Fishguard (Invasion) Research (Border Archaeology, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solva Proposals Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 1

Solva_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 1 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority Solva Conservation Area Proposals Supplementary Planning Guidance to the Local Development Plan for the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Adopted 12 October 2011 Solva_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 1 SOLVA CONSERVATION AREA PROPOSALS CONTENTS PAGE NO. FOREWORD . 3 1. Introduction. 5 2. Character Statement Synopsis . 7 3. SWOT Analysis. 14 4. POST Analysis . 18 5. Resources . 21 6. Public Realm . 23 7. Traffic Management. 25 8. Community Projects. 26 9. Awareness . 27 10. Development . 29 11. Control . 30 12. Study & Research. 31 13. Boundaries . 32 14. Next Steps . 34 15. Programme . 35 16. Abbreviations Used . 36 Appendix A: Key to Conservation Area Features Map October 2011 Solva_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 2 PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK Poppit A 487 Aberteifi Bae Ceredigion Llandudoch Cardigan Cardigan Bay St. Dogmaels AFON TEIFI A 484 Trewyddel Moylegrove Cilgerran A 487 Nanhyfer Nevern Dinas Wdig Eglwyswrw Boncath Pwll Deri Goodwick Trefdraeth Felindre B 4332 Newport Abergwaun Farchog Fishguard Aber-mawr Cwm Gwaun Crosswell Abercastle Llanychaer Gwaun Valley B 4313 Trefin Bryniau Preseli Trevine Mathry Presely Hills Crymych Porthgain A 40 Abereiddy Casmorys Casmael Mynachlog-ddu Castlemorris Croesgoch W Puncheston Llanfyrnach E Treletert S Rosebush A 487 T Letterston E B 4330 R Caerfarchell N C L Maenclochog E Tyddewi D Cas-blaidd Hayscastle DAU Wolfscastle B 4329 B 4313 St Davids Solfach Cross Solva Ambleston Llys-y-fran A 487 Country Park Efailwen Spittal EASTERN CLEDDAU Treffgarne Newgale A 478 Scolton Country Park Llandissilio Llanboidy Roch Camrose Ynys Dewi Ramsey Island Clunderwen Solva Simpson Cross Clarbeston Road Nolton Conservation Area Haverfordwest Llawhaden Druidston Hwlffordd A 40 B 4341 Hendy-Gwyn St. -

Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port Environmental Statement Volume II: Figures

Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port Environmental Statement Volume II: Figures rpsgroup.com Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port CONTENTS FIGURES * Denotes Figures embodied within text of relevant ES chapter (Volume I) Figure 2.1: Site Location M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-9000 Figure 2.2: Single Tier Linkspan Layout Plan M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-1004 *Figure 2.3: Open Piled Deck, Bankseat and Linkspan Ramp *Figure 2.4: Bankseat *Figure 2.5: Landside of Buffer Dolphin and Linkspan Ramp *Figure 2.6: Seaward Edge of Buffer Dolphin Showing Forward End of Linkspan Ramp *Figure 2.7: Jack Up Pontoon Figure 2.8: Demolition and site clearance M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-9002 Figure 2.9: Linkspan levels M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-3001 *Figure 2.10: Typical Backseat Plan and Section, showing pile arrangement *Figure 2.11: Indicative Double Tiered Linkspan Layout Figure 2.12: Proposed site compound locations M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-9003 *Figure 3.1: Comparison of Alternative Revetment Designs *Figure 4.1: Extent of hydraulic model of Fishguard harbour and its approaches *Figure 4.2: Wave disturbance patterns – 1 in 50 year return period storm from N *Figure 4.3: Significant wave heights and mean wave direction 1 in 50 year return period storm from 120° N *Figure 4.4: Typical tidal flood flow patterns in Fishguard Harbour *Figure 4.5: Typical tidal ebb flow patterns in Fishguard Harbour *Figure 4.6: Tidal levels currents and directions at the linkspan site – spring tide *Figure 4.7: Tidal current speed difference, proposed minus existing, at time of maximum current speed at -

Welsh Route Study March 2016 Contents March 2016 Network Rail – Welsh Route Study 02

