The Annals of UVAN, Volume X, 1962-1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

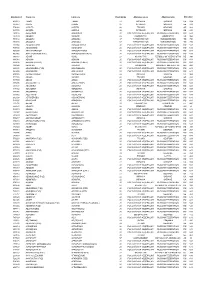

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2021

Part 3 of THE YEAR IN REVIEW pages 7-13 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXIX No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 $2.00 Ukraine celebrates Unity Day Ukraine’s SBU suspects former agency colonel of plotting to murder one of its generals by Mark Raczkiewycz KYIV – On January 27, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) said it had secured an arrest warrant for Dmytro Neskoromnyi, a former first deputy head of the agency, on suspicion of conspiring to murder a serving SBU general. Mr. Neskoromnyi, a former SBU colonel, allegedly plotted the assassination with currently serving Col. Yuriy Rasiuk of the SBU’s Alpha anti-terrorist unit. The alleged target was 38-year-old Brig. Gen. Andriy Naumov. Mr. Naumov heads the agency’s internal security department, which is responsible for preventing corruption among the SBU’s ranks. RFE/RL In a news release, the SBU provided video RFE/RL A human chain on January 22 links people along the Paton Bridge in Kyiv over the and audio recordings, as well as pictures, as Security Service of Ukraine Brig. Gen. Dnipro River that bisects the Ukrainian capital, symbolizing both sides uniting when evidence of the alleged plot. The former col- Andriy Naumov the Ukrainian National Republic was formed in 1919. onel was allegedly in the process of paying “If there is a crime, we must act on it. $50,000 for carrying out the murder plot. by Roman Tymotsko (UPR), Mykhailo Hrushevskyy. And, in this case, the SBU worked to pre- Mr. -

Ukrainian Revolution”

© 2018 Author(s). Open Access. This article is “Studi Slavistici”, xv, 2018, 2: 141-154 distributed under the terms of the cc by-nc-nd 4.0 doi: 10.13128/Studi_Slavis-22777 Submitted on 2018, February 25th issn 1824-761x (print) Accepted on 2018, October 19th issn 1824-7601 (online) Ulrich Schmid Volodymyr Vynnyčenko as Diarist, Historian and Writer. Literary narratives of the “Ukrainian Revolution” Volodymyr Vynnyčenko was an acclaimed writer at the time of his inauguration as head of the Ukrainian state in 1918. He firmly believed in the possibility of combining po- litical independence with a just social order. When the Bolsheviks established the Soviet Ukrainian Republic in 1919, he left the country. For a short time, he offered his service to the new government and hoped the state would develop into a national communist system. Among all available options, the Bolsheviks seemed to provide the best perspectives for a socialist Ukrainian state. For quite a long time, Vynnyčenko was convinced of the following syllogism: The Ukrainian nation is comprised of proletarians. The Bolsheviks are the natural advocates of the proletarian cause. Hence they must also support the Ukrainian national cause (Gilley 2006: 513, 518). However, the situation turned out to be more complicated. Gripped by disappointment, Vynnyčenko eventually declared his dissolution with politics, and announced his intention to live on as a writer. However, in 1935 he stressed his inability to separate political views from his literary and artistic activities (Stelmashenko 1989: 260). Undoubtedly, the main event in Vynnyčenko’s adventurous life was what he called the “Ukrainian revolution”. -

A Guide to the Archival and Manuscript Collection of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., New York City

Research Report No. 30 A GUIDE TO THE ARCHIVAL AND MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., NEW YORK CITY A Detailed Inventory Yury Boshyk Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Edmonton 1988 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Occasional Research Reports Publication of this work is made possible in part by a grant from the Stephania Bukachevska-Pastushenko Archival Endowment Fund. The Institute publishes research reports periodically. Copies may be ordered from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 352 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2E8. The name of the publication series and the substantive material in each issue (unless otherwise noted) are copyrighted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. PRINTED IN CANADA Occasional Research Reports A GUDE TO THE ARCHIVAL AND MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., NEW YORK CITY A Detailed Inventory Yury Boshyk Project Supervisor Research Report No. 30 — 1988 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta Dr . Yury Boshyk Project Supervisor for The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Research Assistants Marta Dyczok Roman Waschuk Andrij Wynnyckyj Technical Assistants Anna Luczka Oksana Smerechuk Lubomyr Szuch In Cooperation with the Staff of The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S. Dr. William Omelchenko Secretary General and Director of the Museum-Archives Halyna Efremov Dima Komilewska Uliana Liubovych Oksana Radysh Introduction The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States, New York City, houses the most comprehensive and important archival and manuscript collection on Ukrainians outside Ukraine. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The Vasil Krychevsky Poltava Local Lore Museum: from Foundation to the Present

