"What's Going On": Motown and the Civil Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter Reso 1..4

*LRB09613384KXB28107r* HR0544 LRB096 13384 KXB 28107 r 1 HOUSE RESOLUTION 2 WHEREAS, The members of the Illinois House of 3 Representatives and State Representative Monique D. Davis are 4 saddened to learn of the death of Michael Jackson, who passed 5 away on June 25, 2009; and 6 WHEREAS, Michael Joseph Jackson was born on August 29, 1958 7 in Gary, Indiana to Joseph and Katherine Jackson; at the age of 8 4, he began singing with his brothers, Marlon, Jermaine, 9 Jackie, and Tito, as the Jackson 5; and 10 WHEREAS, By 1968, the Jacksons had cut singles for a local 11 Indiana label called Steeltown; at an engagement that year at 12 Harlem's famed Apollo Theater, singer Gladys Knight and pianist 13 Billy Taylor saw their act and recommended them to Motown 14 founder Berry Gordy; and 15 WHEREAS, Motown moved the Jacksons to California, and in 16 August 1968 they gave a breakthrough performance at a Beverly 17 Hills club called The Daisy; their first album, "Diana Ross 18 Presents the Jackson 5," was released in December 1969, and it 19 yielded the No. 1 hit "I Want You Back," with 11-year-old 20 Michael on the lead vocals; "ABC," "I’ll Be There," and other 21 hits followed, and the group soon had their own television 22 series, a Saturday morning cartoon, and an array of licensed -2-HR0544LRB096 13384 KXB 28107 r 1 merchandise aimed at youngsters; and 2 WHEREAS, By 1972, Michael Jackson had his first solo album, 3 "Got to Be There," which included the title hit as well as 4 "Rockin' Robin"; his first solo No. -

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (Guest Post)*

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (guest post)* The Temptations, c. 1964 The Temptations’ 1964 recording of “My Girl” came at a critical confluence for the group, the Motown label, and a culture roiling with the first waves of the British invasion of popular music. The five-man cell of disparate souls, later to be codified by black disc jockeys as the “tall, tan, talented, titillating, tempting Temptations,” had been knocking around Motown’s corridors and studio for three years, cutting six failed singles before finally scoring on the charts that year with Smokey Robinson’s cleverly spunky “The Way You Do the Things You Do” that winter. It rose to number 11 on the pop chart and to the top of the R&B chart, an important marker on the music landscape altered by the Beatles’ conquest of America that year. Having Smokey to guide them was incalculably advantageous. Berry Gordy, the former street hustler who had founded Motown as a conduit for Detroit’s inner-city voices in 1959, invested a lot of trust in the baby-faced Robinson, who as front man of the Miracles delivered the company’s seminal number one R&B hit and million-selling single, “Shop Around.” Four years later, in 1964, he wrote and produced Mary Wells’ “My Guy,” Motown’s second number one pop hit. Gordy conquered the black urban market but craved the broader white pop audience. The Temptations were riders on that train. Formed in 1959 by Otis Williams, a leather-jacketed street singer, their original lineup consisted of Williams, Elbridge “Al” Bryant, bass singer Melvin Franklin and tenors Eddie Kendricks and Paul Williams. -

"World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:23 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Résumé de l'article Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie This article traces the origins and uses of the musical classifications "world Volume 19, numéro 2, 1999 music" and "world beat." The term "world beat" was first used by the musician and DJ Dan Del Santo in 1983 for his syncretic hybrids of American R&B, URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014442ar Afrobeat, and Latin popular styles. In contrast, the term "world music" was DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar coined independently by at least three different groups: European jazz critics (ca. 1963), American ethnomusicologists (1965), and British record companies (1987). Applications range from the musical fusions between jazz and Aller au sommaire du numéro non-Western musics to a marketing category used to sell almost any music outside the Western mainstream. Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klump, B. (1999). Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1999 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

