1 Wall Street's Content Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 19-275 Released: April 10, 2019 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS TO TRANSFER CONTROL OF NBI HOLDINGS, LLC, AND COX ENTERPRISES, INC., TO TERRIER MEDIA BUYER, INC., AND PERMIT-BUT-DISCLOSE EX PARTE STATUS FOR THE PROCEEDING MB Docket No. 19-98 Petition to Deny Date: May 10, 2019 Opposition Date: May 28, 2019 Reply Date: June 4, 2019 On March 4, 2019, Terrier Media Buyer, Inc. (Terrier Media), NBI Holdings, LLC (Northwest), and Cox Enterprises, Inc. (Cox) (jointly, the Applicants) filed applications with the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) seeking consent to the transfer of control of Commission licenses through two separate transactions.1 First, Terrier Media and Northwest seek consent for Terrier Media to acquire companies owned by Northwest holding the licenses of full-power broadcast television stations, low-power television stations, and TV translator stations (the Northwest Applications). Next, Terrier Media and Cox seek consent for Terrier Media to acquire companies owned by Cox holding the licenses of full-power broadcast television stations, low-power television stations, TV translator stations, and radio stations (the Cox Applications and, jointly with the NBI Applications, the Applications).2 Pursuant to a Purchase Agreement between Terrier Media and the equity holders of Northwest dated February 14, 2019, Terrier Media would acquire 100% of the interest in Northwest.3 Pursuant to a separate Purchase Agreement between Terrier Media and Cox and affiliates of Cox, Terrier Media would acquire the companies owning all of Cox’s television stations and the licenses and other assets of four of Cox’s radio stations.4 The Applicants propose that Terrier Media, which is a newly created company, will become the 100% indirect parent of the licensees listed in the Attachment. -

Apollo Global Management Appoints Tetsuji Okamoto to Head Private Equity Business in Japan

Apollo Global Management Appoints Tetsuji Okamoto to Head Private Equity Business in Japan NEW YORK, NY – December 5, 2019 – Apollo Global Management, Inc. (NYSE: APO) (together with its consolidated subsidiaries, “Apollo”) today announced the appointment of Tetsuji Okamoto as a Partner, Head of Japan, leading Apollo Private Equity’s efforts in Japan. Mr. Okamoto will play a lead role in building Apollo’s Private Equity business in Japan, including originating and executing deals and identifying cross-platform opportunities. He will report to Steve Martinez, Senior Partner, Head of Asia Pacific, and will begin in this newly created role on December 9, 2019. “This appointment and the new role we’ve created is a reflection of the importance we place on Japan and the opportunities we see in the wider region for growth and diversification,” Apollo’s Co-Presidents, Scott Kleinman and James Zelter said in a joint statement. “Tetsuji’s addition signals Apollo’s meaningful long-term commitment to expanding its presence in the Japanese market, which we view as a key area of investment focus as we seek to build value and drive growth for Japanese corporations and our investors and limited partners,” Mr. Martinez added. Mr. Okamoto, 39, brings more than 17 years of industry experience to the Apollo platform and the Private Equity investing team. Most recently, Mr. Okamoto was a Managing Director at Bain Capital, where he was a member of the Asia Pacific Private Equity team for eleven years, responsible for overseeing execution processes for new deals and existing portfolio companies in Japan. At Bain Capital he was also a leader on the Capital Markets team covering Asia. -

