Decentralized Provision of Public Services and Governance and Management of Renewable Natural Resources: the Senegal Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acte III Une Réforme, Des Questions Une Réforme, Des Questions

N°18 - Août 2015 MAURITANIE PODOR DAGANA Gamadji Sarré Dodel Rosso Sénégal Ndiandane Richard Toll Thillé Boubakar Guédé Ndioum Village Ronkh Gaé Aéré Lao Cas Cas Ross Béthio Mbane Fanaye Ndiayène Mboumba Pendao Golléré SAINT-LOUIS Région de Madina Saldé Ndiatbé SAINT-LOUIS Pété Galoya Syer Thilogne Gandon Mpal Keur Momar Sar Région de Toucouleur MAURITANIE Tessekéré Forage SAINT-LOUIS Rao Agnam Civol Dabia Bokidiawé Sakal Région de Océan LOUGA Léona Nguène Sar Nguer Malal Gandé Mboula Labgar Oréfondé Nabbadji Civol Atlantique Niomré Région de Mbeuleukhé MATAM Pété Ouarack MATAM Kelle Yang-Yang Dodji Gueye Thieppe Bandègne KANEL LOUGA Lougré Thiolly Coki Ogo Ouolof Mbédiène Kamb Géoul Thiamène Diokoul Diawrigne Ndiagne Kanène Cayor Boulal Thiolom KEBEMER Ndiob Thiamène Djolof Ouakhokh Région de Fall Sinthiou Loro Touba Sam LOUGA Bamambé Ndande Sagata Ménina Yabal Dahra Ngandiouf Geth BarkedjiRégion de RANEROU Ndoyenne Orkadiéré Waoundé Sagatta Dioloff Mboro Darou Mbayène Darou LOUGA Khoudoss Semme Méouane Médina Pékesse Mamane Thiargny Dakhar MbadianeActe III Moudéry Taïba Pire Niakhène Thimakha Ndiaye Gourèye Koul Darou Mousty Déali Notto Gouye DiawaraBokiladji Diama Pambal TIVAOUANE de la DécentralisationRégion de Kayar Diender Mont Rolland Chérif Lô MATAM Guedj Vélingara Oudalaye Wourou Sidy Aouré Touba Région de Thiel Fandène Thiénaba Toul Région de Pout Région de DIOURBEL Région de Gassane khombole Région de Région de DAKAR DIOURBEL Keur Ngoundiane DIOURBEL LOUGA MATAM Gabou Moussa Notto Ndiayène THIES Sirah Région de Ballou Ndiass -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

SEN FRA REP2 1999.Pdf

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE Projet GCP/SEN/048/NET Recensement National de l’Agriculture et Système Permanent de Statistiques Agricoles RECENSEMENT NATIONAL DE L’AGRICULTURE 1998-99 Volume 2 Répertoire des villages d’après le pré-recensement de l’agriculture 1997-98 Août 1999 ___________________________________________________________________________ ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ALIMENTATION ET L’AGRICULTURE (FAO) Sommaire Données récapitulatives par unité administrative ……………………………………….… 9 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Dakar …………………………………….. 35 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Diourbel …………………………………. 41 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Saint-Louis ………………………….….. 105 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Tambacounda …………………………... 157 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Kaolack …………………………………. 237 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Thiès ……………………………………. 347 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Louga …………………………………… 427 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Fatick …………………………………… 557 Données individuelles relatives à la région de Kolda …………………………………… 617 Carte administrative du Sénégal ………………………………………………………… 727 3 Avant-propos Ce volume 2 des publications sur le pré-recensement de l’agriculture 1997-98 est consacré à la publication d’un répertoire des villages construit à partir des données issues des opérations de collecte du pré-recensement qui ont consisté en une opération de cartographie censitaire et en une enquête sur les ménages ruraux. Le répertoire des villages publié dans ce volume 2 est simplement la liste exhaustive des villages, avec pour chaque village, les valeurs de plusieurs paramètres de taille. A titre d’exemple, l’effectif des concessions rurales, l’effectif des ménages ruraux et l’effectif des ménages ruraux agricoles sont trois variables de taille du village dont les valeurs figurent dans ce répertoire des villages. -

