Traditions of Strathglass. by Colin Chisholm. I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

“Hardwood Development for North Scotland

2017 ICF North Scotland Hardwood Development for North Scotland: Progress & Options Kiltarlity/ Beauly, Inverness-shire - 27th April 2017 Subject Matter This meeting will examine the progress in realising the potential of hardwood trees for timber and woodfuel production in the north of Scotland as well as at options and Research and Development needs for the future. There is a long-standing history of hardwood silviculture (oak, ash, elm, beech. sycamore) on certain private estates in the region. However recent decades have seen a growing perception that hardwoods cannot be grown economically at this latitude (57-59 degN) despite experience to the contrary from Scandinavia and development work by Highland Birchwoods etc. Few hardwood stands in the region have been managed for timber since the 1950’s. Recent increases in demand for estate woodfuel and interest in local/community woodland management have raised the profile of hardwoods. The Forestry Commission aims to manage a proportion of their hardwood resources for timber. We now need to consider what we already know and what more we need to know for the next steps. In the morning session, we have speaker presentations from relevant Forestry Commission and Forest Research staff, and from private consultants. After lunch, we will visit key local private woodlands where hardwoods are being tended for timber. Tea and Coffee will be provided. Attendees must bring their own packed lunch. Venue The morning indoor component of the meeting on Thursday 27th April will be held at Kiltarlity Village Hall near Beauly - 12 miles west of Inverness. Field visits in the afternoon will be to relevant woodland sites in the locality, under private ownership. -

C:\MYDOCU~1\ACCESS~2\Aird\New Aird Inside.Pmd

Wester To Inverness Lovat Kirkhill 6 Kirkhill and Wardlaw Wardlaw 6 Paths Around Beauly Mausoleum Ferry Brae Bogroy A roadside path to the village of Kirkhill and to the burial To Lentran Beauly ground used by the Clan Fraser of Lovat. Robert the Bruce’s The Aird 7 Inchmore chamberlain was Sir Alexander Fraser. His brother, Sir Simon A862 acquired the Bisset Lands around Beauly when he won the hand ! of its heiress, and these lands became the family home. The walk can be extended by following the cycle route as far as Ferry Brae. 1 Newtonhill circuits 1 2 ! Cabrich Approx 5 kms round trip to the Mausoleum (3.1 miles) Moniack Newtonhill Castle Parking at Bogroy Inn or at the Mausoleum This varied circular walk on quiet country roads provides a A833 A Bus service from Inverness and Dingwall to the Bogroy Inn flavour of what the Aird has to offer; agricultural landscape, 5 To Easy - sensible footwear natural woodland, plantations of Scots Pine and mature beech To Kiltarlity Kirkton and magnificent panoramas. The route provides links to the 4 3 Muir other paths in the network. It offers views to the Fannich and Belladrum Mám Mòr To the Affric ranges to the north and west, views to the east down the 8 Reelig Great Moray Firth and some of the best views to Ben Wyvis. The THE AIRD A Glen Glen Way climb from Reelig Glen is worth the effort with the descent via Newtonhill and Drumchardine, a former weaving community A Phoineas Newtonhill Circuit The Cabrich Tourist Information A Access point providing an easy finish. -

Executive Summary NHS Highland Pharmaceutical Care Services Plan 2013-2014

Executive Summary NHS Highland Pharmaceutical Care Services Plan 2013-2014 The NHS (Pharmaceutical Services) (Scotland) Amendment regulations 2011 require NHS Boards to publish pharmaceutical care plans and update them annually. The purpose of this Pharmaceutical Care Services Plan (PCS Plan) is to provide information on the pharmaceutical care services currently available within NHS Highland. This will help us find any potential gaps in service provision and identify where there may be a need for a pharmaceutical service. A secondary function of the plan is to inform and engage members of the public, health professions and planners in the planning of pharmaceutical services. The Pharmacy Practices Committee will use the Board’s PCS Plan when considering applications to join the Pharmaceutical List. The pharmaceutical needs of the local community will be the main determinant of whether an additional community pharmacy or relocation will be approved by them. PCS planning provides a mechanism to determine the number of premises providing NHS pharmaceutical services, by responding as closely as possible to the need of the local population for those services. Boards will develop a pharmaceutical care needs assessment process to assess what pharmaceutical care services are needed by the population; what services are currently provided; define and quantify the gap in service provision and; describe plans to close the gap. The underpinning approach will be a scientific study of population and health. The views and experience of those involved locally in planning and providing pharmaceutical services in particular, and health services in general, are also key to the planning process. This second PCS Plan is mostly narrative in nature with limited gap analysis. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Allt Carach Wind Farm Ltd Land SW of Urchany and Farley Forest, Struy, Beauly