Scientific Development of New Eastern Europe THE VASIL KRYCHEVSKY POLTAVA LOCAL LORE MUSEUM: FROM FOUNDATION TO THE PRESENT Zaiets Taras1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30525/978-9934-571-89-3_63 Poltava region has always attracted the interest of scientists, as determined by the dynamics of social and cultural and artistic life. The region has a special approach in historical musicology, folklore and ethnography. An in-depth study of the history of the formation of museums is an actual topic in the modern conditions of the revival of spirituality and culture of the Ukrainian people. Nevertheless, in spite of this, the topics of the Poltava Museology are covered only in a fragmentary way in the studies of N. Besedina, A. Vasylenko, V. Vrublevska, G. Mezentseva, M. Ozhitska, I. Yavtushenko and some other scholars. The rich history of the Poltava region is preserved in museums, the oldest of which is the Poltava Local Lore Museum – a significant scientific and cultural center, created in 1891 at the Poltava provincial zemstvo board in three small rooms of the wing. The first exhibits of the institution was a collection of soils and herbarium collected by the expedition of the famous scientist, professor V. V. Dokuchaev – 4,000 soils, 500 specimens of rocks, 862 herbarium sheets [5]. In 1908, the architect V. Krychevsky and the painters S. Vasylkivsky (who performed the decorative painting of the museum) and M. Samokysh (created three huge canvases in the session hall of the zemstvo) built a genuine architectural masterpiece, which is still considered the most original building in the city. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2001, No.37

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Verkhovna Rada finally passes election law — page 3. •A journal from SUM’s World Zlet in Ukraine — pages 10-11. • Soyuzivka’s end-of-summer ritual — centerfold. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX HE No.KRAINIAN 37 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2001 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine UKRAINE REACTS TO TERRORIST ATTACKS ON U.S. EU Tand UkraineU W by Roman Woronowycz President Leonid Kuchma, who had and condemned the attacks, according to Kyiv Press Bureau just concluded the Ukraine-European Interfax-Ukraine. meet in Yalta Union summit in Yalta with European “We mourn those who died in this act KYIV – Ukraine led the international Commission President Romano Prodi and response to the unprecedented terrorist of terrorism,” said Mr. Prodi. European Union Secretary of Foreign and Immediately upon his return from for third summit attacks on Washington and New York on Security Policy Javier Solana on by Roman Woronowycz September 11 when its Permanent Yalta, President Kuchma first called a Kyiv Press Bureau September 11, issued a statement express- special meeting of the National Security Mission to the United Nations called a ing shock and offering condolences. and Defense Council for the next day and KYIV – Leaders of the European special meeting of the U.N. Security Messrs. Prodi and Solana, who were at Union and Ukraine met in Yalta, Crimea, Council to coordinate global reaction. Symferopol Airport in Crimea on their then went on national television to call For security reasons, the meeting was on September 10-11 for their third annu- way back to Brussels, expressed shock (Continued on page 23) al summit – the first in Ukraine – which held outside the confines of the United had been advertised as a turning point Nations at the mission headquarters of during which relations would move from the Ukrainian delegation in New York. -

Volodymyr Vynnychenko and the Early Ukrainian Decadent Film (1917–1918)

УДК 008:791.43.01 O. Kirillova volodymyr vynnychenKo and the early uKrainian decadent film (1917–1918) The article is focused on the phenomenon of the early Ukrainian decadent cinema, in particular, in rela- tion to filmings of Volodymyr Vynnychenko’s dramaturgy. One of the brightest examples of ‘film decadence’ in Vynnychenko’s oevre is “The Lie” directed by Vyacheslav Vyskovs’ky in 1918, discovered recently in the film archives. This film displays the principles of ‘ethical symbolism’, ‘dark’ expressionist aesthetics and remains the unique masterpiece of specifically Ukranian film decadence. Keywords: decadent film, fin de sciècle, cultural diffusion, cultural split, ethical symbolism, filming, editing. The early Ukranian decadent film as an integral screening, «The Devil’s Staircase», filmed by a Rus part of the trend of decadence in the world cinema sian producer Georgiy Azagarov in 1917 (released can be regarded as a specific problem for research in February 1918) put the central conflict in the area ers because of its diffusion within the cinematogra of circus actors. This film had been considered des phy of Russian Empire. Ukrainian subjects in the perately lost. The second “Black Panther” was taken cinema of 1910s, on the one hand, had traditionally into production by Sygyzmund Kryzhaniv’sky on been related to «ethnographical topics» (to begin “Ukrainfil’m” – in 1918. Unfortunately, the produc with the one of the earliest Russian silents «Taras tion had not been finished due to the regular change Bul’ba», 1909, after Mykola Hohol’), but, on the of government in Ukraine. Finally, the third one, other hand, had been represented partly in Russian “Die Schwarze Pantherin” filmed in Germany by film, though totally diffused in its cultural contexts. -

