Department of History University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire Camp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsin College Id Camp #2 July 10Th, 2021 Schedule

WISCONSIN COLLEGE ID CAMP #2 JULY 10TH, 2021 SCHEDULE 9:30 am – 9:55 am: Camp Registration 10:00 am – 11:45 am: Training Session 12:00 pm – 12:40 pm: Lunch (Please bring your own Lunch) 12:45 pm – 1:10 pm: Paula’s Presentation 1:15 pm – 2:30 pm: Group A: Athletic Facility Tour Group B: 11 vs. 11 Match 2:45 pm – 4:00 pm: Group B: Athletic Facility Tour Group A: 11 vs. 11 Match 4:00 pm: Camp Concludes WISCONSIN COLLEGE ID CAMP #2 MASTER Last Name First Name Grad Year Position: Training Group Adamski Kailey 2022 Goalkeeper Erin Scott A Awe Delaney 2025 Forward Tim Rosenfeld B Baczek Grace 2023 Defense Paula Wilkins A Bekx Sarah 2023 Defense Tim Rosenfeld B Bever Sonoma 2025 Forward Tim Rosenfeld B Beyersdorf Kamryn 2025 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld B Breunig McKenna 2025 Midfield Marisa Kresge B Brown Brooke 2023 Midfield Paula Wilkins A Chase Nicole 2025 Defense Tim Rosenfeld B Ciantar Elise 2022 Forward Marisa Kresge B Davis Abigail 2024 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld B Denk Sarah 2024 Defense Paula Wilkins A Desmarais Abigail 2023 Midfield Marisa Kresge A Duffy Eily 2025 Midfield Marisa Kresge B Dykstra Grace 2025 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld B Fredenhagen Alexia 2023 Defense Marisa Kresge A Gichner Danielle 2024 Defense Paula Wilkins A Guenther Eleanor 2026 Defense Tim Rosenfeld B Last Name First Name Grad Yr. Position: Training Group Hernandez ‐ Rahim Gabriella 2023 Forward Marisa Kresge A Hildebrand Peyton 2022 Defense Paula Wilkins A Hill Kennedy 2022 Defense Paula Wilkins A Hill Lauren 2025 Defense Paula Wilkins A Hoffmann Sophia 2022 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld -

Talk Like a Badger

Talk Like a Badger Student Center A section of the UW’s website, which allows students to schedule If you feel like your student is speaking an entirely different language, classes, check grades and graduation requirements, and pay tuition bills. this UW vocabulary list can help. TA. Shout-Outs. ASM. Langdon. Huh? Center for Leadership and Involvement The CFLI offers students a variety of leadership programs, while also When your student first starts sprinkling these terms — and more encouraging them to get involved in the campus community through — during conversations, you may find yourself in need of a translator. student organizations, intramural sports, and volunteer activities. Along with other aspects of his or her new environment, your student has been learning a new vocabulary. And while it’s become second nature to your student, as a parent, you might need a little help. Student Traditions The Parent Program asked some students to make a list of com- Homecoming monly used words and phrases, and provide definitions. Now it’s time A week of events — typically in October — that celebrates everything for you to go into study mode and review the list below. Badger. A Homecoming Committee, with support from the Wisconsin Before you know it, you’ll be talking Badger, too. Alumni Association, coordinates special events that honor UW tradi- tions; any proceeds from events benefit the Dean of Students Crisis Academically Speaking Loan fund, which helps students with financial burdens. The week is capped off by a parade down State Street on Friday afternoon, with Schools and colleges the Homecoming football game on Saturday. -

Personnel Matters an Administrator’S Extended Leave Has UW’S Policies Under Scrutiny

DISPATCHES Personnel Matters An administrator’s extended leave has UW’s policies under scrutiny. Questions about a UW-Madison for an explanation. While administrative leave until the administrator’s extended leave expressing confidence that all investigation is complete. flared tensions between the university policies were fol- Coming in the middle of university and some state law- lowed in granting Barrows Wisconsin’s biennial state budget makers this summer, sparking leave, Wiley (who is Barrows’ deliberations, the case may have an investigation that may supervisor) agreed to appoint several lasting effects on the uni- affect how the university han- an independent investigator to versity. Lawmakers voted to cut dles personnel decisions. determine whether any of the UW-Madison’s budget by an The controversy involves a actions he or Barrows took additional $1 million because of leave of absence taken by Paul were inappropriate. Susan the controversy, and the Joint Barrows, the former vice chan- Steingass, a Madison attorney Legislative Audit Committee has cellor for student affairs. The and former Dane County Circuit now requested information on leave, for which Barrows used Court judge who teaches in the paid leaves and backup appoint- accumulated vacation and sick Law School, was designated to ments throughout the UW Sys- days, came after he acknowl- explore the matter and is tem to help it decide whether to edged a consensual relationship expected to report her findings launch a System-wide audit of with an adult graduate student. this fall to UW System President personnel practices. While not a violation of univer- Kevin Reilly and UW-Madison The UW Board of Regents sity policy, the revelation raised Provost Peter Spear. -