Saban Acquires Leading Lifestyle Company Paul Frank Industries

Saban Acquires Leading Lifestyle Company Paul Frank Industries Saban Brands To Manage Paul Frank Brand and Global Licensing Program Company Also Plans To Develop Content and Media Opportunities Based On World-Famous Characters, Including The Iconic Monkey, Julius LOS ANGELES, CA. (August 17, 2010) – Saban Capital Group, Inc. announced today that its affiliate has acquired renowned lifestyle company Paul Frank Industries (PFI) including all company assets and intellectual property, an extensive design portfolio including more than 150 characters, headlined by the omnipresent monkey Julius. Saban Brands, an affiliate of Saban Capital Group, Inc., will be responsible for the management of the company’s business strategy moving forward, while creative operations will remain based in PFI’s current headquarters in Costa Mesa, California. PFI marks the second acquisition, in the $500 million fund for Saban Brands, which was created to manage and license entertainment properties and consumer brands across media and consumer platforms throughout the world. The first property, the Power Rangers franchise, was announced in early May. The company will continue to acquire additional brands going forward. In conjunction with the acquisition, Saban Brands also has announced plans to support the Paul Frank brand with new content and media strategies incorporating the Paul Frank characters. The property will be showcased at Brand Licensing Europe in September. “Paul Frank Industries is one of the world’s leading lifestyle properties and we are delighted to add it to our stable of brands,” said Haim Saban, chairman and chief executive officer, Saban Capital Group, Inc. “Paul Frank Industries has established a unique image that resonates with a wide variety of consumers and we look forward to building on its global success.” “This acquisition ties into Saban’s strategy of building a portfolio of compelling global properties that touch consumers’ lives through strategic licensing partnerships,” stated Elie Dekel, President of Saban Brands. -

Brokeback Mountain'' and the Oscars I Lesbijek

''Americans Don't Want Cowboys to Be Gay:'' Amerykanów, nawet wśród najbardziej liberalnych heteroseksualnych popleczników równouprawnienia gejów ''Brokeback Mountain'' and the Oscars i lesbijek. ______________________ William Glass When Crash (2005) was the surprise best picture winner at the 2006 Oscar ceremony, a variety of explanations were offered for the ("Amerykanie nie chcą kowbojów-gejów". "Brokeback Moutain" upset over the pre-Oscar favorite, Brokeback Mountain (2005). i Oskary) Some suggested a Brokeback backlash occurred; that is, that Brokeback Mountain, which had won critical praise and awards from STRESZCZENIE: Kiedy w 2006 roku Crash zdobył the time of its release and was the highest grossing picture of the five niespodziewanie Oskara za najlepszy film roku, pojawiło się wiele nominated, had worn out its welcome with the Academy voters. prób wyjaśnienia porażki, jaką poniósł przedoskarowy faworyt, Others argued that the Academy got it right: Crash was the superior Brokeback Mountain. Celem tego eseju nie jest porównanie film. A few mentioned the massive marketing campaign by the walorów artystycznych tych dwóch filmów, ani też ustalenie, czy studio on behalf of Crash, swamping the members of the Academy odrzucenie obrazu Brokeback Mountain przez Akademię with free copies of the DVD. Another popular explanation was that motywowane było ukrytą homofobią, ale raczej odpowiedź na since Crash was set in Los Angeles and since most Academy pytanie, czego można dowiedzieć się o powszechnych postawach members live in Los Angeles, the voters chose the movie that i wyobrażeniach dotyczących miejsca gejów i lesbijek reflected their experiences.[1] Larry McMurtry, one of the w społeczeństwie amerykańskim na podstawie dyskusji na temat screenwriters for Brokeback Mountain, offered two of the more zwycięstwa filmu Crash, która toczyła się w Internecie, na blogach insightful explanations, both of which turned on prejudice. -