Long Term Planning Process Welsh Route Study March 2016 Contents March 2016 Network Rail – Welsh Route Study 02 Foreword 03 Executive summary 04 Chapter 1 – Strategic Planning Process 06 Chapter 2 – The starting point for the Welsh Route Study 10 Chapter 3 - Consultation responses 17 Chapter 4 – Future demand for rail services - capacity and connectivity 22 Chapter 5 – Conditional Outputs - future capacity and connectivity 29 Chapter 6 – Choices for funders to 2024 49 Chapter 7 – Longer term strategy to 2043 69 Appendix A – Appraisal Results 109 Appendix B – Mapping of choices for funders to Conditional Outputs 124 Appendix C – Stakeholder aspirations 127 Appendix D – Rolling Stock characteristics 140 Appendix E – Interoperability requirements 141 Glossary 145 Foreword March 2016 Network Rail – Welsh Route Study 03 We are delighted to present this Route Study which sets out the The opportunity for the Digital Railway to address capacity strategic vision for the railway in Wales between 2019 and 2043. constraints and to improve customer experience is central to the planning approach we have adopted. It is an evidence based study that considers demand entirely within the Wales Route and also between Wales and other parts of Great This Route Study has been developed collaboratively with the Britain. railway industry, with funders and with stakeholders. We would like to thank all those involved in the exercise, which has been extensive, The railway in Wales has seen a decade of unprecedented growth, and which reflects the high level of interest in the railway in Wales. with almost 50 per cent more passenger journeys made to, from We are also grateful to the people and the organisations who took and within Wales since 2006, and our forecasts suggest that the time to respond to the Draft for Consultation published in passenger growth levels will continue to be strong during the next March 2015. -

Outer Milford Haven Area Name

Seascape Character Area Description Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Seascape Character Assessment No: 31 Seascape Character Outer Milford Haven Area Name: Panorama looking north over Angle Bay, refinery visible on right Mouth of Milford Sound from near Rat Island, with ferry off St Ann's Head In the mout h of the Sou nd approx 500m from shore 31-1 Supplementary Planning Guidance: Seascape Character Assessment December 2013 Seascape Character Area Description Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Seascape Character Assessment Dale Roads with refinery in distance Sandyhaven Pill (©John Briggs) Summary Description The area forms the outer part of Milford Haven which is a large sheltered drowned ria. The mouth of the Sound has an exposed open sea aspect with strong tides and currents contrasting with the sheltered bay of Dale, small beach at West Angle Bay, and creeks such as Sandyhaven Pill. There is nature conservation interest especially around Dale and coastal forts relating to the Haven’s historic strategic value. The sea area is busy with ferry and commercial shipping, with the refinery and other energy and port infrastructure in background views and the area is popular for recreation and sailing, especially around Dale. aspectKey Characteristics Large sheltered drowned ria with red steep sandstone cliffs and sheltered bays and shallow creeks. Mouth of the Haven has an open sea character with strong currents and swell. Rolling inland landcover comprises open arable and pasture with low hedgebanks, with deciduous woodland in incised valleys. Traditional and medieval settlements. Historical military features and associations including forts. Busy natural harbour mouth with large vessels including tankers and ferries using the waters. -

Fishguard PD

Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port Environmental Statement Non Technical Summary rpsgroup.com Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction This Environmental Statement (ES) is provided in support of a Marine Licence application, submitted to Natural Resources Wales (NRW) by Stena Line, in respect of the proposed replacement of the existing linkspan at Fishguard Port, Pembrokeshire, Wales. This ES should be read in conjunction with the Marine Licence application and all supporting information including the following drawings: • M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-1000 Illustrative Drawing Site Location • M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-1003 Site Boundary • M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-1004 Single Tier Linkspan Layout Plan • M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-2000 Demolition & Site Clearance The proposed development is described in detail in Chapter 2 of this ES. 1.2 Marine Licence Context Under the Marine and Coastal Access Act (MCAA) 2009, it is a licensable marine activity to undertake a range of activities as defined by Section 66 of the Act, including: • Deposition of any substance or object, in the sea or on or under the sea bed, from: − Any vehicle, vessel, aircraft or marine structure − Any container floating in the sea − Any structure on land constructed or adapted wholly or mainly for the purpose of depositing solids in the sea • Construction, alteration or improvement works either in or over the sea or on or under the sea bed • Use of a vehicle, vessel, aircraft, marine structure or floating container to remove any substance or object from the sea bed • Carrying out any form of dredging, whether or not involving the removal of any material from the sea or sea bed The MCAA defines ‘the sea’ as: • Any area submerged at mean high water spring tide. -