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Agenda

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Office of the Secretary 1860 Van Hise Hall Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608)262-2324 October 29 2003 TO: Each Regent FROM: Judith A. Temby RE: Agendas and supporting documents for meetings of the Board and Committees to be held Thursday at The Lowell Center, 610 Langdon St. and Friday at 1820 Van Hise Hall, 1220 Linden St., Madison on November 6 and 7, 2003. Thursday, November 6, 2003 10:00 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. - Regent Study Groups • Revenue Authority and Other Opportunities, Lowell Center, Lower Lounge • Achieving Operating Efficiencies, Lowell Center, room B1A • Re-Defining Educational Quality, Lowell Center room B1B • The Research and Public Service Mission, State Capitol • Our Partnership with the State, Lowell Center, room 118 12:30 - 1:00 p.m. - Lunch, Lowell Center, Lower Level Dinning room 1:00 p.m. - Board of Regents Meeting on UW System and Wisconsin Technical College System Credit Transfer Lowell Center, room B1A/B1B 2:00 p.m. – Committee meetings: Education Committee Lowell Center, room 118 Business and Finance Committee Lowell Center, room B1A/B1B Physical Planning and Funding Committee Lowell Center, Lower Lounge 3:30 p.m. - Public Investment Forum Lowell Center, room B1A/B1B Friday, November 7, 2003 9:00 a.m. - Board of Regents 1820 Van Hise Hall Persons wishing to comment on specific agenda items may request permission to speak at Regent Committee meetings. Requests to speak at the full Board meeting are granted only on a selective basis. Requests to speak should be made in advance of the meeting and should be communicated to the Secretary of the Board at the above address. -

Cultural Landscape Inventory December 2005 (Revisions Aug 2011)

Camp Randall Memorial Park Cultural Landscape Inventory December 2005 (Revisions Aug 2011) Quinn Evans|Architects University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Landscape Architecture, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences Division of Facilities Planning and Management ©2011, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System University of Wisconsin-Madison Cultural Landscape Inventory DEFINITIONS What is a “cultural landscape”? The following document is based on concepts and techniques developed by the National Park Service (NPS). The NPS has produced a series of manuals for identifying, describing, and maintaining culturally significant landscapes within the national park system.1 The National Park Service defines a cultural landscape as a geographic area, including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein[,] associated with a historic event, activity, or person, or [one] that exhibits other cultural or aesthetic values.2 In 1925, geographer Carl Sauer (1889-1975) summarized the process that creates cultural landscapes: “Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape the result.” 3 Similarly, the writer J. B. Jackson (1909-1996) looked upon the landscape as a composition of spaces made or modified by humans “to serve as infrastructure or background for our collective existence.”4 What is a “cultural landscape inventory”? 5 This cultural landscape inventory for Camp Randall Memorial Park is one of eight such studies completed as part of the UW-Madison Cultural Landscape Resource Plan. Each inventory defines the boundaries of a distinct cultural landscape on campus, summarizes its history, describes its current condition, and makes recommendations about its treatment. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (January 1992) Wisconsin Word Processing Format (Approved 1/92) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of Interior National Park Service MOV 14 ?^0 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900A). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_______________________________________________ historic name Boscobel Grand Army of the Republic Hall____________________________________ other names/site number First Baptist Church__________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 102 Mary Street N/A not for publication city or town Boscobel N/A vicinity state Wisconsin code WI county Grant code 043 zip code 53805 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