Lionsgate and Saban Brands Partner for Power Rangers Live Action Feature Film

LIONSGATE AND SABAN BRANDS PARTNER FOR POWER RANGERS LIVE ACTION FEATURE FILM SANTA MONICA, CA, May 7, 2014 – Lionsgate (NYSE: LGF), a leading global entertainment company, and Saban Brands, a strategic brand management company that acquires and builds global consumer brands, are partnering to develop and produce an original live action feature film based on the iconic Power Rangers property, it was announced today by creator of Power Rangers Haim Saban and Lionsgate Chief Executive Officer Jon Feltheimer. The announcement marks another step in Lionsgate’s continued commitment to build a broad portfolio of branded properties and franchises with global appeal. Saban launched Mighty Morphin Power Rangers as a live action television series more than 20 years ago, and the series has been in continuous production ever since. It has subsequently grown into one of the world’s most popular and recognizable brands, with toys, apparel, costumes, video games, DVD’s, comic books and other merchandise. The two companies noted that, with an extensive and extremely devoted worldwide fan base as well as a deep and detailed mythology, the Power Rangers are primed for the big screen. The new film franchise will re-envision the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, a group of high school kids who are infused with unique and cool super powers but must harness and use those powers as a team if they have any hope of saving the world. “Lionsgate is the perfect home for elevating our Power Rangers brand to the next level,” said Saban. “They have the vision, marketing prowess and incredible track record in launching breakthrough hits from The Hunger Games to Twilight and Divergent. -

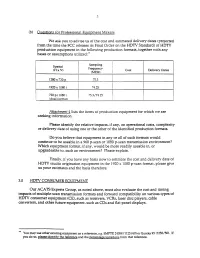

(B) Questions for Professional EQ,Uipment Makers We Ask You to Advise Us of the Cost and Estimated Delivery Dates (Projected

(b) Questions for Professional EQ,uipment Makers We ask you to advise us of the cost and estimated delivery dates (projected from the time the FCC releases its Final Qrder on the HDTV Standard) of HDTV production equipment in the following production formats, together with any bases or assumptions utilized:'· Sampling Spatial (HxV) Frequency Cost Delivery Dates (MHz) I 1280 x 720 p 75.3 1920 x 1080 i 74.25 720 p/1080 i 75.3/74.25 I (dual format) i Attachment 4 lists the items of production equipment for which we are seeking infonnation. Please identify the relative impacts, if any, on operational costs, complexity or delivery date of using one or the other of the identified production formats. Do you believe that equipment in any or all of such formats would continue to be useable in a 960 p-scan or 1080 p-scan transmission environment? Which equipment format, if any, would be more readily useable in, or upgradeable to, such an environment? Please explain. Finally, if you have any basis now to estimate the cost and delivery date of HDTV studio origination equipment in the 1920 x 1080 p-scan format, please give us your estimates and the basis therefore. 3.0 HDTV CONSUMER EQUIPMENT Our ACATS Experts Group, as noted above, must also evaluate the cost and timing impacts of multiple-scan transmission formats and forward compatibility on various types of HDTV consumer equipment (CE), such as receivers, VCRs, laser disc players, cable converters, and other future eqUipment, such as CDs and flat panel displays. -

Download Report (PDF)

Innovation We strive to create opportunities with new approaches and resources. Our Guiding Integrity Principles We do the right thing for the right reasons. Our culture is defined by six core values. They are the key to our storied legacy and the guide to our daily business decisions. Excellence We pride ourselves on the quality of our work, and we seek to exceed expectations. Entrepreneurship We believe that great organizations are built by employing and partnering with the best and brightest people. Talent We believe in fostering individual creativity and a sense of ownership. Stewardship We are dedicated to safeguarding the capital and trust of our clients, and advancing their best interests. A Letter From Managing Partner Peter Lawson-Johnston II At the time of writing this letter, the world is enduring a health crisis while the United States is undergoing a self-examination of societal inequities, both of which are challenging our preconceived notions of where and how we work, learn, worship, and most importantly, how we connect with each other as a community. This is our fourth annual Impact Report that documents our achievements and values as they relate to contributing to the communities where we live and work. But how do you assess your impact on the world, as a business, and as a corporate citizen, when the world seemingly has fundamentally changed? A crisis of this scale is remarkable in how it forces one to focus simultaneously on the uncertainty of today as well as the uncertainty of next year or future decades. Uncertainty can be insidious, and it is easy to withdraw or disengage. -

