Applied Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australasian Journal of Philosophy 1947–2016: a Retrospective Using Citation and Social Network Analyses

Global Intellectual History ISSN: 2380-1883 (Print) 2380-1891 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rgih20 Australasian Journal of Philosophy 1947–2016: a retrospective using citation and social network analyses Martin Davies & Angelito Calma To cite this article: Martin Davies & Angelito Calma (2018): Australasian Journal of Philosophy 1947–2016: a retrospective using citation and social network analyses, Global Intellectual History To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23801883.2018.1478233 Published online: 28 May 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rgih20 GLOBAL INTELLECTUAL HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/23801883.2018.1478233 Australasian Journal of Philosophy 1947–2016: a retrospective using citation and social network analyses Martin Davies a and Angelito Calma b aGraduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; bWilliams Centre for Learning Advancement, Faculty of Business and Economics, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In anticipation of the journal’s centenary in 2027 this paper provides Citation analysis; bibliometric a citation network analysis of all available citation and publication analysis; social network data of the Australasian Journal of Philosophy (1923–2017). A total analysis; philosophy; of 2,353 academic articles containing 21,772 references were Australasian Journal of Philosophy; Kumu collated and analyzed. This includes 175 articles that contained author-submitted keywords, 415 publisher-tagged keywords and 519 articles that had abstracts. Results initially focused on finding the most published authors, most cited articles and most cited authors within the journal, followed by most discussed topics and emerging patterns using keywords and abstracts. -

A Life of Thinking the Andersonian Tradition in Australian Philosophy a Chronological Bibliography

own. One of these, of the University Archive collections of Anderson material (2006) owes to the unstinting co-operation of of Archives staff: Julia Mant, Nyree Morrison, Tim Robinson and Anne Picot. I have further added material from other sources: bibliographical A Life of Thinking notes (most especially, James Franklin’s 2003 Corrupting the The Andersonian Tradition in Australian Philosophy Youth), internet searches, and compilations of Andersonian material such as may be found in Heraclitus, the pre-Heraclitus a chronological bibliography Libertarian Broadsheet, the post-Heraclitus Sydney Realist, and Mark Weblin’s JA and The Northern Line. The attempt to chronologically line up Anderson’s own work against the work of James Packer others showing some greater or lesser interest in it, seems to me a necessary move to contextualise not only Anderson himself, but Australian philosophy and politics in the twentieth century and beyond—and perhaps, more broadly still, a realist tradition that Australia now exports to the world. Introductory Note What are the origins and substance of this “realist tradition”? Perhaps the best summary of it is to be found in Anderson’s own The first comprehensive Anderson bibliography was the one reading, currently represented in the books in Anderson’s library constructed for Studies in Empirical Philosophy (1962). It listed as bequeathed to the University of Sydney. I supply an edited but Anderson’s published philsophical work and a fair representation unabridged version of the list of these books that appears on the of his published social criticism. In 1984 Geraldine Suter published John Anderson SETIS website, to follow the bibliography proper. -

Discrete and Continuous: a Fundamental Dichotomy in Mathematics

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 7 | Issue 2 July 2017 Discrete and Continuous: A Fundamental Dichotomy in Mathematics James Franklin University of New South Wales Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Other Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Franklin, J. "Discrete and Continuous: A Fundamental Dichotomy in Mathematics," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 7 Issue 2 (July 2017), pages 355-378. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.201702.18 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol7/iss2/18 ©2017 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Discrete and Continuous: A Fundamental Dichotomy in Mathematics James Franklin1 School of Mathematics & Statistics, University of New South Wales, Sydney, AUSTRALIA [email protected] Synopsis The distinction between the discrete and the continuous lies at the heart of mathematics. Discrete mathematics (arithmetic, algebra, combinatorics, graph theory, cryptography, logic) has a set of concepts, techniques, and application ar- eas largely distinct from continuous mathematics (traditional geometry, calculus, most of functional analysis, differential equations, topology). -

