Communication and Legal Expression in Performance Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature

Bernadette Filotas PAGAN SURVIVALS, SUPERSTITIONS AND POPULAR CULTURES IN EARLY MEDIEVAL PASTORAL LITERATURE Is medieval pastoral literature an accurate reflection of actual beliefs and practices in the early medieval West or simply of literary conventions in- herited by clerical writers? How and to what extent did Christianity and traditional pre-Christian beliefs and practices come into conflict, influence each other, and merge in popular culture? This comprehensive study examines early medieval popular culture as it appears in ecclesiastical and secular law, sermons, penitentials and other pastoral works – a selective, skewed, but still illuminating record of the be- liefs and practices of ordinary Christians. Concentrating on the five cen- turies from c. 500 to c. 1000, Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature presents the evidence for folk religious beliefs and piety, attitudes to nature and death, festivals, magic, drinking and alimentary customs. As such it provides a precious glimpse of the mu- tual adaptation of Christianity and traditional cultures at an important period of cultural and religious transition. Studies and Texts 151 Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature by Bernadette Filotas Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Filotas, Bernadette, 1941- Pagan survivals, superstitions and popular cultures in early medieval pastoral literature / by Bernadette Filotas. -

Functional Responses and Intraspecific

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 115: 232–241, 2018 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.022 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Functional responses and intraspecifi c competition in the ladybird Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) provided with Melanaphis sacchari (Homoptera: Aphididae) as prey PENGXIANG WU 1, 2, J ING ZHANG 1, 2, M UHAMMAD HASEEB 3, S HUO YAN 4, LAMBERT KANGA3 and R UNZHI ZHANG 1, * 1 Department of Entomology, State Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Pest Insects and Rodents, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, #1-5 Beichen West Rd., Chaoyang, Beijing 100101, China; e-mails: [email protected] (Wu P.X.), [email protected] (Zhang J.), [email protected] (Zhang R.Z.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Center for Biological Control, Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL 32307-4100, USA; e-mails: [email protected] (Haseeb M.), [email protected] (Kanga L.) 4 National Agricultural Technology Extension and Service Center, Beijing 100125, China; e-mail: [email protected] (Yan S.) Key words. Coleoptera, Coccinellidae, Harmonia axyridis, Hemiptera, Aphididae, Melanaphis sacchari, functional response, intraspecifi c competition Abstract. Functional responses at each developmental stage of predators and intraspecifi c competition associated with direct interactions among them provide insights into developing biological control strategies for pests. The functional responses of Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) at each developmental stage of Melanaphis sacchari (Zehntner) and intraspecifi c competition among predators were evaluated under laboratory conditions. The results showed that all stages of H. axyridis displayed a type II func- tional response to M. -

Exploring Historical Anthropology Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J

Exploring Historical Anthropology Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J. Gurevich Leonore Scholze-Irrlit z Scholze-Irrlitz, Leonore 1994 : Exploring Historical Anthropology. Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J. Gurevich . - Ethnologia Europaea 24: 119-132. The different styles of research of two historians - Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J . Gurevich - are analysed and compared. Both understand anthropology as th e basis of a new all-encompassing attempt at synthesising historical studies, and produce ind ependent results by taking into consideration lit erary-hermeneut ical, ethnological and structuralistic methods, thus forming two different co existing "styles of relationship" of medieval mentality. Le Goff and Gurevich contribute to historical anthropology and to a publicly effective renewal of the science of history through explanatory, deterministic and contemporary exam ination. An interview with A. J. Gurevich on the relationship between social history and the history of mentality is published as an append ix. Dr. phil. Leonore Scholze-Irrlitz, Eichbergstr. 23, D-12589 Berlin-Wilhelmsha gen. This paper deals with the styles of research and space (Le Goff 1970: 215 and 1977: 25, Le and the methods of Jacques Le Goff and Aaron Goff & Chartier 1990: 13). Significant for the J. Gurevich - two historians from very differ "Annales" school and also for Le Goff are fur ent scientific traditions. The contribution both ther the comparative methods of historical in of these medieval specialists have made to his terpretation and the concept of "histoire to torical anthropology reveals new dimensions tale" (Le Goff 1983 : XI, Honegger 1977: 13-14, in the science of history. Burke 1991: 29). The "Annales" went through three stages of development, the last of which is characterized by J. -

