European Commission 6 Framework Programme, Project No. 032055

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Social and Institutional Structures on Decision-Making And

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. The Effects of Social and Institutional Structures on Decision-Making and Benefit Distribution of Community Forestry in Nepal ___________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Lincoln University, New Zealand by Bhagwan Dutta Yadav ________________________________________ Lincoln University 2013 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forest Economics The effects of social and institutional structures on decision-making and benefit distribution of community forestry in Nepal by Bhagwan Dutta Yadav Participatory democracy has been an official part of Community Forestry (CF) since 1989 when the main policy document, the Master Plan for the Forestry Sector (MPFS), was introduced in Nepal. However, many problems related to benefit distribution from CF have emerged because of the way decision-making is influenced by the social and institutional structures present at the community level, particularly in terms of dominance by wealthy and caste elite and the inability of poor and disadvantaged households to participate fully in decisions. -

M4NH Interim Evaluation Report

MOVE 4 NEW HORIZONS A holistic educational programme for disadvantaged children in Nepal INTERIM EVALUATION REPORT Published in February 2010 byby:::: Swiss Academy for Development (SAD) Bözingenstrasse 71 CH-2502 Biel/Bienne Switzerland Phone +41 (0)32 344 30 50 Fax +41 (0)32 341 08 10 Web www.sad.ch www.sportanddev.org Email [email protected] Author: Valeria Kunz, Project Manager at the Swiss Academy for Development (SAD). Email: [email protected] The Swiss Academy for DevelDevelopmentopment (SAD) is a non-profit organisation located in Bienne, Switzerland. SAD makes a scientifically-grounded contribution to the creation and implementation of effective solutions and sustainable strategies in international development as well as in the area of social integration. Through applied social research, evaluations and pilot projects in Switzerland and abroad, SAD applies research evidence and practice-oriented knowledge to current topics and aims for a constructive exchange between theory and practice. Our focus areas are Intercultural Dialogue, Youth and Anomie, and Sport & Development. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................2 2 BACKGROUND................................................................................................3 2.1 Project activities..........................................................................................................3 2.2 Situation assessment ..................................................................................................4 -

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy Andactionplan2016-2025|Chitwan-Annapurnalandscape,Nepal

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy andActionPlan2016-2025|Chitwan-AnnapurnaLandscape,Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1- 4211567, 4211936 Fax: +977-1-4223868 Website: www.mfsc.gov.np Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Publisher: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Citation: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation 2015. Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025, Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Cover photo credits: Forest, River, Women in Community and Rhino © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Snow leopard © WWF Nepal/ DNPWC Rhododendron © WWF Nepal Back cover photo credits: Forest, Gharial, Peacock © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Red Panda © Kamal Thapa/ WWF Nepal Buckwheat fi eld in Ghami village, Mustang © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kapil Khanal Women in wetland © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kashish Das Shrestha © Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Acronyms and Abbreviations ACA Annapurna Conservation Area asl Above Sea Level BZ Buffer Zone BZUC Buffer Zone User Committee CA Conservation Area CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAPA Community Adaptation Plans for Action CBO Community Based Organization CBS -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 27: 67-125 (2004)

Realities and Images of Nepal’s Maoists after the Attack on Beni1 Kiyoko Ogura 1. The background to Maoist military attacks on district head- quarters “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” – Mao Tse-Tung’s slogan grabs the reader’s attention at the top of its website.2 As the slogan indicates, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) has been giving priority to strengthening and expanding its armed front since they started the People’s War on 13 February 1996. When they launched the People’s War by attacking some police posts in remote areas, they held only home-made guns and khukuris in their hands. Today they are equipped with more modern weapons such as AK-47s, 81-mm mortars, and LMGs (Light Machine Guns) purchased from abroad or looted from the security forces. The Maoists now are not merely strengthening their military actions, such as ambushing and raiding the security forces, but also murdering their political “enemies” and abducting civilians, using their guns to force them to participate in their political programmes. 1.1. The initial stages of the People’s War The Maoists developed their army step by step from 1996. The following paragraph outlines how they developed their army during the initial period of three years on the basis of an interview with a Central Committee member of the CPN (Maoist), who was in charge of Rolpa, Rukum, and Jajarkot districts (the Maoists’ base area since the beginning). It was given to Li Onesto, an American journalist from the Revolutionary Worker, in 1999 (Onesto 1999b). -

