Boso's- Lfe of Alexdnder 111

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte De Sordi with the Vicenza Mode

anticSwiss 28/09/2021 06:49:50 http://www.anticswiss.com Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi with the Vicenza mode FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 16° secolo - 1500 Ars Antiqua srl Milano Style: Altri stili +39 02 29529057 393664680856 Height:51cm Width:40.5cm Material:Olio su tela Price:3400€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: 16th century Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi with the model of the city of Vicenza Oil on oval canvas, 51 x 40.5 cm The oval canvas depicts a holy bishop, as indicated by the attributes of the miter on the head of the young man and the crosier held by angel behind him. The facial features reflect those of a beardless young man, with a full and jovial face, corresponding to a youthful depiction of the blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte (Cremona, c. 1125 - Vicenza, March 16, 1181). Another characteristic attribute is the model of the city of Vicenza that he holds in his hands, the one of which he became bishop in 1175. Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi lived at the time of the struggle undertaken by the emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1125-1190), against the Papacy and the Italian Municipalities. Giovanni was born in Cremona around 1125 from a family of noble origins; still at an early age he lost his father, his mother remarried the noble Adamo Cacciafronte, who loved him as his own son, giving him his name; he received religious and cultural training. At sixteen he entered the Abbey of San Lorenzo in Cremona as a Benedictine monk; over the years his qualities and virtues became more and more evident, and he won the sympathies of his superiors and confreres. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14770-6 — Turin and the British in the Age of the Grand Tour Edited by Paola Bianchi , Karin E. Wolfe Frontmatter More Information i Turin and the British in the Age of the Grand Tour h e Duchy of Savoy i rst claimed royal status in the seventeenth century, but only in 1713 was Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy (1666– 1732), crowned King of Sicily. h e events of the Peace of Utrecht (1713) sanc- tioned the decades- long project the Duchy had pursued through the con- voluted maze of political relationships between foreign powers. Of these, the British Kingdom was one of their most assiduous advocates, because of complementary dynastic, political, cultural and commercial interests. A notable stream of British diplomats and visitors to the Sabaudian capital engaged in an extraordinary and reciprocal exchange with the Turinese during this fertile period. h e l ow of travellers, a number of whom were British emissaries and envoys posted to the court, coincided, in part, with the itineraries of the international Grand Tour which transformed the capital into a gateway to Italy, resulting in a conl agration of cultural cosmopolitanism in early modern Europe. PAOLA BIANCHI teaches Early Modern History at the Universit à della Valle d’Aosta. She has researched and written on the journeys of various English travellers who came to Italy in the eighteenth century to be pre- sented at the Savoy court and to be part of Piedmont society. Her pub- lications include Onore e mestiere. Le riforme militari nel Piemonte del Settecento (2002); Cuneo in et à moderna. -

Manufacturing Middle Ages

Manufacturing Middle Ages Entangled History of Medievalism in Nineteenth-Century Europe Edited by Patrick J. Geary and Gábor Klaniczay LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24486-3 CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ xiii Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 PART ONE MEDIEVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY HISTORIOGRAPHY National Origin Narratives in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy ..... 13 Walter Pohl The Uses and Abuses of the Barbarian Invasions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries ......................................................................... 51 Ian N. Wood Oehlenschlaeger and Ibsen: National Revival in Drama and History in Denmark and Norway c. 1800–1860 ................................. 71 Sverre Bagge Romantic Historiography as a Sociology of Liberty: Joachim Lelewel and His Contemporaries ......................................... 89 Maciej Janowski PART TWO MEDIEVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARCHITECTURE The Roots of Medievalism in North-West Europe: National Romanticism, Architecture, Literature .............................. 111 David M. Wilson Medieval and Neo-Medieval Buildings in Scandinavia ....................... 139 Anders Andrén © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24486-3 vi contents Restoration as an Expression -

