The School Textbook and the People's Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publishing in the Nineteenth Century

1 Publishing in the Nineteenth Century Originally published as “Editer au XIXe siècle”, Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France, vol. 107, no. 4, 2007, pp. 771–90. Introduction When Roger Chartier and Henri-Jean Martin were preparing the introduction to the first volume of their monumental Histoire de l’Édition francaise (History of French publishing), which they entitled Le livre conquérant. Du Moyen Age au milieu du XVIIe siècle (The Conquering Book. From the Middle Ages to the mid-seventeenth century), they encountered a problem – one might even call it an aporia. They explained their twin debt both to Lucien Febvre, the initiator of research into the history of the book,1 and to Jean-Pierre Vivet, a journalist turned director of Promodis Publishing, who had expressed his desire to “see [the publisher] placed at the center of these four volumes,” which he had entrusted to them.2 This outspoken directive implied that the figure of the publisher long predated the invention of printing, and that he had been performing the role of broker or mediator without interruption from the thirteenth up to the twentieth century, as is the case today. The two editors were very well aware that sustaining such a notion could prove risky, and so they added this further comment, which partly contradicted what had gone before: The story we would like to tell is one in which the role of the publisher was gradually asserted and became more clearly defined; he was bold in the age of the conquering 1 Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, L’apparition du livre (Paris: Albin Michel, 1958), translated into English as The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800 (London: Verso, 1976). -

Reference Document Including the Annual Financial Report

REFERENCE DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2012 PROFILE LAGARDÈRE, A WORLD-CLASS PURE-PLAY MEDIA GROUP LED BY ARNAUD LAGARDÈRE, OPERATES IN AROUND 30 COUNTRIES AND IS STRUCTURED AROUND FOUR DISTINCT, COMPLEMENTARY DIVISIONS: • Lagardère Publishing: Book and e-Publishing; • Lagardère Active: Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage; • Lagardère Services: Travel Retail and Distribution; • Lagardère Unlimited: Sport Industry and Entertainment. EXE LOGO L'Identité / Le Logo Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins Echelle: d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. Agence d'architecture intérieure LAGARDERE - Concept C5 - O’CLOCK Optimisation Les entrepreneurs devront s’engager à executer les travaux selon les règles de l’art et dans le respect des règlementations en vigueur. Ce 15, rue Colbert 78000 Versailles Date : 13 01 2010 dessin est la propriété de : VERSIONS - 15, rue Colbert - 78000 Versailles. Ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation. tél : 01 30 97 03 03 fax : 01 30 97 03 00 e.mail : [email protected] PANTONE 382C PANTONE PANTONE 382C PANTONE Informer, Rassurer, Partager PROCESS BLACK C PROCESS BLACK C Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la Echelle: Agence d'architecture intérieure solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. -

Dictionnaire Du Compagnonnage Du Même Auteur

DICTIONNAIRE DU COMPAGNONNAGE DU MÊME AUTEUR : - Carcassonne La Palme des Beaux Arts, ou le Tour de France d'un Compagnon Menuisier au XIX siècle, C.N.D.P., 1979. (épuisé) - Compagnonnages d'hier et d'aujourd'hui, C.N.D.P., 1980. (épuisé) - Sur le chemin des Compagnons, éditions de Poliphile, 1984. (épuisé) - « Le Compagnonnage aujourd'hui », chapitre historique in Revue La France, 1986. — Le Tour de France de Jean Bellegarde, Compagnon Charpentier du Devoir (Dessins de Mor), éditons Belisane, 1988. (épuisé) – Agricol Perdiguier dit Avignonnais la Vertu, Compagnon Menuisier du Devoir de Liberté (Dessins de Mor), éditions Bélisane), 1989. (épuisé) - Le Compagnonnage, Jacques Grancher Editeur (Collection Ouverture), 1989. — Voyages dans le Compagnonnage, éditions de Mortagne, 1991. • Couverture : Le Siège de Rhodes (voir notice du Dictionnaire). • Les lettrines sont issues de la Divine Proportion de Fra Luca Pacioli di Boryo San Sepolcro, rééditée par La Librairie du Compagnonnage, Paris, 1980. • Les treize illustrations de cet ouvrage sont de Jules Noël, elles parurent pour la première fois dans L'Illustration en novembre 1945. DICTIONNAIRE DU COMPAGNONNAGE François ICHER Editions du BORRÉGO Si vous désirez être tenu régulièrement au courant de nos parutions, il vous suffit d'envoyer vos nom et adresse aux Editions du Borrégo, BP 37 - 72001 Le Mans cédex. © Editions du Borrégo - 72001 Le Mans, 1992. ISBN : 2-904724-16-8 A Marie et Guillaume Pourquoi un dictionnaire du compagnonnage Un dictionnaire est un recueil de mots d'une langue, rangés dans un ordre en général alphabétique et suivis de leurs défi- nitions. Une encyclopédie est un ouvrage abritant un choix de mots, ce choix se rapportant à un secteur particulier du savoir humain. -