The London Gazette Bp Sutfjorttp

Number 51514 12011 The London Gazette bp Sutfjorttp Registered as a Newspaper at the Post Office THURSDAY, 27ra OCTOBER 1988 State Intelligence Cambria House, Haverfordwest, and at the Welsh Office Highways WELSH OFFICE Directorate, Roads Administration Division, Phase 1, Government Buildings, Ty Glas Road, Llanishen, Cardiff, where they are open to Y SWYDDFA GYMREIG inspection, free of charge, at all reasonable hours. HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 Copies of the section 10 Order, the title of which is "The London—Fishguard Trunk Road (Haverfordwest Eastern By-pass) The London—Fishguard Trunk Road (Haverfordwest Eastern By- Order 1988 (S.I. 1988 No. 1664)" can be purchased (price 4Sp) Pass) Order 1988 through booksellers or direct from Government bookshops The London—Fishguard Trunk Road (Haverfordwest Eastern By- (H.M.S.O.). Pass, Side Roads) Order 1988 Copies of the section 14 Order, the title of which is "The The Secretary -of State for Wales hereby gives notice that he has London—Fishguard Trunk Road (Haverfordwest Eastern By-pass, made the following Orders: Side Roads) Order 1988" can be obtained from the Welsh Office, (1) An Order under section 10 of the Highways Act 1980, Highways Directorate, Roads Administration Division, Phase 1, providing: Government Buildings, Ty Glas Road, Llanishen, Cardiff CF4 SPL. Copies of the Order plans can be purchased from the Welsh Office, (a) that a road about 1825 metres in length which he proposes to construct from a point on Narberth Road about 330 metres Highways Directorate, Roads Administration Division, Phase 1, west of the access to Bethany Farm, extending in a north- Government Buildings, Ty Glas Road, Llanishen, Cardiff CF4 SPL. -

Inclusive Design, Access & Sustainability Statement

Inclusive Design, Access & Sustainability Statement Proposed residential development of 17 No. affordable housing units. The application is also to include, infrastructure, partial hedgerow removal, landscaping improvements, biodiversity mitigation & enhancements; and any ancillary works on land north of Bay View Terrace, Dinas Cross, Pembrokeshire, SA42 0UR Prepared by: RLH Architectural Design Solutions Ltd 16 Main Street Fishguard Pembrokeshire SA65 9HJ Tel: 01348 435004 Enquiries to: [email protected] 12 th July 2019 STATUS : DRAFT FOR PRE -APPLIC ATION CONSULTA TION (PAC) Rev -A On behalf of: Tai Wales & West Housing RLH Architectural Design Solutions Ltd R454 – Propos ed devel opment of land for affordable hous ing on land north of Bay View Terrace, Dinas Cross, Newport, Pembrokeshire, SA42 0UR - Inclusive Design, Access & Sustainability Statement CONTENTS: 1. Appraisal 2. Accessibility 3. Character (including amount, layout, scale, appearance and landscaping) 4. Community Safety 5. Environmental sustainability 6. Movement to, from and within the development APPENDICIES Appendix 1 – Local Authority Pre Application Response (Planning Department). Appendix 2 – Tree & Hedgerow Survey/Report by RDS Landscape Solutions Appendix 3 – Landscape Masterplan by RDS Landscape Solutions Appendix 4 – Ecology Survey/Report by RDS Landscape Solutions Appendix 5 – Geotechnical & Geoenvironmental Site Investigation Report by Terrafirma RLH Architectural Design Solutions Ltd Tel: 01348 435004 - Fax: 01348 871926 - Email: [email protected] - website: www.rlharchitectural.com R454 – Propos ed devel opment of land for affordable hous ing on land north of Bay View Terrace, Dinas Cross, Newport, Pembrokeshire, SA42 0UR - Inclusive Design, Access & Sustainability Statement 1/ APPRAISAL RLH Ltd has been instructed by Tai Wales & West Housing, in respect of an application for full planning permission to Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. -

