 *1255140* S/2012/503 Anexo de las cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas [Original: árabe] Sunday, 24 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 23 June 2012 at 2020 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in Rif Dimashq. 2. On 23 June 2012 at 2100 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement checkpoints in Shaffuniyah, Shumu' and Umara' in Duma, killing Private Muhammad al-Sa'dah and wounding three soldiers, including a first lieutenant. -

Cooperation on Turkey's Transboundary Waters

Cooperation on Turkey's transboundary waters Aysegül Kibaroglu Axel Klaphake Annika Kramer Waltina Scheumann Alexander Carius Status Report commissioned by the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety F+E Project No. 903 19 226 Oktober 2005 Imprint Authors: Aysegül Kibaroglu Axel Klaphake Annika Kramer Waltina Scheumann Alexander Carius Project management: Adelphi Research gGmbH Caspar-Theyß-Straße 14a D – 14193 Berlin Phone: +49-30-8900068-0 Fax: +49-30-8900068-10 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.adelphi-research.de Publisher: The German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety D – 11055 Berlin Phone: +49-01888-305-0 Fax: +49-01888-305 20 44 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bmu.de © Adelphi Research gGmbH and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, 2005 Cooperation on Turkey's transboundary waters i Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 1.1 Motive and main objectives ........................................................................................1 1.2 Structure of this report................................................................................................3 2 STRATEGIC ROLE OF WATER RESOURCES FOR THE TURKISH ECONOMY..........5 2.1 Climate and water resources......................................................................................5 2.2 Infrastructure development.........................................................................................7 -

The Kurdish Question in the Middle East

Strategic Sectors | Security & Politics The Kurdish Question in the Middle Panorama East: Regional Dynamics and Return to National Control Olivier Grojean its influence in Iran (via the PJAK), in Syria (via the Lecturer in Political Science PYD and its SDF, which now control numerous The European Centre for Sociology and Political Kurdish and Arab territories) and even in Iraq, near Science (CESSP), University of Paris I-Panthéon- Mont Qandil where it is based, but also in the Sorbonne and National Center for Scientific Research Maxmûr Kurdish refugee camp in Turkey and the (CNRS), Paris Yazidi regions of Sinjar. In sum, the past few dec- Strategic Sectors | Security & Politics ades have seen a rise in power of Kurdish political parties, which have managed to profoundly region- The past four decades have seen an increasing re- alize the Kurdish question by allying themselves with gionalization of the Kurdish question on the Middle regional or global powers. At once both the life- East scale. The Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq blood and consequence of this regionalization, the War (1980-1988), the 1991 Gulf War and its con- rivalry between the conservative, liberal pole em- sequences throughout the 1990s, US intervention bodied by Barzani’s PDK and the post-Marxist revo- in Iraq in 2003, the Syrian revolution and its repres- lutionary pole embodied by the PKK has led to sion as of 2011 and finally, the increasing power of greater interconnection of Kurdish issues in differ- 265 the Islamic State as of 2014 have been important ent countries. vectors for the expansion of Kurdish issues. -

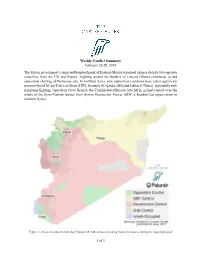

Weekly Conflict Summary

Weekly Conflict Summary February 22-28, 2018 The Syrian government’s siege and bombardment of Eastern Ghouta remained intense despite two separate ceasefires from the UN and Russia. Fighting around the borders of Eastern Ghouta continued, as did opposition shelling of Damascus city. In northern Syria, new opposition coalitions have taken significant territory from Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra), apparently with minimum fighting. Operation Olive Branch, the Turkish-led offensive into Afrin, gained control over the whole of the Syria-Turkish border from Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a Kurdish-led organization in northern Syria). Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 28, with arrows indicating fronts of advances during the reporting period 1 of 3 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 22-28, 2018 Eastern Ghouta Figure 2 - Situation in Eastern Ghouta by February 28 Strikes on opposition-held Eastern Ghouta continued throughout this reporting period. The situation in the besieged area is increasingly dire, with reports of a lack of access to basic nutrition, repeated attacks on hospitals, and mounting civilian casualties. On February 24, the UN Security Council adopted a resolution calling for a 30-day nation-wide ceasefire “without delay”. The resolution was adopted after repeated delays due to disagreements between the US and Russians on the text before the vote. The UN vote was intended to allow emergency aid deliveries to the region’s hardest-hit areas. Despite the resolution, fighting has continued throughout most of Syria, and has been particularly intense in Eastern Ghouta and in the northwestern Afrin region. -

IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet.Pdf

IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet www.stj-sy.com IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet 58 IDPs and Iraqi refugees’ camps are erected in northern rural Aleppo, controlled by the armed opposition groups, the majority of which are suffering from deplorable humanitarian conditions Page | 2 IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet www.stj-sy.com Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ recorded the presence of no less than 58 camps, random and regular, erected in northern rural Aleppo, which the armed Syrian opposition groups control. In these camps, there are about 37199 families, over 209 thousand persons, both displaced internally from different parts in Syria and Iraqi refugees. The camps spread in three main regions; Azaz, Jarabulus and Afrin. Of these camps, 41 are random, receiving no periodical aid, while residents are enduring humanitarian conditions that can be called the most overwhelming, compared to others, as they lack potable water and a sewage system, in addition to electricity and heating means. Camps Located in Jarabulus: In the region of Jarabulus, the Zaghroura camp is erected. It is a regular camp, constructed by the Turkish AFAD organization. It incubates 1754 families displaced from Homs province and needs heating services and leveling the roads between the tents. There are other 20 random camps, which receive no periodical aid. These camps are al- Mayadeen, Ayn al-Saada, al-Qadi, Ayn al-Baidah, al-Mattar al-Ziraai, Khalph al-Malaab, Madraset al-Ziraa, al-Jumaa, al-Halwaneh, al-Kno, al-Kahrbaa, Hansnah, Bu Kamal, Burqus, Abu Shihab, al-Malaab, al-Jabal and al-Amraneh.