Press Release WILLIAM KENTRIDGE Preparing the Flute

Press release WILLIAM KENTRIDGE Preparing the Flute Opening Wednesday 16 November 2005, 5.00 pm – 9.00 pm, Galleria Lia Rumma Naples, Via Vannella Gaetani, 12 Tel.+39.081.7643619, Fax+39.081.7644213 e-mail [email protected] –web: www.gallerialiarumma.it Gallery opening times: from Tuesday to Friday from 4.30 pm to 7.30 pm – on other days by appointment During 2005, William Kentridge was responsible for the sets and the direction of The Magic Flute by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart for the opening of the new season of Brussels La Monnaie/De Munt Opera House, as part of an initiative promoted by the same theatre with Foundation of the San Carlo Opera House in Naples, the Lille Opera House and the Theatre of Caen. The project to be shown at the Lia Rumma Gallery in Naples is entitled Preparing the Flute and presents a reduced scale interior of a theatre which refers to the set design adopted in Brussels. The structure has a series of five progressive wings which mark out the perspective of the space and act as a frame for the video projected onto the end wall. At the same time other animated images, these also drawn with white lines onto a black background are projected frontally using the lateral wings as screens. The video and the drawings on display in the exhibition show landscapes and figures that allude, often in ironical fashion, to the events and characters from Mozart’s opera. In this way, the themes which are already present in other of Kentridge’s works – such as the caged lion, the metamorphosis whereby objects are transformed into animals, the broken lines that become brightly lit paths.. -

History Italy (18151871) and Germany (18151890) 2Nd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HISTORY ITALY (18151871) AND GERMANY (18151890) 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Wells | 9781316503638 | | | | | History Italy (18151871) and Germany (18151890) 2nd edition PDF Book This is a good introduction, as it shows a clear grasp of the topic, and sets out a logical plan that is clearly focused on the demands of the question. Activities throughout the chapters to encourage an exploratory and inquiring approach to historical learning. Jacqueline Paris. In , Italy forced Albania to become a de facto protectorate. Written by an experienced, practising IB English teacher, it covers key concepts in language and literature studies in a lively and engaging way suited to IB students aged 16— The Fascist regime engaged in interventionist foreign policy in Europe. Would you like to change to the site? Bosworth says of his foreign policy that Crispi:. He wanted to re-establish links with the papacy and was hostile to Garibaldi. Assessment Italy had become one of the great powers — it had acquired colonies; it had important allies; it was deeply involved in the diplomatic life of Europe. You are currently using the site but have requested a page in the site. However, there were some signs that Italy was developing a greater national identity. The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western Mediterranean sea. Retrieved 21 March Ma per me ce la stiamo cavando bene". Urbano Rattazzi —73 : Rattazzi was a lawyer from Piedmont. PL E Silvio writes: Italy was deeply divided by This situation was shaken in , when the French Army of Italy under Napoleon invaded Italy, with the aims of forcing the First Coalition to abandon Sardinia where they had created an anti-revolutionary puppet-ruler and forcing Austria to withdraw from Italy. -

The History of Painting in Italy, Vol. V

The History Of Painting In Italy, Vol. V By Luigi Antonio Lanzi HISTORY OF PAINTING IN UPPER ITALY. BOOK III. BOLOGNESE SCHOOL. During the progress of the present work, it has been observed that the fame of the art, in common with that of letters and of arms, has been transferred from place to place; and that wherever it fixed its seat, its influence tended to the perfection of some branch of painting, which by preceding artists had been less studied, or less understood. Towards the close of the sixteenth century, indeed, there seemed not to be left in nature, any kind of beauty, in its outward forms or aspect, that had not been admired and represented by some great master; insomuch that the artist, however ambitious, was compelled, as an imitator of nature, to become, likewise, an imitator of the best masters; while the discovery of new styles depended upon a more or less skilful combination of the old. Thus the sole career that remained open for the display of human genius was that of imitation; as it appeared impossible to design figures more masterly than those of Bonarruoti or Da Vinci, to express them with more grace than Raffaello, with more animated colours than those of Titian, with more lively motions than those of Tintoretto, or to give them a richer drapery and ornaments than Paul Veronese; to present them to the eye at every degree of distance, and in perspective, with more art, more fulness, and more enchanting power than fell to the genius of Coreggio. Accordingly the path of imitation was at that time pursued by every school, though with very little method. -

Emperor Submitted to His Rebellious Subjects

Edinburgh Research Explorer When the emperor submitted to his rebellious subjects Citation for published version: Raccagni, G 2016, 'When the emperor submitted to his rebellious subjects: A neglected and innovative legal account of the 1183-Peace of Constance', English Historical Review, vol. 131, no. 550, pp. 519-39. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cew173 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/ehr/cew173 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: English Historical Review Publisher Rights Statement: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in The English Historical Review following peer review. The version of record [Gianluca Raccagni, When the Emperor Submitted to his Rebellious Subjects: A Neglected and Innovative Legal Account of the Peace of Constance, 1183 , The English Historical Review, Volume 131, Issue 550, June 2016, Pages 519–539,] is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cew173 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. -