Ukrainian Literature in English: Articles in Journals and Collections, 1840-1965

Research Report No. 51 UKRAINIAN LITERATURE IN ENGLISH: ARTICLES IN JOURNALS AND COLLECTIONS, 1840-1965 An annotated bibliography MARTA TARNAWSKY Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press University of Alberta Edmonton 1992 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press Occasional Research Reports The Institute publishes research reports periodically. Copies may be ordered from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 352 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G2E8. The name of the publication series and the substantive material in each issue (unless otherwise noted) are copyrighted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press. This publication was funded by a grant from the Stephania Bukachevska-Pastushenko Archival Endowment Fund. PRINTED IN CANADA 1 Occasional Research Reports UKRAINIAN LITERATURE IN ENGLISH: ARTICLES IN JOURNALS AND COLLECTIONS, 1840-1965 An annotated bibliography MARTA TARNAWSKY Research Report No. 5 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press University of Alberta Edmonton 1992 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Journals and Collections Included in this Bibliography ix Bibliography 1 General Index 144 Chronological Index 175 INTRODUCTION The general plan Ukrainian Literature in English: Articles in Journals and Collections. 1840-1965 is part of a larger bibliographical project which attempts, for the first time, a comprehensive coverage of translations from and materials about Ukrainian literature published in the English language from the earliest known publications to the present. After it is completed this bibliographical project will include: 1/books and pamphlets, both translations and literary studies; 2/articles and notes published in monthly and quarterly journals, yearbooks, encyclopedias, symposia and other collections; 3/translations of poetry, prose and drama published in monthly and quarterly journals, yearbooks, anthologies etc.; and 4/ book reviews published in journals and collections. -

TULA М4 Rail М2 М2

CATALOGUE OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS EXPORTED BY THE TULA REGION 1 CATALOGUE CONTENTS INFORMATION 3 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 6 METALLURGICAL INDUSTRY 16 CHEMICAL INDUSTRY 25 LIGHT INDUSTRY 36 FOOD INDUSTRY 48 CONTACT INFORMATION 62 2 CATALOGUE CONTENTS “THE FOREIGN TRADE TURNOVER STRUCTURE NOW MEETS ALL THE CRITERIA FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND IS EXPORT-ORIENTED. WE NEED TO INCREASE THE VOLUME OF EXPORTS AND FIND NEW SALES MARKETS.” Governor of the Tula Region Alexei Dyumin 3 TULA REGION TRADE WITH MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS: 126 USA, CHINA, COUNTRIES BELARUS, ALGERIA, TURKEY, UAE, GERMANY 36,2% Chemical industry products and rubber 28,1% Other goods 6,8% Mechanical engineering products 5% Foods and raw materials Population Total area Tula Novomoskovsk 23,9% Metals and metal 1 466 127 25 700 550,8 125,2 products people sq. km thousand people thousand people EXPORT STRUCTURE EXPORT 4 TULA REGION MOSCOW М2 MOSCOW REGION TWO FEDERAL HIGHWAYS • M2 ‘Crimea’ М4 Zaokskiy Rail • M4 ‘Don’ KALUGA REGION Aleksin RAILWAY ROUTES Yasnogorsk • MOSCOW–KHARKOV–SIMFEROPOL, Venoyv • MOSCOW–DONBAS; TULA TRANSPORT ROUTES Dubna Suvorov Novomoskovsk RYAZAN REGION • Tula – M4 ‘Don’ Transcaucasia, Western Asia (part of the Chekalin Shchyokino Uzlovaya Kimovsk European route E 115) Odoyev Kireyevsk • Tula – M2 ‘Crimea’ Europe (part of the European route E105) Belyov Arsenyevo Bogoroditsk Plavsk Tyoploye Volovo AIR TRAFFIC: • Sheremetyevo (210 km) – more than 230 domestic and М2 Chern Kurkino international destinations • Domodedovo (170 km) – 194 destinations Arkhangelskoye LIPETSK • Vnukovo (180 km) – more than 200,000 domestic and REGION international destinations ORYOL REGION Yefremov • Kaluga Airport (110 km) – 9 domestic destinations М4 5 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING THE TULAMASHZAVOD PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION The TULAMASHZAVOD Production Association is a major holding that includes the parent TULAMASHZAVOD Joint-Stock Company and twenty subsidiaries that focus equally on both the manufacturing of products for the defence industry and civilian products.