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item 5.8 SOUTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE Report No PLS/039/14 20 May 2014 14/00644/FUL: Allt Carach Wind Farm Ltd Land SW of Urchany and Farley Forest, Struy, Beauly Report by Area Planning Manager - South SUMMARY Description : Erection of temporary 80m high meteorological mast & associated fencing for temporary period of 5 years in relation to the proposed Allt Carach Wind Farm. Recommendation - GRANT Ward : 13 - Aird and Loch Ness Development category : Local Reason referred to Committee : 5 or more objections from members of the public 1. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 1.1 The proposal involves the erection of an 80 metre anemometer mast on land to the south-west of Urchany and Farley Forest. It will be required for a period of up to 5 years to determine the feasibility of the site, including wind speeds, in connection with a proposed wind farm which may be the subject of a separate application at a later date. The mast will be used to mount anemometers (wind measurement devices) and will be held in place by stay lines at four points around the mast. 1.2 The site will take access from the A831 close to Erchless Castle by way of an existing farm track on the estate to Lochan Fada and Loch nan Cuilc. The mast will be located to the north-west of these lochs. 2. SITE DESCRIPTION 2.1 The site lies to the south of Beinn a’Chlaonaidh and occupies an elevated position bounded by a mature plantation to the south-east. The immediate area surrounding the proposal is predominantly rural in character. -

BCS Paper 2016/15 2018 Review of UK Parliament Constituencies Constituency Considerations for Argyll and Bute, Highland and Mora

Boundary Commission for Scotland BCS Paper 2016/15 2018 Review of UK Parliament Constituencies Constituency considerations for Argyll and Bute, Highland and Moray council areas Action required 1. The Commission is invited to consider alternative designs of constituencies for Argyll and Bute, Highland and Moray council areas for its initial proposals, in furtherance of its 2018 Review of UK Parliament constituencies. Background 2. On 24 February 2016, the Commission began its 2018 Review of UK Parliament constituencies with a view to making its recommendations by October 2018 in tandem with the other UK parliamentary boundary commissions. 3. The review is being undertaken in compliance with the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended. The Act stipulates a UK electoral quota of 74,769.2 electors and use of the parliamentary electorate figures from the December 2015 Electoral Register. The 5% electorate limits in the Act correspond to an electorate of no less than 71,031 and no more than 78,507. 4. The Act requires the Commission to recommend the name, extent and designation of constituencies in Scotland, of which there are to be 53 in total. 2 Scottish constituencies are prescribed in the Act: Orkney and Shetland Islands constituency and Western isles constituency. 5. The Act provides some discretion in the extent of the Commission’s regard to the size, shape and accessibility of constituencies, existing constituencies and the breaking of local ties. As this review is considered to be the first following enactment of the legislation (the 6th Review was ended before completion in 2013 following enactment of the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013) the Commission need not have regard to the inconveniences attendant on changes to constituencies. -

The Rivers of Scotland: the Beauly and Conon

Scottish Geographical Magazine ISSN: 0036-9225 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsgj19 The rivers of Scotland: The Beauly and Conon Lionel W. Hinxman B.A., F.R.S.E. To cite this article: Lionel W. Hinxman B.A., F.R.S.E. (1907) The rivers of Scotland: The Beauly and Conon, Scottish Geographical Magazine, 23:4, 192-202, DOI: 10.1080/00369220708733740 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00369220708733740 Published online: 27 Feb 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 10 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsgj20 Download by: [ECU Libraries] Date: 05 June 2016, At: 10:02 192 SCOTTISH GEOGRAPHICAL MAGAZINE THE RIVERS OF SCOTLAND: THE BEAULY AND CONON. By LIONEL W. HINXMAN, B.A., F.R.S.E. (With Map and Diagrams.) UNLIKE the Spey and other large streams of the north-east coast south of the Moray Firth—rivers of simple type in which the tributaries are throughout distinctly subordinate to the main stream—the Beauly and the Conon are examples of a complex river system, formed of several large streams nearly equal in length and volume, and confluent at a comparatively short distance above the river mouth. This character is most marked in the case of the Beauly, and is indeed apparent in the nomenclature of the river system. The Affric, the Cannich, and the Farrar, streams of almost equal volume, unite to form the river Glass, -which at some indeterminate point in its course between Struy and Eilean Aigas ceases to bear that name and flows to the sea as the Beauly River.1 The apparent redundancy in the name Glen Strath Farrar now given to the valley of the Farrar, may possibly be accounted for when we remember that the Beauly Firth was the JEstuarium Fararum of the early geographers, the estuary of the Varar—that name being evidently applied to the whole of the Farrar-Beauly river. -

