Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

Boom Boom Boom Boom by Steven Gowin

Boom Boom Boom Boom by Steven Gowin “You only just watch them damned cowboy shows and drink that cheap beer,” Lydia crabbed at Little Jessie. “Whyn't ya get out and do sumpin'? See a show that ain't Rawhide. Make a friend; don't be a worm no more.” Little Jessie'd spent 30 years taking orders in the Canal Zone with only brief visits home. He'd seen a fellow gamble away his life's savings, survived a near fatal explosion, and witnessed a man crushed and drowned in the Miraflores locks. “You like guitar?” Lydia badgered Jessie, when all he really wanted was a cold PBR, Gunsmoke, and some peace. “I said, guitar what you like?” Jessie nodded and said, “Sure enough, and squeeze box and saxophone, why?” “Why??? Why is cause I ain't standin' another night of you and them cowboys.” Lydia was one of those ladies who wears a big hat to church on Sunday, every Sunday. She said, “I know you know I'm right.” Jessie didn't care about right. He only cared about meanness and bossing and lack thereof. But Lydia was worse and worse. He couldn't do anything, say anything, without her telling him what was wrong with him. The next evening, holding the ticket Lydia'd bought him in hand, Jessie rode the 22 Fillmore across town to where the marquee flashed, John Lee's Boom BOOM R O O M ! ! ! The red and blue neon cheered Jessie, he admitted, and he liked the folks headed in wearing furs and finery and jewels. -

Rock and Roll Rockandrollismyaddiction.Wordpress.Com

The Band, Ten Years After , Keef Hartley Band , Doris Troy, John Lennon ,George Harrison, Leslie West, Grant Green, Eagles, Paul Pena, Bruce Springsteen, Peter Green, Rory Gallagher, Stephen Stills, KGB, Fenton Robinson, Jesse “Ed” Davis, Chicken Shack, Alan Haynes,Stone The Crows, Buffalo Springfield, Jimmy Johnson Band, The Outlaws, Jerry Lee Lewis, The Byrds , Willie Dixon, Free, Herbie Mann, Grateful Dead, Buddy Guy & Junior Wells, Colosseum, Bo Diddley, Taste Iron Butterfly, Buddy Miles, Nirvana, Grand Funk Railroad, Jimi Hendrix, The Allman Brothers, Delaney & Bonnie & Friends Rolling Stones , Pink Floyd, J.J. Cale, Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Humble Pie, Otis Spann Freddie King, Mike Fleetwood Mac, Aretha Bloomfield, Al Kooper Franklin , ZZ Top, Steve Stills, Johnny Cash The Charlie Daniels Band Wilson Pickett, Scorpions Black Sabbath, Iron Butterfly, Buddy Bachman-Turner Overdrive Miles, Nirvana, Son Seals, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton John Mayall, Neil Young Cream, Elliott Murphy, Años Creedence Clearwater Bob Dylan Thin Lizzy Albert King 2 Deep Purple B.B. King Años Blodwyn Pig The Faces De Rock And Roll rockandrollismyaddiction.wordpress.com 1 2012 - 2013 Cuando decidimos dedicar varios meses de nuestras vidas a escribir este segundo libro recopilatorio de más de 100 páginas, en realidad no pensamos que tendríamos que dar las gracias a tantas personas. En primer lugar, es de justicia que agradezcamos a toda la gente que sigue nuestro blog, la paciencia que han tenido con nosotros a lo largo de estos dos años. En segundo lugar, agradecer a todos los que en determinados momentos nos han criticado, ya que de ellas se aprende. Quizás, en ocasiones pecamos de pasión desmedida por un arte al que llaman rock and roll. -

The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA WHAT IS AN ORCHESTRA? Student Learning Lab for The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family ...................... 3 PART 2: Let’s Listen to Nagoya Marimbas ...................... 6 PART 3: Music Learning Lab ................................................ 8 2 PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family An orchestra consists of musicians organized by instrument “family” groups. The four instrument families are: strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Today we are going to explore the percussion family. Get your tapping fingers and toes ready! The percussion family includes all of the instruments that are “struck” in some way. We have no official records of when humans first used percussion instruments, but from ancient times, drums have been used for tribal dances and for communications of all kinds. Today, there are more instruments in the percussion family than in any other. They can be grouped into two types: 1. Percussion instruments that make just one pitch. These include: Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, wood block, gong, maracas and castanets Triangle Castanets Tambourine Snare Drum Wood Block Gong Maracas Bass Drum Cymbals 3 2. Percussion instruments that play different pitches, even a melody. These include: Kettle drums (also called timpani), the xylophone (and marimba), orchestra bells, the celesta and the piano Piano Celesta Orchestra Bells Xylophone Kettle Drum How percussion instruments work There are several ways to get a percussion instrument to make a sound. You can strike some percussion instruments with a stick or mallet (snare drum, bass drum, kettle drum, triangle, xylophone); or with your hand (tambourine). -

Love, Oh Love, Oh Careless Love

Love, Oh Love, Oh Careless Love Careless Love is perhaps the most enduring of traditional folk songs. Of obscure origins, the song’s message is that “careless love” could care less who it hurts in the process. Although the lyrics have changed from version to version, the words usually speak of the pain and heartbreak brought on by love that can take one totally by surprise. And then things go terribly wrong. In many instances, the song’s narrator threatens to kill his or her errant lover. “Love is messy like a po-boy – leaving you drippin’ in debris.” Now, this concept of love is not the sentiment of this author, but, for some, love does not always go right. Countless artists have recorded Careless Love. Rare photo of “Buddy” Bolden Lonnie Johnson New Orleans cornetist and early jazz icon Charles Joseph “Buddy” Bolden played this song and made it one of the best known pieces in his band’s repertory in the early 1900s, and it has remained both a jazz standard and blues standard. In fact, it’s a folk, blues, country and jazz song all rolled into one. Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues, cut an extraordinary recording of the song in 1925. Lonnie Johnson of New Orleans recorded it in 1928. It is Pete Seeger’s favorite folk song. Careless Love has been recorded by Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. Fats Domino recorded his version in 1951. Crescent City jazz clarinetist George Lewis (born Joseph Louis Francois Zenon, 1900 – 1968) played it, as did other New Orleans performers, such as Dr. -

