A Study of Gaelic Language and Culture in Cape Breton's Barra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Norse Element in the Orkney Dialect Donna Heddle

The Norse element in the Orkney dialect Donna Heddle 1. Introduction The Orkney and Shetland Islands, along with Caithness on the Scottish mainland, are identified primarily in terms of their Norse cultural heritage. Linguistically, in particular, such a focus is an imperative for maintaining cultural identity in the Northern Isles. This paper will focus on placing the rise and fall of Orkney Norn in its geographical, social, and historical context and will attempt to examine the remnants of the Norn substrate in the modern dialect. Cultural affiliation and conflict is what ultimately drives most issues of identity politics in the modern world. Nowhere are these issues more overtly stated than in language politics. We cannot study language in isolation; we must look at context and acculturation. An interdisciplinary study of language in context is fundamental to the understanding of cultural identity. This politicising of language involves issues of cultural inheritance: acculturation is therefore central to our understanding of identity, its internal diversity, and the porousness or otherwise of a language or language variant‘s cultural borders with its linguistic neighbours. Although elements within Lowland Scotland postulated a Germanic origin myth for itself in the nineteenth century, Highlands and Islands Scottish cultural identity has traditionally allied itself to the Celtic origin myth. This is diametrically opposed to the cultural heritage of Scotland‘s most northerly island communities. 2. History For almost a thousand years the language of the Orkney Islands was a variant of Norse known as Norroena or Norn. The distinctive and culturally unique qualities of the Orkney dialect spoken in the islands today derive from this West Norse based sister language of Faroese, which Hansen, Jacobsen and Weyhe note also developed from Norse brought in by settlers in the ninth century and from early Icelandic (2003: 157). -

Dialectal Diversity in Contemporary Gaelic: Perceptions, Discourses and Responses Wilson Mcleod

Dialectal diversity in contemporary Gaelic: perceptions, discourses and responses Wilson McLeod 1 Introduction This essay will address some aspects of language change in contemporary Gaelic and their relationship to the simultaneous workings of language shift and language revitalisation. I focus in particular on the issue of how dialects and dialectal diversity in Gaelic are perceived, depicted and discussed in contemporary discourse. Compared to many minoritised languages, notably Irish, dialectal diversity has generally not been a matter of significant controversy in relation to Gaelic in Scotland. In part this is because Gaelic has, or at least is depicted as having, relatively little dialectal variation, in part because the language did undergo a degree of grammatical and orthographic standardisation in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with the Gaelic of the Bible serving to provide a supra-dialectal high register (e.g. Meek 1990). In recent decades, as Gaelic has achieved greater institutionalisation in Scotland, notably in the education system, issues of dialectal diversity have not been prioritised or problematised to any significant extent by policy-makers. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been some evidence of increasing concern about the issue of diversity within Gaelic, particularly as language shift has diminished the range of spoken dialects and institutionalisation in broadcasting and education has brought about a degree of levelling and convergence in the language. In this process, some commentators perceive Gaelic as losing its distinctiveness, its richness and especially its flavour or blas. These responses reflect varying ideological perspectives, sometimes implicating issues of perceived authenticity and ownership, issues which become heightened as Gaelic is acquired by increasing numbers of non-traditional speakers with no real link to any dialect area. -