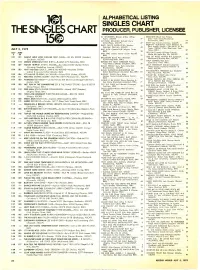

The Singles Chart

ALPHABETICAL LISTING 1 201 SINGLES CHART THE SINGLES CHART PRODUCER, PUBLISHER, LICENSEE AT SEVENTEEN Brooks Arthur (Mine/ MIDNIGHT BLUE Vini Poncia April, ASCAP) 77 (New York Times/Roumanian ATTITUDE DANCING Richard Perry Pickleworks, BMA) 14 15 (C'est/Maya, ASCAP) 47 MISTY Ray Stevens (Vernon, ASCAP) 23 BABY THAT'S BACKATCHA Smokey MORNIN' BEAUTIFUL Hank Medress & Dave Robinson (Bertram, ASCAP) 42 Appell (Apple Cider/Music of the Times, ASCAP; Little Max/New York JULY 5, 1975 BAD LUCK Gamble-Huff (Mighty Three, Times, BMI) 37 BMI) 39 JULY JUNE OLD DAYS James William Guercio BAD TIME Jimmy lenner (Cram Renraff, 5 28 (Make Me Smile/Big Elk, ASCAP) 52 BMI) 31 ONE OF THESE NIGHTS Bill Szymczyk 101 101 FUNNY HOW LOVE CAN BE FIRST CLASS-UK 5N 59033 (London) BALLROOM BLITZ Phil Wainman (Benchmark/Kicking Bear, ASCAP) 12 (Southern, ASCAP) (Chinnichap/RAK, BMI) 93 ONLY WOMEN Bob Ezrin BEFORE THE NEXT TEARDROP FALLS 102 110 DREAM MERCHANT NEW BIRTH-Buddah 470 (Saturday, BMI) (Ezra/Early Frost, BMI) 16 Huey Meaux (Shelby Singleton, BMI) 28 103 107 HONEY TRIPPIN' MYSTIC MOODS-Soundbird 5002 (Sutton Miller) ONLY YESTERDAY Richard Carpenter BLACK FRIDAY Gary Katz (American (Ginseng/Medallion Avenue, ASCAP) (Almo/Sweet Harmony/Hammer & Broadcasting, ASCAP) 43 Nails, ASCAP) 48 104 103 AIN'T NO USE COOK E. JARR & HIS KRUMS-Roulette 20426 BLACK SUPERMAN-MUHAMMAD ALI PHILADELPHIA FREEDOM Gus Dudgeon Robin Blanchflower Boy, BMI) 95 (Adam R. Levy & Father/Missile, BMI) (Drummer (Big Pig/Leeds, ASCAP) 54 105 104 IT'S ALL UP TO YOU JIM CAPALDI-Island D25 (Ackee, ASCAP) BURNIN' THING Gary Klein PLEASE MR. -

World Digipak Comp B.Indd

MOTOWN Around the World Visas Entries/Entrées Departures/Sorties 1 Visas Visas Entries/Entrées Departures/Sorties Entries/Entrées Departures/Sorties THE SOUND OF YOUNG AMERICA an outpouring. At Mrs. Edwards’ urging, Motown IL SUONO DELL’GIOVANE AMERICA complemented these bold moves with several recordings DER TON VON JUNGEM AMERIKA in German, Spanish, Italian, and, unknown to the public at LE BRUIT DE LA JEUNE AMÉRIQUE EL SONIDO DE AMÉRICA JOVEN the time, French. by Andrew Flory & Harry Weinger “We thought it would be hard to do, but learning the words and making the tracks work was enjoyable,” said Berry Gordy, Jr. founded Motown with the idea that his the Temptations’ Otis Williams, humming “Mein Girl” with a artists would cross borders, real and intangible. smile. “The people fl own in to teach us made it easy, and His bold idea would bloom in late 1964, when the we got it down just enough to be understood.” Supremes’ “Baby Love” hit No. 1 in the U.K., and “The Sound Of Young America,” as Motown later billed itself, spread around the world. Audiences who didn’t know English knew the words to Motown songs. The Motortown Revue went to Europe. Fan letters in every language showed up at West Grand Boulevard. Behind the infectious beat, inroads had been made overseas as early as spring 1963, when Mr. Gordy, along with Motown executives Esther Gordy Edwards and Barney Ales, made unprecedented sales visits to Italy, Germany, Belgium, Holland, France, Norway, Sweden and England. Two years later EMI U.K. created the Tamla Motown imprint, an international umbrella for the company’s multi-label output. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

The Impressions, Circa 1960: Clockwise from Top: Fred Cash, Richard Brooks> Curtis Mayfield, Arthur Brooks, and Sam (Pooden