Pdf) UPCOMING EVENTS

lettre_GB_april2005.qxd 15/06/05 16:10 Page 1 “Where there's a will, we pave the way” LETTERTO OUR SHAREHOLDERS SEMESTRAL LETTER - APRIL 2005 EDITORIAL SUMMARY ■ Highlights p. 02 Solid growth in operating income, 2004 Annual Results strong progress at Hachette Livre ■ Hachette Filipacchi Médias p. 03 China Awakens ■ Hachette Livre p. 04 ■ Guinness World Records With effect from January 1, 2004, we have consolidated the Editis assets that we were able to celebrates its 50th birthday retain: Larousse, Dalloz, Dunod and Armand Colin in France, Chambers and Harraps in the UK, Celebrating the Sciences Bécassine and Anaya in Spain. This contributed an extra €342m to 2004 net sales. ■ Hachette Distribution Services p. 05 ■ Hodder Headline (UK), acquired from WH Smith in September 2004, has been consolidated Aelia Abroad The Great Canadian News since October 1, 2004, adding €61m to 2004 net sales. The 35th Virgin Megastore opens ■ The pace of growth in operating income remained very robust, both for the Books division (19.7% growth, before the impact of Editis and Hodder Headline) and Lagardere Active (80%). ■ Lagardere Active p. 06 Lagardere Active channels These were exceptional performances, made possible by strong growth in General Literature and Action! BlingTones, sound and light Part-Works in the Books division and by a surge in radio/TV advertising and restructuring mea- ■ EADS p. 07 sures at Lagardere Active. The contribution from the Distribution division rose by 6.7%. 2004 Annual Results ■ Our aggressive launch policy (Public and Choc), coupled with tough market conditions in Official presentation of the A380 France and Italy, affected operating income in the Press Division, which fell by 2.3% on a reported ■ Shareholders' Notebook p. -

Si La Lecture D'un Manuel Universitaire Peut Paraître Aride (Accompagné D

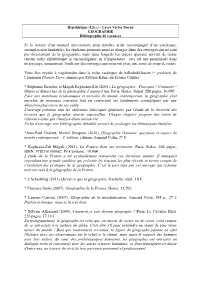

Hypokhâgne (LS1/2) – Lycée Victor Duruy GEOGRAPHIE Bibliographie de vacances Si la lecture d’un manuel universitaire peut paraître aride (accompagné d’un astérisque, exemples non limitatifs), les étudiants pourront aussi se plonger dans des ouvrages qui ne sont pas directement de la géographie, mais dans lesquels les enjeux spatiaux servent de trame (aucun ordre alphabétique ni chronologique, ni d’importance : ceci est une promenade dans un paysage, uniquement fondé sur des ouvrages qui nous ont plus, une sorte de coup de cœur). Vous êtes invités à vagabonder dans le riche catalogue de balladodiffusion (= podcast) de l’émission Planète Terre, animée par Sylvain Kahn, sur France Culture. * Stéphanie Beucher et Magali Reghezza-Zitt (2005), La géographie : Pourquoi ? Comment ? Objets et démarches de la géographie d’aujourd’hui, Paris, Hatier, Initial. 288 pages, 10,69€ Face aux mutations économiques et sociales du monde contemporain, la géographie s'est enrichie de nouveaux concepts tout en confortant ses fondements scientifiques par une définition plus claire de ses outils. L'ouvrage présente tant les réflexions théoriques générales que l'étude de la diversité des terrains que la géographie aborde aujourd'hui. Chaque chapitre propose des textes de référence ainsi que l'analyse d'une notion-clé. En fin d'ouvrage, une bibliographie détaillée permet de prolonger les thématiques étudiées. *Jean-Paul Charvet, Michel Sivignon (2016), Géographie Humaine, questions et enjeux du monde contemporain – 3e édition, éditions Armand Colin, 27 €. * Reghezza-Zitt Magali (2011), La France dans ses territoires, Paris, Sedes. 244 pages, ISBN: 9782301000682. Prix unitaire : 19,90€ L’étude de la France a été profondément renouvelée ces dernières années. -