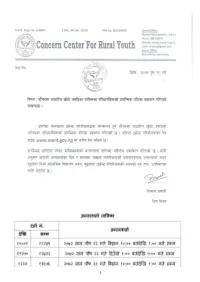

Peace Events in Sixteen Project Communities (28 Events Comprising Peace Rally, Cultural Progam,Speech Competition, Interaction, Sports and Revolving Fund)

ssi 2017 Peace Events in Sixteen Project Communities (28 events comprising Peace Rally, Cultural Progam,Speech Competition, Interaction, Sports and Revolving Fund) From Combatants to Peacemakers Program Submitted to THE DEMOCRACY AND GOVERNANCE OFFICE THE UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID) MISSION Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by Pro Public Kuleswore, Kathmandu P.O. Box: 14307 Telephone: +977-01-4283469 Email: [email protected] i Disclaimer: All these activities were made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Pro Public and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. ii Abbreviations CBO Community Based Organization CDO Chief District Officer C2P Combatants to Peacemakers CPN Communist Party of Nepal CSO Civil Society Organization DDC District Development Committee DE Dalit and Ethnic Communities DF Dialogue facilitation ECs Ex-Combatants FGD Focus Group Discussion GESI Gender and Social Inclusion GIZ Deutsche GesellschaftFür Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH KII Key Informant Interview LDO Local Development Office LPC Local Peace Committee NC Nepali Congress NPTF Nepal Peace Trust Fund PLA People Liberation Army Pro Public Forum for the Protection of Public Interest SDG Social Dialogue Group SM Social Mobilizer STPP Strengthening the Peace Process UCPN United Communist Party of Nepal UML United Marxist Leninist UNDP United Nations Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VDC Village Development Committee WCF Ward Citizen Forum iii Acknowledgement This report briefly summarizes the activity report of peace events organized by Pro Public under the 'Combatants to Peacemakers' Program (C2P) supported by United States Agency for International Development (USAID), during the period of September 2016 to May 2017. -

Collection and Conservation of Leguminous Crops and Their Wild Relatives in Cambodia, 2013

〔AREIPGR Vol. 30 : 109 ~ 143 ,2014〕 Original Paper Collection and Conservation of Leguminous Crops and Their Wild Relatives in Cambodia, 2013 Yu TAKAHASHI 1), 2), Uong PEOU 3), Seang LAY HENG 3), Ty CHANNA 3), Ouk MAKARA 3) and Norihiko TOMOOKA 1) 1) Genetic Resources Center, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Kannondai 2-1-2, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8602, Japan 2) Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 3) Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, National Road 3, Prateahlang, Dangkor, P.O Box 01, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Corresponding author : N. TOMOOKA (e-mail : [email protected]). Summary We have conducted a field survey on the leguminous plants in Cambodia from 18th to 27th November, 2013. A total of 74 accessions were collected, including Vigna minima (Roxb.) Ohwi & Ohashi, Vigna umbellata (Thunb.) Ohwi & Ohashi, Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek, Vigna reflexo-pilosa Hayata, Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp., Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Glycine max (L.) Merr.. The seeds had been conserved in the Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI) genebank, and the subset was transferred to the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (NIAS) genebank. We plan to multiply the seeds and evaluate their growth traits in NIAS, Japan. KEY WORDS : Cambodia, Legume, Vigna, Phaseolus vulgaris, Glycine max Introduction Improving the yield of food crop production is one of the most important and urgent challenges for human being. This challenge requires the genetic diversity of crop for developing new crop varieties with both stress tolerance and high yield performance. However, the genetic diversity of crop has been decreased since the advent of modern agriculture. -