Emerging Trends in Real Estate®

GREGG GALBRAITH, RED STUDIO GREGG GALBRAITH, NICO MARQUES Emerging Trends in Real Estate® United States and Canada 2017 Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2017 A publication from: Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2017 Contents 3 Chapter 1 Playing for Advantage, Guarding 68 Chapter 5 Emerging Trends in Canadian the Flank Real Estate 4 Context: A Kinder, Gentler Real Estate Cycle? 68 More Than Mixed Use, It’s about Building 5 Optionality Communities 6 Transformation through Location Choice 78 Affordability on the Decline 8 Recognizing the Role of the Small 98 Renting for the Long Term Entrepreneurial Developer 09 Technology Disruptors Hold a Competitive 9 Labor Scarcity in Construction Costs Advantage 1 1 Housing Affordability: Local Governments 09 Global Uncertainties Weigh on the Mind Step Up 09 Ongoing Oil and Gas Woes 3 1 Gaining Entry beyond the Velvet Rope 29 Waiting for Deals 4 1 The Connectedness of Cities 92 Economic Outlook 5 1 Ready for Augmented Reality? 93 Property Type Outlook 7 1 Blockchain for 21st-Century Real Estate 69 Markets to Watch in 2017 8 1 Expected Best Bets for 2017 102 Expected Best Bets for 2017 02 Chapter 2 Capital Markets 104 Interviewees 1 2 The Debt Sector 72 The Equity Sector 33 Summary 43 Chapter 3 Markets to Watch 43 2017 Market Rankings 43 Market Summaries 1 7 Chapter 4 Property Type Outlook 2 7 Industrial 74 Apartments 67 Single-Family Homes 77 Hotels 79 Office 81 Retail 38 Niche Sectors 85 Summary Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2017 i Editorial Leadership Team Emerging Trends Chairs PwC Advisers and Contributing Researchers Mitchell M. -

Top 20 Music Tech Sites and Devices

Top 20 Online Music Websites for 2020 • 6:30pm – 7:30pm log in and participate live online audience Go To: https://kslib.zoom.us/j/561178181 The recording of this presentation will be online after the 18th @ https://kslib.info/1180/Digital-Literacy---Tech-Talks The previous presentations are also available online at that link Presenters: Nathan Carr, IT Supervisor, of the Newton Public Library and Randy Pauls Reasons to start your research at your local Library http://www.districtdispatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/triple_play_web.png 1. Protect your computer • A computer should always have the most recent updates installed for spam filters, anti-virus and anti-spyware software and a secure firewall. http://cdn.greenprophet.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/frying-pan-kolbotek-neoflam-560x475.jpg Types of Music Websites Music Blogs/Magazines/Forums: Talk about music. Formats, Artists, Styles, Instruments, Histories, events etc. Music Databases: Look up information about music related topics Pay Music Download Websites Free Music Download Websites P2P Music Download Websites Music on Demand Sites Online Music Broadcasts Making online music Live Music Event Promotion/Ticket Sales Music Blogs/Magazines/Forums: Talk about music. Formats, Artists, Styles, Instruments, Histories, events etc Blogs Magazines Forums Histories https://www.mi.edu/in-the-know/11-music-blogs-follow-2019/ http://www.tenthousandhoursmusic.com/blog/top-10-music-publications https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2019/09/6-great-online-music-forums-to-visit-when-youre-caught-in-a-jam.html -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS FEBRUARY 24, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] It’s Sam Hunt, Country Radio Seminar: An Older Folks >page 4 Medium Looks For Youthful Passion Positive Thoughts From CRS Mickey Guyton has yet to earn a hit record, but she still reaches the masses, remaining the most-listened-to media, >page 10 commandeered a standing ovation from broadcasters with a but the actual time spent listening is dwindling, and 18- to new song that was widely regarded as the stand-out musical 34-year-old country fans now devote more time to streaming moment of Country Radio Seminar. in an average week than they do to traditional broadcast radio. Was it a breakthrough moment? That can only be assessed by Additionally, programmers’ beliefs about the audience have not A Drink And A Nod programmers’ responses in the weeks and months ahead, but it kept up with changes in the playing field, or even their customers’ To Warner subtly pointed to radio’s current challenge: Do broadcasters play definition of radio. >page 11 it safe in a crowded media field? Or do they take a chance on a Younger listeners no longer view radio as a place that transmits talented artist who took her own risk on a song music from a tower, researcher Mark Ramsey that has the potential to change a listener’s life? said while unveiling a study of how consumers’ Guyton belted a gut-wrenching piano ballad, perceptions of broadcasting differ with PDs’ Big Machine’s New “What Are You Gonna Tell Her,” during the expectations. -