Sport & Activity Directory Uist 2019

Uist’s Sport & Activity Directory *DRAFT COPY* 2 Foreword 2 Welcome to the Sport & Activity Directory for Uist! This booklet was produced by NHS Western Isles and supported by the sports division of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and wider organisations. The purpose of creating this directory is to enable you to find sports and activities and other useful organisations in Uist which promote sport and leisure. We intend to continue to update the directory, so please let us know of any additions, mistakes or changes. To our knowledge the details listed are correct at the time of printing. The most up to date version will be found online at: www.promotionswi.scot.nhs.uk To be added to the directory or to update any details contact: : Alison MacDonald Senior Health Promotion Officer NHS Western Isles 42 Winfield Way, Balivanich Isle of Benbecula HS7 5LH Tel No: 01870 602588 Email: [email protected] . 2 2 CONTENTS 3 Tai Chi 7 Page Uist Riding Club 7 Foreword 2 Uist Volleyball Club 8 Western Isles Sports Organisations Walk Football (40+) 8 Uist & Barra Sports Council 4 W.I. Company 1 Highland Cadets 8 Uist & Barra Sports Hub 4 Yoga for Life 8 Zumba Uibhist 8 Western Isles Island Games Association 4 Other Contacts Uist & Barra Sports Council Members Ceolas Button and Bow Club 8 Askernish Golf Course 5 Cluich @ CKC 8 Benbecula Clay Pigeon Club 5 Coisir Ghaidhlig Uibhist 8 Benbecula Golf Club 5 Sgioba Drama Uibhist 8 Benbecula Runs 5 Traditional Spinning 8 Berneray Coastal Rowing 5 Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Classes 8 Berneray Community Association -

Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report for the Bras D'or Lakes

Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report for the Bras d’Or Lakes, Nova Scotia M. Parker, M. Westhead, P. Doherty and J. Naug Oceans and Habitat Branch Maritimes Region Fisheries and Oceans Canada Bedford Institute of Oceanography PO Box 1006 Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2 2007 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2789 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribution is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department’s annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1–900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 901–1425 were issued as Manuscript Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 1426–1550 were issued as Department of Fisheries and the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Manuscript Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 1551. Manuscript reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

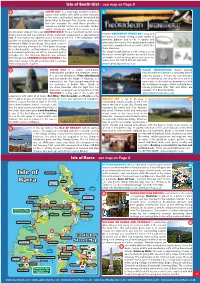

Isle of Barra - See Map on Page 8

Isle of South Uist - see map on Page 8 65 SOUTH UIST is a stunningly beautiful island of 68 crystal clear waters with white powder beaches to the west, and heather uplands dominated by Beinn Mhor to the east. The 20 miles of machair that runs alongside the sand dunes provides a marvellous habitat for the rare corncrake. Golden eagles, red grouse and red deer can be seen on the mountain slopes to the east. LOCHBOISDALE, once a major herring port, is the main settlement and ferry terminal on the island with a population of approximately Visit the HEBRIDEAN JEWELLERY shop and 300. A new marina has opened, and is located at the end of the breakwater with workshop at Iochdar, selling a wide variety of facilities for visiting yachts. Also newly opened Visitor jewellery, giftware and books of quality and Information Offi ce in the village. The island is one of good value for money. This quality hand crafted the last surviving strongholds of the Gaelic language jewellery is manufactured on South Uist in the in Scotland and the crofting industries of peat cutting Outer Hebrides. and seaweed gathering are still an important part of The shop in South Uist has a coffee shop close by everyday life. The Kildonan Museum has artefacts the beach, where light snacks are served. If you from this period. ASKERNISH GOLF COURSE is the are unable to visit our shop, please visit us on our oldest golf course in the Western Isles and is a unique online store. Tel: 01870 610288. HS8 5QX. -

