Improving Unit Cohesion I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Leadership Roles

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Leadership Roles “Move up through Ranks, Positions, and Experiences” L3/A: Leadership Roles at the School Level Agenda A1. Introduction to Leadership Roles and Responsibilities A2. Assistant Squad Leader and Guidon Bearer A3. Squad Leader A4. Platoon Sergeant A5. Platoon Leader A6. First Sergeant Agenda A7. Company Executive Officer A8. Company Commander A9. S1: Administration and Personnel A10.S2: Safety and Security A11.S3: Training and Operations A12.S4: Supply and Logistics Agenda A13. S5: Civic, Public and Military Relations A14. S6: Communications and IT A15. Battalion Executive Officer (XO) A16. Battalion Command Sergeant Major (CSM) A17. Battalion Commander (CO) INTRODUCTION TO LEADERSHIP ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES A1. Introduction to Leadership Roles and Responsibilities Leadership Roles at the School Level OBJECTIVES Cadets will be prepared to work within the structure of the cadet battalion or brigade, and serve successfully in leadership positions within the California Cadet Corps. Plan of Action Describe the role and responsibilities of the cadet leadership position in California Cadet Corps Battalions: Introduction to Leadership Roles and Responsibilities. Essential Question: How does the CACC develop a leader? Introduction to Leadership Roles and Responsibilities • CACC’s primary objective: Teaching Leadership • Leadership curriculum standard emphasizes: – Military knowledge – Citizenship and patriotism – Academic Excellence – Health and fitness Introduction to Leadership Roles and Responsibilities -

The Squad Leader Makes the Difference

The Squad Leader Makes the Difference Readings on Combat at the Squad Level Volume I Lieutenant M.M. Obalde and Lieutenant A.M. Otero United States Marine Corps Marine Corps Warfighting Lab Marine Corps Combat Development Command Quantico, Virginia 22134 August 1998 1 United States Marine Corps Marine Corps Warfighting Lab Marine Corps Combat Development Command Quantico, Virginia 22134 May 1998 FOREWORD In combat, the actions of individual leaders affect the outcome of the entire battle. Squad leaders make decisions and take actions which can affect the operational and strategic levels of war. Well-trained squad leaders play an important role as combat decisionmakers on the battlefield. Leaders who show initiative, judgment, and courage will achieve decisive results not only at the squad level, but in the broader context of the battle. Without competent squad leaders, capable of carrying out a commander’s intent, even the best plans are doomed to failure. This publication illustrates how bold, imaginative squad leaders impact the outcome of a battle or campaign. The historical examples here represent some of the cases in which squad leaders were able to change the course of history. In each case, the squad leader had to make a quick decision without direct orders, act independently, and accept responsibility for the results. Short lessons are presented at the end of each story. These lessons should help you realize how important your decisions are to your Marines and your commander. In combat, you must think beyond the squad level. You must develop opportunities for your commander to exploit. Your every action must support your commander’s intent. -

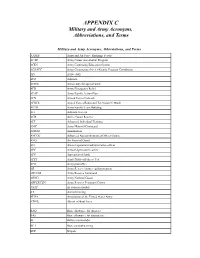

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad

FM 7-8 Table of Contents RDL Document Download Homepage Information Instructions *FM 7-8 FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS NO. 7-8 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 22 April 1992 FM 7-8 INFANTRY RIFLE PLATOON AND SQUAD IMPORTANT U.S. Army Infantry School Statement on U.S. NATIONAL POLICY CONCERNING ANTIPERSONNEL LAND MINES Table of Contents CHANGE 1 Preface http://www.adtdl.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/7-8/toc.htm (1 of 10) [1/9/2002 9:34:30 AM] FM 7-8 Table of Contents Chapter 1 - DOCTRINE Section I - Fundamentals 1-1. Mission 1-2. Combat Power 1-3. Leader Skills 1-4. Soldier Skills 1-5. Training Section II - Platoon Operations 1-6. Movement 1-7. Offense 1-8. Defense 1-9. Security Chapter 2 - OPERATIONS Section I - Command and Control 2-1. Mission Tactics 2-2. Troop-Leading Procedure 2-3. Operation Order Format Section II - Security 2-4. Security During Movement http://www.adtdl.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/7-8/toc.htm (2 of 10) [1/9/2002 9:34:30 AM] FM 7-8 Table of Contents 2-5. Security in the Offense 2-6. Security in the Defense Section III - Movement 2-7. Fire Team Formations 2-8. Squad Formations 2-9. Platoon Formations 2-10. Movement Techniques 2-11. Actions at Danger Areas Section IV - Offense 2-12. Movement to Contact 2-13. Deliberate Attack 2-14. Attacks During Limited Visibility Section V - Defense 2-15. Conduct of the Defense 2-16. Security 2-17. -

Supporting Training Strategies for Brigade Combat Teams Using Future Combat Systems (FCS) Technologies