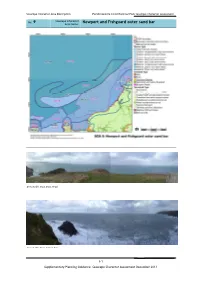

Newport and Fishguard Outer Sand Bar Area Name

Seascape Character Area Description Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Seascape Character Assessment No: 9 Seascape Character Newport and Fishguard outer sand bar Area Name: Area visible from Dinas Head Area visible from Ceibwr Bay 9-1 Supplementary Planning Guidance: Seascape Character Assessment December 2013 Seascape Character Area Description Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Seascape Character Assessment Summary Description This sand bar is located in St George’s Channel on the southern edge of Cardigan Bay running parallel to the coast. It is predominantly medium depth water with shallow water of less than 30m deep to the south west with a sand seabed and low wind. Key Characteristics Shallow to medium depth sand bar parallel to the coast 3-5km from the coast. Sinuous sand banks and channels on the seabed to the south. Generally low wave stress, low tide speed parallel to the coast and slack water inshore. No wrecks. Used for leisure sailing by larger boats and ferries and commercial craft may be visible to the north and south entering Fishguard Harbour. Open sea with simple, open characteristics at a vast scale dominated by swell, waves and winds with a sense of remoteness. The key coastal features are Cemaes Head and Dinas Head with a backcloth of coastal hills including Mynydd Carningli. The lighthouse at Strumble Head would be apparent at night, as would the street lights of Fishguard and the ferry port from closer distances. The sea and much of the coast would be dark. Tranquillity will be reduced by MOD use as a training area. Physical Influences A shallow to medium depth (20-40m) offshore east-west sand bar composed of sand grading offshore into sandy gravel, sloping only gently (<1o) on- and offshore. -

Train Service Requirements

Train Service Requirements Wales and Borders Rail Service and South Wales Metro -Saturdays TSR 1a December 2019 SO Confidentiality TBC Version Final Date 5/23/2018 Wales and Borders Rail and South Wales Metro Saturdays TSR 1a December 2019 SO Confidentiality: TBC Version: Final Date: 5/23/2018 Train Service Requirement tables - Guidance notes This note accompanies the Train Service Requirement (TSR). The TSR sets out the minimum level of service to be provided. The TSR tables in this file relate to the standard Saturday service. Separate TSRs will be provided for: · Weekdays · Saturdays · Sundays The TSR represents the minimum number of direct services required to be operated between specified stations during a specified time interval. The TSR also specifies the latest time at which the first train between two stations must operate, and the earliest time at which the last train between two stations must operate. The Wales and Borders (W&B) network has been divided into nine geographic route sections: · West of Cardiff, between Cardiff and Swansea via the South Wales Main Line (SWML) including the Maesteg branch; · West of Swansea, comprising the SWML west of Swansea, including the Pembroke Dock and Fishguard branches · Heart of Wales Line between Swansea and Shrewsbury; · Cardiff Valley Lines, north of Cardiff sections; · Cardiff Valley Lines, south of Cardiff sections, including the City Line serving Radyr and the Vale of Glamorgan Line serving Rhoose and Bridgend; · East of Cardiff, comprising the route between Cardiff and Gloucester / Cheltenham and the Marches route between Cardiff, Chester and Manchester; · Cambrian, between Birmingham and Aberystwyth and the Cambrian Coast line serving Pwllheli; · North Wales, between Manchester, Llandudno and Holyhead, including the Blaenau Ffestiniog branch and services between Crewe and Chester and between Liverpool and Chester; and · Borderlands, between Wrexham and Bidston. -

