Chapter 20 – the Last Great Islamic Empires, 1500-1800

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

NIOS 12Th History Syllabus

SYLLABUS Total Reading Time : 240 Hours Max. Marks 100 Number of Papers One RATIONALE History is the scientific study of human beings and the evolution of human society in point of time and in different ages. As such it occupies all important place in the school curricu- lum. It is, therefore, taught as a general subject forming a part of Social Science both at the Middle and the Secondary Stages. At the Middle Stage, entire Indian History is covered, while at the Secondary Stage, the land marks in the development of human society are taught. At the Senior Secondary Stage, History becomes an elective subject. Its main thrust is to bridge the gap between the presence of change-oriented technologies of today and the con- tinuity of our cultural tradition so as to ensure that the coming generation will represent the fine synthesis between change and continuity. It is, therefore, deemed essential to take up the entire Indian History from the Ancient to the Modem period for Senior Secondary Stage. The rationale for taking up the teaching of History at this stage is : 1. to promote an understanding of the major stages in the evolution of Indian society through the ages. 2. to develop an understanding of the historical forces responsible for the evolution of Indian society in the Ancient, Medieval and Modem times. 3. to develop an appreciation of (i) the diverse cultural and social systems of the people living indifferent parts of the country. (ii) the richness, variety and composite nature of Indian culture. (iii) the growth of various components of Indian culture, legitimate pride in the achieve- ment of Indian people in. -

Indian History - Dynasties #4

TISS GK Preparation | Indian History - Dynasties #4 TISS GK Preparation Series: GK is a very important section for TISS especially since the verbal and the quant sections are relatively easy. Hence, getting a good score in GK can easily be the difference between getting a TISS call and not getting one. To help you ace this section, we are starting a series of articles devoted to topics commonly asked in the TISS GK section. We hope that this will help you in your preparation. Every article will also be available in PDF format. Here is our #4 article in this series: Indian History – Dynasties. Indian History is a very important topic for TISS with a lot of questions asked on dynasties, ancient India, etc. To help you, we have compiled a list of the important dynasties of India with a little detail on each. Also, this has been presented in a chronological order. Sr. Dynasty/Empire Detail No. 1 Magadha The core of this kingdom was the area of Bihar south of the Ganges; its first capital was Rajagriha (modern Rajgir) then Pataliputra (modern Patna). Magadha played an important role in the development of Jainism and Buddhism, and two of India's greatest empires, the Maurya Empire and Gupta Empire, originated from Magadha. 2 Maurya The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) was the first empire to unify India into one state, and was the largest on the Indian subcontinent. The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya in Magadha (in modern Bihar) when he overthrew the Nanda Dynasty. Chandragupta's son Bindusara succeeded to the throne around 297 BC. -

Medieval India TNPSC GROUP – I & II

VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE Medieval India TNPSC GROUP – I & II An ISO 9001 : 2015 Institution | Providing Excellence Since 2011 Head Office Old No.52, New No.1, 9th Street, F Block, 1st Avenue Main Road, (Near Istha siddhi Vinayakar Temple), Anna Nagar East – 600102. Phone: 044-2626 5326 | 98844 72636 | 98844 21666 | 98844 32666 Branches SALEM KOVAI No.189/1, Meyanoor Road, Near ARRS Multiplex, No.347, D.S.Complex (3rd floor), (Near Salem New bus Stand), Nehru Street,Near Gandhipuram Opp. Venkateshwara Complex, Salem - 636004. Central Bus Stand, Ramnagar, Kovai - 9 Ph: 0427-2330307 | 95001 22022 Ph: 75021 65390 Educarreerr Location VIVEKANANDHA EDUCATIONA PATRICIAN COLLEGE OF ARTS SREE SARASWATHI INSTITUTIONS FOR WOMEN AND SCIENCE THYAGARAJA COLLEGE Elayampalayam, Tiruchengode - TK 3, Canal Bank Rd, Gandhi Nagar, Palani Road, Thippampatti, Namakkal District - 637 205. Opp. to Kotturpuram Railway Station, Pollachi - 642 107 Ph: 04288 - 234670 Adyar, Chennai - 600020. Ph: 73737 66550 | 94432 66008 91 94437 34670 Ph: 044 - 24401362 | 044 - 24426913 90951 66009 www.vetriias.com © VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE First Edition – 2015 Second Edition – 2019 Pages : 114 Size : (240 × 180) cm Price : 220/- Published by: VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE F Block New No. 1, 9th Street, 1st Avenue main Road, Chinthamani, Anna Nagar (E), Chennai – 102. Phone: 044-2626 5326 | 98844 72636 | 98844 21666 | 98844 32666 www.vetriias.com E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] Feedback: [email protected] © All rights reserved with the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher, will be responsible for the loss and may be punished for compensation under copyright act. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

