A Study of the Development of Mizo Language in Relation to Word Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Origin and Development of the Meitei Language

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Modern Education (IJMRME) ISSN (Online): 2454 - 6119 (www.rdmodernresearch.org) Volume II, Issue I, 2016 ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE MEITEI LANGUAGE Khongbantabam Naobi Devi Ph.D Scholar, Department of English, Ethiraj College for Women, Chennai, Tamilnadu Abstract: Meitei language is an Indo-Aryan language. The Indo- Aryans came to Manipur and settled in the Manipur from the 4th century B.C. onwards. The noted historian and scholar R.K. Jhalajit Singh present his views on the topic to Dr. Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, the great scholar and experts on language. He expressed as Meitei language may not belong to the Kuki- Chin sub-group of the Tibeto-Burman branch; but belongs to the Sino-Tibetan family of language. All the language that belongs to the Tibeto-Burman, a sub-branch of the Sino- Tibetan family of languages, is mono- syllabic. The Meiteis language is not a monosyllabic language; it is a polysyllabic language. In meiteis language, majority of words have more than one syllable. A language should be classified because of grammar. This is the universal principle accepted on all. A language cannot be classified according to vocabulary. If we begin to classify a language according to its vocabulary, the results will be incorrect. The first settlers of the Indo-Aryans in Manipur spoke Sanskrit. Later settlers spoke Prakrit. When Prakrit was removed as spoken language, they spoke Apabhransha.. The combination of Apabhransha and Mongoloid languages gave birth to the Manipuri language by about 1074 A.D. In the olden days of the Meitei language, which was formed by the interaction of Apabhransha and Mongoloid languages, the most important words were taken from Sanskrit. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

2020 Special Issue

Journal Home page : www.jeb.co.in « E-mail : [email protected] Original Research Journal of Environmental Biology TM p-ISSN: 0254-8704 e-ISSN: 2394-0379 JEB CODEN: JEBIDP DOI : http://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/4(SI)/MS_1903 Plagiarism Detector Grammarly Ichthyofauna of Dampa Tiger Reserve Rivers, Mizoram, North-Eastern India Lalramliana1*, M.C. Zirkunga1 and S. Lalronunga2 1Department of Zoology, Pachhunga University College, , Aizawl-796 001, India 2Systematics and Toxicology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Mizoram University, Aizawl – 796 004, India *Corresponding Author Email : [email protected] Paper received: 04.02.2020 Revised received: 03.07.2020 Accepted: 10.07.2020 Abstract Aim: The present study was undertaken to assess the fish biodiversity in buffer zone of rivers of the Dampa Tiger Reserve, Mizoram, India and to evaluate whether the protected river area provides some benefits to riverine fish biodiversity. Methodology: Surveys were conducted in different Rivers including the buffer zone of Dampa Tiger Reserve during the period of November, 2013 to May, 2014 and October, 2019. Fishes were caught using different fishing nets and gears. Collected fish specimens were identified to the lowest possible taxon using taxonomic keys. Specimens were deposited to the Pachhunga University College Museum of Fishes (PUCMF) and some specimens to Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) Kolkata. Shannon-Wiener diversity index was calculated. Results: A total of 50 species belonging to 6 orders, 18 families and 34 genera were collected. The order Cypriniformes dominated the collections comprising 50% of the total fish species collected. The survey resulted in the description of 2 new fishOnline species, viz. -

Volume III Issue II Dec2016

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies MZU JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURAL STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Volume III Issue 2 ISSN:2348-1188 Editor-in-Chief : Prof. Margaret L. Pachuau Editor : Dr. K.C. Lalthlamuani Editorial Board: Prof. Margaret Ch.Zama Prof. Sarangadhar Baral Dr. Lalrindiki T. Fanai Dr. Cherrie L. Chhangte Dr. Kristina Z. Zama Dr. Th. Dhanajit Singh Advisory Board: Prof.Jharna Sanyal,University of Calcutta Prof.Ranjit Devgoswami,Gauhati University Prof.Desmond Kharmawphlang,NEHU Shillong Prof.B.K.Danta,Tezpur University Prof.R.Thangvunga,Mizoram University Prof.R.L.Thanmawia, Mizoram University Published by the Department of English, Mizoram University. 1 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies 2 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies EDITORIAL It is with great pleasure that I write the editorial of this issue of MZU Journal of Literature and Culture Studies. Initially beginning with an annual publication, a new era unfolds with regards to the procedures and regulations incorporated in the present publication. The second volume to be published this year and within a short period of time, I am fortunate with the overwhelming response in the form of articles received. This issue covers various aspects of the political, social and cultural scenario of the North-East as well as various academic paradigms from across the country and abroad. Starting with The silenced Voices from the Northeast of India which shows women as the worst sufferers in any form of violence, female characters seeking survival are also depicted in Morrison’s, Deshpande’s and Arundhati Roy’s fictions. -

Languages and Peoples of the Eastern Himalayan Region (LPEHR)