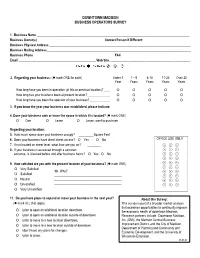

Downtown Madison, Wisconsin, Business Operators Survey

DOWNTOWN MADISON BUSINESS OPERATORS SURVEY 1. Business Name _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Business Owner(s) _________________________________________Contact Person if Different:_____________________________ Business Physical Address ______________________________________________________________________________________ Business Mailing Address________________________________________________________________________________________ Business Phone _________________________________________________ FAX __________________________________________ Email _______________________________________________ Web Site _________________________________________________ 2. Regarding your business: (l mark ONE for each) Under 1 1 – 5 610 1120 Over 20 Year Years Years Years Years How long have you been in operation (at this or previous location)? O O O O O How long has your business been at present location? O O O O O How long have you been the operator of your business? O O O O O 3. If you know the year your business was established, please indicate:_____________ 4. Does your business own or lease the space in which it is located? (l mark ONE) O Own O Lease O Lease, want to purchase Regarding your location: 5. How much space does your business occupy? _________Square Feet 6. Does your business have direct street access? O Yes O No OFFICE USE ONLY 7. If not located on street level, what floor are you on? ________ 0 0 0 8. If your business is accessed through a common 1 1 1 entrance, is it locked before and after business hours? O Yes O No 2 2 2 3 3 3 9. How satisfied are you with the present location of your business? (l mark ONE) 4 4 4 O Very Satisfied 5 5 5 10. Why? 6 6 6 O Satisfied _________________________________________ 7 7 7 O Neutral _________________________________________ 8 8 8 O Unsatisfied _________________________________________ 9 9 9 O Very Unsatisfied _________________________________________ 11. -

952.854.3100 [email protected] © Campus Media Group 2015 Sponsorship Opportunities Homecoming at UW-Madison

952.854.3100 [email protected] © Campus Media Group 2015 Sponsorship Opportunities Homecoming at UW-Madison Why Sponsor? Campus Media Group is proud to be a preferred partner of sponsorship sales for all UW- Homecoming Events in 2016. Connecting to the Badger community is a powerful step, providing value and awareness of your business. UW-Madison Homecoming strives to bring together thousands of students, staff, faculty, alumni and community members to participate in a variety of activities around the UW campus. Support of University of Wisconsin Homecoming will provide your business access to thousands of students, alumni and community members who are interested in your products/services. By the numbers... Sponsorship Levels Social Media reach: We invite you to take advantage of this o Twitter: 2,330 followers exposure at one of our four sponsorship levels: o Facebook: 4,191 o Instagram: 100+ followers 1. Platinum: 1848 Society ($30,000) Email Reach: ~25,000 students 2. Gold: Camp Randall Society ($20,000) Homecoming Web Traffic ~15-20k monthly visitors 3. Silver: Bucky’s Club ($10,000) Date: November 5-12, 2016 Wisconsin vs. Illinois 4. Bronze: Red & White Club ($3,000) UW Enrollment: ~42,818 Plus more add-ons! Alumni: ~399,862 Alumni in Wisconsin: ~146,810 (37%) International Alumni: ~14,467 (3%) Camp Randall Stadium: ~84,321 cap. (14,000 student section) 952.854.3100 [email protected] © Campus Media Group 2015 1 1848 Society – Platinum ($30,000) • Title sponsor of the UW-Homecoming Parade o Limited to -

Observatory Hill

Observatory Hill Cultural Landscape Inventory December 2005 (Revisions January 2010) Quinn Evans|Architects University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Landscape Architecture, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences Division of Facilities Planning and Management ©2010, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System University of Wisconsin-Madison Cultural Landscape Inventory Observatory Hill DEFINITIONS What is a “cultural landscape”? The following document is based on concepts and techniques developed by the National Park Service. The NPS has produced a series of manuals for identifying, describing, and maintaining culturally significant landscapes within the national park system.1 The National Park Service defines a cultural landscape as a geographic area, including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein[,] associated with a historic event, activity, or person, or [one] that exhibits other cultural or aesthetic values.2 In 1925, geographer Carl Sauer (1889-1975) summarized the process that creates cultural landscapes: “Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape the result.” 3 Similarly, the writer J. B. Jackson (1909-1996) looked upon the landscape as a composition of spaces made or modified by humans “to serve as infrastructure or background for our collective existence.”4 What is a “cultural landscape inventory”? 5 This cultural landscape inventory for Observatory Hill is one of eight such studies completed as part of the UW-Madison Cultural Landscape Resource Plan. Each inventory defines the boundaries of a distinct cultural landscape on campus, summarizes its history, describes its current condition, and makes recommendations about its treatment. In addition to these eight cultural landscape inventories, two companion documents address the archaeology and overall history of the campus. -

Download This

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Wisconsin COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Dane INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE ( lype an eniries — complete applicable sections) y/i (ftififi* oM3J fa/*//// lillliillillllilllll COMMON: Camp Randall AND/OR HISTORIC: - _\f>...A llii f|f::;;i;:;|:;;|;:;:::;;;;^ STREET AND NUMBER-. C (yrti/p K^'UXfl-*-* " Congressmen to be notified: Boundaries as shown on appended map Senator William Proxmire CITY OR TOWN: Senator Gaylord A. Nelson Madison Rep. Robert W. Kastenmeier STATE CQDE COL NTY: ' CODE Wisconsin 53706 55 Dane 025 |||il||l||ililtl:;:^ i/> CATEGORY OWNERSH.P STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC 2 Q District Q] Building S3 Public Public Acquisition: H Occupied Yes: O t, . , |X] Restricted 3 Site Q Structure D Privote Q In Process D Unoccupied "^ •.AptoA , —i „ " i ^DJJ-' nfes '''i ctod D Object D Both -Q Being Cons laerea Q p res ervotton v^rft ^"^^v. in progf^ssXjjyi'-i;^^ >\ u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) /\x >>,^. • XA :D 1 1 Agricultural 1 | Government (Xj Park r~l Commercial d Industrial Q Private Residence ?T) Other fSlfsiify) $$ ^ ^F> Ttd i- fXl Educational • CH Mi itary Q Religious \~\ Q'J£ ^ ^'^fzff to I | Entertainment 1 1 Museum | | Scientific -r V A -r*t? 1 A S? ' OWNER'S NAME: ^V/ ?S^->^^__-,-\"\'SX// STATE: University of Wisconsin , ' ' • \^^. __f/TT7\VW'^ Oj^-^t^' Wisconsin LLI STREET AND NUMBER: • UJ «/> i CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE Madison Wisconsin 55 COURTHOUSE, -

Onwisconsin Summer 2009

For University of Wisconsin-Madison Alumni and Friends The World At Their Feet Having global competence is a new expectation for students — but what does it mean? SUMMER 2009 Home. It’s where you feel connected. Revisiting the Boob Tube Children’s television is a potential teacher after all. As a member of the Wisconsin Alumni Association (WAA), you are an important part of the UW community. And you’ll continue to feel right at Origins of an American Author home as you connect with ideas, information and fellow Badgers. Relive the Madison days of Joyce Carol Oates MA’61. Membership is also a way to leave your mark on campus by supporting valuable scholarships, programs and services, and enjoying exclusive benefits Making a Splash like Badger Insider Magazine. So live your life as a Badger to the fullest. The “Miracle on the Hudson” copilot speaks out. Join today at uwalumni.com/membership, or call (888) 947-2586. Goatherd Guru Meet the big cheese of chèvre. ad_full pg_acquisition.indd 1 5/14/09 8:34:05 AM Third Wave s Mirus Bio s TomoTherapy s NimbleGen s SoftSwitching Technologies s ProCertus BioPharm s Stephen Babcock (center), with his butterfat tester, and colleagues W.A. Henry (left) and s s T.C. Chamberlin. GWC Technologies WICAB NeoClone Biotechnology In 1890, University of Wisconsin professor Stephen Babcock s Stratatech s ioGenetics s Deltanoid Pharmaceuticals s invented a device to test the amount of butterfat in milk. His discovery ended the practice of watering down milk and AlfaLight s GenTel Biosciences s Quintessence Biosciences created a cash cow for Wisconsin, putting the state on the map as a leader in dairy production and research. -

The Chair Called the Meeting to 8:30 Am

Minutes Campus Planning Committee Meeting February 23, 2017 Wisconsin Idea Room Education Building Committee Members FP&M Staff Mark Erickson Gary Brown Emmet Gaffney Stu LaRose Aris Georgiades Brent Lloyd Joel Gerrits Bo Muwahid Shawn Kaeppler Jim LaGro Visitors Sarah Mangelsdorf Chris Bruhn (L&S) Lesley Moyo Marcea Folk (DoIT) Mike Pflieger Allen Gierhart (L&S) Doug Reindl Jason King (Athletics) Doug Sabatke Alex Roe (UWSA) Jamie Schauer Kurt Stephenson (L&S) Karl Scholz Margaret Tennessen Kate VandenBosch The chair of the committee, Provost Sarah Mangelsdorf, called the meeting to order at 8:30 a.m. The committee approved the minutes of the November 17, 2016 meeting as distributed. Jason King, Senior Associate Athletic Director for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics presented the 2016 Athletics Master Plan Update. King told the committee that the previous plan was completed in 2007. After nearly ten years and a number of projects, the Division felt it was time to update and refresh the plan. They also felt it important to assess all their existing facilities so they could understand how best to allocate resources in the future. The previous plan had identified specific areas or “pods” across campus that served the Division’s student-athletes. Upgrades identified in that plan were made in each area: the LaBahn Arena was built on the east side of campus, the Goodman Softball facility on the west, and the Student-Athlete Performance Center near Camp Randall. A major feature of the Student-Athlete Performance Center was the consolidation of academic centers, strength and conditioning areas, and dining facilities in one area.