History of Modern India (1857-1947) Semester

F.Y.B.A. (History) History of Modern India (1857-1947) Semester - I Syllabus objectives outcome Module I: Growth of Political Awakening The course is The students will (a) Revolt of 1857 – Causes and designed to make understand Growth of Consequences the student aware Political Awakening (b) Contribution of the Provincial about the making of including Revolt of Associations modern India and 1857 and Foundation (c) Foundation of Indian National the struggle for of Indian National Congress. independence. Congress. Module II: Trends in Indian Nationalism To impart (a) Moderates information about They will know (b) Extremists Trends in Indian Trends in Indian (c) Revolutionary Nationalists Nationalism and Nationalism. Module III: Gandhian Movements Gandhian (a) Non Co-operation Movement Movements The students will (b) Civil Disobedience Movement To inform students know the Non Co- (c) Quit India Movement abou constitutional operation Movement Module IV: Towards Independence and developments and and Civil Partition Independence Disobedience (a) The Indian Act of 1935 Movement (b) Attempts to Resolve the Constitutional Deadlock -The Cripps Mission, The Cabinet Mission and the Mountbatten Plan F.Y.B.A. (History) History of Modern India: Society and Economy Semester – II Syllabus objectives outcome Module I: Socio Religious Reform The course is The students will Movements: Reforms and Revival designed to make understand Socio (a) Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj and the student aware Religious Reform Ramakrishna Mission about Socio Movements: Reforms -

Iasbaba.Com History Compilation-Prelims

IASbaba.com History Compilation-Prelims 1. In British India, what is ‘Dastak’ known for? 1. A permit exempting European traders, mostly of the British East India Company, from paying customs or transit duties on their private trade. 2. A permit regulating internal trade, mostly for Indian traders. 3. Fee charged by Indian rulers from European Traders when they trade into their territory 4. Fee charged by British government for the regulation of domestic trade. Solution: 1 Explanation: Dastak, in 18th-century Bengal, a permit exempting European traders, mostly of the British East India Company, from paying customs or transit duties on their private trade. The name came from the Persian word for “pass.” The practice was introduced by Robert Clive, one of the creators of British power in India, when he had Mir Jaʿfar installed as nawab of Bengal in 1757. The attempt of Mir Jaʿfar’s successor, Mir Qāsim, to annul the use of dastaks led to his overthrow in 1763–64 and the exercise of overt control of Bengal by the British. Free dastaks for private trade were finally abolished by Warren Hastings, governor of Bengal (1775). The system put the Indian trader at a grave disadvantage in competing with the European and was an important factor in the impoverishment of Bengal under early British rule. Iasbaba.com Page 1 IASbaba.com 2. Consider the following statements with respect to administration of Maratha and Mughal Empires 1. The revenue system of Marathas was progressive unlike Mughals who were mainly interested in raising revenues from the helpless peasantry. 2. -

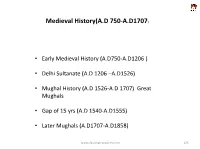

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707)

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707) • Early Medieval History (A.D750-A.D1206 ) • Delhi Sultanate (A.D 1206 –A.D1526) • Mughal History (A.D 1526-A.D 1707) Great Mughals • Gap of 15 yrs (A.D 1540-A.D1555) • Later Mughals (A.D1707-A.D1858) www.classmateacademy.com 125 The years AD 750-AD 1206 • Origin if Indian feudalism • Economic origin beginning with land grants first by satavahana • Political origin it begins in Gupta period ,Samudragupta started it (samantha system) • AD750-AD950 peak of feudalism ,it continues under sultanate but its nature changes they allowed fuedalism to coexist. www.classmateacademy.com 126 North India (A.D750 –A.D950) Period of Triangular Conflict –Pala,Prathihara,Rashtrakutas Gurjara Prathiharas-West Pala –Pataliputra • Naga Bhatta -1 ,defends wetern border • Started by Gopala • Mihira bhoja (Most powerful) • Dharmapala –most powerful,Patron of Buddhism • Capital -Kannauj Est.Vikramshila university Senas • Vijayasena founder • • Last ruler –Laxmana sena Rashtrakutas defeated by • Dantidurga-founder, • Bhakthiyar Khalji(A.D1206) defeated Badami Chalukyas (Dasavatara Cave) • Krishna-1 Vesara School of architecture • Amoghvarsha Rajputs and Kayasthas the new castes of Medival India New capital-Manyaketa Patron-Jainism &Kannada Famous works-Kavirajamarga,Ratnamalika • Krishna-3 last powerful ruler www.classmateacademy.com 127 www.classmateacademy.com 128 www.classmateacademy.com 129 www.classmateacademy.com 130 www.classmateacademy.com 131 Period of mutlicornered conflict-the 4 Agni Kulas(AD950-AD1206) Chauhans-Ajayameru(Ajmer) Solankis Pawars Ghadwala of Kannauj • Prithviraj chauhan-3 Patronn of Jainsim Bhoja Deva -23 classical Jayachandra (last) • PrthvirajRasok-ChandBardai Dilwara temples of Mt.Abu works in sanskrit • Battle of Tarain-1 Nagara school • Battle of tarain-2(1192) Chandellas of bundelKhand Tomars of Delhi Kajuraho AnangaPal _Dillika www.classmateacademy.com 132 Meanwhile in South India.. -

George Thomas and the Frontier of the British Empire 1781-1802

“If It Were My Way, All This Ought to Be Red”: George Thomas and the Frontier of the British Empire 1781-1802 A Senior Honors Project Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For Bachelor of History with Honors By Devon Hideo Miller 12/02/2017 Committee: Dr. Marcus Daniel, Mentor Dr. Peter H. Hoffenberg Acknowledgements To the teachers, coaches, and professors who have supported me over the course of my education. Everything I have learned in academe is the result of your endeavors and this is a debt I will never be able to repay. To my friends and family who tolerated the library hermit I became over the course of this paper. I do not know where I would be without your support. You were the spark that lit my ambition which led me down this path, and the fuel which carried me through. To my thesis committee members: Dr. Marcus Daniel and Dr. Peter H. Hoffenberg, thank you for your time, effort, patience, and expert advice, especially given the rather unconventional time-schedule of this project. Additionally, I would like to thank you for slogging through the veritable garbled tome that constituted the first draft. This is the result of your generous investment of time and effort. I would especially like to thank my Mentor Dr. Marcus Daniel. Your support has been essential, and I cannot express how grateful I am for your suggestions. i Abstract In 1805, a printer in England published a tale of imperialism, conquest and tragic loss from a memoir from Calcutta, India. -