C:\Users\John Munro\Documents\Wpdocs

Prof. John H. Munro [email protected] Department of Economics [email protected] University of Toronto http://www.economics.utoronto.ca/munro5/ Revised: 22 August 2013 ECO 301Y1 The Economic History of Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Topic No. 5 [7]: The Church, the Usury Doctrine, and Late-Medieval Banking: Institutional Impediments to Medieval Economic Growth? A. The Church and the Usury Doctrine: * 1. Lawrin Armstrong, ‘Usury’, in Joel Mokyr, et al, eds., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, 5 vols. (New York, 2003), vol. 5, pp. 183-85. * 2. James A. Brundage, ‘Usury’, in Joseph R. Strayer, et al, eds., Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 13 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons-MacMillan, 1982-89), Vol. XII (1989), pp. 335-39. * 3. Richard Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (London, 1926), chapter 1, ‘The Medieval Background’, pp. 11-60. * 4. John T. Noonan, The Scholastic Analysis of Usury (Cambridge, Mass. 1957), Part One: chapters I- II, pp. 11-37, especially III, ‘A Natural Law Case Against Usury’, pp. 38-81; V, pp. 100-33. * 5. Mark Koyama, ‘Evading the “Taint of Usury”: The Usury Prohibition as a Barrier to Entry’, Explorations in Economic History, 47:4 (October 2010), 420-42. Very mathematical; but the econometrics may appeal to economics specialists. * 6. John Munro, ‘The Medieval Origins of the Modern Financial Revolution: Usury, Rentes, and Negotiablity’, The International History Review, 25:3 (September 2003), 505-62. * 7. Jared Rubin, ‘Bills of Exchange, Interest Bans, and Impersonal Exchange in Islam and Christianity’, Explorations in Economic History, 47:2 (April 2010), 211-27. -

Samuel Oldknow Papers, 1782-1924"

Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies Volume 8 Article 10 2021 Greening the Archive: The Social Climate of Cotton Manufacturing in the "Samuel Oldknow Papers, 1782-1924" Bernadette Myers Columbia University, [email protected] Melina Moe Columbia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas Part of the Agriculture Commons, Archival Science Commons, Economic History Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Myers, Bernadette and Moe, Melina (2021) "Greening the Archive: The Social Climate of Cotton Manufacturing in the "Samuel Oldknow Papers, 1782-1924"," Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 8 , Article 10. Available at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol8/iss1/10 This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies by an authorized editor of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myers and Moe: Greening the Archive GREENING THE ARCHIVE: THE SOCIAL CLIMATE OF COTTON MANUFACTURING IN THE SAMUEL OLDKNOW PAPERS, 1782–1924 On New Year's Day 1921, historians George Unwin and Arthur Hulme made their way to a ruined cotton mill located on the Goyt River in Mellor, England. Most of the mill had been destroyed by a fire in 1892, but when the historians learned that a local boy scout had been distributing eighteenth-century weavers’ pay tickets to passersby, they decided to investigate. On the upper level of the remaining structure, beneath several inches of dust and debris, they found hundreds of letters, papers, account books, and other documents scattered across the floor. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Nous avons de´place´ les notions et confondu leurs veˆtements avec leurs noms aveugles sont les mots qui ne savent retrouver que leur place de`s leur naissance leur rang grammatical dans l’universelle se´curite´ bien maigre est le feu que nous cruˆmes voir couver en eux dans nos poumons et terne est la lueur pre´destine´e de ce qu’ils disent —Tristan Tzara, L’homme approximatif THIS BOOK is an essay. Its surface object is political ritual in the early Middle Ages. By necessity, this object must be vague, because historians have, col- lectively at least, piled a vast array of motley practices into the category. In the process, no doubt, splendid studies have vastly enlarged the historical discipline’s map of early medieval political culture.1 We are indebted for many stimulating insights to the crossbreeding of history and anthropol- ogy—an encounter that began before World War II and picked up speed in the 1970s. From late antiquity to the early modern era, from Peter Brown to Richard Trexler, it revolutionized our ways of looking at the past. In this meeting, ritual loomed large.2 Yet from the start, it should be said that the present essay ends up cau- tioning against the use of the concept of ritual for the historiography of the Middle Ages. It joins those voices that have underscored how social- scientific models should be employed with extreme caution, without eclec- ticism, and with full and constant awareness of their intellectual genealo- gies.3 In the pages that follow, then, the use of the term “ritual” is provi- sional and heuristic (the ultimate aim being to suggest other modes of 1 See, e.g., Gerd Althoff, Spielregeln der Politik im Mittelalter. -