Bras D'or Lakes Scenic Drive Bras D'or Lakes Scenic Drive

BrasBras d’Ord’Or LakesLakes ScenicScenic DriveDrive Reflections on the beautiful Bras d’Or Visitor Information Finest Sailing in the World Centres WELCOME TO CAPE BRETON’S rolling heartland, where the highlands meet Baddeck E15, 295-1911 the lowlands along the shores of the island’s beautiful inland sea— Little Narrows, 756-2413 the Bras d’Or Lakes. The Bras d’Or Lakes Scenic Drive circles the lake Louisbourg E17, 733-2720 along shoreline roads that offer an ever-changing panorama Margaree Forks D14, 248-2803 North Sydney D16, 794-7719 of woodlands, farms and villages, and are ideal for walking, biking and bird- ≈ Port Hastings F13, 625-4201 watching. The region is a major nesting area for bald eagles, and these impressive Port Hood E13, 787-2521 birds can often be seen soaring aloft or perched on shoreline trees. St. Peter’s F14, 535-2185 There’s something new around every corner along this route. Experience the daily Sydney River E16, 539-9876 life of the early Scottish settlers at the Nova Scotia Highland Village Museum. Most Visitor Information Centres At Marble Mountain Museum you can learn about marble quarrying in the late are open mid-May to mid-October. Call the above numbers or 1800s, and the Orangedale Railway Station Museum offers a special look at late 1-800-565-0000. th 19 -century trains and train travel. ≈ Provides information for Known for its gentle, fog-free waters, beautiful anchorages, and hundreds of all of Nova Scotia coves and islands, the lakes are an international cruising destination, attracting cbisland.com hundreds of boating enthusiasts every year. -

C S a S S C C S

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Proceedings Series 2006/007 Série des comptes rendus 2006/007 Proceedings of the Maritimes Compte rendu du Processus Regional Advisory Process consultatif régional des Maritimes Evaluation of the Ecosystem Rapport d’aperçu et d’évaluation de Overview and Assessment Report l’écosystème du lac Bras d’Or, for the Bras d’Or Lakes, Nova Scotia Nouvelle-Écosse 2 – 3 November 2005 Les 2 et 3 novembre 2005 Wagmatcook Cultural Centre Wagmatcook Cultural Centre Wagmatcook, Cape Breton, Wagmatcook, Cap-Breton Nova Scotia Nouvelle-Écosse T. Worcester (Chair) T. Worcester (président) Fisheries and Oceans Canada / Pêches et Océans Canada Bedford Institute of Oceanography / Institute océanographique de Bedford Dartmouth, Nova Scotia / Dartmouth, N.-É. B2Y 4A2 Canada June 2006 juin 2006 Foreword The purpose of these proceedings is to archive the activities and discussions of the meeting, including research recommendations, uncertainties, and to provide a place to formally archive official minority opinions. As such, interpretations and opinions presented in this report may be factually incorrect or mis-leading, but are included to record as faithfully as possible what transpired at the meeting. No statements are to be taken as reflecting the consensus of the meeting unless they are clearly identified as such. Moreover, additional information and further review may result in a change of decision where tentative agreement had been reached. Avant-propos Le présent compte rendu fait état des activités et des discussions qui ont eu lieu à la réunion, notamment en ce qui concerne les recommandations de recherche et les incertitudes; il sert aussi à consigner en bonne et due forme les opinions minoritaires officielles. -

ON ISLAY PLACE-NAMES. by CAPT. F. W. L. THOMAS, R.N., F.S.A. Soot

I. ON ISLAY PLACE-NAMES CAPTy B . W.F . L. THOMAS, R.N., F.S.A. Soot. Whe examinatioe nth e Lewith f no s Place-Names—wit e vieth hf wo ascertaining to what extent the Scandinavian influence had been im- pressed there—was finished, it seemed very desirable that the name- system of the Southern Hebrides, particularly Tslay, should be inquired intoj for comparison with that of Lewis; but having no local acquaint- ance with the island d onlan ,y ver e d mapsb y ba e attemp o t th , d ha t postponed. But having lately the offer of assistance from Mr. Hector Maclean of Ballygrant, Islay, who, besides having a critical knowledge of Gaelic, is thoroughly acquainted with the topography of Islay, it was considered safe to proceed, but without his co-operation this account of Islay Place-Names coul t havdno e been written. This paper must be considered complementary to that on Lewis Place- Names, to which the reader is referred for many remarks bearing on the present subject t whichbu , avoio t , d repetition omittee ar , d here,. formee th n I r pape methoe th r s detailedi whicy db namee hth s them- selves were determined and their analysis performed,—and the same system has been followed in this. To prevent any unconscious selection, and as affordin faia g r exampl e name-systeth f eo mIslayn i lise farmf o th ,t n i s the Valuation Rol f Argyllshiro l s takea basis wa es a n . These names VOL. -