Bibliography and Further Reading

Herring: Medical Law and Ethics, 7th edition Bibliography and Further Reading Aasi, G.-H. (2003) ‘Islamic legal and ethical views on organ transplantation and donation’ Zygon 38: 725. Abdallah, H., Shenfield, F., and Latarche, E. (1998) ‘Statutory information for the children born of oocyte donation in the UK’ Human Reproduction 13: 1106. Abdallah, S., Daar, S., and Khitamy, A. (2001) ‘Islamic Bioethics’ Canadian Medical Association Journal 9: 164. Abortion Law Reform Association (1997) A Report on NHS Abortion Services (ALRA). Abortion Rights (2004) Eroding Women’s Rights to Abortion (Abortion Rights). Abortion Rights (2007) Campaign for a Modern Abortion Law Launched as Poll Confirms Overwhelming Public Support (Abortion Rights). Academy of Medical Sciences (2011) Animals Containing Human Material (Academy of Medical Sciences). ACC (2004) Annual Report (ACC). Ackernman, J. (1998) ‘Assisted suicide, terminal illness, severe disability, and the double standard’ in M. Battin, R. Rhodes, and A. Silvers (eds) Physician Assisted Suicide (Routledge). Action for ME (2005) The Times Reports on Biological Research (Action for ME).Adenitire, J. (2016) ‘A conscience-based human right to be ‘doctor death’’ Public Law 613. Ad Hoc Advisory Group on the Operation of NHS Research Ethics Committees (2005) Report (DoH). Adams, T., Budden, M., Hoare, C. et al (2004) ‘Lessons from the central Hampshire electronic health record pilot project: issues of data protection and consent’ British Medical Journal 328: 871. Admiral, P. (1996) ‘Voluntary euthanasia’ in S. McLean (ed.) Death Dying and the Law (Dartmouth). Adshead, G. (2003) ‘Commentary on Szasz’ Journal of Medical Ethics 29: 230. Advisory Group on the Ethics of Xenotransplantation (1996) Report (DoH). -

Papers in History and Methodology of Analytic Philosophy

Papers in History and Methodology of Analytic Philosophy Brian Weatherson March 5, 2014 Contents 1 What Good are Counterexamples? 1 2 Morality, Fiction and Possibility 20 3 David Lewis 46 4 Humean Supervenience 81 5 Lewis, Naturalness and Meaning 96 6 Centrality and Marginalisation 114 7 Keynes and Wittgenstein 128 8 Doing Philosophy With Words 144 9 In Defense of a Kripkean Dogma 152 Co-authored with Jonathan Ichikawa and Ishani Maitra Bibliography 161 What Good are Counterexamples? e following kind of scenario is familiar throughout analytic philosophy. A bold philosopher proposes that all Fs are Gs. Another philosopher proposes a particular case that is, intuitively, an F but not a G. If intuition is right, then the bold philosopher is mistaken. Alternatively, if the bold philosopher is right, then intuition is mistaken, and we have learned something from philosophy. Can this alternative ever be realised, and if so, is there a way to tell when it is? In this paper, I will argue that the answer to the rst question is yes, and that recognising the right answer to the second question should lead to a change in some of our philosophical practices. e problem is pressing because there is no agreement across the sub-disciplines of phi- losophy about what to do when theory and intuition clash. In epistemology, particularly in the theory of knowledge, and in parts of metaphysics, particularly in the theory of causation, it is almost universally assumed that intuition trumps theory. Shope’s e Analysis of Knowl- edge contains literally dozens of cases where an interesting account of knowledge was jettisoned because it clashed with intuition about a particular case. -

The Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy: Program History

The Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy: Program History 1960 FIRST COLLOQUIUM Wilfrid Sellars, "On Looking at Something and Seeing it" Ronald Hepburn, "God and Ambiguity" Comments: Dennis O'Brien Kurt Baier, "Itching and Scratching" Comments: David Falk/Bruce Aune Annette Baier, "Motives" Comments: Jerome Schneewind 1961 SECOND COLLOQUIUM W.D. Falk, "Hegel, Hare and the Existential Malady" Richard Cartwright, "Propositions" Comments: Ruth Barcan Marcus D.A.T. Casking, "Avowals" Comments: Martin Lean Zeno Vendler, "Consequences, Effects and Results" Comments: William Dray/Sylvan Bromberger PUBLISHED: Analytical Philosophy, First Series, R.J. Butler (ed.), Oxford, Blackwell's, 1962. 1962 THIRD COLLOQUIUM C.J. Warnock, "Truth" Arthur Prior, "Some Exercises in Epistemic Logic" Newton Garver, "Criteria" Comments: Carl Ginet/Paul Ziff Hector-Neri Castenada, "The Private Language Argument" Comments: Vere Chappell/James Thomson John Searle, "Meaning and Speech Acts" Comments: Paul Benacerraf/Zeno Vendler PUBLISHED: Knowledge and Experience, C.D. Rollins (ed.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 1964. 1963 FOURTH COLLOQUIUM Michael Scriven, "Insanity" Frederick Will, "The Preferability of Probable Beliefs" Norman Malcolm, "Criteria" Comments: Peter Geach/George Pitcher Terrence Penelhum, "Pleasure and Falsity" Comments: William Kennick/Arnold Isenberg 1964 FIFTH COLLOQUIUM Stephen Korner, "Some Remarks on Deductivism" J.J.C. Smart, "Nonsense" Joel Feinberg, "Causing Voluntary Actions" Comments: Keith Donnellan/Keith Lehrer Nicholas Rescher, "Evaluative Metaphysics" Comments: Lewis W. Beck/Thomas E. Patton Herbert Hochberg, "Qualities" Comments: Richard Severens/J.M. Shorter PUBLISHED: Metaphysics and Explanation, W.H. Capitan and D.D. Merrill (eds.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966. 1965 SIXTH COLLOQUIUM Patrick Nowell-Smith, "Acts and Locutions" George Nakhnikian, "St. Anselm's Four Ontological Arguments" Hilary Putnam, "Psychological Predicates" Comments: Bruce Aune/U.T. -

