Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Didache of the Apostles1

The Didache of the Apostles1 The teaching2 of the Lord to the Gentiles through3 the twelve apostles The Two Ways and the First Commandment 1.1 There are two ways, one of life and one of death, and there is much difference between the two ways. 2. On the one hand,4 the way of life is this: first, you shall love5 the God who made you; second, [you shall love] your neighbor as yourself6; but all things, if you want them not to happen to you, then see you do not do to another.7 3. Now the teaching of these words is this: Bless those who curse you,8 and pray for your enemies, but fast for those who persecute you9; for what credit is it if you should love those who love you?10 Don’t even the Gentiles do the same?11 But you must love those who hate you and you will not have an enemy.12 4. Abstain from fleshly and bodily cravings. If someone should give you a slap on the right cheek, turn to him the other also,13 and you will be mature14; If someone compels you to go with him one mile, go with him two15; if someone takes away your cloak, give him your tunic also16; if 1 Based on the translation by J. B. Lightfoot, 1891; but a translation of the recent Greek text: The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations (ed. and transl. Michael W. Holmes; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 20073). Other works consulted: Rodney A. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

Text of the Gospel of Mark: Lake Revisited

BABELAO 3 (2014), p. 145-169 + Appendix, p. 171-289 © ABELAO (Belgium) The « Caesarean » Text of the Gospel of Mark: Lake Revisited By Didier Lafleur IRHT - Paris n the field of history and practice of New Testament textual criticism, two major stages were initiated during the last cen- tury by Kirsopp Lake. The first of these was the publication, Iin 19 02, of a survey concerning Codex 1 of the Gospels and its Allies, in the Texts and Studies series (7:3). The second stage was the pub- lication, in 1928, with Robert P. Blake and Silva New, of « The Caesarean Text of the Gospel of Mark » in the Harvard Theological Review (21:4). For the first time, the authors emphasized the exist- ence of such text on the basis of three major pieces of evidence: the Greek manuscripts, the patristic witnesses and the Oriental versions. Since then, the question of the « Caesarean » text-type has been a very disputed matter. It still remains an important tex- tual issue.1 1 This paper was first presented during the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting 2012, Chicago, November 18. 146 D. LAFLEUR Our plan is not to discuss here about the « Caesarean » text and its subsequent developments, but to mainly focus the genesis of Lake’s publication. The survey of his preliminary works will help us to better consider, after a short account of Lake’s biobibliography, the way he followed until the 1928 « Caesarean Text of the Gospel of Mark » and which methodology he used. We will then emphasize one of the three pieces of evidence quot- ed by the authors, the evidence of the Greek manuscripts as de- scribed in their tables of variants. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

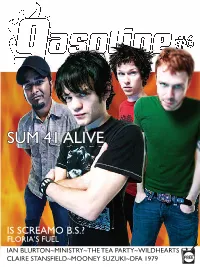

Sum 41 Alive

SSUMUM 4411 AALIVELIVE IS SCREAMO B.S.? FLORIA’S FUEL IAN BLURTON~MINISTRY~THE TEA PARTY~WILDHEARTS CLAIRE STANSFIELD~MOONEY SUZUKI~DFA 1979 THE JERRY CAN The summer is the season of rock. Tours roll across the coun- try like mobile homes in a Florida hurricane. The most memo- rable for this magazine/bar owner were the Warped Tour and Wakestock, where such bands as Bad Religion, Billy Talent, Alexisonfire, Closet Monster, The Trews and Crowned King had audiences in mosh-pit frenzies. At Wakestock, in Wasaga Beach, Ont., Gasoline, Fox Racing, and Bluenotes rocked so hard at their two-day private cottage party that local authorities shut down the stage after Magneta Lane and Flashlight Brown. Poor Moneen didn't get to crush the eardrums of the drunken revellers. That was day one! Day two was an even bigger party with the live music again shut down. The Reason, Moneen and Crowned King owned the patio until Alexisonfire and their crew rolled into party. Gasoline would also like to thank Chuck (see cover story) and other UN officials for making sure that the boys in Sum41 made it back to the Bovine for another cocktail, despite the nearby mortar and gunfire during their Warchild excursion. Nice job. Darryl Fine Editor-in-Chief CONTENTS 6 Lowdown News 8 Ian Blurton and C’mon – by Keith Carman 10 Sum41 – by Karen Bliss 14 Floria Sigismondi – by Nick Krewen 16 Alexisonfire and “screamo” – by Karen Bliss 18 Smash it up – photos by Paula Wilson 20 Whiskey and Rock – by Seth Fenn 22 Claire Stansfield – by Karen Bliss 24 Tea Party – by Mitch Joel -