Pascal Boniface

LISTE COMPLÈTE DES OUVRAGES D E PASCAL BONIFACE 1. 1986 LA PUCE, LES HOMMES ET LA BOMBE : L’EUROPE FACE AUX NOUVEAUX DEFIS TECHNOLOGIQUES ET MILITAIRES En collaboration avec François HEISBOURG. Préface d’André Fontaine. Hachette, 1986, 321 p. Prix Amiral Castex 1987, décerné par la Fondation pour les Etudes de Défense Nationale 2. 1989 LES SOURCES DU DESARMEMENT Préface d’Alain PELLET Economica, Paris, 1989, 263 p. 3. 1990 L’ARMEE, ENQUÊTE SUR 300.000 SOLDATS MECONNUS Editions n° 1, 1990, 310 p. 4. 1992 VIVE LA BOMBE ! « ELOGE DE LA DISSUASION NUCLEAIRE » Editions n° 1, 1992, 177 p. 5. 1994 MANUEL DES RELATIONS INTERNATIONALES Dunod, 1994, 248 p. 6. 1994 LES ÉCOLOGISTES ET LA DEFENSE En collaboration avec Jean-François GRIBINSKI IRIS-Dunod, 1994, 182 p. 1995 - 2ÈME ÉDITION MANUEL DES RELATIONS INTERNATIONALES Dunod [Rééd], 1995, 265 p 7. 1996 LA VOLONTÉ D’IMPUISSANCE : LA FIN DES AMBITIONS INTERNATIONALES ET STRATÉGIQUES Seuil, 1996, 200 p. > Traduit en perse, Editions Shabeer and company, Printing press, 1996. > Traduit en anglais, Queen’s University Press, Kingston, Canada, 1998, 157 p. > Traduit en turc, Edition Yapikredi Yayinlari, Istanbul 1997. > Traduit en arabe, El Aalam El Taleh, le Caire 1997 8. 1996 LES RELATIONS EST-OUEST 1945-1991 Mémo Seuil, 1996, 64 p. > Traduit en roumain, Institut européen, 1999 9. 1997 REPENSER LA DISSUASION NUCLEAIRE Editions de l’aube, 1997, 212 p. 10. 1997 1 LES RELATIONS INTERNATIONALES DEPUIS 1945 Editions Hachette supérieur, 1997, 160 p. 11. 1998 CONTRE LE RÉVISIONNISME NUCLÉAIRE Ellipses, 1998, 128 p. 12. 1998 LA FRANCE EST-ELLE ENCORE UNE GRANDE PUISSANCE ? Presses de Science-Po., 1998, 140 p. -

Representing Territories

CALL FOR PAPERS 4th international conference of the Collège international des sciences du territoire (CIST) Representing territories 22&23 March 2018 Université de Rouen Normandie, France After three conferences that have successively sought to define and lay the foundations for territorial sciences, to go beyond disciplinary frontiers and boundaries, namely through interdisciplinary collaboration, and to explore territorial social demand, the 4th CIST conference aims at mobilising the territorial sciences to address the question of representation. The objective of the conference, which will comprise 17 sessions, is to determine the contribution of the representational approach to the analysis of territories from a theoretical, methodological and empirical point of view. Analyses of representations have their origins in different disciplinary fields, particularly psychology, and have spread throughout the human sciences so that today they are used in a wide variety of contexts by geographers, sociologists, historians and specialists in the political and legal sciences. Both the concept of territory and that of representation, on account of their polysemy, provide the opportunity to bring together different topics, methods and disciplines. The conference is open to every type of representation: concepts, ideas, frameworks, maps, texts, still or animated images, databases, and multimedia vectors used in the context of the construction, development and transformation of territories. Similarly, a wide variety of sources may be used: surveys, interviews, biographies, testimonies, legal, political and cultural documents, plans, programmes, projects or dreams, artistic productions, advertising, social or campaign materials, canonical works, transient footprints on social networks, etc. The most important aspect will be the possibility of using empirical material likely to provide useful input to scientific debates on the role of representations in the territorialisation of societies. -