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Arroyo Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Supporting Training Strategies for Brigade Combat Teams Using Future Combat Systems (FCS) Technologies Michael G. -

Military Units Style Contents

Military Units Style - Colors Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Blue Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 1 Military Units Style - Fill Symbols Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 2 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols à Infantry Soldier  Helicopter - AH Apache Å Missile Launcher Æ Frigate Ê Generic Tank Ç Destroyer Ë Enemy Tank È Submarine SSBN Ì B-2 Stealth É Submarine Attack Ó F-14 Tomcat À Torpedo Ô Fighter ß Explosion Õ FA-18 ! Unit Ö F-5 " Headquarters Unit Ù Fighter # Logistics/Admin Installation Ú Fighter $ Theater Ü Generic Fighter % Corps Ò E-3 AWACS & Supply unit Ï Helicopter - CH-46 Chinook ' Squad Ð Helicopter - AH Cobra ( Section/Platoon Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 3 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols ) Platoon/Squadron 8 Infantry Battalion * Company/Battery/Troop 9 Infantry Regiment + Battalion/Squadron : Infantry Brigade , Regiment ; Infantry Division - Brigade < Infantry Corps . Division = Infantry Army / Corps > Infantry Mechanized Squad 0 Army ? Infantry Mechanized Section 1 Infantry @ Infantry Mechanized Platoon 2 Infantry Mechanized A Infantry Mechanized Company 3 Armor B Infantry Mechanized Battalion Company 4 Infantry Squad C Infantry Mechanized Regiment 5 Infantry Section D Infantry Mechanized Brigade 6 Infantry Platoon E Infantry Mechanized Division 7 Infantry Company F Infantry Mechanized Corps Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. -

Unit-Manning in the Us Army

FORGING THE SWORD: UNIT- MANNING IN THE US ARMY Pat Towell FORGING THE SWORD: UNIT-MANNING IN THE US ARMY by Pat Towell Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments September 2004 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) is an independent, nonprofit, public policy research institute established to make clear the inextricable link between near-term and long- range military planning and defense investment strategies. The Center is directed by Dr. Andrew F. Krepinevich and funded by foundations, corporations, government, and individual grants and contributions. This report is one in a series of CSBA analyses on future US military strategy, force structure, operations, and budgets. The author would like to thank the staff of the CSBA for their comments and assistance on this report: Steven Kosiak, Andrew Krepinevich, Christopher Sullivan, Luciana Turner, Michael Vickers, and Barry Watts. He also greatly appreciates comments by John Chapla, Lt. Gen. Robert W. Elton (US Army ret.), Robert Goldich, W. Michael Hix, Maj. Brendan B. McBreen (USMC), Robert S. Rush, Johnathan Shay, Guy L. Siebold, and Col. Paul D. Thornton (US Army), each of whom generously took time to review earlier drafts of the report. The analysis and findings presented here are solely the responsibility of CSBA and the author. 1730 Rhode Island Ave., NW Suite 912 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 331-7990 CONTENTS OVERVIEW................................................................ I CHAPTER 1. THE QUEST FOR STABILIZATION ..................1 The Current System...........................................4 The Road to COHORT.........................................7 Beyond the Cold War.........................................9 How Certain a Future?.....................................12 One More Time................................................15 CHAPTER 2. -

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract mostly from FM 3-21.8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad , but it also includes references from other FMs. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-TC. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. CHAPTER 1 - DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................... 2 CHAPTER 2 - COMMAND AND CONTROL.............................................................. 6 SECTION I – TROOP LEADING PROCEDURES .................................................. 6 SECTION II – RISK MANAGEMENT ..................................................................... 9 SECTION III - ORDERS ........................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 3 – OPERATIONS ..................................................................................... 14 SECTION I – FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION ....................................... 14 SECTION II – RANGE CARDS AND SECTOR SKETCHES ............................. 16 SECTION III - MOVEMENT ................................................................................... 25 SECTION IV - COMMUNICATION ....................................................................... 27 SECTION V - REPORTS ......................................................................................... -

Small Unit Movement Formations

Enabling Learning Objective Show-Me GOLD Program ELO 1 Show-Me GOLD Show-Me GOLD ACTION: Determine the purpose of Fire Team formations. CONDITION: Given an instructor and prescribed manuals. STANDARD: IAW 3-0 Unified Land Operations, FM 3-21.8 The Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad, and FM 3-21.10 The Infantry Rifle Company. Achieve a minimum passing score of 80% in overall testing. “Forever Forward” “Forever Forward” TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVE Show-Me GOLD Show-Me GOLD ACTION: Identify Movement Formations and Techniques . CONDITION: Given an instructor, classroom, and SMALL UNIT MOVEMENT prescribed manuals. FORMATIONS STANDARD: IAW ADRP 3-0 Unified Land Operations, FM 3-21.8 The Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad, and FM 3-21.10 The Infantry Rifle Company. Achieve a minimum passing score of 80% in overall testing. “Forever Forward” “Forever Forward” THE FIRE TEAM COMPONENT Show-Me GOLD Show-Me GOLD THE INFANTRYMAN: Supervises, leads, or serves as a member of an infantry activity that employs individual or crew served weapons in support of offensive and defensive combat operations Most infantry operates in "Fire Teams" of three to four men, with two or three such teams to squad. When attacking, each man in the team has a specific job. 1) Fire team leaders control the fire of their soldiers by using standard fire commands (initial and supplemental) containing the following elements: Alert, Direction, Description, Range, Method of fire (manipulation and rate of fire), and command to commence firing 2) The Automatic Rifleman (or light machine gunner) tries to pin the enemy down. 3) The Grenadier (armed, usually, with an M203 or the equivalent) does two things: helps the automatic rifleman isolate the enemy position, and looks for an opening to shoot a RISK ASSESSMENT grenade at it. -