Rise of the Marathas1/ Rakesh Kumar

E- Content/ Medieval India/ B.A.II(H) Rise of the Marathas1/ Rakesh kumar/ SMD College, Punpun. RISE OF THE MARATHAS The rise of the Marathas in India is an important chapter of Medieval Indian history. The emergence of Marathas as a political power had a number of consequences. It shows us the possibilities of the rise of a Hindu power in Modern India as enumerated in the HINDU PAD PADSHAHI of Baji Rao I. a possibility that was cut short by the English during Anglo- Maratha wars. As the chapter on the Marathas unfold, we discuss here, in this e – content, some of the underlying causes which led to the rise of the Maratha power in India. This is first of the series of lectures on the topic – Rise of the Marathas. GEOGRAPHICAL REGION: The early rise of the Marathas mostly comprised of the regions specified below. The region specified in this unfolding of events are western coastal areas of Konkan, Khandesh, Berar, Nagpur, areas of the south and some areas of the Nizam. This whole area was known as Marathwada in medieval times, according to historian Bhandarkar, an expert in the history of the Marathas. The people collectively known as the Marathas comprised of the Rathis, Rashtriks and Rathiks, who occupied these areas. In due course of time especially 17th century, they were able to organize themselves into a cohesive force whose 1 sword and diplomacy conquered and held sway over major parts of India in the Deccan and north as well. CAUSES OF THE RISE OF THE MARATHAS: Historian Grant Duff opines that the Marathas came out of the Sahayadri mountains like wild fire. -

Department of History

H.H. THE RAJAHA’S COLLEGE (AUTO), PUDUKKOTTAI - 622001 Department of History II MA HISTORY HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E THIRD SEMESTER 18PHS7 MA HISTORY SEMESTER : III SUB CODE : 18PHS7 CORE COURSE : CCVIII CREDIT : 5 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E Objectives ● To understand the colonial hegemony in India ● To Inculcate the knowledge of solidarity shown by Indians against British government ● To know about the social reform sense through the historical process. ● To know the effect of the British rule in India. ● To know the educational developments and introduction of Press in India. ● To understand the industrial and agricultural bases set by the British for further developments UNIT – I Decline of Mughals and Establishment of British Rule in India Sources – Decline of Mughal Empire – Later Mughals – Rise of Marathas – Ascendancy under the Peshwas – Establishment of British Rule – the French and the British rivalry – Mysore – Marathas Confederacy – Punjab Sikhs – Afghans. UNIT – II Structure of British Raj upto 1857 Colonial Economy – Rein of Rural Economy – Industrial Development – Zamindari system – Ryotwari – Mahalwari system – Subsidiary Alliances – Policy on Non intervention – Doctrine of Lapse – 1857 Revolt – Re-organization in 1858. UNIT – III Social and cultural impact of colonial rule Social reforms – English Education – Press – Christian Missionaries – Communication – Public services – Viceroyalty – Canning to Curzon. ii UNIT – IV India towards Freedom Phase I 1885-1905 – Policy of mendicancy – Phase II 1905-1919 – Moderates – Extremists – terrorists – Home Rule Movement – Jallianwala Bagh – Phase III 1920- 1947 – Gandhian Era – Swaraj party – simon commission – Jinnah‘s 14 points – Partition – Independence. UNIT – V Constitutional Development from 1773 to 1947 Regulating Act of 1773 – Charter Acts – Queen Proclamation – Minto-Morley reforms – Montague Chelmsford reforms – govt. -

4. Maharashtra Before the Times of Shivaji Maharaj

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 3.3.2017 HISTORY AND CIVICS STANDARD SEVEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune - 411 004. First Edition : 2017 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Reprint : September 2020 Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee : Cartographer : Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Shri. Ravikiran Jadhav Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Coordination : Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Mogal Jadhav Dr Abhiram Dixit, Member Special Officer, History and Civics Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Varsha Sarode Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Subject Assistant, History and Civics Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Translation : Shri. Aniruddha Chitnis Civics Subject Committee : Shri. Sushrut Kulkarni Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Smt. Aarti Khatu Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni, Member Scrutiny : Dr Mohan Kashikar, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Vaijnath Kale, Member Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Coordination : Dhanavanti Hardikar History and Civics Study Group : Academic Secretary for Languages Shri. Rahul Prabhu Dr Raosaheb Shelke Shri. Sanjay Vazarekar Shri. Mariba Chandanshive Santosh J. Pawar Assistant Special Officer, English Shri. Subhash Rathod Shri. Santosh Shinde Smt Sunita Dalvi Dr Satish Chaple Typesetting : Dr Shivani Limaye Shri.