International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pemanfaatan Media Streaming Youtube Oleh Gemilang Tv Sebagai Wadah Informasi Indragiri Hilir

NOMOR SKRIPSI No. 4081/KOM-D/SD-S1/2020 PEMANFAATAN MEDIA STREAMING YOUTUBE OLEH GEMILANG TV SEBAGAI WADAH INFORMASI INDRAGIRI HILIR SKRIPSI Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Dakwah dan Komunikasi Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau Untuk Memenuhi Sebagai Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Strata Satu (S1) Ilmu Komunikasi (S.I.Kom) OLEH: RIZKY YUDIHASTIRA NIM: 11543104554 PROGRAM STUDI ILMU KOMUNIKASI FAKULTAS DAKWAH DAN KOMUNIKASI UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SULTAN SYARIF KASIM RIAU 2020 ABSTRAK Nama : Rizky Yudihastira Program Studi : Ilmu Komunikasi Judul : Pemanfaatan Media Streaming Youtube Oleh Gemilang TV Sebagai Wadah Informasi Indragiri Hilir Televisi sebagai salah satu media elektronik yang selalu mengalami perubahan dan inovasi dalam melakukan siaran, ini disebabkan karena banyak fenomena media baru (new media) yang saat ini bermunculan, salah satunya adalah adanya media berbasis video streaming. Salah satu yang memiliki fitur video streaming tersebut adalah YouTube. Salah satu stasiun televisi yang memanfaatkan YouTube sebagai sarana untuk melakukan siaran adalah Gemilang TV Tembilahan, dimana channel YouTube Gemilang TV aktif dalam memberikan informasi seputar kabar Indragiri Hilir. Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui bagaimana pemanfaatan media streaming YouTube oleh Gemilang TV sebagai wadah informasi Indragiri Hilir. Teori dan konsep yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah teori new media dan konsep pemanfaatan Chin dan Todd dengan 5 indikator pemanfaatan. Pendekatan yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini -

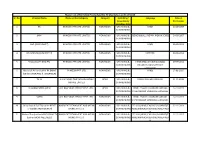

Downlinkin/ Uplinking Only Language Date of Permission 1 9X 9X ME

Master List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 31.07.2018 Sr. No. Channel Name Name of the Company Category Upliniking/ Language Date of Downlinkin/ Permission Uplinking Only 1 9X 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 24-09-2007 DOWNLINKING 2 9XM 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS HINDI/ENGLISHUPLINKING & /BENGALI&ALL INDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE 24-09-2007LANGUAGE DOWNLINKING 3 9XO (9XM VELVET) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING 4 9X JHAKAAS (9X MARATHI) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & MARATHI 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING 5 9X JALWA (PHIR SE 9X) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI/ENGLISH /BENGALI&ALL 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING INDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 6 Housefull Action (earlier 9X BAJAO 9X MEDIA PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 17-01-2015 (Earlier 9X BAJAAO & 9X BANGLA) DOWNLINKING 7 TV 24 A ONE NEWS TIME BROADCASTING NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI/ PUNJABI/ ENGLISH 21-10-2008 PRIVATE LIMITED DOWNLINKING 8 BHASKAR NEWS (AP 9) A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 DOWNLINKING OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 9 SATYA A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 DOWNLINKING OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 10 Shiva Shakthi Sai TV (earlier BENZE AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING & TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 TV (Earlier AADRI ENRICH) WORKS PVT.LTD. DOWNLINKING AMIL/KANNADA/BENGALI/MALAYALA M 11 Mahua Plus (earlier AGRO ROYAL TV AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING & TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 (Earlier AADRI WELLNESS) WORKS PVT.LTD. -

PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK/AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES

PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK/AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN/ CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 MARET 2016 DAN 31 DESEMBER 2015 SERTA PERIODE TIGA BULAN YANG BERAKHIR 31 MARET 2016 DAN 2015 MARCH 31, 2016 AND DECEMBER 31, 2015 AND FOR THREE MONTHS PERIOD ENDED MARCH 31, 2016 AND 2015 PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES DAFTAR ISI TABLE OF CONTENTS Halaman/ Page SURAT PERNYATAAN DIREKSI DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT LETTER LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN – Pada CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - As of tanggal 31 Maret 2016 dan 31 Desember 2015 March 31, 2016 and December 31, 2015 and for serta untuk periode tiga bulan yang berakhir three months period ended March 31, 2016 and 2015 31 Maret 2016 dan 2015 Laporan Posisi Keuangan Konsolidasian 2 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position Laporan Laba Rugi Komprehensif Konsolidasian 4 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income Laporan Perubahan Ekuitas Konsolidasian 5 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity Laporan Arus Kas Konsolidasian 6 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows Catatan atas Laporan Keuangan Konsolidasian 7 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES LAPORAN POSISI KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL POSITION 31 MARET 2016 DAN 31 DESEMBER 2015 MARCH 31, 2016 AND DECEMBER 31, 2015 (Angka dalam tabel dinyatakan dalam jutaan Rupiah) (Figures in tables are -

PT SURYA CITRA MEDIA Tbk DAN ANAK PERUSAHAAN CATATAN ATAS LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASI

PT SURYA CITRA MEDIA Tbk DAN ANAK PERUSAHAAN CATATAN ATAS LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASI (Tidak diaudit) Untuk Periode Enam Bulan yang Berakhir Pada Tanggal 30 Juni 2007 Dengan Angka Perbandingan Untuk Enam Bulan Yang Berakhir Pada Tanggal 30 Juni 2006 (Disajikan dalam ribuan Rupiah, kecuali dinyatakan lain) 1. UMUM a. Pendirian Perusahaan PT Surya Citra Media Tbk (“Perusahaan”) didirikan di Indonesia pada tanggal 29 Januari 1999 berdasarkan Akta Notaris Umar Saili, S.H., Notaris di Tangerang, No. 3 pada tanggal yang sama dengan nama PT Cipta Aneka Selaras. Akta pendirian ini disahkan oleh Menteri Kehakiman Republik Indonesia dalam Surat Keputusan C-18033 HT.01.01.Th.99 tanggal 25 Oktober 1999 dan diumumkan dalam Berita Negara No. 9 tanggal 29 Januari 2002 Tambahan No. 997. Anggaran dasar Perusahaan telah mengalami beberapa kali perubahan, diantaranya mengenai perubahan nama Perusahaan dari PT Cipta Aneka Selaras menjadi PT Surya Citra Media berdasarkan Akta Notaris Aulia Taufani, S.H., pengganti Sutjipto, S.H., Notaris di Jakarta, No. 103 tanggal 31 Desember 2001. Perubahan Anggaran Dasar ini telah disetujui oleh Menteri Kehakiman dan Hak Asasi Manusia Republik Indonesia dalam Surat Keputusan No. C-00124 HT.01.04.TH.2002 tanggal 4 Januari 2002 dan diumumkan dalam Berita Negara No. 47 tanggal 11 Juni 2002 Tambahan No. 5690. Perubahan terakhir Anggaran Dasar Perusahaan dilakukan dengan Akta Notaris Aulia Taufani, S.H., pengganti Sutjipto, S.H., Notaris di Jakarta, No. 164 tanggal 25 April 2003 mengenai perubahan komposisi pemegang saham. Perubahan Anggaran Dasar ini telah dilaporkan dan diketahui oleh Menteri Kehakiman dan Hak Asasi Manusia Republik Indonesia dalam Surat Penerimaan Laporan No. -