Economic Growth Project

ECONOMIC GROWTH PROJECT CONTRACT 685-I-00-06-00005-00 TA SK ORDER 5 FY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OCTO BER 1, 2012 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 October 2013 This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of International Resources Group (IRG) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. ECONOMIC GROWTH PROJECT CONTRACT 685-I-00-06-00005-00 TASK ORDER 5 FY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2012 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 October 2013 Submitted by International Resources Group (IRG) DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government Economic Growth Project FY 2013 Annual Report i CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Highlights FY2013 ................................................................................................................................................. 3 FY2013 Feed the Future Indicator Overview .................................................................................................. -

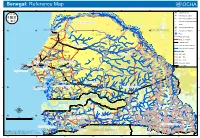

Senegal: Reference Map

Senegal: Reference Map 18°0'0"W 17°0'0"W 16°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 14°0'0"W 13°0'0"W 12°0'0"W !! Podor ! Niandane !^ Capitale d'Etat ! ! Guede Chantiers ! ! Guede Gae Thille-Boubacar ! ! Demet Fanaye ! ! ! Ndiayene ! !Ndioum Oualalde !! ! ! Dodel ! Chef-lieu de région ! Richard-Toll ! Rosso !! Bokhol Gamadji ! Bode Ronkh ! ! Dagana p !! Ndombo Cascas Chef-lieu de département ! !Doumga Madina Ndiatebe ! Ross-Bethio Mbane ! Chef-lieu d'arrondissement ! ! Golere Région de Saint Louis ! Ndiaye ! Meri ! ! ! ! ! Autre !Gnith Salde Diama o ! Mbouba ! !Pete Syer Aéroport international ! ! Galoya Toucouleur Bokke Dialloube ! ! ! Mbolo Birane Agnam Goli Saint-Louis !! ! 16°0'0"N p ! p 16°0'0"N !Gandon Bogal Aéroport secondaire ! Thilogne Nguiguilone Fas Ngom Keur Momar Sarr ! MAURITANIE ! Dabia Mpal ! ! ! ! ! Rao ! Tessekre Forage Boki Diave 0 Port Ndiebene Gandiol ! Lagbar (! ! ! Sakal !Nabadji Route principale Ngueune !Nguermalal ! Sar ! Leona ! ! Mbeuleukhe Niomre ! Pete Ouarak ! !! Route secondaire Mboula Louguere Thioly ! Matam !! ! ! Louga Ourossogui ! Gande ! ! Yang Yang Odobere Ogo ! ! Tiep Kel Gueye Kamb Dodji p ! Chemin de fer ! Coki ! p ! ! ! ! ! ! Gueoul ! !Thiamene ! Mbediene Kanel ! Région de Louga Cours d'eau permanent Ndiagne !Ouro Sidi Kebemer Ngourane Guet Ardo! Boulal Ouarkhokh Linguere ! ! !! ! ! ! ! Tiolom Fall ! Dahra ! Amady Ounare Diokoul Diavrigne ! Sinntiou Bamambe ! ! Kanene Ndiob ! Cours d'eau temporaire Kab Gaye Thiamene ! Ranerou Dendory ! Loro ! !! ! ! ! !Ngandiouf ! ! !Touba Merina Orkadiere Ndande Sagatta ! Sagata Waounde -