Legends of the West

1 This novel is dedicated to Vivian Towlerton For the memories of good times past 2 This novel was written mostly during the year 2010 CE whilst drinking the fair-trade coffee provided by the Caffé Vita and Sizizis coffee shops in Olympia, Washington Most of the research was conducted during the year 2010 CE upon the free Wi-Fi provided by the Caffé Vita and Sizizis coffee shops in Olympia, Washington. My thanks to management and staff. It was good. 3 Excerpt from Legends of the West: Spotted Tail said, “Now, let me tell you the worst thing about the Wasicu, and the hardest thing to understand: They do not understand choice...” This caused a murmur of consternation among the Lakota. Choice was choice. What was not there to not understand? Choice is the bedrock tenet of our very view of reality. The choices a person makes are quite literally what makes that person into who they are. Who else can tell you how to be you? One follows one’s own nature and one’s own inner voice; to us this is sacrosanct. You can choose between what makes life beautiful and what makes life ugly; you can choose whether to paint yourself in a certain manner or whether to wear something made of iron — or, as was the case with the famous Cheyenne warrior Roman Nose — you could choose to never so much as touch iron. In battle you choose whether you should charge the enemy first, join the main thrust of attack, or take off on your own and try to steal his horses. -

Harvard Theological Studies I

HARVARD THEOLOGICAL STUDIES I. THE COMPOSITION AND DATE OF ACTS. By Charles Cutler Torrey. 72 pages. 1916. (Out of print.) II. THE PAULINE IDEA OF FAITH IN ITS RELATION TO JEWISH AND HELLENISTIC RELIGION. By W. H. P. Hatch. 92 pages. 1917. (Out of print.) HI. EPHOD AND ARK. By William R. Arnold. 170 pages. 1917. (Out of print.) IV. THE GOSPEL MANUSCRIPTS OF THE GENERAL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. By C. C. Edmunds and W. H. P. Hatch. 68 pages. 1918. $1.25. V. MACARH ANECDOTA. By G. L. Marriott 48 pages. 1918. (Out of print.) VI. THE STYLE AND LITERARY METHOD OF LUKE. By Henry J. Cadbury. 205 pages. 1920. (Out of print.) VH. IS MARK A ROMAN GOSPEL? By B. W. Bacon. 106 pages. 1919. (Out of print.) VIH. THE DEFENSOR PACIS OF MARSIGLIO OF PADUA. By Ephraim Emerton. 81 pages. 1920. (Out of print.) IX. AN ANSWER TO JOHN ROBINSON OF LEYDEN BY A PURITAN FRIEND. Edited by Champlin Burrage. xiv, 94 pages. 1920. $2.00. X. THE RUSSIAN DISSENTERS. By F. C. Conybeare. 1921. (Out of print.) XL CATALOGUE OF THE GREEK MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY OF THE MONASTERY OF VATOPEDI ON MT. ATHOS. By Sophro- nios Eustratiades and Arcadios. iv, 277 pages. 1924. (Out of print.) XU. CATALOGUE OF THE GREEK MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY OF THE LAURA ON MOUNT ATHOS. By Spvridon, of the Laura, and Sophronios Eustratiades. 515 pages. 1925. (Out of print.) XJDU. A KEY TO THE COLLOQUIES OF ERASMUS. By Preserved Smith, vi, 62 pages. 1927. $1.50. XIV. THE SINGULAR PROBLEM OF THE EPISTLE TO THE GALA- TIANS. -

Harvard Theological Review Simon Zelotes

Harvard Theological Review http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR Additional services for Harvard Theological Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Simon Zelotes Kirsopp Lake Harvard Theological Review / Volume 10 / Issue 01 / January 1917, pp 57 - 63 DOI: 10.1017/S0017816000000584, Published online: 03 November 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S0017816000000584 How to cite this article: Kirsopp Lake (1917). Simon Zelotes. Harvard Theological Review, 10, pp 57-63 doi:10.1017/S0017816000000584 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 128.122.253.212 on 05 May 2015 SIMON ZELOTES 57 SIMON ZELOTES KIRSOPP LAKE HARVARD UNIVERSITY Simon Zelotes or Simon the Canamean is one of the Twelve of whom it is customary to say that we know nothing except that his name shows that he had once belonged to the Sect of the Zealots or Cananaeans, the "physical-force men" of the Jews, and that he had after- wards, seeing the error of his ways, adopted the pacific teachings of Jesus. It is therefore somewhat of a shock to discover from Josephus that, if his evidence be correct, the use of the name Zealot to describe a Jewish sect or party cannot be earlier than A.D. 66. For this reason it seems op- portune to bring together the facts dealing with the Zealots and cognate contemporary movements, and in their light to ask once more what is the meaning of "Simon the Zealot." The usual assumptions1 with regard to the Zealots are that they were the followers of Judas the Gaulonite of Gamala, also called Judas of Galilee, who founded in A.D. -

Harvard Theological Review

THE HARVARD THEOLOGICAL REVIEW VOLUME XV ISSUED QUARTERLY BY THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY IN HARVARD UNIVERSITY CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1922 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 02 Oct 2021 at 16:19:02, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S001781600000136X THBOUJGK < •},- *?' THE Harvard Theological Review is maintained by the aid of the bequest of Mildred Everett, daughter of Charles Carroll Everett, D.D., Bussey Professor of Theology in Harvard University, 1869- 1900, and Dean of the Faculty of Divinity, 1878-1900. The Review is edited for the Faculty of Theology by the follow- ing Committee: GEORGE F. MOOBE FREDERICK PALMER WILLIAM B. ARNOLD JAMES H. ROPES KIRSOPP LAKE Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 02 Oct 2021 at 16:19:02, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S001781600000136X CONTENTS OF VOLUME XV NUMBER 1, JANUARY 1922 THE SOCIAL TRANSLATION OF THE GOSPEL . Henry J. Cadbury 1 KING JOHN AND THE NORMAN CHURCH . Sidney R. Packard 15 INTERMEDIARIES IN JEWISH THEOLOGY . George Foot Moore 41 SOME STUDIES ON THE IRANIAN RELIGIONS . Louis H. Gray 87 THE PROBLEM OF CHRISTIAN ORIGINS Kirsojrp Lake 97 NUMBER 2, APRIL 1922 LITERATURE ON THE NEW TESTAMENT IN GERMANY, AUSTRIA, SWITZERLAND, HOLLAND, AND THE SCANDINAVIAN COUNTRIES, 1914-1920 Hans Windisch 115 NUMBER 3, JULY 1922 THE CALL TO THE MINISTRY WUlard L. -

