Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

Michael Krasny Has Interviewed a Wide Range of Major Political and Cultural Figures Including Edward Albee, Madeleine Albright

Michael Krasny has interviewed a wide range of major political and cultural figures including Edward Albee, Madeleine Albright, Sherman Alexei, Robert Altman, Maya Angelou, Margaret Atwood, Ken Auletta, Paul Auster, Richard Avedon, Joan Baez, Alec Baldwin, Dave Barry, Harry Belafonte, Annette Bening, Wendell Berry, Claire Bloom, Andy Borowitz, T.S. Boyle, Ray Bradbury, Ben Bradlee, Bill Bradley, Stephen Breyer, Tom Brokaw, David Brooks, Patrick Buchanan, William F. Buckley Jr, Jimmy Carter, James Carville, Michael Chabon, Noam Chomsky, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Cesar Chavez, Bill Cosby, Sandra Cisneros, Billy Collins, Pat Conroy, Francis Ford Coppola, Jacques Cousteau, Michael Crichton, Francis Crick, Mario Cuomo, Tony Curtis, Marc Danner, Ted Danson, Don DeLillo, Gerard Depardieu, Junot Diaz, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joan Didion, Maureen Dowd. Jennifer Egan, Daniel Ellsberg, Rahm Emanuel, Nora Ephron, Susan Faludi, Diane Feinstein, Jane Fonda, Barney Frank, Jonathan Franzen, Lady Antonia Fraser, Thomas Friedman, Carlos Fuentes, John Kenneth Galbraith, Andy Garcia, Jerry Garcia, Robert Gates, Newt Gingrich, Allen Ginsberg, Malcolm Gladwell, Danny Glover, Jane Goodall, Stephen Greenblatt, Matt Groening, Sammy Hagar, Woody Harrelson, Robert Hass, Werner Herzog, Christopher Hitchens, Nick Hornby, Khaled Hosseini, Patricia Ireland, Kazuo Ishiguro, Molly Ivins, Jesse Jackson, PD James, Bill T. Jones, James Earl Jones, Ashley Judd, Pauline Kael, John Kerry, Tracy Kidder, Barbara Kingsolver, Alonzo King, Galway Kinnell, Ertha Kitt, Paul Krugman, Ray -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Emmy Nominations

2021 Emmy® Awards 73rd Emmy Awards Complete Nominations List Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The New Me • Netflix • Netflix Bob's Burgers • Worms Of In-Rear-Ment • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television / Bento Box Animation Genndy Tartakovsky's Primal • Plague Of Madness • Adult Swim • Cartoon Network Studios The Simpsons • The Dad-Feelings Limited • FOX • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation South Park: The Pandemic Special • Comedy Central • Central Productions, LLC Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Love, Death + Robots • Ice • Netflix • Blur Studio for Netflix Maggie Simpson In: The Force Awakens From Its Nap • Disney+ • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation Once Upon A Snowman • Disney+ • Walt Disney Animation Studios Robot Chicken • Endgame • Adult Swim • A Stoopid Buddy Stoodios production with Williams Street and Sony Pictures Television Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Contemporary Program (One Hour Or More) The Flight Attendant • After Dark • HBO Max • HBO Max in association with Berlanti Productions, Yes, Norman Productions, and Warner Bros. Television Sara K. White, Production Designer Christine Foley, Art Director Jessica Petruccelli, Set Decorator The Handmaid's Tale • Chicago • Hulu • Hulu, MGM, Daniel Wilson Productions, The Littlefield Company, White Oak Pictures Elisabeth Williams, Production Designer Martha Sparrow, Art Director Larry Spittle, Art Director Rob Hepburn, Set Decorator Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, TPhaeg eL o1w Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, The Low Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem and Zobot Projects Keith P. Cunningham, Production Designer James F. Truesdale, Art Director Edward McLoughlin, Set Decorator The Undoing • HBO • HBO in association with Made Up Stories, Blossom Films, David E. -