Mapping and Remote Sensing of the Resources of the Republic of Senegal

MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL SDSU-RSI-86-O 1 -Al DIRECTION DE __ Agency for International REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE L'AMENAGEMENT Development DU TERRITOIRE ..i..... MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL For THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL LE MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUP SECRETARIAT D'ETAT A LA DECENTRALISATION Prepared by THE REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY BROOKINGS, SOUTH DAKOTA 57007, USA Project Director - Victor I. Myers Chief of Party - Andrew S. Stancioff Authors Geology and Hydrology - Andrew Stancioff Soils/Land Capability - Marc Staljanssens Vegetation/Land Use - Gray Tappan Under Contract To THE UNITED STATED AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING PROJECT CONTRACT N0 -AID/afr-685-0233-C-00-2013-00 Cover Photographs Top Left: A pasture among baobabs on the Bargny Plateau. Top Right: Rice fields and swamp priairesof Basse Casamance. Bottom Left: A portion of a Landsat image of Basse Casamance taken on February 21, 1973 (dry season). Bottom Right: A low altitude, oblique aerial photograph of a series of niayes northeast of Fas Boye. Altitude: 700 m; Date: April 27, 1984. PREFACE Science's only hope of escaping a Tower of Babel calamity is the preparationfrom time to time of works which sumarize and which popularize the endless series of disconnected technical contributions. Carl L. Hubbs 1935 This report contains the results of a 1982-1985 survey of the resources of Senegal for the National Plan for Land Use and Development. -

GIS and Remote Sensing for Environment Statistics

The use of GIS and remote sensing for environment statistics Jacques-André NDIONE1, Mamadou FAYE2 1- Centre de Suivi Ecologique (CSE), BP 15532, Fann Residence, Dakar, SENEGAL [email protected] 2- Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD), (ANSD), Dakar, Sénégal, [email protected], [email protected] Outline • Introduction • Concepts – Environment statistics – Remote sensing – GIS • Examples of using RS and GIS • Conclusion Climate change should be added… Ongoing dialogue between data demand and data supply… Environment statistics “Environment statistics are statistics that describe the state and trends of the environment, covering the media of the natural environment (air/climate, water, land/soil), the biota within the media, and human settlements.” UNSD. 1997. Glossary of Environment Statistics, Studies in Methods, Series F, No. 67 Environment statistics (2) Scope of Environment Stats Perception of major users and producers (UNECA) Socioeconomic and Specific to Ezigbalike environmental particular policies conditions Dozie : Courtesy Environment statistics (3) FDES The challenge of producing environment statistics (UNECA) Ezigbalike Dozie : Courtesy Remote sensing: definition • Remote sensing is the collection of information about an object without being in direct physical contact with the object. • Remote Sensing is a technology for sampling electromagnetic radiation to acquire and interpret non-immediate geospatial data from which to extract information about features, objects, and classes on the Earth's land surface, oceans, and atmosphere. (UNECA) - Dr. Nicholas Short Ezigbalike Dozie : 9 Courtesy Elements involved in Remote sensing 1. Energy Source or Illumination (A) 2. Radiation and the Atmosphere (B) 3. Interaction with the Object (C) 4. Recording of Energy by the Sensor (D) 5. -