4 Non Blondes What's up Abba Medley Mama

4 Non Blondes What's Up Abba Medley Mama Mia, Waterloo Abba Does Your Mother Know Adam Lambert Soaked Adam Lambert What Do You Want From Me Adele Million Years Ago Adele Someone Like You Adele Skyfall Adele Turning Tables Adele Love Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Aladdin A Whole New World Alan Silvestri Forrest Gump Alanis Morissette Ironic Alex Clare I won't Let You Down Alice Cooper Poison Amy MacDonald This Is The Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andreas Bourani Auf Uns Andreas Gabalier Amoi seng ma uns wieder AnnenMayKantenreit Barfuß am Klavier AnnenMayKantenreit Oft Gefragt Audrey Hepburn Moonriver Avicii Addicted To You Avicii The Nights Axwell Ingrosso More Than You Know Barry Manilow When Will I Hold You Again Bastille Pompeii Bastille Weight Of Living Pt2 BeeGees How Deep Is Your Love Beatles Lady Madonna Beatles Something Beatles Michelle Beatles Blackbird Beatles All My Loving Beatles Can't Buy Me Love Beatles Hey Jude Beatles Yesterday Beatles And I Love Her Beatles Help Beatles Let It Be Beatles You've Got To Hide Your Love Away Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Just The Two Of Us Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Billy Joel Honesty Billy Joel Souvenier Billy Joel She's Always A Woman Billy Joel She's Got a Way Billy Joel Captain Jack Billy Joel Vienna Billy Joel My Life Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel New York State Of Mind Birdy Skinny Love Birdy People Help The People Birdy Words as a Weapon Bob Marley Redemption Song Bob Dylan Knocking On Heaven's Door Bodo -

OUR Fnilfftl VOL. V, No. 5 SAVANNAH STATE COLLEGE PRESIDENT BENNER CRESWILL TURNER AUGUST, 1952 South Carolina State Prexy to De

37 HGEKS • ^ OUR fnilFftl 1QAH VOL. V, No. 5 SAVANNAH STATE COLLEGE AUGUST, 1952 PRESIDENT BENNER CRESWILL TURNER < Rev, Samuel Gandy Summer Study Calls Miss Camilla Williams, to Deliver 68th Faculty and Staff Soprano, To Be Baccalaureate Sermon at Savannah State Presented In Concert Rev. Samuel Lucius Gandy, Di- According to an announcement rector of Religious Activities at from Dr. W. K. Payne, president of Miss Camilla Williams, leading Virginia State College, Ettrick, Savannah State College, 16 faculty soprano of the City Virginia, New York will deliver the 68th Bac- and staff members are doing fur- Opera for five years, a concert calaureate sermon at Savannah ther study in their respective fields singer who has captivated two con- State College. The Baccalaureate this summer at some of the coun- tinents from Venezuela to northern services will be held in Meldrim try's leading universities. Alaska, a soloist with Auditorium, orchestra Sunday, August 10, at Those studying are: J. Randolph whose "beautiful singing" has 4:00 p. m. Fisher, associate professor of lan- been publicly praised by Stokowski, Reverend Gandy will be intro- guages and literature; Mrs. Elea- will be presented in Concert at Sa- duced by Dr. W. K. Payne, Presi- nor B. Williams, switchboard ope- vannah State College. dent of Savannah State. Invocation rator; and Joseph H. Wortham, as- Miss Williams and Benediction will appear in will be given by sistant professor of biology, all at Meldrim Auditorium, Friday, Au- Rev. A. J. Hargrett, Savannah Ohio State University. gust at State 8 8:30 p. m. in the second College Minister. -

The History of Cultural Production in the United States Tracks the Racial Divide That Inaugurated the Founding of the Republic

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND GENDER: OR LADY 1 SINGS THE BLUES BY K.J. GREENE The history of cultural production in the United States tracks the racial divide that inaugurated the founding of the Republic. The original U.S. Constitution excluded both black women and men from the blessings of liberty. Congress enacted formal laws mandating racial equality only scant decades ago, although it may seem long ago to today’s generation. Interestingly, the same Constitution that validated slavery and excluded women from voting also granted rights to authors and inventors in what is known as the Patent/Copyright clause of Article I, section 8. Those rights have become the cornerstone of economic value not only in the U.S but globally, and are inextricably tied to cultural production that influences all aspects of society. My scholarship seeks to show how both the structure of copyright law, and the phenomena of racial segregation and discrimination impacted the cultural production of African-Americans and how the racially neutral construct of IP has in fact historically adversely impacted African- American artists.2 It is only in recent years that scholarship exploring intellectual property has examined IP in the context of social and historical inequality. This piece will explore briefly how women artists and particularly black women have been impacted in the IP system, and to compare how both blacks and women have shared commonality of treatment with indigenous peoples and their creative works. The treatment of blacks, women and indigenous peoples in the IP system reflects an unfortunate narrative of exploitation, devaluation and the promotion of derogatory stereotypes that helped fuel oppression in the United States and in the case of indigenous peoples, aboard. -

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

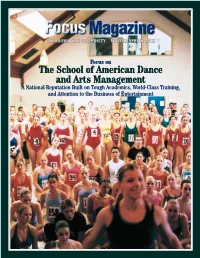

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35.