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Chapter 3 Project Evaluation and Recommendations 3-1 Project Effect It is appropriate to implement the Project under Japan's Grant Aid Assistance, because the Project will have the following effects: (1) Direct Effects 1) Improvement of Educational Environment By replacing deteriorated classrooms, which are danger in structure, with rainwater leakage, and/or insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, with new ones of better quality, the Project will contribute to improving the education environment, which will be effective for improving internal efficiency. Furthermore, provision of toilets and water-supply facilities will greatly encourage the attendance of female teachers and students. Present(※) After Project Completion Usable classrooms in Target Districts 19,177 classrooms 21,707 classrooms Number of Students accommodated in the 709,410 students 835,820 students usable classrooms ※ Including the classrooms to be constructed under BPEP-II by July 2004 2) Improvement of Teacher Training Environment By constructing exclusive facilities for Resource Centres, the Project will contribute to activating teacher training and information-sharing, which will lead to improved quality of education. (2) Indirect Effects 1) Enhancement of Community Participation to Education Community participation in overall primary school management activities will be enhanced through participation in this construction project and by receiving guidance on various educational matters from the government. 91 3-2 Recommendations For the effective implementation of the project, it is recommended that HMG of Nepal take the following actions: 1) Coordination with other donors As and when necessary for the effective implementation of the Project, the DOE should ensure effective coordination with the CIP donors in terms of the CIP components including the allocation of target districts. -

Supplementary

Supplementary Table S1. Sample ID, Chinese names, English names, scientific names, moisture content, morphology, and sources of 23 legumes. Moisture Sample ID Chinese name English name Scientific name Morphology Source content 1 Chixiaodou Small adzuki bean Vigna umbellata 12.4 % Commercial product Vigna angularis (Willd.) Ohwi et 2 Chidou Adzuki bean 11.1 % Commercial product Ohashi 3 Quedandou Pinto bean Phaseolus vulgaris 13.2 % Commercial product 4 Jinsidou Red pinto bean Phaseolus vulgaris 10.9 % Commercial product 5 Naihuadou Milky flower bean Phaseolus vulgaris 13.3 % Commercial product 6 Yandou Stone bean Flemingia fluminalis C.B.Clarke 11.1 % Commercial product 7 Bai huayaodou Light speckled bean Phaseolus vulgaris 13.1 % Commercial product 8 Majiangdou Spotted cowpea Vigna unguiculata 11.2 % Commercial product 9 Hebaodou Large zebra bean Phaseolus coccineus Linn. 12.9 % Commercial product 10 Baibiandou White flat bean Dolicho lablabL. 11.4 % Commercial product 11 Huayaodou Pinto kidney bean Phaseolus vulgaris 12.6 % Commercial product 12 Hongyaodou Red kidney ˙˙˙Phaseolus vulgaris 11.4 % Commercial product 13 Baiyundou Large white kidney bean Phaseolus vulgaris Linn. 11.6 % Commercial product 14 Yuan banmadou Small round pinto bean Phaseolus vulgaris 10.4 % Commercial product 15 Banmadou Small zebra bean Phaseolus coccineus Linn. 9.9 % Commercial product Mucuna cochinchine-sis(Lour)Tang 16 Maodou Velvet bean 11.7 % Commercial product et Wang 17 Chandou Broad bean Vicia faba L. 11.3 % Commercial product 18 Baiyaodou White kidney bean Phaseolus vulgaris 13.3 % Commercial product 19 Zhudou Green aduzki bean Vigna umbellata 11.1 % Commercial product 20 Mei dou Black-eyed pea Vigna unguiculata 11.8 % Commercial product 21 Xiaobaidou Small white bean Phaseolus vulgaris L. -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Bajhang Bajura Doti Achham Kailali Seti, Bajura Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894).