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie Synthetic Worlds Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2005 Copyright © Esther Leslie 2005 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Colour printed by Creative Print and Design Group, Harmondsworth, Middlesex Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Leslie, Esther, 1964– Synthetic worlds: nature, art and the chemical industry 1.Art and science 2.Chemical industry - Social aspects 3.Nature (Aesthetics) I. Title 7-1'.05 isbn 1 86189 248 9 Contents introduction: Glints, Facets and Essence 7 one Substance and Philosophy, Coal and Poetry 25 two Eyelike Blots and Synthetic Colour 48 three Shimmer and Shine, Waste and Effort in the Exchange Economy 79 four Twinkle and Extra-terrestriality: A Utopian Interlude 95 five Class Struggle in Colour 118 six Nazi Rainbows 167 seven Abstraction and Extraction in the Third Reich 193 eight After Germany: Pollutants, Aura and Colours That Glow 218 conclusion: Nature’s Beautiful Corpse 248 References 254 Select Bibliography 270 Acknowledgements 274 Index 275 introduction Glints, Facets and Essence opposites and origins In Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow a character remarks on an exploding missile whose approaching noise is heard only afterwards. The horror that the rocket induces is not just terror at its destructive power, but is a result of its reversal of the natural order of things. -

From Yoder to Yoda: Traditional, Modern and Postmodern Models of Religion in U.S

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1999 From Yoder to Yoda: Traditional, Modern and Postmodern Models of Religion in U.S. Constitutional Law Rebecca Redwood French University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Rebecca R. French, From Yoder to Yoda: Traditional, Modern and Postmodern Models of Religion in U.S. Constitutional Law, 41 Ariz. L. Rev. 49 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/99 Copyright 1999 by Arizona Board of Regents and Rebecca R. French. Reprinted with permission of the authors and publisher. This article originally appeared in Arizona Law Review, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 49–92. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM YODER TO YODA: MODELS OF TRADITIONAL, MODERN, AND POSTMODERN RELIGION IN U.S. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW Rebecca Redwood French* I. INTRODUCTION The Supreme Court and its commentators have been struggling for over a century to find an adequate definition or characterization of the term "religion" in the First Amendment.! It has turned out to be a particularly tricky endeavor, one that has stumped both the Court and its commentators. -

Supplier Name

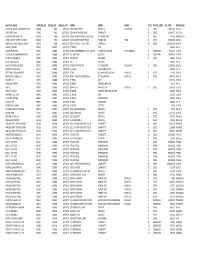

SUPPLIER_NAME SUPPLIER_NO CHEQUE_NO CHEQUE_DATE ADDR1 ADDR2 ADDR3 STATE POSTAL_CODE INV_PAID INVOICE_NO OFFICE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SRF 04368 9683 6/3/2019 1201 MAIN STREET SUITE 910 COLUMBIA SC 29201 13,825.00 5-31-19 SOUTHEAST JACK C4690 9684 6/17/2019 7000 W WT HARRIS BLVD CHARLOTTE NC 28269 14,064.73 L6-17-19 GLOBAL AEROSPACE, INC. 09568 9686 6/17/2019 10895 GRANDVIEW DR, SUITE 150 OVERLAND PARK KS 66210 975.00 I00061547/01 YORK COUNTY CLERK OF COURT 00538 9687 6/26/2019 YORK COUNTY COURTHOUSE P O BOX 649 YORK SC 29745 35,000.00 6-26-19 JAMES, MCELROY & DIEHL TRUST 09567 9688 6/26/2019 525 N TRYON ST., SUITE 700 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 125,000.00 6-26-19 GIBSON, STEVEN 00957 230879 6/7/2019 EE #2679 OMB 209.96 6-2-19 UNUM PROVIDENT 01935 230880 6/7/2019 ATTN: VWB PREMIUM CLTN. & ACCT 1 FOUNTAIN SQUARE CHATTANOOGA TN 374021362 3,742.76 4-25-19 COMPORIUM COMMUNICATIONS 01951 230881 6/7/2019 P.O. BOX 1042 ROCK HILL SC 297317042 14,949.05 5-29-19 SC DEPT OF REVENUE 02000 230882 6/7/2019 TAX RETURN COLUMBIA SC 29214 486.00 5-31-19 SCOTT, MICHAEL W. 03826 230883 6/7/2019 CRH FIRE DEPT 200.00 6-5-19 BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD 04295 230884 6/7/2019 OF SOUTH CAROLINA P.O. BOX 6000 COLUMBIA SC 29260 11,959.40 5-21-19 BROWN, PAULA KNOX 06154 230885 6/7/2019 EE # 5036 SOLICITOR'S OFFICE 100.00 6-5-19 PRT TENNIS TOURNAMENT 06465 230886 6/7/2019 ATTN: 897 MAPLEWOOD LANE ROCK HILL SC 29730 112.00 5-29-19 NEXT LEVEL TENNIS, LLC 06525 230887 6/7/2019 ATTN: TEODORA DONCHEVA 872 DILLARD RD ROCK HILL SC 29730 7,897.60 N6-3-19 BROWN, LISA 07325 230888 6/7/2019 EE #5855 OMB 1,673.20 5-29-19 WINKLER, JEREMY 07922 230889 6/7/2019 EE #4207 GENERAL SERVICES 81.20 6-3-19 H.O.P.E. -

