Commission on Highland Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

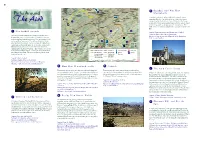

C:\MYDOCU~1\ACCESS~2\Aird\New Aird Inside.Pmd

Wester To Inverness Lovat Kirkhill 6 Kirkhill and Wardlaw Wardlaw 6 Paths Around Beauly Mausoleum Ferry Brae Bogroy A roadside path to the village of Kirkhill and to the burial To Lentran Beauly ground used by the Clan Fraser of Lovat. Robert the Bruce’s The Aird 7 Inchmore chamberlain was Sir Alexander Fraser. His brother, Sir Simon A862 acquired the Bisset Lands around Beauly when he won the hand ! of its heiress, and these lands became the family home. The walk can be extended by following the cycle route as far as Ferry Brae. 1 Newtonhill circuits 1 2 ! Cabrich Approx 5 kms round trip to the Mausoleum (3.1 miles) Moniack Newtonhill Castle Parking at Bogroy Inn or at the Mausoleum This varied circular walk on quiet country roads provides a A833 A Bus service from Inverness and Dingwall to the Bogroy Inn flavour of what the Aird has to offer; agricultural landscape, 5 To Easy - sensible footwear natural woodland, plantations of Scots Pine and mature beech To Kiltarlity Kirkton and magnificent panoramas. The route provides links to the 4 3 Muir other paths in the network. It offers views to the Fannich and Belladrum Mám Mòr To the Affric ranges to the north and west, views to the east down the 8 Reelig Great Moray Firth and some of the best views to Ben Wyvis. The THE AIRD A Glen Glen Way climb from Reelig Glen is worth the effort with the descent via Newtonhill and Drumchardine, a former weaving community A Phoineas Newtonhill Circuit The Cabrich Tourist Information A Access point providing an easy finish. -

Executive Summary NHS Highland Pharmaceutical Care Services Plan 2013-2014

Executive Summary NHS Highland Pharmaceutical Care Services Plan 2013-2014 The NHS (Pharmaceutical Services) (Scotland) Amendment regulations 2011 require NHS Boards to publish pharmaceutical care plans and update them annually. The purpose of this Pharmaceutical Care Services Plan (PCS Plan) is to provide information on the pharmaceutical care services currently available within NHS Highland. This will help us find any potential gaps in service provision and identify where there may be a need for a pharmaceutical service. A secondary function of the plan is to inform and engage members of the public, health professions and planners in the planning of pharmaceutical services. The Pharmacy Practices Committee will use the Board’s PCS Plan when considering applications to join the Pharmaceutical List. The pharmaceutical needs of the local community will be the main determinant of whether an additional community pharmacy or relocation will be approved by them. PCS planning provides a mechanism to determine the number of premises providing NHS pharmaceutical services, by responding as closely as possible to the need of the local population for those services. Boards will develop a pharmaceutical care needs assessment process to assess what pharmaceutical care services are needed by the population; what services are currently provided; define and quantify the gap in service provision and; describe plans to close the gap. The underpinning approach will be a scientific study of population and health. The views and experience of those involved locally in planning and providing pharmaceutical services in particular, and health services in general, are also key to the planning process. This second PCS Plan is mostly narrative in nature with limited gap analysis. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

BCS Paper 2016/15 2018 Review of UK Parliament Constituencies Constituency Considerations for Argyll and Bute, Highland and Mora

Boundary Commission for Scotland BCS Paper 2016/15 2018 Review of UK Parliament Constituencies Constituency considerations for Argyll and Bute, Highland and Moray council areas Action required 1. The Commission is invited to consider alternative designs of constituencies for Argyll and Bute, Highland and Moray council areas for its initial proposals, in furtherance of its 2018 Review of UK Parliament constituencies. Background 2. On 24 February 2016, the Commission began its 2018 Review of UK Parliament constituencies with a view to making its recommendations by October 2018 in tandem with the other UK parliamentary boundary commissions. 3. The review is being undertaken in compliance with the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended. The Act stipulates a UK electoral quota of 74,769.2 electors and use of the parliamentary electorate figures from the December 2015 Electoral Register. The 5% electorate limits in the Act correspond to an electorate of no less than 71,031 and no more than 78,507. 4. The Act requires the Commission to recommend the name, extent and designation of constituencies in Scotland, of which there are to be 53 in total. 2 Scottish constituencies are prescribed in the Act: Orkney and Shetland Islands constituency and Western isles constituency. 5. The Act provides some discretion in the extent of the Commission’s regard to the size, shape and accessibility of constituencies, existing constituencies and the breaking of local ties. As this review is considered to be the first following enactment of the legislation (the 6th Review was ended before completion in 2013 following enactment of the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013) the Commission need not have regard to the inconveniences attendant on changes to constituencies. -