The Melbourne Spectrum

Chapter 7 The Melbourne Spectrum T IS an old saying that philosophy begins with a sense of wonder. That is a source of philosophy, but there is another one, the sense Ithat ‘that’s all bullshit (and I can explain why)’. Different philoso- phers draw on these sources in differing proportions. An uncritical sense of wonder leads one out of philosophy altogether, into the land of the fairies, to start angels from under stones, find morals at every turn and hug the rainforest. A philosopher near the other extreme — or one, like David Stove, actually occupying the extreme — will at least still be doing philosophy, but it will consist entirely of criticism of others. In the Australian intellectual tradition, the wonder/criticism mix varies not only according to individuals but according to cities. At least, it has since 1927, when John Anderson arrived in Australia and Sydney and Melbourne set off on different paths. Various writers, mainly from Melbourne, have discoursed at some length on the con- trasts between the two cities in their styles of thought, and with all due allowance made for the hot air factor, there is undoubtedly some distinct difference to be identified. Where Sydney intellectuals, fol- lowing Anderson, tend to be critical, pessimistic, classical and opposed to ‘meliorist’ schemes to improve society, Melbourne’s unctuous bien pensants are eager to ‘serve society’, meaning, to instruct the great and powerful how they ought to go about achieving Progress and the perfection of mankind.1 Manning Clark — and it is characteristic of 1 J. Docker, Australian Cultural Elites: Intellectual Traditions in Sydney and Melbourne (Sydney, 1974); V. -

Ji Richapd'sylvan WHAT IS WRONG with APPLIED ETHICS Richard

197d /> << Ji p. I Richapd'Sylvan WHAT IS WRONG WITH APPLIED ETHICS Richard Sylvan There is much that is wrong with and in applied ethics. Specifically, there are three comprehensive counts where things are wrong with the commodity concerned, applied ethics, that is with applied ethics so economically viewed.1 Namely on the following three counts: • extraneous, with the supply, delivery, consumption, and the like of applied ethics, AE. The category prominently includes the delivery of applied ethics: what is done, taught and learnt, by whom, and how qualified (e.g. whether taught by professionals, professional ethicists or philosophers in particular). That has tended to presume that the commodity itself is more or less in order, though the presumption lacks good pedigree, delivery of defective goods being almost as ubiquitous as business enterprise. The present focus is not however upon the delivery, or other features of the production and consumption, packaging and marketing of the goods, but on features of the commodity itself, applied ethics itself. Thus • intraneous counts, concerning the commodity itself, where a further two things are wrong: •• the applied idea, and ••• what the application is presumed to be made to, established - or, should it be, establishment - ethics. Because an implicit premiss in organising the Philosophy and Applied Ethics Re-examined1 Conference seems to have been that the issues to be addressed are predominantly extraneous, and because most of the papers actually relevant to the Conference topic appear to focus on extraneous issues, the present exercise, by contrast, concentrates upon intraneous problems, especially the third: radical deficiencies in what is supposed to be applied, prevailing ethics, and some extensive repairs thereto. -

A Critical Evaluation of Peter Singer's Ethics

A Critical Evaluation of Peter Singer’s Ethics By Tanuja Kalita Roll No. 08614103 Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Guwahati - 781039 India A Critical Evaluation of Peter Singer’s Ethics A thesis submitted to Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Tanuja Kalita Roll No. 08614103 Supervisor Dr V Prabhu Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Guwahati - 781039 India April 2013 TH-1184_08614103 Dedicated to My Parents, Father -in -law and Daughter i TH-1184_08614103 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Guwahati 781039 Assam, India Statement I hereby declare that this thesis, entitled A Critical Evaluation of Peter Singer’s Ethics , is the outcome of my own research work in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, India, which has been carried out under the supervision of Dr. V Prabhu in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences. IIT Guwahati April 2013 Tanuja Kalita ii TH-1184_08614103 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Guwahati 781039 Assam, India Certificate It is certified that the matter embodied in the thesis entitled A Critical Evaluation of Peter Singer’s Ethics , submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tanuja Kalita , a student of the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, India, has been carried out under my supervision. It is also certified that this work has not been submitted anywhere else for the award of a research degree. -

![Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9516/contemporary-moral-theories-introduction-to-contemporary-consequentialism-syllabus-kian-mintz-woo-2419516.webp)

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo] Course Information In this course, I will introduce you to some of the ways that consequentialist thinking leads to surprising or counterintuitive moral conclusions. This means that I will focus on issues which are controversial such as vegetarianism, charity, climate change and health-care. I have tried to select readings that are both contemporary and engaging. Hopefully, these readings will make you think a little differently or give you new ideas to consider or discuss. This course will take place in SR09.53 from 15.15-16.45. I have placed all of the readings for the term (although there might be slight changes), along with questions in green to help guide your reading. Some weeks have a recommended reading as well, which I think will help you to see how people have responded to the kinds of arguments in the required text. Please look over the descriptions and see which readings you are most interested in presenting for class for our first session on 10.03.2016. (Please tell me if you ever find a link that does not work or have any problems accessing content on this Moodle page.) I have a policy that cellphones are off in class; we will have a 5-10 minute break in the course and you can check messages only during the break. As a bonus, I have included at least one fun thing each week which relates to the theme of that week. Marking The course has three marked components: 1. -

Five Misguided Attempts to Defend Speciesism

1 Five Misguided Attempts to Defend Speciesism Bryan Ross Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science September 2020 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Bryan Ross to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Bryan Ross in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 3 Acknowledgments I want to thank my supervisors, Gerald Lang and Rob Lawlor, for their priceless philosophical guidance. I am grateful for the patience, promptness, and diligence with which they have read and commented on so many drafts of each chapter of this thesis. This thesis would not have been possible without them. Thank you very much to Jessica Isserow and Patrick Tomlin for giving up their time to be my examiners. I am also very thankful for the financial support received from the University of Leeds, for the first 3 years of my PhD. I am incredibly lucky to have met Adina Covaci, Alison Toop, Emily Paul, Gary Mullen, Marc Wilcock, and Will Gamester during my time at Leeds. I honestly do not think I could have done this without all of you. Finally, I am indebted to my family - my parents, John and Belinda; my sisters, Cathy and Johanna; my brother, Johnny; my wife’s family, John, Sean, and Chloe; and my wife, Lisa- Marie, whom the thesis is dedicated to. -

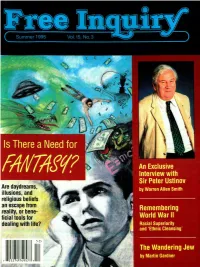

An Exclusive Interview with Sir Peter Ustinov

Is There a Need for An Exclusive FM'M? Interview with Sir Peter Ustinov Are daydreams, by Warren Allen Smith illusions, and religious beliefs an escape from Remembering reality, or bene- ficial tools for World War II dealing with life? Racial Superiority and `Ethnic Cleansing' The Wandering Jew by Martin Gardner Editor: Paul Kurtz SUMMER 1995, VOL. 15, NO. 3 ISSN 0272-0701 r- PreS1.re I Contents C Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Thomas W. Flynn, Gerald Larue, Gordon Stein 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Executive Editor: Timothy J. Madigan Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski 5 An Exclusive Interview with Contributing Editors: Robert S. Alley, Joe E. Barnhart, David Berman, Peter Ustinov Warren Allen Smith H. James Birx, Jo Ann Boydston, Bonnie Bullough, Paul Edwards, Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles 8 EDITORIALS W. Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Adolf Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Jean Kotkin, Thelma Agenda for the Humanist Movement in the Twenty-First Century, Paul Lavine, Tibor Machan, Ronald A. Lindsay, Michael Martin, Delos B. McKown, Lee Nisbet, John Novak, Kurtz / True Believers and Utter Madness, James A. Naught I Right to Skipp Porteous, Howard Radest, Robert Rimmer, Die: The Battle Is Joined, Ronald A. Lindsay Michael Rockier, Svetozar Stojanovic, Thomas Szasz, V. M. Tarkunde, Richard Taylor, Rob Tielman 15 Humanist Potpourri Warren Allen Smith Associate Editors: Molleen Matsumura, Lois Porter 19 Editorial Associates: REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II Doris Doyle, Thomas Franczyk, Roger Greeley, 19 Racial Superiority and `Ethnic Cleansing' Revisited Paul Kurtz James Martin-Diaz, Steven L. Mitchell, Warren Allen Smith 20 Why I Am Immune to Mysticism Paul A.