Peter Brown T He Rise of W

Brown Brown “This book remains a classic, easily the most fascinating introduction to the fi eld for anyone new to it, and also capable of forcing experts into taking on new ideas; a summation of Peter Brown’s mould-breaking work.” Chris Wickham, University of Oxford TENTH ANNIVERSARY REVISED EDITION TENTH ANNIVERSARY The Rise of Christendom Western TENTH ANNIVERSARY REVISED EDITION TENTH ANNIVERSARY The Rise of Christendoms Western “Interpretations of late antiquity and of western Christendom have changed dramatically in the last decade. This anniversary edition explains the changes with Peter Brown’s characteristic brilliance and range of learning.” Gillian Clark, University of Bristol The publication of this revised edition of a masterwork by Princeton University’s celebrated scholar of late antiquity marks the book’s tenth anniversary. A central volume in the Wiley- Blackwell series The Making of Europe, the book has undergone a thorough redesign and includes a new preface covering academic developments in the last ten years, revised common opinions, a fully updated bibliography, and additional color images. As a superbly realized account of the compelling history of Christianity’s evolution in its tumultuous fi rst millennium, it is the essential general survey of the subject. Brown charts the rise to prominence of a religion that began as an obscure sect in Roman Judaea and developed into Europe’s dominant religious – and political – institution. Christianity played a pivotal role in the making of Europe, as well as the delineation of its boundaries: the political gulf between Europe and its eastern neighbors TheThe RiseRise was also a religious divide. -

Accepting the Invisible Hand: Market-Based Approaches to Social-Economic Problems Edited by Mark D

ACCEPTING THE INVISIBLE HAND Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to ETH Zuerich - PalgraveConnect - 2011-04-15 - PalgraveConnect - licensed to ETH Zuerich www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230114319 - Accepting the Invisible Hand, Edited by Mark D. White 9780230102491_01_prexvi.indd i 9/6/2010 1:17:11 PM PERSPECTIVES FROM SOCIAL ECONOMICS Series Editor: Mark D. White, Professor in the Department of Political Science, Econom- ics, and Philosophy at the College of Staten Island/CUNY. The Perspectives from Social Economics series incorporates an explicit ethical component into contemporary economic discussion of important policy and social issues, drawing on the approaches used by social economists around the world. It also allows social economists to develop their own frameworks and paradigms by exploring the philosophy and methodology of social eco- nomics in relation to orthodox and other heterodox approaches to econom- ics. By furthering these goals, this series will expose a wider readership to the scholarship produced by social economists, and thereby promote the more inclusive viewpoints, especially as they concern ethical analyses of economic issues and methods. Accepting the Invisible Hand: Market-Based Approaches to Social-Economic Problems Edited by Mark D. White Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to ETH Zuerich - PalgraveConnect - 2011-04-15 - PalgraveConnect - licensed to ETH Zuerich www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230114319 - Accepting the Invisible Hand, Edited by Mark D. White 9780230102491_01_prexvi.indd ii 9/6/2010 1:17:11 PM Accepting the Invisible Hand Market-Based Approaches to Social-Economic Problems Edited by Mark D. White Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to ETH Zuerich - PalgraveConnect - 2011-04-15 - PalgraveConnect - licensed to ETH Zuerich www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230114319 - Accepting the Invisible Hand, Edited by Mark D.