The Impressions, circa 1960: Clockwise from top: Fred Cash, Richard Brooks> Curtis Mayfield, Arthur Brooks, and Sam (Pooden. Inset: Original lead singer Jerry Butler. PERFORMERS Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions BY J O E M cE W E N from the union of two friends, Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield of Chicago, Illinois. The two had sung together in church as adolescents, and had traveled with the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers and the Traveling Souls Spiritual Church. It was Butler who con vinced his friend Mayfield to leave his own struggling group, the Alfatones, and join him, Sam Gooden, and brothers Richard and Arthur Brooks— the remnants of another strug gling vocal group called the Roosters. According to legend, an impressive performance at Major Lance, Walter Jackson, and Jan Bradley; he also a Chicago fashion show brought the quintet to the at wrote music that seemed to speak for the entire civil tention of Falcon Records, and their debut single was rights movement. A succession of singles that began in recorded shortly thereafter. “For Your 1964 with “Keep On Pushing” and Precious Love” by “The Impressions SELECTED the moody masterpiece “People Get featuring Jerry Butler” (as the label DISCOGRAPHY Ready” stretched through such exu read) was dominated by Butler’s reso berant wellsprings of inspiration as nant baritone lead, while Mayfield’s For Your Precious Love.......................... Impressions “We’re A Winner” and Mayfield solo (July 1958, Falcon-Abner) fragile tenor wailed innocently in the recordings like “(Don’t Worry) If background. Several follow-ups He Will Break Your Heart......................Jerry Butler There’s A Hell Below We’re All Going (October 1960, Veejay) failed, Butler left to pursue a solo ca To Go” and “Move On Up,” placing reer, and the Impressions floundered. -

View Playbill

MARCH 1–4, 2018 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS BOOK BY BERRY GORDY MUSIC AND LYRICS FROM THE LEGENDARY MOTOWN CATALOG BASED UPON THE BOOK TO BE LOVED: MUSIC BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE MUSIC, THE MAGIC, THE MEMORIES SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING OF MOTOWN BY BERRY GORDY MOTOWN® IS USED UNDER LICENSE FROM UMG RECORDINGS, INC. STARRING KENNETH MOSLEY TRENYCE JUSTIN REYNOLDS MATT MANUEL NICK ABBOTT TRACY BYRD KAI CALHOUN ARIELLE CROSBY ALEX HAIRSTON DEVIN HOLLOWAY QUIANA HOLMES KAYLA JENERSON MATTHEW KEATON EJ KING BRETT MICHAEL LOCKLEY JASMINE MASLANOVA-BROWN ROB MCCAFFREY TREY MCCOY ALIA MUNSCH ERICK PATRICK ERIC PETERS CHASE PHILLIPS ISAAC SAUNDERS JR. ERAN SCOGGINS AYLA STACKHOUSE NATE SUMMERS CARTREZE TUCKER DRE’ WOODS NAZARRIA WORKMAN SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN DAVID KORINS EMILIO SOSA NATASHA KATZ PETER HYLENSKI DANIEL BRODIE HAIR AND WIG DESIGN COMPANY STAGE SUPERVISION GENERAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER CHARLES G. LAPOINTE SARAH DIANE WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS NANSCI NEIMAN-LEGETTE CASTING PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT TOUR BOOKING AGENCY TOUR MARKETING AND PRESS WOJCIK | SEAY CASTING PORT CITY TECHNICAL THE BOOKING GROUP ALLIED TOURING RHYS WILLIAMS MOLLIE MANN ORCHESTRATIONS MUSIC DIRECTOR/CONDUCTOR DANCE MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS ADDITIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ETHAN POPP & BRYAN CROOK MATTHEW CROFT ZANE MARK BRYAN CROOK SCRIPT CONSULTANTS CREATIVE CONSULTANT DAVID GOLDSMITH & DICK SCANLAN CHRISTIE BURTON MUSIC SUPERVISION AND ARRANGEMENTS BY ETHAN POPP CHOREOGRAPHY RE-CREATED BY BRIAN HARLAN BROOKS ORIGINAL CHOREOGRAPHY BY PATRICIA WILCOX & WARREN ADAMS STAGED BY SCHELE WILLIAMS DIRECTED BY CHARLES RANDOLPH-WRIGHT ORIGNALLY PRODUCED BY KEVIN MCCOLLUM DOUG MORRIS AND BERRY GORDY The Temptations in MOTOWN THE MUSICAL.