Languages and Peoples of the Eastern Himalayan Region (LPEHR) Deictic motion in Hakhun Tangsa Krishna Boro Gauhati University ABSTRACT This paper provides a detailed description of how deictic motion events are encoded in a Tangsa variety called Hakhun, spoken in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam in India, and in Sagaing Region in Myanmar. Deictic motion events in Hakhun are encoded by a set of two motion verbs, their serial or versatile verb counterparts, and a set of two ventive particles. Impersonal deictic motion events are encoded by the motion verbs alone, which orient the motion with reference to a center of interest. Motion events with an SAP figure or ground are simultaneously encoded by the motion verbs and ventive particles. These motion events evoke two frames of reference: a home base and the speech-act location. The motion verbs anchor the motion with reference to the home base of the figure, and the ventives (or their absence) anchor the motion with reference to the location of the speaker, the addressee, or the speech-act. When the motion verbs are concatenated with other verbs, they specify motion associated with the action denoted by the other verb(s). KEYWORDS Hakhun, Tibeto-Burman, deictic motion, motion verbs, ventive This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics Vol 19(2) Languages and Peoples of the Eastern Himalayan Region: 9 29. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2020. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics Vol 19(2) Languages and Peoples of the Eastern Himalayan Region © CC by-nc-nd-4.0 2020 ISSN 1544-7502 Deictic motion in Hakhun Tangsa1 Krishna Boro Gauhati University 1 Introduction This paper describes how deictic motion events are encoded and contextually anchored in the speech situation in Hakhun, a variety of Tangsa or Tangshang (Ethnologue ISO 639-3 nst) spoken in the states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, India, and in Sagaing Region, Myanmar. -

The State and Identities in NE India

1 Working Paper no.79 EXPLAINING MANIPUR’S BREAKDOWN AND MANIPUR’S PEACE: THE STATE AND IDENTITIES IN NORTH EAST INDIA M. Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE February 2006 Copyright © M.Sajjad Hassan, 2006 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Development Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Programme Explaining Manipur’s Breakdown and Mizoram’s Peace: the State and Identities in North East India M.Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE Abstract Material from North East India provides clues to explain both state breakdown as well as its avoidance. They point to the particular historical trajectory of interaction of state-making leaders and other social forces, and the divergent authority structure that took shape, as underpinning this difference. In Manipur, where social forces retained their authority, the state’s autonomy was compromised. This affected its capacity, including that to resolve group conflicts. Here powerful social forces politicized their narrow identities to capture state power, leading to competitive mobilisation and conflicts. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

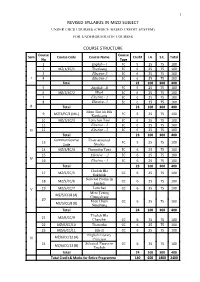

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

Eighth Legislative Assembly of Mizoram (Fourth Session)

1 EIGHTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MIZORAM (FOURTH SESSION) LIST OF BUSINESS FOR FIRST SITTING ON TUESDAY, THE 19th NOVEMBER, 2019 (Time 10:30 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. and 2:00 P.M. to 4:00 P.M.) OBITUARY 1. PU ZORAMTHANGA, hon. Chief Minister to make Obituary reference on the demise of Pu Thankima, former Member of Mizoram Legislative Assembly. QUESTIONS 2. Questions entered in separate list to be asked and oral answers given. ANNOUNCEMENT 3. THE SPEAKER to announce Panel of Chairmen. LAYING OF PAPERS 4. Dr. K. PACHHUNGA, to lay on the Table of the House a copy of Statement of Action Taken on the further recommendation of Committee on Estimates contained in the First Report of 2019 relating to State Investment Programme Management Implementation Unit (SIPMIU) under Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation Department Government of Mizoram. 5. Dr. ZR. THIAMSANGA, to lay on the Table of the House a a copy Statement of Actions Taken by the Government against further recommendations contained in the Third Report, 2019 of Subject Committee-III relating to HIV/AIDS under Health & Family Welfare Department. PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 6. THE SPEAKER to present to the House the Third Report of Business Advisory Committee. 7. PU LALDUHOMA to present to the House the following Reports of Public Accounts Committee : 2 i) First Report on the Report of Comptroller & Auditor General of India for the year 2011-12, 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15 and 2015-16 relating to Taxation Department. ii) Second Report on the Report of Comptroller & Auditor General of India for the year 2014-15 and 2015-16 relating to Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs Department. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

TDC Syllabus Under CBCS for Persian, Urdu, Bodo, Mizo, Nepali and Hmar

Proposed Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. (Honours) Persian 1 B.A. (Hons.): Persian is not merely a language but the life line of inter-disciplinary studies in the present global scenario as it is a fast growing subject being studied and offered as a major subject in the higher ranking educational institutions at world level. In view of it the proposed course is developed with the aims to equip the students with the linguistic, language and literary skills for meeting the growing demand of this discipline and promoting skill based education. The proposed course will facilitate self-discovery in the students and ensure their enthusiastic and effective participation in responding to the needs and challenges of society. The course is prepared with the objectives to enable students in developing skills and competencies needed for meeting the challenges being faced by our present society and requisite essential demand of harmony amongst human society as well and for his/her self-growth effectively. Therefore, this syllabus which can be opted by other Persian Departments of all Universities where teaching of Persian is being imparted is compatible and prepared keeping in mind the changing nature of the society, demand of the language skills to be carried with in the form of competencies by the students to understand and respond to the same efficiently and effectively. Teaching Method: The proposed course is aimed to inculcate and equip the students with three major components of Persian Language and Literature and Persianate culture which include the Indo-Persianate culture, the vital portion of our secular heritage.