A Critique of the Transformative Fair Use Test in Practice and the Need for a New Music Fair Use Exception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swedish Pop Mafia: How a Culturally Conservative Effort in the 1940S Backfired to Create the Greatest Engine of Pop Music in the World

Swedish Pop Mafia: How a culturally conservative effort in the 1940s backfired to create the greatest engine of pop music in the world BY WHET MOSER • March 24, 2014 • At some point over the last 15 years—sometime, say, between the 1999 release of “I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys and last year’s “Roar” by Katy Perry—it became an inescapable fact that if you want to understand American pop music, you pretty much have to understand Sweden. Songwriters and producers from Stockholm have buttressed the careers of Lady Gaga, Madonna, Usher, Avril Lavigne, Britney Spears, The Backstreet Boys, Pitbull, Taylor Swift, One Direction, Maroon 5, Kelly Clarkson, and any number of other artists you’ve probably listened to while dancing, shopping, making out, or waiting on hold over the past decade. (And it’s not just American pop music that has Scandinavian fingerprints all over it: When Azerbaijan won the Eurovision contest in a 2011 upset, they did it with a song written for them by two Swedes.) If Americans are aware of this phenomenon, it is probably because they’ve heard about the legendary Swedish producer and songwriter Max Martin. There are any number of ways to express Martin’s ubiquity, but here’s one: From 2010 to 2011, the pop idol Katy Perry spent an unprecedented 69 consecutive weeks in the Billboard top 10, surpassing the previous record-holder, the 1990s Swedish group Ace of Base, by four months. But the milestone was far more of a testament to Martin’s staying power than Perry’s: Not only did he help produce and write all but one of Perry’s record- breaking string of hits, but he began his career as a producer for Ace of Base. -

Rush Rush Debbie Harry Mp3 Download Free

rush rush debbie harry mp3 download free Télécharger Debbie Harry - Rush Rush (Extended Version) Download and listen online Rush, Rush Extended Version by Debbie Harry. Genre - Synthpop. Duration 04:44. Format mp3. Music video. On this page you can download song Debbie Harry - Rush, Rush Extended Version in mp3 and listen online. Synthpop Disco. Debbie Harry. Rush, Rush Special Extended Remix. Rush Rush is a song by American singer Debbie Harry. Released as a single in 1983, it is taken from the soundtrack album of the film Scarface 1983. Rush Rush was the first single Harry released after Blondie broke up in 1982, and was one of the several projects she worked on in between her first and second solo albums. It was Harry's second collaboration with Italian producer Giorgio Moroder, the first being Blondie's 1980 number-one hit Call Me from the 1980 movie American Gigolo. The song. Eurythmics - Love Is A Stranger Ultra Traxx 12 Mix Version - Продолжительность: 9: about Rush, Rush Extended Version from Deborah Harry's Rush Rush Special Extended Remix and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists. A new version of is available, to keep everything running smoothly, please reload the site. Deborah Harry. Rush, Rush Extended Version. Love this track. Deborah Harry - Rush Rush 1983 Scarface Soundtrack produced by Giorgio Moroder. Debbie Harry Giorgio Moroder Rush Scarface Soundtrack Score Hi-NRG New Wave Electronic 80s 1983 Tony Montana film Brian De Palma song Yeyo original music Al Pacino Blondie Extended Mix Pop. 2020 40th Anniversary. The Studio Albums 1989-2007. Vapor Trails. -

November 12, 1981 Happy 434-2282

• - I \ (.1 59 James Madison University Thursday, November 12, MlHl MM \n :<■ New hoard may form under SGA By I'AMMV MOONF.Y Permission in form a Community Relations Board was graiitwl {0 tne student Government Association at a meeting with university ad- ministrators Friday Robert Vaughn, head of the University Farm sub committee, presented university community problems his subcommittee hid studied and the solutions it deemed feasible. The i (immunity Relations Board will handle bad checks, zoning problems. T'niversity Farm grievances and other community problems in- ■.diving James Madison University students The board would be like the liversity Program Board - reporting to.the SGA; but not a committee wnder^it. Vaughn said T~^ The board Should be in operation by- the fall 19K2, Vaughn said * The board will include a Ron Robison I left to right). Patty Edge and Kim Robins wait to be cleared for registration in the Warren Campus Center Ballroom, committee to handle bad I he new computerized system suffered a minor breakdown Tuesday night. See story, page 3. check problems If a merchant receives, a This The JMl soccer team ended its season with . Apartments In Harrisonburg is becoming bad check, he would try to a 2-1 win over University of Baltimore scarce as JMl wants more students to live deposit it again after con- Tuesday. See Sports, page 9. off-campus. See City News, back page. tacting the student If the issue... • • _ j .: check still" is "not paid, the" committee would pa.y the amount of the check tp the merchant. -