Building in Early Medieval Rome, 500-1000 AD

BUILDING IN EARLY MEDIEVAL ROME, 500 - 1000 AD Robert Coates-Stephens PhD, Archaeology Institute of Archaeology, University College London ProQuest Number: 10017236 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10017236 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The thesis concerns the organisation and typology of building construction in Rome during the period 500 - 1000 AD. Part 1 - the organisation - contains three chapters on: ( 1) the finance and administration of building; ( 2 ) the materials of construction; and (3) the workforce (including here architects and architectural tracts). Part 2 - the typology - again contains three chapters on: ( 1) ecclesiastical architecture; ( 2 ) fortifications and aqueducts; and (3) domestic architecture. Using textual sources from the period (papal registers, property deeds, technical tracts and historical works), archaeological data from the Renaissance to the present day, and much new archaeological survey-work carried out in Rome and the surrounding country, I have outlined a new model for the development of architecture in the period. This emphasises the periods directly preceding and succeeding the age of the so-called "Carolingian Renaissance", pointing out new evidence for the architectural activity in these supposed dark ages. -

Andrea Bruno at the Velasca Tower

Milan, 9 May 2016 Starting today, the Velasca Tower will host an exhibition dedicated to an Italian master architect PROGETTARE L’ESISTENTE (DESIGNING THE EXISTING) ANDREA BRUNO AT THE VELASCA TOWER At the Velasca Tower, an exhibition of the architect Andrea Bruno expands on the themes of recovery and conservation A tribute to the architect Andrea Bruno before his departure for Paris where he will be awarded an honorary degree by the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers on 13 May Until 5 July, the Velasca Tower will host a retrospective exhibition dedicated to Andrea Bruno, an Italian mater architect who has linked his name to the design of museums and the ingenious conversion of historic buildings. For Andrea Bruno, transformation is “the only way to guarantee the preservation of memories through architecture”. The Velasca Tower, which has always represented the perfect synthesis of tradition and innovation, is thus the ideal location to display some of the main projects by the architect Andrea Bruno. During his professional career, Bruno has found the right balance between historic value and functionality, highlighting how the restoration of architectural icons can still be an opportunity for functional and economic historical enhancement. On display are 16 models, photographs, original sketches and technical drawings of some of the many projects realised from the 60s up until today, through which it is possible to understand the profound meaning of Designing the Existing for Bruno. An approach that starts with the identification of the correct use for the “existing” in order to enhance the same through innovative and always original design solutions that ensure its conservation over time. -

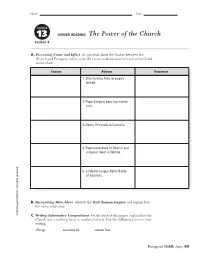

GUIDED READING the Power of the Church Section 4

wh10a-IDR-0313_P4 11/24/2003 4:05 PM Page 69 Name Date CHAPTER 13 GUIDED READING The Power of the Church Section 4 A. Perceiving Cause and Effect As you read about the clashes between the Church and European rulers, note the causes and outcomes of each action listed in the chart. Causes Actions Outcomes 1. Otto invades Italy on pope’s behalf. 2. Pope Gregory bans lay investi- ture. 3. Henry IV travels to Canossa. 4. Representatives of Church and emperor meet in Worms. 5. Lombard League fights Battle of Legnano. B. Recognizing Main Ideas Identify the Holy Roman Empire and explain how the name originated. cDougal Littell Inc. All rights reserved. ©M C. Writing Informative Compositions On the back of this paper, explain how the Church was a unifying force in medieval society. Use the following terms in your writing. clergy sacrament canon law European Middle Ages 69 wh10a-IDR-0313_P7 11/24/2003 4:06 PM Page 72 Name Date CHAPTER GEOGRAPHY APPLICATION: PLACE 13 Feudal Europe’s Religious Influences Section 4 Directions: Read the paragraphs below and study the map carefully. Then answer the questions that follow. he influence of the Latin Church—the Roman as did that of Hungary around 986. Large sections TCatholic Church—grew in western Europe of Scandinavia adopted the Latin Church by 1000. after 800. By 1000, at the end of the age of inva- In the fifth century, Ireland became the “island of sions, the Church’s vision of a spiritual kingdom in saints.” Then, between 500 and 900, Ireland helped feudal Europe was nearly realized. -