Histoire Illustrée Du Second Empire (Nouvelle Édition) Par Taxile Delord

Histoire illustrée du Second Empire (Nouvelle édition) par Taxile Delord,... Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France Delord, Taxile (1815-1877). Auteur du texte. Histoire illustrée du Second Empire (Nouvelle édition) par Taxile Delord,.... 1880- 1883. 1/ Les contenus accessibles sur le site Gallica sont pour la plupart des reproductions numériques d'oeuvres tombées dans le domaine public provenant des collections de la BnF. Leur réutilisation s'inscrit dans le cadre de la loi n°78-753 du 17 juillet 1978 : - La réutilisation non commerciale de ces contenus est libre et gratuite dans le respect de la législation en vigueur et notamment du maintien de la mention de source. - La réutilisation commerciale de ces contenus est payante et fait l'objet d'une licence. Est entendue par réutilisation commerciale la revente de contenus sous forme de produits élaborés ou de fourniture de service. CLIQUER ICI POUR ACCÉDER AUX TARIFS ET À LA LICENCE 2/ Les contenus de Gallica sont la propriété de la BnF au sens de l'article L.2112-1 du code général de la propriété des personnes publiques. 3/ Quelques contenus sont soumis à un régime de réutilisation particulier. Il s'agit : - des reproductions de documents protégés par un droit d'auteur appartenant à un tiers. Ces documents ne peuvent être réutilisés, sauf dans le cadre de la copie privée, sans l'autorisation préalable du titulaire des droits. - des reproductions de documents conservés dans les bibliothèques ou autres institutions partenaires. Ceux-ci sont signalés par la mention Source gallica.BnF.fr / Bibliothèque municipale de ... (ou autre partenaire). -

Annuaire D'éditeurs Français 2018

ANNUAIRE D’ÉDITEURS FRANÇAIS 2018 2018 DIRECTORY OF FRENCH PUBLISHERS Bureau international de l’édition française 115, bd Saint-Germain - 75006 Paris, France t. +33 (0)1 44 41 13 13 - f. +33 (0)1 46 34 63 83 [email protected] - www.bief.org ANNUAIRE D’ÉDITEURS FRANÇAIS 2018 2018 DIRECTORY OF FRENCH PUBLISHERS PROMOUVOIR L’ÉDITION FRANÇAISE À L’ÉTRANGER Depuis 140 ans, le BIEF est l’outil de promotion de l’édition française à l’étranger. Organisme professionnel, il regroupe 280 maisons d’édition et bénéficie notamment de l’appui du Centre national du livre. Son programme d’activité s’articule autour de cinq types d’actions : - La participation à des foires internationales du livre, - La publication de catalogues bilingues, outils d’information sur les livres français, - La réalisation d’études et d’organigrammes sur des marchés du livre dans le monde, - L’organisation de rencontres et d’échanges entre professionnels du livre, - La formation et la mise en réseau d’éditeurs et de libraires du monde entier. Cet annuaire présente les adhérents du BIEF. Il permet aux professionnels étrangers de disposer des coordonnées des personnes en charge de l’international – droits étrangers, export, droits audiovisuels – dans chaque maison d’édition ainsi que les domaines éditoriaux publiés. nb : Cet annuaire regroupe les adhérents du BIEF au 10 janvier 2018. Les informations présentées proviennent directement des éditeurs. PROMOTING FRENCH PUBLISHING AROUND THE WORLD For the last 140 years, the BIEF has been promoting French publishers’ internationally. This organization of and for industry professionals, has 280 publishing company members and is funded in part by the Centre National du Livre. -

Rixes Compagnonniques En Eure-Et-Loir (Xixe S)

La rixe - L’Illustration, journal universel, numéro du 29 novembre 1845. Rixes compagnonniques en Eure-et-Loir (XIXe s). par Brix Pivard La première moitié du XIXe siècle est synonyme pour les compagnonnages1 d’interdictions, de concurrences, d’évolutions, d’adaptations, de remises en question, de surveillances policières, de grèves2, de violences3. Jusqu’à l’autorisation de l’existence des syndicats, par la Loi Waldeck-Rousseau en 1884, les compagnonnages demeurent le premier organe de défense des ouvriers. De nombreux corps de métiers qui n’appartiennent pas aux compagnonnages vont emprunter et adopter les formes et les modèles compagnonniques. Cela entraîne des scissions, des divisions et des conflits. Chartres, qui est une ville de compagnonnage4 et de Devoir5 bien qu’il s’agisse d’une ville d’importance secondaire6 sur le Tour de France7, va connaître ces événements. La cote 10 M 38 consultable aux Archives départementales de l’Eure-et-Loir, comporte des rapports, des corres- pondances, des interrogatoires. Ces archives publiques et administratives qui émanent des auto- rités (préfet, sous-préfets, maires, commissaires de polices, etc.) sont des pièces de circonstance. Elles permettent de supposer ce qu’a pu en penser la société au moment des faits. Dans cet article, je chercherai à présenter comment s’est manifestée cette période de trouble pour les compagnonnages à Chartres et en Eure-et-Loir. 1. Je tiens à remercier M. Laurent Bastard, conservateur du musée du Compagnonnage de Tours, pour ses observations et pour son aide documentaire. 2. Pour en savoir plus sur le phénomène des grèves dans le milieu ouvrier, Xavier Vigna : « Pourquoi les ouvriers se révoltent », in l’Histoire, n° 404, octobre 2014, p. -