Hybrid Gangs and the Hyphy Movement: Crossing the Color Line in Sacramento County

HYBRID GANGS AND THE HYPHY MOVEMENT: CROSSING THE COLOR LINE IN SACRAMENTO COUNTY Antoinette Noel Wood B.S., California State University, Sacramento, 2008 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in CRIMINAL JUSTICE at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2011 © 2011 Antoinette Noel Wood ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii HYBRID GANGS AND THE HYPHY MOVEMENT: CROSSING THE COLOR LINE IN SACRAMENTO COUNTY A Thesis by Antoinette Noel Wood Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dimitri Bogazianos, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Dan Okada, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Antoinette Noel Wood I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ________________ Yvette Farmer, Ph.D. Date Division of Criminal Justice [Thesis Abstract Form] iv [Every thesis or project mustracts for some creative works such as in art or creative writing may vary somewhat, check with your Dept. Advisor.] Abstract of HYBRID GANGS AND THE HYPHY MOVMENT: CROSSING THE COLOR LINE IN SACRAMENTO COUNTY by Antoinette Noel Wood [Use of the next optional as long as te content is supplied.]three headings is Statement of Problem Crips and Bloods-traditional gangs whose mere names conjure up fearful images of violence and destruction-are no longer at the forefront of the gang reality in Sacramento. Instead, influenced by the Bay Area-based rap music subculture of Hyphy, gangs calling themselves "Families," "Mobbs," and "Camps" are believed to be creating a new, hybridized gang culture. -

Fall Winter 2020

Fall Winter 2020 Chrome Trench Multi Check/Camel-Check Sunday Girl Dress / Cognac Debbie Shirt / White Debbie Shirt / Beige Rapture Trench Faux Leather/Black Rapture Wool Coat Faux Leather Collar / Olive Laura Silk Blouse / Avocado Debbie Skirt / Moss Green Sunday Girl Merino Wool Sweater / Grey Melange Oblique Pleated Skirt Faux Leather / Black Small Chrome Clutch Bag / Silver Rapture Trench Coat / Ecru Rapture Wool Coat Faux Leather Collar/Powder Pink Chrome Wool Coat / Otmmeal Melange Chrome Coat Grey Mix / Grey Call Me Wool Coat / Butter Call Me Wool Coat / Tobacco Brown Rockbird Coat / Black Kookoo Trench Coat / Black Vittoria Trench Coat / Cold Beige Full Check Trench Coat / Check Vittoria Suede Trench Coat / Coffee Brown Kookoo Trench Coat / Dark Green Sunday Girl Dress Vanilla Yellow Heart of Glass Coat / Black Denis Coat / Beige Four Pockets Jacket / Chalk The Female Touch Skinny Pants / Burgundy Four Pockets Jacket / Brown Oblique Pleated Skirt Faux Leather / Brown Furry Hoodie Coat / Grey Sunday Girl Pants / Brown Iggy Pants / Black Sunday Girl Merino Wool Sweater / Cream Rock Bird Skirt Merino Wool Pullover with Scarf / Buttermilk Pleated Denim Skirt / Blue Merino Wool Pullover with Scarf / Sand Melange Merino Wool Pullover with Scarf / Oatmeal Melange Offender Jacket / Black Backfred Blazer Coat / Black Backfred Blazer Coat / Vanilla Yellow Backfred Blazer Coat Suede / Moss Green Dumb and Blonde Fur Coat / grey Sunday Girl Pants / Black Lilac Faux Fur Coat Blondie Fur Coat / Brown The Female Touch Top / Black Carla Reversible -

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What You Are About to Read Is the Book of the Blog of the Facebook Project I Started When My Dad Died in 2019

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What you are about to read is the book of the blog of the Facebook project I started when my dad died in 2019. It also happens to be many more things: a diary, a commentary on contemporaneous events, a series of stories, lectures, and diatribes on politics, religion, art, business, philosophy, and pop culture, all in the mostly daily publishing of 365 essays, ostensibly about an album, but really just what spewed from my brain while listening to an album. I finished the last essay on June 19, 2020 and began putting it into book from. The hyperlinked but typo rich version of these essays is available at: https://albumsforeternity.blogspot.com/ Thank you for reading, I hope you find it enjoyable, possibly even entertaining. bottleofbeef.com exists, why not give it a visit? Have an album you want me to review? Want to give feedback or converse about something? Send your own wordy words to [email protected] , and I will most likely reply. Unless you’re being a jerk. © Bottle of Beef 2020, all rights reserved. Welcome to my record collection. This is a book about my love of listening to albums. It started off as a nightly perusal of my dad's record collection (which sadly became mine) on my personal Facebook page. Over the ensuing months it became quite an enjoyable process of simply ranting about what I think is a real art form, the album. It exists in three forms: nightly posts on Facebook, a chronologically maintained blog that is still ongoing (though less frequent), and now this book. -