Wielding the Temporal Sword

WIELDING THE TEMPORAL SWORD AN ANALYSIS OF THE CREATION OF VATICAN CITY STATE IN RELATION TO THE CATHOLIC PERSPECTIVE ON STATEHOOD AND CATHOLIC DOCTRINE ON THE RELATION BETWEEN CHURCH AND STATE Master Thesis Political Theory Guido As August 15th 2016 Supervisor: Prof. dr. M.L.J. Wissenburg Abstract The Lateran Treaty of 1929 between Italy and the Roman Catholic Church constitutes the creation of Vatican City State. This thesis gives an account of the negotiations leading up to the signing of the Treaty. The creation of the City State draws our attention to two specific concepts: statehood and the separation of Church and state. The Catholic perspective on these concepts is presented and compared to other dominant theories of the concepts The Catholic perception of statehood in the early 20th century was based on the work of Fr. Taparelli, a Jesuit scholar who was heavily inspired by Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). The thesis concludes that there is a discrepancy between this theoretical conception of statehood, and the creation of Vatican City State. This can be explained by the fact that obtaining statehood was instrumental to the Holy See’s ambition of becoming sovereign. Catholic doctrine on the relation between Church and state has always rejected the idea of a full separation. Papal teachings have traditionally promoted a differentiation between a spiritual and temporal sphere of power, each supreme in its own domain, but cooperating in harmony. Depending on one´s interpretation, the creation of Vatican City is in line with this doctrine. Key words: Lateran Treaty, Vatican City State, separation of Church and State, statehood, sovereignty 2 Contents Chapter 1. -

Monarchs Retired from Business

MONAECHS RETIRED PROM BUSINESS. '^^<^<^<X (0)F S WE 32) IS W 3320S MONARCHS RETIRED FROM BUSINESS. BY DR. DORAN, AUTHOR OP ' KNIGHTS AND THEIR DATS,' ' QUEENS OP ENGLAND OF THE HOUSE OF HANOVEB," ' HABITS AND MEN, 'TABLE TEAITS AND SOMETHING ON THEM.' IN TWO VOLUMES. VOLUME II. ' I've thought, at gentle and ungentle hour, Of many an act and giant-shape of power, Of the old Kings with high-exacting looks, Sceptred and globed." LEIGH HUNT. LONDON : RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET, ^jluiilisfjer in tiinarg t0 |^er fHajrstg. 1857. [The right of Translation is reserved^] PRINTED BY JOHN EDWABD TAYLOR, LITTLE QUEEN STEEET, LINCOLN'S INN FIELDS. CONTENTS OP THE SECOND VOLUME. PAGE INCIDENTS IN THE LIYES OF RETIRED MONAECHS, DOWN TO THE DEATH OF VALERIAN 1 DIOCLETIAN 16 MAXIMIAN TO ROMULUS AUGUSTUS 30 3Kje Eastern Empire. GRAVE OB CLOISTER 46 THE BYZANTINE C^SARS OF THE ICONOCLASTIC PERIOD . 59 THE BASILIAN DYNASTY. MONARCHS AMONG THE MONKS . 77 THE COMNENI. MORE TENANTS FOR STUDION 88 THE BALDWINS 96 THE MOST CHRISTIAN KING, MONK ANTONY 102 THE PAPAL DYNASTY 112 ----- :*=== THE THREE Pn 136 Russia. THE CZARS 168 IVAN VI 175 Sardinia. VICTOR AMADEUS 1 195 THREE CHOWNLESS KINGS , . 205 VI CONTENTS. PAGE EEIC IX. CHBISTIAX II.............. 218 SWEDEN ................... 233 THE STOBY OF EEIC XIV............. 240 CHEISTINA .................. 255 GUSTAVUS IV............... 308 Spam. PHILIP V................... 330 CHABLES IV.................. 334 Portugal. SANCHO II................... 350 ALPHONSO VI.................. 354 Curfeeg. THE Two BAJAZETS ............... 373 Conclusion .............. 394 MONARCHS RETIRED FROM BUSINESS, FROM JULIUS TO YALERIAN. " Here a vain man his sceptre breaks, The next a broken sceptre takes, And warriors win and lose ; This rolling world will never stand, Plunder'd and snatch'd from hand to hand, As power decays or grows." ISAAC WATTS.