2014 Media Kit Covers.Indd

2014 MEDIA KIT PRINT | DIGITAL | EVENTS ABOUT THE VOICE OF MEDIA VOL. LV NO. 1 JANUARY 6-12, 2014 Merger MVPs LOOK WHO’S TALKING Thanks to the Internet of Things, we’ve fi nally arrived at the Jetsons age—and we’ll see it all at CES 00_0106_COVER_LO [P].indd 2 1/2/14 6:04 PM MUTUALLYU ASSURED THE VOICE OF MEDIA VOL. LIV NO. 40 NOVEMBER 11-17, 2013 5 353 s YYearsear Online streaming services are threatening to take down LASTNAME N: LINCOLN AGNEWLINCOLN N: SURVIVAL? T the bloated cable model. But success could lead them to IO FIRS kill their primary source of content. How will it all end? : By Sam Thielman ILLUSTRAT PHOTO 1 MONTH ##, #### | ADWEEK ADWEEK | MONTH ##, #### RonRon BergerBerger, formerlyformerly ofof EuroEuro RRSCG,SCG, aandnd hhisis ssonsons CCoryory BergerBerger ((l.)l.) ooff PPereiraereira & OO’Dell’Dell aandnd RRyanyan BBergererger ooff tthehe BBergererger SShop.hop. The Familyy In ccelebratioelebra n of our 35th anniversary, a pportfortfolioio of industry veterans and the sons and ddaughtersaugh to whom they’re passing the torch. THE VOICE OF MEDIA Updated: 6/16/14 PRINT Before you take the deep dive, here’s a peek at what’s ahead in the pages of the magazine First Mover Data Points Portrait The innovators, game changers, decision The latest in media, marketing and A close-up on the new generation of makers on their new jobs and how they got technology through the lens of data. advertising and media stars. from here to there. Trending Topics Accounts in Review Information Diet The hottest trends shaping the world of A weekly roundup of major accounts up Celebrities come clean on their media media, advertising and technology. -

Donna Cherry- Full-Length Biography November 3, 2013

-Donna Cherry- Full-Length Biography November 3, 2013 …the show's funniest moments belonged to Donna Cherry… doing what its title promised…a showstopper…. --New York Times …giving unpredictable snap to the evening… was the astounding Donna Cherry… --Boston Globe …bringing life and vigor to the stage…in the most striking performance, Donna Cherry stole the show…! --Los Angeles Times As an actor, comic, voice-over artist and singer extraordinaire, Ms. Cherry possesses the most rare of all acting combos: the qualities of a true character actress and the charisma of a leading lady. Donna grew up an “M.K.”, a missionary’s kid to Costa Rica and Colombia, where she was born the youngest of five kids. She entertained herself by listening to records for hours on end, imitating her favorite singers all day long. By the age of four, she performed her Thumbelina recording to perfection – including the scratches! After living in Latin America, her family settled in California. Her high school drama teacher inspired her to pursue a career as a performer, so she went on to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she began honing her acting skills. While completing her Bachelor of Music Degree (with a concentration in voice) from California State University, Northridge, she was approached while working as a singing waitress, by none other than Miss America herself, who saw her potential and encouraged her to enter the Miss America Pageant. After her very own personal extreme makeover, which included losing 25 pounds, Donna won Miss West Los Angeles and then the title of MISS CALIFORNIA! She bowled the judges over in the talent section with her series of impressions of show business legends…including MADONNA, BARBRA STREISAND, DIANA ROSS, ANITA BAKER, JOAN RIVERS, DOLLY PARTON and more.