Les Territoires D'élevage Laitier À L'épreuve Des Dynamiques Politiques

UNIVERSITÉ CHEIKH ANTA DIOP DE DAKAR Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines Département de Géographie Thèse de Doctorat de Troisième Cycle Les territoires d’élevage laitier à l’épreuve des dynamiques politiques et économiques : Éléments pour une géographie du lait au Sénégal Présentée par : DJIBY DIA Directeur de recherche : Encadrement : CHEIKH BA ALIOUNE BA PROFESSEUR MAÎTRE-ASSISTANT FLSH/UCAD FLSH/UCAD Thèse soutenue publiquement le 13 juin 2009 Jury : Cheikh BA, Professeur à l’UCAD Alioune BA, Maître-assistant à l’UCAD Paul NDIAYE, Maître-assistant à l’UCAD Guillaume DUTEURTRE, Chercheur à l’ISRA-BAME Année universitaire 2008-2009 Les territoires d’élevage laitier à l’épreuve des dynamiques politiques et économiques : Éléments pour une géographie du lait au Sénégal Sommaire RÉSUMÉ p. 4 ABSTRACT p. 5 AVANT-PROPOS p. 6 LISTE DES SIGLES ET ACRONYMES p. 9 INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE L’espace pastoral face à la mondialisation p. 15 PREMIÈRE PARTIE p. 22 Contexte historique de la filière laitière au Sénégal CHAPITRE PREMIER p. 24 Éléments conceptuels pour l’analyse des relations filières-territoires dans le secteur laitier au Sénégal CHAPITRE II p. 45 L’évolution historique de l’élevage au Sénégal : une « hybridation » politique CHAPITRE III p. 75 Les acteurs et leur espace CONCLUSION PARTIELLE p. 106 DEUXIÈME PARTIE p. 107 Le lait dans des ensembles géographiques connexes : la zone sylvopastorale, le bassin arachidier et le littoral CHAPITRE IV p. 109 L’élevage laitier en zone sylvopastorale, transition entre la vallée du fleuve Sénégal et le bassin arachidier CHAPITRE V p. 142 Des outils modernistes dans un système traditionnaliste : l’expérience des usines kosam de Nestlé en zone sylvopastorale CHAPITRE VI p. -

DECRET N° 2002-166 DU 21 FEVRIER 2002 Fixant Le Ressort

DECRET N° 2002-166 DU 21 FEVRIER 2002 fixant le ressort territorial et le chef-lieu des régions et des départements, modifié par les décrets n° 2005-339 du 15 avril 2005. (J.O. n° 6031, p. 895) LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE Vu la constitution, notamment en ses articles 43 et 76 ; Vu la loi n° 72-02 du 1er février 1972 relative à l’organisation de l’Administration territoriale, modifiée par la loi n° 76-6 1 du 26 juin 1976, la loi n°84-22 du 24 mars 1984, la loi n°96-10 du 22 mars 1996 et la loi n°2002-02 du 15 février 2002 ; Vu le décret n° 84-502 du 17 mai 1984 fixant le ressort territorial et le chef-lieu des régions et des départements; Sur le rapport du Ministre de L’Intérieur ; DECRETE Article premier. (Décret n°2005-339 du 15 avril 2005) Le ressort territorial et le chef-lieu des régions et des départements sont fixés par le tableau suivant : CHEF-LIEU CHEF-LIEU DE COMMUNAUTE REGION DEPARTEMENT COMMUNE ARRONDISSEMENT DE REGION DEPARTEMENT RURALE Almadies Dakar plateau DAKAR DAKAR Dakar Grand Dakar Parcelles Assainies GUEDIAWAYE GUEDIAWAYE Guédiawaye Guédiawaye R R A A K K Dagoudane A A PIKINE PIKINE Pikine Niayes D D Thiaroye Bargny Rufisque Diamniadio RUFISQUE RUFISQUE Rufisque Sangalkam Sangalkam Sébikhotane Yène ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Recueil des textes sur les collectivités locales -

Estimating the Burden of Malaria in Senegal: Bayesian Zero-Inflated Binomial Geostatistical Modeling of the MIS 2008 Data