Traditions of Strathglass. by Colin Chisholm. I

TRADITIONS OF STRATHGLASS. BY COLIN CHISHOLM. I. IN this and the succeeding papers on the traditions of my native glen, I shall only select such legends as truthful and trustworthy people used to recite : Straghlais a chruidh Chininn Cha robh mi ann aiueol, 'S TO mli.it.h b'eol dhomh Gleanncanaich an fheoir. There is an old tradition in Strathglass that all the inhabitants of the name of Ghisholm in the district are descended from a colony of emigrants who left Caithness in troublesome times and located themselves in the Glen. From my earliest recollection I used to hear this story among the people. Some believed, some doubted, and some denied it altogether. In Maclan's sketches of the Highland Clans, there is a short account of the Clan Chisholm and how they settled in the Highlands, by James Logan, F.S.A. Scot, written by him for MacIan when he was a librarian in the British Museum, where he collected the data from which he wrote his admirable history of the "Scottish Gael." Finding the old Strathglass tradition partly, if not wholly substantiated by the following extract from No. 2, page 1, of the joint sketches by Maclan and Logan, let me place it before the reader, that he may judge for himself : — " Harald, or Guthred, Thane of Caithness, nourished in the latter part of the twelfth century. Sir Robert Gordon gives him the surname of Chisholm ; and the probability is, that it was the general name of his followers. He married the daughter of Madach, Earl of Athol, and be came one of the most powerful chiefs in the north, where he created con- tinned disturbances during the reign of William the Lion, by whom he was at last defeated and put to death, his lands being divided between Freskin, ancestor of the Earls of Sutherland, and Manus, or Magnus, son of Gillibreid, Earl of Angus. -

Download History of the Mackenzies

History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie [This book was digitized by William James Mackenzie, III, of Montgomery County, Maryland, USA in 1999 - 2000. I would appreciate notice of any corrections needed. This is the edited version that should have most of the typos fixed. May 2003. [email protected]] The book author writes about himself in the SLIOCHD ALASTAIR CHAIM section. I have tried to keep everything intact. I have made some small changes to apparent typographical errors. I have left out the occasional accent that is used on some Scottish names. For instance, "Mor" has an accent over the "o." A capital L preceding a number, denotes the British monetary pound sign. [Footnotes are in square brackets, book titles and italized words in quotes.] Edited and reformatted by Brett Fishburne [email protected] page 1 / 876 HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. NEW, REVISED, AND EXTENDED EDITION. BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, M.J.I., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CHISOLMS;" "THE PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER;" "THE HISTORICAL "TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" "THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE;" ETC., ETC. LUCEO NON URO INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCXCIV. PREFACE. page 2 / 876 -:0:- THE ORIGINAL EDITION of this work appeared in 1879, fifteen years ago. It was well received by the press, by the clan, and by all interested in the history of the Highlands. -

Beauly and East Kilmorack 1757

1 Title: “A plan of that part of the annexed estate of Lovat lying in the parish of Kilmorack.” National Archive of Scotland ref: RHP6586, a 19th-century lithograph of the original held by West Register House, Charlotte Square, Edinburgh. It consists of 8 c.A2 size sheets; black- and white, but highly legible, except where folds have obscured text (used by Harrison 1998). Location of original: Lovat Estate Office, Beauly, Inverness-shire. Surveyor, Date and Purpose: Peter May, 1757 (date on plan is simply 17, with rest left blank. The date 1757 is that given in Adams 1979, 268); compiled as a requirement of Annexation to the Crown, for the Commissioner to the Forfeited Estates, following the 1745 Jacobite rebellion. Associated references: Adams, I. H (ed.)., 1979, Papers on Peter May Land Surveyor 1749-1793, Scottish History Society, 4th series, vol. 15. Black, R. J., 2000, ‘Scottish Fairs and Fair-Names’, Scottish Studies 33, 1-75. Kilmorack Heritage Association (compiled by H. Harrison) 1998, Urchany and Farley, Leanassie and Breakachy, Parish of Kilmorack 1700-1998, (St Albans; reprinted with corrections Sept. 1999).Parts relating to Urchany and Farley included, but with some transcription errors. Kilmorack Heritage Association, North Lodge, Beauly, Inverness-shire. IV4 7BE e-mail [email protected] or visit website www.kilmorack.com Publications are: Urchany and Farley, Leanassie and Breakachy 1998 The Glens and Straths of Kilmorack 2001 The Village of Beauly 2001 The Braes 2002 Monumental Inscriptions of the Parish of Kilmorack 2002 Monumental Inscriptions of the Parish of Kiltarlity and Convinth 2002 Monumental Inscriptions of the Parish of Kirkhill 2003 Watson, W.J. -