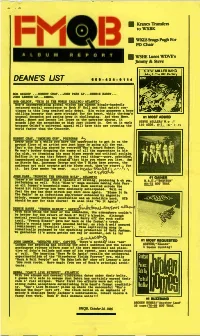

Deane's List 6 0 9 - 4 2 4 - 9 1 1 4

Kranes Transfers to WXRK • NIVKLS Snags Pugh For PD Chair • WSHE Lures WDVE's Jimmy & Steve STEVE MILLER BAND Living In The 20th Century DEANE'S LIST 6 0 9 - 4 2 4 - 9 1 1 4 BOB GELDOF ...ROBERT CRAY...JOHN PARR LP...DEBBIE HARRY... JOHN LENNON LP. ..ZEBRA. BOB GELDOF, "THIS IS THE WORLD CALLING," ATLANTIC Bob's uncompromising global vision has almcst single-handedly returned social conscience to Rock N' Roll and that spirit con- tinues in this long awaited solo debut. His voice posseses a bone chilling honesty that goes straight for the heart, while the song's unusual dynamics and pacing keep it challenging. And when Mmes. #1 MOST ADDED McKee, Moyet and Lennox let loose on the operator chorus, it sounds like the seraphims on high just joined in. Get on it early STEVE MILLER/"World" because Geldof's universal appeal will have this one crossing the 110 ADDS, d-17 HOT TRAX world faster than the Concorde. ROBERT CRAY, "SMOKING GUN", POLYGRAM Every once in a while you have the op rtunity to get in on the ground floor of an artist you just know is going all the way. That's the feeling shared by everyone who's heard Robert Cray. We won't bother dropping the names of all the superstars in his fan club, or itemizing his many blues awards and critical acclaim. Suffice it to say that Robert is the real thing---pure, unbridled, impassioned playing and singing that hits you where you live. And as Stevie Ray, Lonesome George and the T Birds have proven, the audience not only accepts gritty blues rock, they're starvi g for it. -

Debbie Harry in Love with Love Mp3, Flac, Wma

Debbie Harry In Love With Love mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: In Love With Love Country: US Released: 1986 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1170 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1904 mb WMA version RAR size: 1617 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 321 Other Formats: DXD MOD AIFF ASF VOC MP4 DMF Tracklist Hide Credits In Love With Love (Extended Version) A Mixed By – Pete HammondProducer – Seth Justman, Stock, Aitken & WatermanWritten-By 7:17 – Chris Stein, Debbie Harry* Feel The Spin B1 Arranged By – Tony C.Producer – John "Jellybean" BenitezWritten-By – Debbie Harry*, 6:50 Jellybean*, Tony C. French Kissin' In The USA (French Version) B2 5:10 Producer, Arranged By – Seth JustmanWritten-By – Chuck Lorre Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Ariola Eurodisc GmbH Phonographic Copyright (p) – BMG Ariola München GmbH Copyright (c) – Chrysalis Records Ltd. Distributed By – RCA/Ariola-Ariola/RCA Credits Design – John Pasche Photography By – Brian Aris Notes Printed in Germany. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4 007196 090972 Rights Society: GEMA STEMRA BIEM Label Code: LC 1626 Other (Distribution Code D:): 213 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Debbie In Love With Love (7", Geffen 7-28476 7-28476 US 1986 Harry* Styrene) Records Debbie In Love With Love Geffen 0-20687 0-20687 US 1987 Harry* (12", Maxi) Records Debbie In Love With Love CHS 448 Chrysalis CHS 448 Italy 1987 Harry* (7") Debbie In Love With Love CHS 12 3128 Chrysalis CHS 12 3128 UK 1987 Harry* (12", Single) -

"What's Going On": Motown and the Civil Rights Movement

"What's Going On": Motown and the Civil Rights Movement Author: Anika Keys Boyce Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/590 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. 1 “What’s Going On”1: Motown and the Civil Rights Movement Anika Keys Boyce May 7, 2008 1 Marvin Gaye, “What’s Going On,” What’s Going On (Remastered). (Motown Records, 2002). 2 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1: The Man and the Dream……………………………………………………...12 Chapter 2 : The Sound of Young America……………………………………………….27 Chapter 3: Achieving “Cross over” Through Civil Rights Principles…………………...45 Chapter 4: Race, Motown and Music……………………………………………………62 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….77 3 Introduction Based in 1960s Detroit, the Motown Record Company established itself and thrived as an independently run and successful African American business. Amidst humble origins in a two-story house outside of which Berry Gordy hung the sign, “Hitsville USA,” Motown encouraged America’s youth, urging them to look beyond racial divides and to simply sing and dance together in a time where the theme of unity was becoming increasingly important. Producing legends such as Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Four Tops, Martha Reeves, Gladys Knight, and the Jackson Five, Motown truly created a new sound for the youth of America and helped shape the 1960s. Competing with the “British Invasion” and “the Protest Movement,” in 1960s music, Motown is often said to have had little or no impact on the political and social revolution of the time because Motown did not produce “message 4 music.” The 2006 film, Dreamgirls even depicts Gordy and Motown as hypocrites and race traitors. -

Vol. 26 No. 6, October 29, 1981

Park Place gets long-awaited hot water by Bill Travers owner of Park Place. "I was not notified we would convert to gas," Pavelco said. of by Regini. Gas shipments will be paid about the problem until a week after," said "The electric water heaters are the most ex A new.gas heater >as installed in the for by Marist, as is done with electric bills Regini. "I sent my electrician out to check pensive to use and the least efficient. Gas of the other heaters. Park Place dormitories on Oct. 23, ending the situation. He reported back to me that will be-cheaper, but most importantly it' three weeks without hot water for ten all fuses were, working, which meant that will be more efficient for the students." "What upset me the most was that the residents. '•'':"'• - the hot water heater should have been Installation of the new gas system started students were kept in the dark throughout "It's about time," said a" relieved Sue working also." on Oct. 23, 16 days after the problem the whole period," said Jeanne Lc Goldfeder, resident of Park Place. "It arose. "I was under the impression that the Gloahec, resident of Park Place. "We had should not have taken as long as it did for it - After more than a week without hot heater would be installed while the students no idea when we would get hot water or to be fixed. It's really inconvenient to have water, a reason still had not been found. were on their mid-term break, Seeger said. -

From Blurred Lines to Blurred Law: an Assessment of the Possible Implications of "Williams V

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 28 Issue 1 Article 10 January 2021 From Blurred Lines to Blurred Law: An Assessment of the Possible Implications of "Williams v. Gaye" in Copyright Law Hannah Patton University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Hannah Patton, From Blurred Lines to Blurred Law: An Assessment of the Possible Implications of "Williams v. Gaye" in Copyright Law, 28 J. INTELL. PROP. L. 251 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol28/iss1/10 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Blurred Lines to Blurred Law: An Assessment of the Possible Implications of "Williams v. Gaye" in Copyright Law Cover Page Footnote J.D. Candidate, 2021, University of Georgia School of Law. I would like to thank the Editorial and Executive Boards of the Journal of Intellectual Property Law for all of their help, as well as Professor Stephen Wolfson and friend Ian Kecskes for inspiring this Note’s entertainment theme. I dedicate this Note to my loving parents, Steve and Amy Patton. Thank you for your constant support and encouragement throughout my life. I would also like to dedicate this Note to my college professor and mentor, Dr. -

Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992

Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 By Felicia Angeja Viator A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Leon F. Litwack, Co-Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Scott Saul Fall 2012 Abstract Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 by Felicia Angeja Viator Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Leon F. Litwack, Co-Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Co-Chair “Gangster Boogie” details the early development of hip-hop music in Los Angeles, a city that, in the 1980s, the international press labeled the “murder capital of the U.S.” The rap music most associated with the region, coined “gangsta rap,” has been regarded by scholars, cultural critics, and audiences alike as a tabloid distortion of East Coast hip-hop. The dissertation shows that this uniquely provocative genre of hip-hop was forged by Los Angeles area youth as a tool for challenging civic authorities, asserting regional pride, and exploiting the nation’s growing fascination with the ghetto underworld. Those who fashioned themselves “gangsta rappers” harnessed what was markedly difficult about life in black Los Angeles from the early 1970s through the Reagan Era––rising unemployment, project living, crime, violence, drugs, gangs, and the ever-increasing problem of police harassment––to create what would become the benchmark for contemporary hip-hop music. My central argument is that this music, because of the social, political, and economic circumstances from which it emerged, became a vehicle for underclass empowerment during the Reagan Era.