Estimating the Burden of Malaria in Senegal: Bayesian Zero-Inflated Binomial Geostatistical Modeling of the MIS 2008 Data Federica Giardina1,2, Laura Gosoniu1,2, Lassana Konate3, Mame Birame Diouf4, Robert Perry5, Oumar Gaye6, Ousmane Faye3, Penelope Vounatsou1,2* 1 Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland, 2 University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 3 Faculte´ des Sciences et Techniques, UCAD Dakar, Se´ne´gal, 4 National Malaria Control Programme, Dakar, Se´ne´gal, 5 Center for Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, 6 Faculte´ de Me´decine, Pharmacie et Odontologie, UCAD Dakar, Se´ne´gal Abstract The Research Center for Human Development in Dakar (CRDH) with the technical assistance of ICF Macro and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) conducted in 2008/2009 the Senegal Malaria Indicator Survey (SMIS), the first nationally representative household survey collecting parasitological data and malaria-related indicators. In this paper, we present spatially explicit parasitaemia risk estimates and number of infected children below 5 years. Geostatistical Zero-Inflated Binomial models (ZIB) were developed to take into account the large number of zero-prevalence survey locations (70%) in the data. Bayesian variable selection methods were incorporated within a geostatistical framework in order to choose the best set of environmental and climatic covariates associated with the parasitaemia risk. Model validation confirmed that the ZIB model had a better predictive ability than the standard Binomial analogue. Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods were used for inference. Several insecticide treated nets (ITN) coverage indicators were calculated to assess the effectiveness of interventions. -

Senegal Mapping the Poor in Senegal : Technical Report

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE (A.N.S.D.) SENEGAL MAPPING THE POOR IN SENEGAL : TECHNICAL REPORT 2016 MAPPING THE POOR IN SENEGAL: TECHNICAL REPORT DRAFT VERSION 1. Introduction Senegal has been successful on many fronts such as social stability and democratic development; its record of economic growth and poverty reduction however has been one of mixed results. The recently completed poverty assessment in Senegal (World Bank, 2015b) shows that national poverty rates fell by 6.9 percentage points between 2001/02 and 2005/06, but subsequent progress diminished to a mere 1.6 percentage point decline between 2005/06 and 2011, from 55.2 percent in 2001 to 48.3 percent in 2005/06 to 46.7 percent in 2011. In addition, large regional disparities across the regions within Senegal exist with poverty rates decreasing from North to South (with the notable exception of Dakar). The spatial pattern of poverty in Senegal can be explained by factors such as the lack of market access and connectivity in the more isolated regions to the East and South. Inequality remains at a moderately low level on a national basis but about two-thirds of overall inequality in Senegal is due to within-region inequality and between-region inequality as a share of total inequality has been on the rise during the 2000s. As a Sahelian country, Senegal faces a critical constraint, inadequate and unreliable rainfall, which limits the opportunities in the rural economy where the majority of the population still lives to differing extents across the regions. -

NOTES TECHNIQUES February 2017 TECHNICAL REPORTS No

NOTES TECHNIQUES February 2017 TECHNICAL REPORTS No. 25 Socio-physical Vulnerability to Flooding in Senegal An Exploratory Analysis with New Data & Google Earth Engine Authors Bessie SCHWARZ, Beth TELLMAN, Jonathan SULLIVAN, Catherine KUHN, Richa MAHTTA, Bhartendu PANDEY, Laura HAMMETT (Cloud To Street), Gabriel PESTRE (Data-Pop Alliance) Coordination Thomas ROCA (AFD) Country Senegal Key words Data-science, Flood, Machine Learning, Satellite, Vulnerability AFD, 5 rue Roland Barthes, 75598 Paris cedex 12, France ̶ +33 1 53 44 31 31 ̶ +33 1 53 44 39 57 [email protected] ̶ http://librairie.afd.fr AUTHORS AUTHORS Bessie SCHWARZ, Beth TELLMAN, Jonathan SULLIVAN, Catherine KUHN, Richa MAHTTA, Bhartendu PANDEY, Laura HAMMETT (Cloud to Street), Gabriel PESTRE (Data-Pop Alliance) ORIGINAL LANGUAGE English ISSN 2492-2838 COPYRIGHT 1st quarter 2017 DISCLAIMER The analyses and conclusions in this document in no way reflect the views of the Agence Française de Développement or its supervisory bodies. All Technical Reports can be downloaded on AFD’s publications website: http://librairie.afd.fr 1 | TECHNICAL REPORT – N°24 – FEBRUARY 2017 Contents Contents AUTHORS ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 CONTENTS .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................................................