A'chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit

Iain Mac an Tàilleir 2003 1 A'Chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit. "The mouth of the Lednock", an obscure "The cliff or rock", from Norse. name. Abban (Inverness), An t-Àban. Aberlemno (Angus), Obar Leamhnach. “The backwater” or “small stream”. "The mouth of the elm stream". Abbey St Bathans (Berwick). Aberlour (Banff), Obar Lobhair. "The abbey of Baoithean". The surname "The mouth of the noisy or talkative stream". MacGylboythin, "son of the devotee of Aberlour Church and parish respectively are Baoithean", appeared in Dumfries in the 13th Cill Drostain and Sgìre Dhrostain, "the century, but has since died out. church and parish of Drostan". Abbotsinch (Renfrew). Abernethy (Inverness, Perth), Obar Neithich. "The abbot's meadow", from English/Gaelic, "The mouth of the Nethy", a river name on lands once belonging to Paisley Abbey. suggesting cleanliness. Aberarder (Inverness), Obar Àrdair. Aberscross (Sutherland), Abarsgaig. "The mouth of the Arder", from àrd and "Muddy strip of land". dobhar. Abersky (Inverness), Abairsgigh. Aberargie (Perth), Obar Fhargaidh. "Muddy place". "The mouth of the angry river", from fearg. Abertarff (Inverness), Obar Thairbh. Aberbothrie (Perth). "The mouth of the bull river". Rivers and "The mouth of the deaf stream", from bodhar, stream were often named after animals. “deaf”, suggesting a silent stream. Aberuchill (Perth), Obar Rùchaill. Abercairney (Perth). Although local Gaelic speakers understood "The mouth of the Cairney", a river name this name to mean "mouth of the red flood", from càrnach, meaning “stony”. from Obar Ruadh Thuil, older evidence Aberchalder (Inverness), Obar Chaladair. points to this name containing coille, "The mouth of the hard water", from caled "wood", with similarities to Orchill. -

The Highland Clans and the '45 Jacobite Rising

The Highland Clans and the ’45 Jacobite Rising Name: Chantal Duijvesteijn Student number: 3006328 Master Thesis for the University of Utrecht Written under supervision of Pr. Mr. David Onnekink 2009 Chantal Duijvesteijn, 3006328, The Highland Clans and the ’45 Jacobite Rising Index P. Introduction 1 Origins and structure of the Highland Clans 5 Jacobitism and the Rising of ’45 14 Conditions in the 1740’s 24 The Highland Clans and the ’45 31 Case study: Clan Fraser of Lovat 45 Conclusion 59 Appendix 64 Bibliography 66 i Chantal Duijvesteijn, 3006328, The Highland Clans and the ’45 Jacobite Rising Foreword Always, I have been looking to the Napoleonic Era for paper topics and theses. Since I felt this became a bit boring, I decided to explore a different topic for my final thesis. Through Diana Gabaldon’s Voyager Series I became aware of Jacobitism and after finishing reading the novels I decided that was it for me. As the writing of this paper has been ‘the real deal’ and has taken quite some time and effort from multiple parties, I would first of all like to thank Dr. Onnekink for the help, effort and time he spent on me this last year. I felt it very motivating to know there was someone who wanted to push me beyond what I thought I could do and believed I could do better every time. Second, I would like to thank my Martin for the occasional kick in the butt, for being there at the times it seemed there was no light at the end of the tunnel and simply supporting me throughout. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver ....