The Highland Clans and the '45 Jacobite Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

) Division Yours Faithfully, GARY GILLESPIE Chief Economist

Chief Economist Directorate Office of the Chief Economic Adviser (OCEA) Division <<Name>> <<Organisation>> <<Address 1>> <<Address 2>> <<Address 3>> <<Address 4>> <<Address 5>> URN: Dear << Contact >> Help us make decisions to help businesses trade locally and internationally I am writing to ask you to take part in the 20172016 ScottishScottish GlobalGlobal ConnectionsConnections SurveySurvey.. ThisThis isis the only official trade survey for Scotland, undertaken in partnership with Scottish Development International. This survey measures key indicators on the state of the Scottish economy. It helps us to measure the value and destination of sales of Scottish goods and services and the depth of international involvement of Scottish firms. To make sure the results are accurate, all types and sizes of organisation are included in the sample for this survey, including those businesses whose head offices are located outside Scotland. Even if you have no international connections, your response is still valuable to us. Once completed, please return the survey in the enclosed pre-paid envelope. Your response is appreciated by XXXXXXXXXFriday 22nd September. All information 2017 you. All provide information will be you kept provide completely will be confidential. kept Ifcompletely you have confidential.any queries please If you emailhave [email protected] queries please contact our. Alternatively helpline on you0131 can 244 contact 6803 or thee-mail helpline [email protected]. on 0131 244 6803 between 10am and 4pm. Please note you can also reply electronically. Further information can be found at: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Economy/Exports/GCSElectReturn. Thank you in advance for your cooperation. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

C:\MYDOCU~1\ACCESS~2\Aird\New Aird Inside.Pmd

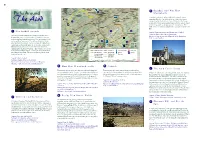

Wester To Inverness Lovat Kirkhill 6 Kirkhill and Wardlaw Wardlaw 6 Paths Around Beauly Mausoleum Ferry Brae Bogroy A roadside path to the village of Kirkhill and to the burial To Lentran Beauly ground used by the Clan Fraser of Lovat. Robert the Bruce’s The Aird 7 Inchmore chamberlain was Sir Alexander Fraser. His brother, Sir Simon A862 acquired the Bisset Lands around Beauly when he won the hand ! of its heiress, and these lands became the family home. The walk can be extended by following the cycle route as far as Ferry Brae. 1 Newtonhill circuits 1 2 ! Cabrich Approx 5 kms round trip to the Mausoleum (3.1 miles) Moniack Newtonhill Castle Parking at Bogroy Inn or at the Mausoleum This varied circular walk on quiet country roads provides a A833 A Bus service from Inverness and Dingwall to the Bogroy Inn flavour of what the Aird has to offer; agricultural landscape, 5 To Easy - sensible footwear natural woodland, plantations of Scots Pine and mature beech To Kiltarlity Kirkton and magnificent panoramas. The route provides links to the 4 3 Muir other paths in the network. It offers views to the Fannich and Belladrum Mám Mòr To the Affric ranges to the north and west, views to the east down the 8 Reelig Great Moray Firth and some of the best views to Ben Wyvis. The THE AIRD A Glen Glen Way climb from Reelig Glen is worth the effort with the descent via Newtonhill and Drumchardine, a former weaving community A Phoineas Newtonhill Circuit The Cabrich Tourist Information A Access point providing an easy finish. -

An Introduction to Policy in Scotland

POLICY GUIDE #1 2019 AN INTRODUCTION TO POLICY IN SCOTLAND This first guide provides an introduction to policymaking BES – SCOTTISH POLICY in Scotland, how policies are developed, and the difference GROUP between policy and legislation. Subsequent guides will focus on how scientists can get involved in the policy process The BES Scottish Policy Group at Holyrood and the various opportunities for evidence (SPG) is a group of British Ecological Society (BES) submission, such as to Scottish Parliament Committees. members promoting the use To find out about the policy making process at Westminster of ecological knowledge in please read the BES UK Policy Guides. Scotland. Our aim is to improve communication between BES members and policymakers, increase the impact of ecological research, and support evidence- WHAT IS A POLICY? EXAMPLES OF POLICY informed policymaking. We engage with policymaking A policy is a set of principles to Details of a policy and the steps by making the best scientific guide actions in order to achieve an needed to meet the policy ambitions evidence accessible to objective. A ‘government policy’, are often specified in Government decision-makers based on our therefore describes a course of strategies, which are usually membership expertise. action or an objective planned by developed through stakeholder the Government on a particular engagement – (i.e. Government Our Policy Guides are a resource subject. Documentation on Scottish consultations). These strategies are for scientists interested in Government policies is publicly non-binding but are often developed the policymaking process available through the Scottish to help meet binding objectives, for in Scotland and the various Government website. -

Itinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart from His

PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME XXIII SUPPLEMENT TO THE LYON IN MOURNING PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART ITINERARY AND MAP April 1897 ITINERARY OF PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART FROM HIS LANDING IN SCOTLAND JULY 1746 TO HIS DEPARTURE IN SEPTEMBER 1746 Compiled from The Lyon in Mourning supplemented and corrected from other contemporary sources by WALTER BIGGAR BLAIKIE With a Map EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1897 April 1897 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A List of Authorities cited and Abbreviations used ................................................................................. 8 ITINERARY .................................................................................................................................................. 9 ARRIVAL IN SCOTLAND .................................................................................................................. 9 LANDING AT BORRADALE ............................................................................................................ 10 THE MARCH TO CORRYARRACK .................................................................................................. 13 THE HALT AT PERTH ..................................................................................................................... 14 THE MARCH TO EDINBURGH ...................................................................................................... -

A Colonial Scottish Jacobite Family

A COLONIAL SCOTTISH JACOBITE FAMILY THE ESTABLISHMENT IN VIRGINIA OF A BRANCH OF THE HUM-ES of WEDDERBURN Illustrated by Letters and Other Contemporary Documents By EDGAR ERSKINE HUME M. .A... lL D .• LL. D .• Dr. P. H. Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Member of the Virginia and Kentucky Historical Societies OLD DoKINION PREss RICHMOND, VIRGINIA 1931 COPYRIGHT 1931 BY EDGAR ERSKINE HUME .. :·, , . - ~-. ~ ,: ·\~ ·--~- .... ,.~ 11,i . - .. ~ . ARMS OF HUME OF WEDDERBURN (Painted by Mr. Graham Johnston, Heraldic Artist to the Lyon Office). The arms are thus recorded in the Public ReJ?:ister of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland (Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms) : Quarterly, first and fourth, Vert a lion rampant Argent, armed and langued Gules, for Hume; second Argent, three papingoes Vert, beaked and membered Gules, for Pepdie of Dunglass; third Argent, a cross enirrailed Azure for Sinclair of H erdmanston and Polwarth. Crest: A uni corn's head and neck couped Argent, collared with an open crown, horned and maned Or. Mottoes: Above the crest: Remember; below the shield: True to the End. Supporters: Two falcons proper. DEDICATED To MY PARENTS E. E. H., 1844-1911 AND M. S. H., 1858-1915 "My fathers that name have revered on a throne; My fathers have fallen to right it. Those fathers would scorn their degenerate son, That name should he scoffingly slight it . " -BORNS. CONTENTS PAGE Preface . 7 Arrival of Jacobite Prisoners in Virginia, 1716.......... 9 The Jacobite Rising of 1715. 10 Fate of the Captured Jacobites. 16 Trial and Conviction of Sir George Hume of Wedder- burn, Baronet . -

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots Chief’s Message Summer 2021 Issue I am delighted that summer is upon us finally! For a while there I thought winter was making a comeback. I hope this finds you all well and excited to get back to a more normal lifestyle. We are excited as we will finally get to meet in person for our Annual Meeting and Gathering of the Clans in August and hope you all make an effort to come. We haven't seen you all in over a year and a half and we are looking forward to your smiling faces and a chance to talk with all of you. Covid-19 has been rough on all of us; it has been a horrible year plus. But the officers of the Society have been meeting on a regular basis trying hard to keep the Society going. Now it is your turn to come and get involved once again. After all, a Society is not a society if we don't gather! Make sure to mark your calendar for August 7th, put on your best Tartan and we will see you then. As Aye, Helen Jacobsen Gathering of the Clans :an occasion when a large group of family or friends meet, especially to enjoy themselves e.g., Highland Games. See page 5 for info about our Annual Meeting & Gathering of the Clans See page 15 for a listing of some nearby Gatherings Click here for Billy Raymond’s song “The Gathering of the Clans” To remove your name from our mailing list, The Scottish Society of Nebraska please reply with “UNSUBSCRIBE” in the subject line. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Line of March

NYC TARTAN DAY PARADE - April 8, 2017 LINE OF MARCH FIRST DIVISION: West 44th Street from 6th Avenue to 5th Avenue Section 1: Forms from corner of 6th Avenue East to 59 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Mounted Unit (forms on 6th Avenue above W. 45th Street) 2. U.S. Military Academy (West Point) Pipes and Drums 3. Grand Marshal Banner 4. Grand Marshal Tommy Flanagan (with family/friends ) 5. St. Andrew’s Color Guard 6. NTDNYC Banner 7. Edinburgh Academy Pipe and Drum Band 8. National Tartan Day New York Parade Committee 9. BARBOUR 10. U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) Pipes and Drums 11. VIPs: 12. Scottish Parliament/Politicians/U.S. Politicians 13. Visit Scotland Section 2: Forms from 59 West 44th Street to 37 West 44th Street 1. Mt. Kisco Scottish Pipes and Drums 2. St. Andrew’s Society of New York 3. New York Caledonian Club Pipe Band 4. New York Caledonian Club 5. New York Metro Pipe Band 6. American Scottish Foundation 7. Bucks County Scottish American Society 8. Stephen P. Driscoll Memorial Pipe Band 9. Clan Campbell 10. Daughters of Scotia 11. St. Andrew’s Society; City of Albany 12. Middlesex County Police and Fire Pipes and Drums 13. Shot of Scotch Dancers 14. Flings and Things Dancers - 1 - Section 3: Forms from 37 West 44th Street to 27 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Marching Band 2. CARNEGIE HALL 3. Carnegie Mellon Alumni 4. Clan Malcolm/MacCallum 5. Clan Ross of U.S. 6. Tri-County Pipes and Drums 7. Long Island Curling Club 8. -

Discovering Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites

DISCOVERING BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE & THE JACOBITES NATIONAL MUSEUM PALACE OF EDINBURGH STIRLING KILLIECRANKIE ALLOA TOWER LINLITHGOW OF SCOTLAND HOLYROODHOUSE CASTLE CASTLE PALACE DOUNE CASTLE The National Trust for Scotland HUNTINGTOWER Historic Scotland CASTLE National Museum of Scotland Palace of Holyroodhouse CULLODEN BATTLEFIELD Thurso BRODIE CASTLE Lewis FORT GEORGE Ullapool Harris Poolewe North Fraserburgh Uist Cromarty Brodie Castle URQUHART A98 Benbecula Fort George A98 CASTLE A947 Nairn A96 South Uist Fyvie Castle Skye Kyle of Inverness Culloden Huntly Lochalsh Battlefield Kildrummy A97 Leith Hall Barra Urquhart Castle Canna Castle DRUM CASTLE A887 A9 Castle Fraser A944 A87 Kingussie Corgarff Aberdeen Rum Glenfinnan Castle Craigievar Drum Monument A82 Castle A830 A86 Eigg Castle Fort William A93 A90 A92 A9 House Killiecrankie of Dun FYVIE CASTLE A861 Glencoe Pitlochry A924 Montrose Tobermory A933 A82 Glamis Dunkeld Craignure Dunstaffnage Castle A827 A822 Dundee Staffa Burg A92 Mull A85 Crianlarich Perth Huntingtower CASTLE FRASER Iona Oban A85 Castle A9 St Andrews M90 Doune Castle Alloa Tower Stirling Castle Stirling Helensburgh A811 Edinburgh Tenement M80 CRAIGIEVAR House Glasgow CASTLE Linlithgow A8 Dumbarton Edinburgh Palace A1 Glasgow Castle M8 A74 A7 Berwick M77 EdinburghA68 M74 Pollok House Ardrossan A737 A736 Castle M74 A72 A83 National Palace of LEITH HALL A726 Holmwood A749 A841 Museum of Holyroodhouse Ayr Scotland Greenbank Garden A725 A68 Moffat DUMBARTON DUNSTAFFNAGE GLENFINNAN GLENCOE HOUSE OF DUN CORGARFF KILDRUMMY CASTLE CASTLE MONUMENT Dumfries CASTLE CASTLE Stranraer Kirkcudbright The Palace of Holyroodhouse image: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016. Photographer: Sandy Young DISCOVERING BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE & THE JACOBITES The story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) and the Jacobites is embedded in Scotland’s rich and turbulent history, resonating across the centuries. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction.