Leonardo Tondo's Interview of Roland Kuhn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WO 2015/072852 Al 21 May 2015 (21.05.2015) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/072852 Al 21 May 2015 (21.05.2015) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 36/84 (2006.01) A61K 31/5513 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 31/045 (2006.01) A61P 31/22 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, A61K 31/522 (2006.01) A61K 45/06 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, PCT/NL20 14/050780 KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, (22) International Filing Date: MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, 13 November 2014 (13.1 1.2014) PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, (25) Filing Language: English TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 61/903,430 13 November 2013 (13. 11.2013) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, (71) Applicant: RJG DEVELOPMENTS B.V. -

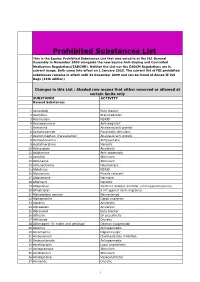

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

WO 2015/072853 Al 21 May 2015 (21.05.2015) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/072853 Al 21 May 2015 (21.05.2015) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 45/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/5513 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 31/045 (2006.01) A61K 31/5517 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, A61K 31/522 (2006.01) A61P 31/22 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, A61K 31/551 (2006.01) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (21) International Application Number: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, PCT/NL20 14/050781 MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (22) International Filing Date: PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 13 November 2014 (13.1 1.2014) SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, 61/903,433 13 November 2013 (13. -

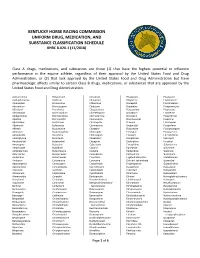

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Synthesis of Chlorinated Tetracyclic Compounds and Testing for Their Potential Antidepressant Effect in Mice

molecules Communication Synthesis of Chlorinated Tetracyclic Compounds and Testing for Their Potential Antidepressant Effect in Mice Usama Karama 1,*, Mujeeb A. Sultan 1, Abdulrahman I. Almansour 1 and Kamal Eldin El-Taher 2 Received: 20 November 2015 ; Accepted: 31 December 2015 ; Published: 5 January 2016 Academic Editor: Maria Emília de Sousa 1 Chemistry Department, College of Science, King Saud University, P. O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (M.A.S.); [email protected] (A.I.A.) 2 Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, P. O. Box 2457, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +966-114-675-894 Abstract: The synthesis of the tetracyclic compounds 1-(4,5-dichloro-9,10-dihydro-9,10-ethanoanthracen- 11-yl)-N-methylmethanamine (5) and 1-(1,8-dichloro-9,10-dihydro-9,10-ethanoanthracen-11-yl)- N-methylmethanamine (6) as a homologue of the anxiolytic and antidepressant drugs benzoctamine and maprotiline were described. The key intermediate aldehydes (3) and (4) were successfully synthesized via a [4 + 2] cycloaddition between acrolein and 1,8-dichloroanthracene. The synthesized compounds were investigated for antidepressant activity using the forced swimming test. Compounds (5), (6) and (3) showed significant reduction in the mice immobility indicating significant antidepressant effects. These compounds significantly reduced the immobility times at a dose 80 mg/kg by 84.0%, 86.7% and 71.1% respectively. Keywords: chlorinated tetracyclic; antidepressants; synthesis; forced swimming test 1. Introduction Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder and is among the 10 leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1,2]. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

ROSITA Project

Index I N D E X Page Introduction 3 Deliverable D1 “Drugs and medicines that are suspected to have a detrimental impact on road user performance” 5 - Executive summary 7 - Introduction 9 - Epidemiological data 12 - Pharmaco-Epidemiological data: overview table 17 - Illicit Drugs with an Influence on Driving Performance 19 - Medicinal Drugs with an Influence on Driving Performance 26 - Classification of Medicinal Drugs According to their Influence on Driving Performance and Warning Systems in European Countries 32 - Glossary 41 - Acknowledgements 41 - References 42 Deliverable D2 “Inventory of State-of-the-Art road side drug testing equipment” 45 - Executive summary 47 - Introduction 49 - List of Devices 51 - Cross-reactivities of the “AMPHETAMINE” type devices 75 - Cross-reactivities of the “METHAMPHETAMINE” type devices 77 - Cross-reactivities of the “CANNABIS” type devices 79 - Cross-reactivities of the “COCAINE” type devices 80 - Cross-reactivities of the “OPIATES” type devices 82 - Cross-reactivities of the “BENZODIAZEPINES” type devices 86 - List of Manufacturers and Distributors 88 i ROSITA project - Conclusions 93 - References 102 Deliverable D3 “Operational, user and legal requirements across EU member states for roadside drug testing equipment” 103 - Executive summary 105 - Introduction 108 - Legal Requirements 109 · Austria 109 · Belgium 110 · Czech Republic 112 · Denmark 113 · Finland 114 · France 115 · Germany 117 · Greece 118 · Iceland 119 · Ireland 120 · Italy 121 · Luxembourg 123 · The Netherlands 124 · Norway 125 · Poland -

2021 Equine Prohibited Substances List

2021 Equine Prohibited Substances List . Prohibited Substances include any other substance with a similar chemical structure or similar biological effect(s). Prohibited Substances that are identified as Specified Substances in the List below should not in any way be considered less important or less dangerous than other Prohibited Substances. Rather, they are simply substances which are more likely to have been ingested by Horses for a purpose other than the enhancement of sport performance, for example, through a contaminated food substance. LISTED AS SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY BANNED 1-androsterone Anabolic BANNED 3β-Hydroxy-5α-androstan-17-one Anabolic BANNED 4-chlorometatandienone Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androst-2-ene-17one Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3α, 17α-diol Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3α, 17β-diol Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3β, 17α-diol Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3β, 17β-diol Anabolic BANNED 5β-Androstane-3α, 17β-diol Anabolic BANNED 7α-Hydroxy-DHEA Anabolic BANNED 7β-Hydroxy-DHEA Anabolic BANNED 7-Keto-DHEA Anabolic CONTROLLED 17-Alpha-Hydroxy Progesterone Hormone FEMALES BANNED 17-Alpha-Hydroxy Progesterone Anabolic MALES BANNED 19-Norandrosterone Anabolic BANNED 19-Noretiocholanolone Anabolic BANNED 20-Hydroxyecdysone Anabolic BANNED Δ1-Testosterone Anabolic BANNED Acebutolol Beta blocker BANNED Acefylline Bronchodilator BANNED Acemetacin Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug BANNED Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant CONTROLLED Acepromazine Sedative BANNED Acetanilid Analgesic/antipyretic CONTROLLED Acetazolamide Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor BANNED Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant CONTROLLED Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic BANNED Acetophenazine Antipsychotic BANNED Acetophenetidin (Phenacetin) Analgesic BANNED Acetylmorphine Narcotic BANNED Adinazolam Anxiolytic BANNED Adiphenine Antispasmodic BANNED Adrafinil Stimulant 1 December 2020, Lausanne, Switzerland 2021 Equine Prohibited Substances List . Prohibited Substances include any other substance with a similar chemical structure or similar biological effect(s). -

Drug/Substance Trade Name(S)

A B C D E F G H I J K 1 Drug/Substance Trade Name(s) Drug Class Existing Penalty Class Special Notation T1:Doping/Endangerment Level T2: Mismanagement Level Comments Methylenedioxypyrovalerone is a stimulant of the cathinone class which acts as a 3,4-methylenedioxypyprovaleroneMDPV, “bath salts” norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It was first developed in the 1960s by a team at 1 A Yes A A 2 Boehringer Ingelheim. No 3 Alfentanil Alfenta Narcotic used to control pain and keep patients asleep during surgery. 1 A Yes A No A Aminoxafen, Aminorex is a weight loss stimulant drug. It was withdrawn from the market after it was found Aminorex Aminoxaphen, Apiquel, to cause pulmonary hypertension. 1 A Yes A A 4 McN-742, Menocil No Amphetamine is a potent central nervous system stimulant that is used in the treatment of Amphetamine Speed, Upper 1 A Yes A A 5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, and obesity. No Anileridine is a synthetic analgesic drug and is a member of the piperidine class of analgesic Anileridine Leritine 1 A Yes A A 6 agents developed by Merck & Co. in the 1950s. No Dopamine promoter used to treat loss of muscle movement control caused by Parkinson's Apomorphine Apokyn, Ixense 1 A Yes A A 7 disease. No Recreational drug with euphoriant and stimulant properties. The effects produced by BZP are comparable to those produced by amphetamine. It is often claimed that BZP was originally Benzylpiperazine BZP 1 A Yes A A synthesized as a potential antihelminthic (anti-parasitic) agent for use in farm animals. -

Division of Vital Statistics, Mortality Data Table Page 1 of 147

Division of Vital Statistics, Mortality Data Table page 1 of 147 Table I–1. Search terms to identify drugs mentioned in electronic death certificate literal text and associated principal variant, Version 06-30-2015 Spreadsheet version available from: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Publications/NVSR/65_09/Table01.xlsx. Search term Principal variant A PRAZOLAM ALPRAZOLAM ABACAVIR ABACAVIR ABARELIX ABARELIX ABATACEPT ABATACEPT ABCIXIMAB ABCIXIMAB ABILIFY ARIPIPRAZOLE ABIRATERONE ABIRATERONE ABOBOTULINUMTOXINA ABOBOTULINUMTOXINA ABSTRAL FENTANYL ACAMPROSATE ACAMPROSATE ACARBOSE ACARBOSE ACDETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACEBUTOLOL ACEBUTOLOL ACEPROMAZINE ACEPROMAZINE ACETAMINOP ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETIC ACID ACETIC ACID ACETOHEXAMIDE ACETOHEXAMIDE ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETOMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETONE ACETONE ACETOPHENAZINE ACETOPHENAZINE ACETYL MORPHINE HEROIN ACETYLCARBROMAL ACETYLCARBROMAL ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLSALICYCLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACITRETIN ACITRETIN ACRIFLAVINE ACRIFLAVINE ACRIVASTINE ACRIVASTINE ACTIQ FENTANYL ACYCLOVIR ACYCLOVIR ADALIMUMAB ADALIMUMAB ADANON METHADONE ADAPALENE ADAPALENE ADDERALL AMPHETAMINE DEXTROAMPHETAMINE ADEFOVIR ADEFOVIR AFATINIB AFATINIB U.S. Department of Health and Human Services · Centers for Disease Control and Prevention · National Center for Health -

Synthesis and DFT Computational Calculations

1,5-Dichloroethanoanthracene Derivatives as Antidepressant Maprotiline Analogues: Synthesis and DFT Computational Calculations Mujeeb Sultan ( [email protected] ) King Saud University Renjith Raveendran Pillai Central Polytechnic Eman Alzahrani Taif university Research Article Keywords: 1,5-dichloroethanoanthracene, Diels–Alder reaction, Wittig reaction, olenic hydrogenation, maprotiline analogue, DFT Posted Date: May 17th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-515953/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract The chlorinated tetracyclic 1,5-dichloro-9,10-dihydro-9,10-ethanoanthracen-12-yl)-N-methylmethanamine 1, a maprotiline analogue, has been synthesized via reduction and Diels–Alder reaction followed by reductive amination of Aldehyde 2. Density Functional Theory calculations were performed to identify the possible isomers of the intermediate compound aldehyde 2, these calculations were in a good agreement with experimental result where aldehyde 2 could exist in three isomers with comparable energies. In addition, the side chain of this aldehyde 2 was extended via Wittig reaction to obtain the unsaturated ester 5 that subjected to selective olenic catalytic hydrogenation to obtain the corresponding saturated ester 6. 1D-NMR (DEPT) and 2D-NMR (HSQC, DQF-COSY) techniques were recruited for structural elucidation in addition to HRMS. Introduction anthracenes are simply and eciently incorporated into several organic reaction and proved to have a wide range of industrial applications such as in uorescent sensor [1, 2], laser dyes [3] and supramolecular assemblies [4, 5]. Their application in the pharmaceutical agents is another interesting eld. From the organic synthesis point of view, 1,5-dichloroanthracene was functionalized through Kumada coupling to access a series of 1,5- functionalized anthracenes [6]. -

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2004) -- Supplement 1 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2004) -- Supplement 1 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2004) -- Supplement 1 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACEXAMIC ACID 57-08-9 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACICLOVIR 59277-89-3 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ACOXATRINE 748-44-7 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ACREOZAST 123548-56-1 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ACRIDOREX 47487-22-9 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7