Arts and Sciences and Officers

Ac:acre"nv 01 Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and Officers 1980-1981 President Fay Kamn First Vice President Marvin E. Mirisch Vice President Charles M. Powell Vice President Arthur Hamilton Treasurer Gene Allen Secretary Donald C. Rogers Executive Director James M. Roberts Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 8949 Wilshire Boulevard Beverly Hills, California 90211 (213) 278-8990 On cover A singing telegram by the dance troupe outlined the rules by which Academy Awards are given The Academy's headquarters in Beverly Hills was the site of its many screenings, salutes and tribute programs. Eighth Annual Student Film Award winners ,posed with special guests and Academy officials prior to the presentation ceremony. Oscar's domain continued to expand as the Academy increased its special programming in 1980-81 to include new seminars, lectures and an extraordinarily wide variety of film presentations. Background-a print of "Wings;' first picture to win an Academy Award for Best Picture, was presented to the Academy this year by Paramount Pictures. The cover theme is carried through this report, using photos from the Margaret Herrick Library's collection of four-million stills, to chronicle the growth of the film industry. Report from the President am pleased to present to you the traditionally send us foreign language film fourth annual report of the Academy entries. This year I was able to extend the of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Academy's greetings to filmmakers and and the Academy Foundation . The film-lovers abroad as the guest of France events of the past year documented and Greece and to represent the U.S., Ihere reflect the Academy's continuing as well as the Academy, in heading a efforts to fulfill one of the promises of its delegation accompanying the first five charter - to foster educational activities American films sent in a generation to the between the professional community People's Republic of China. -

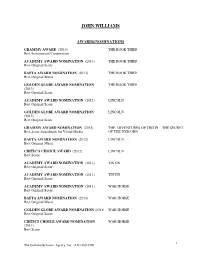

John Williams

JOHN WILLIAMS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS GRAMMY AWARD (201 4) THE BOOK THIEF Best Instrumental Composition ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2013) THE BOOK THIEF Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2013) THE BOOK THIEF Best Original Music GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION THE BOOK THIEF (2013) Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATI ON (2012 ) LINCOLN Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION LINCOLN (2012) Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2012) THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN – THE SECRET Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media OF THE UNICORN BAFTA AWARD NOMINATIO N (2012 ) LINCOLN Best Original Music CRITIC’S CHOICE AWARD (2012) LINCOLN Best Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Ori ginal Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Original Music GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Original Score CRITICS CHOICE AWARD NOMINATION WAR HORSE (2011) Best Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 JOHN WILLIAMS ANNIE AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Music in a Feature Production EMMY AWARD (2009) GREAT PERFORMANCES Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GRAMMY AWARD (2008) “The Adventures of Mutt” Best Instrumental Composition from INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL GRAMMY AWARD (2006) “A Prayer for Peace” Best Instrumental Composition from MUNICH GRAMMY AWARD (2006) MEMOIRS OF A GEISHA Best Score Soundtrack Album GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2006) -

01-Newsletter-060709.Pdf

END OF THE WORLD New SL E TT E R July-August 2009 Issue: 03 Editor Dougie Milton Chief Editors Alan Roughley Nuria Belastegui New S FROM TH E HOUS E Dear Honorary Patrons, Trustees, members and anybody with an interest in Burgess visiting this website: This edition of The End of the World Newsletter has been very of Gerry Docherty and the financial acumen of Gaëtan capably put together and edited by that well-known Burgessian, de Chezelles, purchased new premises to house its Burgess Dougie Milton. Sadly, this will be the first edition of the collection. The Engine House of a renovated cotton mill in Newsletter that Liana Burgess will not be reading. Liana passed central Manchester will provide away in December 2007. Mrs Burgess has provided funding space for readings and performances for us to continue the development of the Foundation until we of Burgess’s literary works and become financially self-sufficient. music, as well as offering an excellent performance space If you know of for writers and musicians from anybody who may Manchester and from the wider want to become national and international contexts. a member of the The Engine House at Chorlton Mill, Foundation, please The renovation of the Engine Manchester pass on our details House at Chorlton Mill is being to them. led by architect Aoife Donnelly. Completion date for the refurbishment of the premises will be late 2009 or very early Since the last 2010. We hope that you will all pencil those dates in your diaries, edition of the and come and help us celebrate the opening of the new IABF. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

American Heritage Center

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER GUIDE TO ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY RESOURCES Child actress Mary Jane Irving with Bessie Barriscale and Ben Alexander in the 1918 silent film Heart of Rachel. Mary Jane Irving papers, American Heritage Center. Compiled by D. Claudia Thompson and Shaun A. Hayes 2009 PREFACE When the University of Wyoming began collecting the papers of national entertainment figures in the 1970s, it was one of only a handful of repositories actively engaged in the field. Business and industry, science, family history, even print literature were all recognized as legitimate fields of study while prejudice remained against mere entertainment as a source of scholarship. There are two arguments to be made against this narrow vision. In the first place, entertainment is very much an industry. It employs thousands. It requires vast capital expenditure, and it lives or dies on profit. In the second place, popular culture is more universal than any other field. Each individual’s experience is unique, but one common thread running throughout humanity is the desire to be taken out of ourselves, to share with our neighbors some story of humor or adventure. This is the basis for entertainment. The Entertainment Industry collections at the American Heritage Center focus on the twentieth century. During the twentieth century, entertainment in the United States changed radically due to advances in communications technology. The development of radio made it possible for the first time for people on both coasts to listen to a performance simultaneously. The delivery of entertainment thus became immensely cheaper and, at the same time, the fame of individual performers grew. -