Harvard Theological Review American, English, and Dutch

Harvard Theological Review http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR Additional services for Harvard Theological Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here American, English, and Dutch Theological Education Kirsopp Lake Harvard Theological Review / Volume 10 / Issue 04 / October 1917, pp 336 - 351 DOI: 10.1017/S0017816000000973, Published online: 03 November 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S0017816000000973 How to cite this article: Kirsopp Lake (1917). American, English, and Dutch Theological Education. Harvard Theological Review, 10, pp 336-351 doi:10.1017/ S0017816000000973 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 61.129.42.15 on 06 May 2015 336 HARVARD THEOLOGICAL REVIEW AMERICAN, ENGLISH, AND DUTCH THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION1 KIRSOPP LAKE HAKVAKD UNIVERSITY To the student of differing methods of education the chief interest of a comparison between English, Conti- nental, and American methods is that the first two represent entirely different views as to objects and methods, while American education is a 'compromise between them. It is therefore perhaps desirable before proceeding to discuss theological education in particular to develop a little more fully the general characteristics of the three forms. The most important characteristic of English educa- tion is that in the English university the period of training in general culture, as distinct from professional instruction, is carried on longer, further, and to a more advanced stage than in any other country. The normally well-educated Englishman lives at a boarding-school, commonly known as a public school, from thirteen to between eighteen and nineteen. -

Words, Lines, Diagrams, Images: Towards a History of Scientific

Early Science and Medicine 14 (2009) 398-439 www.brill.nl/esm Words, Lines, Diagrams, Images: Towards a History of Scientific Imagery Christoph Lüthy & Alexis Smets* Radboud University Nijmegen To John E. Murdoch, eminent iconographer Abstract is essay examines the problems encountered in contemporary attempts to establish a typology of medieval and early modern scientific images, and to associate apparent types with certain standard meanings. Five particular issues are addressed here: (i) the unclear boundary between words and images; (ii) the problem of morphologically similar images possessing incompatible meanings; (iii) the converse problem of com- parable objects or processes being expressed by extremely dissimilar visual means; (iv) the impossibility of matching modern with historical iconographical terminologies; and (v) the fact that the meaning of a given image can only be grasped in the context of the epistemological, metaphysical and social assumptions within which it is embed- ded. e essay ends by concluding that no scientific image can ever be understood apart from its philosophical preconditions, and that these preconditions are often explained during disputes between the protagonists of different iconographical types. Keywords scientific imagery, epistemic images, word and image, taxonomy of images, iconogra- phy, chymistry, Marsilio Ficino, Giordano Bruno, René Descartes * Faculty of Philosophy, Radboud University Nijmegen, P.O. Box 9103, NL—6500 HD Nijmegen, e Netherlands ([email protected]; [email protected]). We would like to thank the editors of this volume, William R. Newman and Edith Sylla, for their precious comments and observations. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI : 10.1163/157338209X425632 C. Lüthy, A. -

Prelims Bibliography--New Testament Area 1

Prelims Bibliography--New Testament Area 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATIONS NEW TESTAMENT AREA GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY General: Aune, David E. The New Testament in Its Literary Environment. Library of Early Christianity. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1987. Bauer, Walter. Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. 1934. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971. Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. Hays, Richard B. The Moral Vision of the New Testament: Community, Cross, New Creation. A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1997. Hurtado, Larry W. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Grand Rapids/Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2003. Kümmel, Werner Georg. The New Testament: The History of the Investigation of Its Problems. Nashville/New York: Abingdon Press, 1972. Moore, S. D. Literary Criticism and the Gospels: The Theoretical Challenge. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. Robinson, James M., and Helmut Koester. Trajectories Through Early Christianity. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971. Rowland, Christopher. Christian Origins: An Account of the Setting and Character of the Most Important Messianic Sect of Judaism. 2nd ed. London: SPCK, 2002. Schussler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad, 1983. Smith, Jonathan Z. Drudgery Divine: On the Comparison of Early Christianities and the Religions of Late Antiquity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. Historical Jesus: Allison, Dale C. “Jesus and the Victory of Apocalyptic.” Pp. 126-41 in Jesus and the Restoration of Israel: A Critical Assessment of N. T. Wright’s Jesus and the Victory of God.