Download History of the Mackenzies

History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie [This book was digitized by William James Mackenzie, III, of Montgomery County, Maryland, USA in 1999 - 2000. I would appreciate notice of any corrections needed. This is the edited version that should have most of the typos fixed. May 2003. [email protected]] The book author writes about himself in the SLIOCHD ALASTAIR CHAIM section. I have tried to keep everything intact. I have made some small changes to apparent typographical errors. I have left out the occasional accent that is used on some Scottish names. For instance, "Mor" has an accent over the "o." A capital L preceding a number, denotes the British monetary pound sign. [Footnotes are in square brackets, book titles and italized words in quotes.] Edited and reformatted by Brett Fishburne [email protected] page 1 / 876 HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. NEW, REVISED, AND EXTENDED EDITION. BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, M.J.I., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CHISOLMS;" "THE PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER;" "THE HISTORICAL "TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" "THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE;" ETC., ETC. LUCEO NON URO INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCXCIV. PREFACE. page 2 / 876 -:0:- THE ORIGINAL EDITION of this work appeared in 1879, fifteen years ago. It was well received by the press, by the clan, and by all interested in the history of the Highlands. -

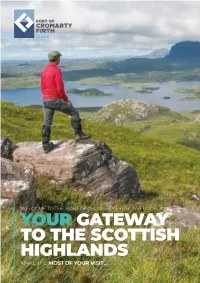

Your Gateway to the Scottish Highlands Make the Most of Your Visit

Welcome to the Port of cromarty firth, invergordon Your GatewaY to the ScottiSh hiGhlandS make the Most of Your Visit... The Invergordon Mural Trail Cover photo : Typical Highland scenery. Photo © VisitScotland / Kenny Lam 2 fàilte WELCOME from thE Port aND thE rESiDENtS of iNVErGorDoN it’s an honour and privilege to welcome you respected courses – royal Dornoch, fortrose, to invergordon, on the shores of the beautiful tain and Castle Stuart. ride the Strathspey Cromarty firth. Steam railway or explore the Cairngorms National Park and inverewe Gardens…and of the Cromarty firth is your gateway to the course, you can discover for yourselves the majestic Scottish highlands. With over 85 truth behind the famous ‘Nessie’ legend. different shore excursion options, you are guaranteed to find an authentic Highland Whilst a day is never long enough in the experience from invergordon. Experience rich, Highlands, this guide aims to ensure you find Scottish history at the Castles of Dunrobin, your own memorable experience, so you can mey, Cawdor, Eilean Donan and Urquhart. make the most of your time and will hopefully Play golf on Scotland’s oldest and most want to come back and visit us again. Allison McGuire George Carson Cruise manager, Port of Cromarty firth Chairman, invergordon tourism alliance Port of Cromarty firth | YOUR GATEWAY TO THE HIGHLANDS 3 C’est un honneur et un privilège de vous accueillir à Invergordon, sur les rivages du magnifique Cromarty Firth Le Cromarty Firth est votre porte d’entrée vers Cairngorms et les jardins d’Inverewe ... et les la majestueuse région des Highlands écossais. -

Parish Profile Parish Erchless

Scottish Charity Number: SC 008121 Kilmorack and Parish Profile Erchless photograph: looking across the river to Struy Church The Parish of Kilmorack and Erchless The parish is in one of the most beautiful parts of Scotland and centres around the historic and picturesque village of Beauly which is 12 miles west from Inverness and 9 miles south of Dingwall. The two other places of worship are Struy, 10 miles south west from Beauly, and Cannich, 7 miles further up Strathglass, en route to Glen Affric. Kilmorack East Church, known also as Beauly Church The Church is located on Croyard Road, Beauly. Struy Church Struy Church is located on the left side of the road, 10 miles from Beauly on the A831, about 100 m before you reach the village of Struy. Cannich Church The Church is located in the village of Cannich. Approaching Cannich from Beauly on the A 831, turn right after crossing the bridge and proceed about 50 m up the hill where you will find the Church on the right hand side. St Columba Hall St Columba Hall is an excellent facility next to the Beauly Church. 2 Church Services Information Model Constitution; 10 elders, around 200 members and adherents. Services Beauly - weekly, at 11.30 am Struy and Cannich - alternate - at 10 am Communion Services Beauly :-lst Sunday of March, July and November Beauly Church Struy: May Cannich : October 5th Sunday service There is a combined service using each Church by turn. This is followed by a picnic lunch (weather permitting.) combined service picnic at Cannich Other Information: There is a welcome area at the back of the Church in Beauly, which is also suitable for parents with young children.