FM 6-22 Leader Development

This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (https://armypubs.us.army.mil/doctrine/index.html). To receive publishing updates, please subscribe at http://www.apd.army.mil/AdminPubs/new_subscribe.asp. *FM 6-22 Field Manual Headquarters No. 6-22 Department of the Army Washington, DC, -XQH Leader Development Contents Page PREFACE............................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .....................................Y INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... vi Chapter 1 LEADER DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................ 1-1 Tenets of Army Leader Development ................................................................. 1-1 The Challenge for Leader Development ............................................................ 1-2 Leadership Requirements .................................................................................. 1-3 Cohesive and Effective Teams ...........................................................................1-5 Growth Across Levels of Leadership and by Cohorts ........................................ 1-7 Transitions across Organizational Levels ........................................................... 1-8 Chapter 2 PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................ 2-1 Unit Leader Development Programs ................................................................. -

Infantry Rifle Platoon & Squad (FM 7-8)

FM 7-8 INFANTRY RIFLE PLATOON AND SQUAD HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION – Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. FM 7-8 C1 HEADQUARTERS CHANGE 1 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 1 March 2001 1. Change FM 7-8, dated 22 April 1992, as follows: REMOVE OLD PAGES INSERT NEW PAGES None 6-1 through 6-66 2. A star (*) marks new or changed material. 3. File this transmittal sheet in front of the publication. This Publication is available on the General Dennis J. Reimer Training And Doctrine Digital Library www.adtdl.army.mil DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTIONApproved for public release; distribution is unlimited. C1, fm 7-8 1 March 2001 By Order of the Secretary of the Army: ERIC K. SHINSEKI General, United States Army Chief of Staff Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army 0104302 DISTRIBUTION: Active Army, Army National Guard, and U.S. Army Reserve: To be distributed in accordance with the initial distribution number 110782, requirements for FM 7-8. FM 7-8 PREFACE This manual provides doctrine, tactics, techniques and procedures on how infantry rifle platoons and squads fight. Infantry rifle platoons and squads include infantry, airborne, air assault, ranger, and light infantry platoons and squads. This manual supersedes FM 7-8, Infantry Platoon and Squad dated April 1981, as well as FM 7-70, The Light In fantry platoon and Squad dated September 1986, and is aligned with the Army’s AirLand Battle doctrine. It is not intended to be a stand-alone publica- tion. An understanding of FM 7-10, The Infantry Rifle Company, and FM 7-20, The Infantry Battalion, is essential. -

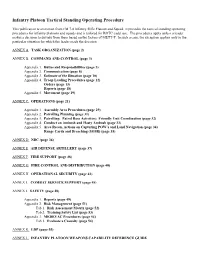

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract from FM 7-8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-T. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. ANNEX A. TASK ORGANIZATION (page 2) ANNEX B. COMMAND AND CONTROL (page 3) Appendix 1. Duties and Responsibilities (page 5) Appendix 2. Communication (page 8) Appendix 3. Estimate of the Situation (page 10) Appendix 4. Troop Leading Procedures (page 12) Orders (page 13) Reports (page 18) Appendix 5. Movement (page 19) ANNEX C. OPERATIONS (page 21) Appendix 1. Assembly Area Procedures (page 29) Appendix 2. Patrolling Planning (page 31) Appendix 3. Patrolling: Patrol Base Activities; Friendly Unit Coordination (page 32) Appendix 4. Conduct an Ambush and Hasty Ambush (page 33) Appendix 5. Area Recon, Actions on Capturing POW’s and Land Navigation (page 34) Range Cards and Breaching (SOSR) (page 35) ANNEX D. NBC (page 36) ANNEX E. AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY (page 37) ANNEX F. FIRE SUPPORT (page 38) ANNEX G. FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION (page 40) ANNEX H OPERATIONAL SECURITY (page 43) ANNEX I. COMBAT SERVICE SUPPORT (page 45) ANNEX J. SAFETY (page 48) Appendix 1. Reports (page 49) Appendix 2. Risk Management (page 51) Tab 1. Risk Assessment Matrix (page 52) Tab 2. Training Safety List (page 53) Appendix 3.