Visiting South Hook LNG Terminal

Visitor Information Leaflet_Rev 03 Visiting South Hook LNG Terminal The South Hook LNG Terminal is located in Milford Haven, in the county of Pembrokeshire, West Wales, about 100 miles west of Cardiff. The South Hook LNG Terminal is a receiving and regasification facility. We are an Upper Tier COMAH (Control of Major Accident hazards) regulated site. Safety at the Terminal is our top priority and we ask you to read the following important information in advance of your arrival. Prior to your visit, please inform your host if any of the r CCTV is in operation on site at all times following circumstances apply to you: r Motorcycle helmets, snoods, scarves, balaclavas or r You are classified as a young person (under 18) any similar headwear that covers/partly covers the face r You require any additional support, or have certain should not be worn on site adjustments due to personal circumstances that need to be Safety considered during your visit r All visitors may be required to undertake Drug & Alcohol r In the unlikely event of an emergency, you would need testing. Please bring evidence of any medication you are additional assistance or adjustments in an emergency currently taking or have taken within the past week. Access evacuation to the Terminal may be denied if the Drug & Alcohol test Identification results are positive r Please bring photographic proof of your identity (preferably r You will be required to watch a short introductory DVD, a Passport or Photo Card Driving Licence). If you do not providing you with important safety information have either of these documents please contact your r Your South Hook LNG host will meet you at the Security South Hook LNG host, prior to your arrival at the Terminal Gatehouse on arrival or you will be escorted to them. -

Urban Settlements Report

Urban Settlements Report Development Plans September 2019 1 2 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................. 4 2. Methodology................................................................................................. 5 3. Data Analysis ............................................................................................... 7 4. The Towns Settlement Hierarchy ................................................................ 11 5. Conclusions................................................................................................ 13 Appendix 1 ........................................................................................................ 14 3 1. Introduction 1.1 A study of the availability of Services and Facilities in Pembrokeshire’s Urban and Rural Settlements, identified in the LDP Preferred Strategy (December 2018), is an important part of the evidence base for the development of LDP 2. Understanding the levels of services and facilities provides a clear understanding of the way in which the towns of Pembrokeshire function in order to identify strategies and locations for housing and other development during the life of the Plan. 1.2 According to the draft National Development Framework (Consultation 7 August – 1 November 2019) the Welsh Government “supports the role of the regional centres of Carmarthen, Llandrindod Wells, Newtown, Aberystwyth and the four Haven Towns (Milford Haven, Haverfordwest, Pembroke and Pembroke Dock). These -

Listing Showing Events from 31/05/2012 to 30/06/2012 and Pembrokeshire

Listing showing events from 31/05/2012 to 30/06/2012 and Pembrokeshire Wear your Wellies for Wildlife at Welsh Wildlife Centre Welsh Wildlife Centre, Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales, Cilgerran, Cardigan, Pembrokeshire, SA43 2TB 31st May 2012 Contact: Enquiries Tel: 01239 621600 Email: [email protected] Web: www.welshwildlife.org/wwcIntro_en.link £1 per person Car park fee £3, free to members of Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales The idea is simple: all we ask you do is get as many of your staff, friends, family as possible to pay £1 to wear their wellies for a day, afternoon or even an hour! Fishguard Folk Festival at Fishguard Fishguard, Fishguard, Pembrokeshire, SA64 0DE 1st Jun 2012 - 4th Jun 2012 00:00 - 00:00 and 00:00 - 00:00 Contact: Enquiries Web: www.pembrokeshire-folk-music.co.uk/Festival.htm The 13th annual celebration of folk music, song and dance... Fishguard Farmers Market at Fishguard Fishguard, Fishguard, Pembrokeshire, SA64 0DE 2nd Jun 2012 09:00 - 13:00 and 00:00 - 00:00 9th Jun 2012 09:00 - 13:00 and 00:00 - 00:00 16th Jun 2012 09:00 - 13:00 and 00:00 - 00:00 23rd Jun 2012 09:00 - 13:00 and 00:00 - 00:00 30th Jun 2012 09:00 - 13:00 and 00:00 - 00:00 Contact: Enquiries Tel: 01437 532277 Eggs, bread, cheese, honey, butter, poultry, meat, trout, herbs, vegetables, plants, soft fruit, preserves, baked goods, cakes, chutneys, organic produce, herbal soaps and sheepskins Pembroke Farmers Market at Pembroke Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, SA61 1TP 2nd Jun 2012 09:30 - 13:30 16th Jun 2012 09:30 - 13:30 30th Jun 2012 09:30 - 13:30 Contact: Enquiries Tel: 01446 771033 The Pembroke Farmers Market provides customers with locally produced meats, baked goods, fresh produce, and other foods and arts and crafts.