Métiers, Compagnons, Compagnonnage Et Chef D'œuvre.Pdf

Seconde BAC PRO HISTOIRE Cours adaptable à distance proposé par M.BELLARD Métiers, Compagnons, compagnonnage et chef d’œuvre au XIX e siècle. (en 2 parties) Partie 1 INTRODUCTION (nous allons rendre concret ce qui est abstrait pour la quasi-totalité de nos élèves) Tout d’abord nous demandons aux élèves de visualiser cet extrait : https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x76085g (clic droit pour copier puis coller sur le cahier de texte) Commentaire : La cathédrale de Paris a en partie brulée en 2019.L’état veut faire appel à l’expertise des compagnons pour la reconstruire. Qui sont-ils ? Côté techniQue : Le lien vidéo peut être déposé sur PRONOTE ou l’ENT, les réponses attendues par mail, devoir rendu, ou logiciel exerciseur type QUIZINIERE, tutoriel disponible sur le site) La trace écrite pourra être donné en .PDF en fin de séance ou au fur et à mesure. On peut questionner les élèves sur 2 idées qui apparaissent dans cet extrait : On parle ici de COMPAGNONS, qui sont-ils ? (Des jeunes en formations) comme eux Que font-ils ? (Des métiers manuels Qui nécessitent de l’expertise) Au début de quoi parle-t-on ? D’un tour d’Europe pour se former. Nous y reviendrons. Trace écrite possible : Ainsi il existe de nos jours des corps de métier Qui ont un rôle important dans certaines « communautés de métier ». Ces « compagnons » dans le cadre d’une formation dense et d’un « tour » de France ou d’Europe acQuièrent de nouveaux savoir. Nous chercherons à comprendre comment ce système du compagnonnage toujours présent de nos jours s’est organisé au XIXe siècle ? Commentaire : ce sujet est pour eux, le plus compliqué de l’année, ils ont peu de références, nous chercherons à le rendre concret et lisible. -

Letter to Our Shareholders April 2004

Lettre-avril-2004-GB.qxd 27/05/04 17:47 Page 1 Letter to our Shareholders April 2004 SUMMARY ● Highlights 2003 Annual Results (p.2) ● Hachette Filipacchi Médias A Royal Audience; The Analyst’s Couch…; Elle à Table (p.3) ● Hachette Livre The Annual Book Fair; Bleue Series Celebrates 10 Years of Publishing; Launches (p.4) ● Hachette Distribution Services Launch of Virgin L’hebdo; 33rd Virgin Megastore (p.5) ● Lagardere Active MCM to the Third Power; An Audience for Mezzo; In Brief (p.5) ● Group Going for Gold; the Jean-Luc Lagardère Foundation (p.6) ● EADS 2003 Annual Results; Earth and Sky (p.7) ● Shareholder’s Notebook (p.8) “Where there's a will, we pave the way” EDITORIAL Continued refocusing in the field of the media Since the beginning of 2004, business has been rather and improvements in the profitability of Lagardère Media uneventful, with the exception of significant growth in advertising revenue from radio and theme channels. As promised, we are taking the opportunity of this new Letter Generally speaking, visibility remains mediocre, preventing to provide you with an update on the progress of the Editis the anticipation of different trends over the coming months, (formerly Vivendi Universal Publishing) acquisition. due to the prevailing uncertainties about when and how an economic recovery will take place. An important milestone was passed in January when the For this reason, the forecast growth in operating profits for European Commission gave Lagardère the authorization to Lagardère Media in 2004, excluding the effect of the assets retain some of Editis’ prize assets, in terms of both retained from Editis, are based on two different scenarios: profitability and development potential: Larousse, Dalloz, Dunod and Armand Colin in France, and Anaya in Spain.