Cape Breton. the Unspoiled Summerland of America

CapeBieton CapeBifetoiv' 3feUnfpoilecT 3fellnjpoilecT SUMMERIAND SUMMERLAND i iii.i i -.... £«*- CAPE BRETON •o^ .- ::~ ' • ' : m Maclcod's Photo Studio, Sydney, N. Surf Scene near Louisbourg Waves topped with fluffy white caps of spray, getting higher and gaining speed as they near the shore, then booming and crashing, with spume flying, the monsters are laid low with only little ripples left to dance awhile on the shore before the run out for another fling [2] FOREWORD f J ^IVE YOUNG MEN were seated in the renders instructive the story of America. It's a land I I —, smoking room of a well-known New fairly breathing tradition and romance. Old World ^^ | England Club one evening late last May. association—New World achievement-—these are all / I "You chaps have been all over the world," connected up in Cape Breton!" ^^ said one of them. "Now, I have a vaca- "By all means go to Cape Breton," said the ETH- tion of some weeks due me. Where shall I spend it, NOLOGIST. "There in the radius of less than a together with my family, to the best advantage and half day's journey, are four races, speaking four dif- at reasonable cost?" ferent languages (though all speak English). There "In Cape Breton," said the SPORTSMAN. "There you will find quaint villages whose inhabitants speak you will find the best salmon fly-fishing in the world. the language of Old France and live after the manner Salmon up to and over fifty pounds are landed from of their old world forefathers of the 17th century; those pools and streams. -

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: an Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions by Anna Wright BMus, Edinburgh Napier University, 2015 MMus, University of British Columbia, 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ethnomusicology) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) April 2020 © Anna Wright, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions submitted by Anna Wright in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Ethnomusicology Examining Committee: Nathan Hesselink Supervisor, Chair, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC Michael Tenzer Supervisory Committee Member, Professor, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC ii Abstract This thesis examines the use of seist chorus sections in the Scottish Gaelic song tradition. These sections consist of nonsense syllables, or vocables. Although lacking semantic meaning, such vocables often provoke the joining in of the audience or listening group. The use of these vocable sections can be seen to have evolved in both their physical (sonic) characteristics and their social use and function over time while still maintaining a marked presence in Scottish Gaelic music across many genres and generations. I briefly examine theories surrounding seist vocables’ inception, interview three practitioners of Gaelic song about seist choruses’ inception and evolving function, examine four songs dating from a period spanning 1601-2016, and relate my findings to Scotland’s constantly evolving social and political climate. -

Land and Belonging in Gaelic Nova Scotia

“Dh’fheumadh iad àit’ a dheanamh” (They would have to make a Place): LAND AND BELONGING IN GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA © Shamus Y. MacDonald A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland December 2017 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract: This thesis explores the way land has been perceived, described and experienced by Scottish Gaels in Nova Scotia. It examines how attitudes towards land are maintained and perpetuated through oral traditions and how oral history, legends and place names have fostered a sense of belonging in an adopted environment. Drawing on archival research and contemporary ethnographic fieldwork in Gaelic and English, it explores how people give anonymous aspects of the natural and built environment meaning, how personal and cultural significance is attached to landscapes, and how oral traditions contribute to a sense of place. Exploring a largely unofficial tradition, my thesis includes a survey of Gaelic place names in Nova Scotia that shows how settlers and their descendants have interpreted their surroundings and instilled them with a sense of Gaelic identity. It also considers local traditions about emigration and settlement, reflecting on the messages these stories convey to modern residents and how they are used to construct an image of the past that is acceptable to the present. Given its focus on land, this work investigates the protective attitude towards property long ascribed to Highland Gaels in the province, considering local perspectives of this claim and evaluating its origins.