Putney Swope

THE FILM FOUNDATION 2019 ANNUAL REPORT OVERVIEW The Film Foundation supports the restoration of films from every genre, era, and region, and shares these treasures with audiences through hundreds of screenings every year at festivals, archives, repertory theatres, and other venues around the world. The foundation educates young people with The Story of Movies, its groundbreaking interdisciplinary curriculum that has taught visual literacy to over 10 million US students. In 2019, The Film Foundation welcomed Kathryn Bigelow, Sofia Coppola, Guillermo del Toro, Joanna Hogg, Barry Jenkins, Spike Lee, and Lynne Ramsay to its board of directors. Each has a deep understanding and knowledge of cinema and its history, and is a fierce advocate for its preservation and protection. Preservation and Restoration World Cinema Project Working in partnership with archives and studios, The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project has The Film Foundation has helped save over 850 films restored 40 films from24 countries to date. to date. Completed projects in 2019 included: Completed projects in 2019 included: THE CLOUD– William Wyler’s beloved classic, DODSWORTH; CAPPED STAR (India, 1960, d. Ritwik Ghatak), EL Herbert Kline’s acclaimed documentary about FANTASMA DEL CONVENTO (Mexico, 1934, d. Czechoslovakia during the Nazi occupation, CRISIS: Fernando de Fuentes), LOS OLVIDADOS (Mexico, A FILM OF “THE NAZI WAY”; Arthur Ripley’s film 1950, d. Luis Buñuel), LA FEMME AU COUTEAU noir about a pianist suffering from amnesia, VOICE (Côte d’Ivoire, 1969, d. Timité Bassori), and MUNA IN THE WIND; and John Huston’s 3–strip Technicolor MOTO (Cameroon, 1975, d. Jean–Pierre Dikongué– biography of Toulouse–Lautrec, MOULIN ROUGE. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Sat, Jul 9, 7:00; Wed, Jul 13, 7:00 to Pilfer the Family's Ersatz Van American Film Institute

ISSUE 77 AFI.com/Silver AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER JULY 8–SEPTEMBER 14, 2016 44T H AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREE A FILM RESTROSPECTIVE THE COMPOSER B EHIND THE GREAT EST A MERICAN M OVIES O F OUR TIME PLUS GLORIOUS TECHNICOLOR ★ ’90S C INEMA N OW ★ JOHN C ARPENT E R LOONEY TUNES ★ KEN ADAM REMEMBERED ★ OLIVIA DE HAVILLAND CENTENNIAL Contents AFI Life Achievement Award: John Williams AFI Life Achievement Award: July 8–September 11 John Williams ......................................2 John Williams' storied career as the composer behind many of the greatest American films and television Keepin' It Real: '90s Cinema Now ................6 series of all time boasts hundreds of credits across seven decades. His early work in Hollywood included working as an orchestrator and studio pianist under such movie composer maestros as Bernard Herrmann, Ken Adam Remembered ..........................9 Alfred Newman, Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein and Franz Waxman. He went on to write music for Wim Wenders: Portraits Along the Road ....9 more than 200 television programs, including the groundbreaking anthology series ALCOA THEATRE Glorious Technicolor .............................10 and KRAFT TELEVISION THEATRE. Perhaps best known for his enduring collaboration with director Steven Spielberg, his scores are among the most iconic and recognizable in film history, from the edge-of-your- Special Engagements .................. 14, 16 seat JAWS (1975) motif to the emotional swell of E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL (1982) and the haunting UCLA Festival of Preservation ...............14 elegies of SCHINDLER'S LIST (1993). Always epic in scale, his music has helped define over half a century of the motion picture medium. -

Anthony Burgess and God, Faith and Evil, Language and the Ludic in The

It ! AR'DIOllY BORGBSS Al1D GOD: PAI.'l'H ARD BVIL, LAlGDAGB .Am> 'l'BB UJDIC IB 'l'BB ROVBLS OP A lmlnCDDB 1fORDBOY BY DARRYL ARTBORY 'l'ORClllA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTBR OP ARTS Department of Re1.igion University of llani.toba Winni.peg, llani.toba (C) May, 1997 National Library Bibliotheque nationale l+I of Canada duC8nada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellingtan S1Net 395.. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ollawa ON K1A ON4 C8nada c.nllda The author bas granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnbute or sell reproduire, prater, distnbuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d' auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son penmss1on. autorisation. 0-612-23530-0 Canadrt THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE AllrllORY BDGBSS MD GOD: PAITH A1ID EVIL, LAllGIJAGB AllD 1'llE LUDIC BY NRRYJ.