Democracy in Indonesia 1

Democracy in Indonesia 1 Democracy in Indonesia A Survey of the Indonesian Electorate 2003 141103-INTRODUCTION 1 11/17/03, 7:48 PM 2 Democracy in Indonesia Democracy in Indonesia 3 141103-INTRODUCTION 2 11/17/03, 7:48 PM 2 Democracy in Indonesia Democracy in Indonesia 3 Democracy in Indonesia A Survey of the Indonesian Electorate 2003 Project Director and Editor: Tim Meisburger The Asia Foundation Editorial Board: Douglas Ramage, Roderick Brazier, Robin Bush, Hana Satriyo, Zacky Husein, Kelly Deuster, Wandy N. Tuturoong, Sandra Hamid Questionnaire Design: Craig Charney – Charney Research Report: Craig Charney, Nicole Yakatan, and Amy Marsman – Charney Research Research and Fieldwork: Farquhar Stirling, Achala Srivasta, Eko Wicaksono, Safril Faried, Dindin Kusdinar, Rocky Hatibie – ACNielsen Indonesia 141103-INTRODUCTION 3 11/17/03, 7:48 PM 4 Democracy in Indonesia Democracy in Indonesia 5 About The Asia Foundation The Asia Foundation is a non-profit, non-governmental organization committed to the development of a peaceful, prosperous, and open Asia-Pacific region. The Foundation supports programs in Asia that help improve governance and law, economic reform and development, women’s participation, and international relations. Drawing on nearly 50 years of experience in Asia, the Foundation collaborates with private and public partners to support leadership and institutional development, technical assistance, exchanges, policy research, and educational material. With a network of 17 offices throughout Asia, an office in Washington, D.C., and headquarters in San Francisco, the Foundation addresses these issues on country and regional levels. In the past fiscal year of 2002, the Foundation provided grants, educational materials, and other resources of more than $50 million to 22 countries and territories in Asia and through its Books for Asia program has distributed over 750,000 books to over 4,000 schools and other regional educational institutions. -

Proses Produksi Program Berita Jawa Timur Dalam Berita Di Tvri Stasiun Jawa Timur

Laporan Kuliah Kerja Media PROSES PRODUKSI PROGRAM BERITA JAWA TIMUR DALAM BERITA DI TVRI STASIUN JAWA TIMUR Disusun Oleh : ARDITO YULIADHI D 1405061 TUGAS AKHIR Ditujukan Untuk Melengkapi Tugas-Tugas dan Memenuhi Syarat-Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Ahli Madya D3 Komunikasi Terapan PROGRAM D3 KOMUNIKASI TERAPAN FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SEBELAS MARET SURAKARTA 2008 PERSETUJUAN Tugas Akhir berjudul : PROSES PRODUKSI PROGRAM BERITA “JAWA TIMUR DALAM BERITA” DI TVRI STASIUN JAWA TIMUR. Disusun Oleh : Nama : Ardito Yuliadhi NIM : D1405061 Konsentrasi : Penyiaran Disetujui untuk dipertahankan dihadapan panitia penguji Tugas Akhir Program D3 Komunikasi Terapan Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta. Surakarta, 2 Juni 2008 Menyetujui, Dosen Pembimbing Chatarina Heny Dwi S, S.Sos NIP : 132.300.217 DAFTAR ISI HALAMAN JUDUL …………………………………………………………………i HALAMAN PERSETUJUAN ……………………………………………………....ii HALAMAN PENGESAHAN ……………………………………………………….iii HALAMAN MOTTO ………………………………………………………………..iv HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN ……………………………………………………..v KATA PENGANTAR ……………………………………………………………….vi DAFTAR ISI ……………………………………………………………………….viii BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang …………………………………………………………….1 B. Tujuan Kuliah Kerja Media ……………………………………………….3 BAB II TINJAUAN PUSTAKA A. Berita Secara Umum ………………………………………………………4 a. Pengertian Berita ………………………………………………………..4 b. Nilai Berita ………………………………………………………………6 c. Sumber Berita …………………………………………………………...7 d. Jenis Berita ………………………………………………………………9 B. Berita Media Elektronik -

List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels As on 20.7.2016 Sr

List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 20.7.2016 Sr. No. Channel Name Name of the Company Category Upliniking/Down Language Date of Permission linkin/ Uplinking Only 1 9X 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI 24/09/2007 2 9XM 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI/ENGLISH 24/09/2007 3 9XO (9XM VELNET) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI 29/09/2011 4 9X JHAKAAS (9X 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING MARATHI 29/09/2011 MARATHI) 5 9X JALWA (PHIR SE 9X) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI 29/09/2011 6 9X BAJAO (Earlier 9X 9X MEDIA PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI 17/01/2015 BAJAAO & 9X BANGLA) 7 TV 24 A ONE NEWS TIME NEWS UPLINKING HINDI/ PUNJABI/ ENGLISH 21/10/2008 BROADCASTING PRIVATE LIMITED 8 BHASKAR NEWS (AP 9) A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. NEWS UPLINKING HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND 14/10/2011 LTD. ALL OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 9 SATYA A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND 14/10/2011 LTD. ALL OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 10 BENZE TV (Earlier AADRI AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND NON-NEWS UPLINKING TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJAR 22/11/2011 ENRICH) MEDIA WORKS PVT.LTD. ATI/TAMIL/KANNADA/BENGALI /MALAYALAM 11 AGRO ROYAL TV (Earlier AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND NON-NEWS UPLINKING TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJAR 22/11/2011 AADRI WELLNESS) MEDIA WORKS PVT.LTD. ATI/TAMIL/KANNADA/BENGALI /MALAYALAM 12 ABN ANDHRA JYOTHI AAMODA BROADCASTING NEWS UPLINKING TELUGU 30/06/2009 COMPANY PRIVATE LIMITED 13 ANJAN TV AAP MEDIA PVT.LTD. -

PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK/AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES

PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK/AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN/ CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 30 JUNI 2020 DAN 31 DESEMBER 2019 SERTA PERIODE ENAM BULAN YANG BERAKHIR 30 JUNI 2020 DAN 2019/ JUNE 30, 2020 AND DECEMBER 31, 2019 AND FOR THE SIX MONTHS PERIOD ENDED JUNE 30, 2020 AND 2019 PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES DAFTAR ISI TABLE OF CONTENTS Halaman/ Page SURAT PERNYATAAN DIREKSI DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT LETTER LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN – Pada CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - As of tanggal 30 Juni 2020 dan 31 Desember 2019 serta June 30, 2020 and December 31, 2019 and for the untuk periode enam bulan yang berakhir six months period ended June 30, 2020 and 2019 30 Juni 2020 dan 2019 Laporan Posisi Keuangan Konsolidasian 1 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position Laporan Laba Rugi Komprehensif Konsolidasian 3 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income Laporan Perubahan Ekuitas Konsolidasian 4 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity Laporan Arus Kas Konsolidasian 5 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows Catatan atas Laporan Keuangan Konsolidasian 6 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAK PT. MEDIA NUSANTARA CITRA Tbk AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES LAPORAN POSISI KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL POSITION 30 JUNI 2020 DAN 31 DESEMBER 2019 JUNE 30, 2020 AND DECEMBER 31, 2019 (Angka dalam tabel dinyatakan dalam jutaan Rupiah) (Figures in tables are stated -

Pt Media Nusantara Citra

MEMEMMIIMMPINPIN DANDAN MMENGINSPIRASIENGINSPIRASI LEADING AND INSPIRING PT Global Mediacom Tbk (MCOM/Perseroan), melalui dua unit bisnis PT Global Mediacom Tbk (MCOM/the Company), through its two utamanya PT Media Nusantara Citra Tbk (MNC) dan PT MNC Sky core operating companies PT Media Nusantara Citra Tbk (MNC) and Vision Tbk (MSKY), adalah pemimpin pasar Indonesia dalam industri PT MNC Sky Vision Tbk (MSKY), is the Indonesian market leader in televisi free-to-air (FTA) dan TV berlangganan. Tahun ini, ketiga TV free-to-air (FTA) television and pay-TV. This year, our three FTA TV FTA kami menikmati pangsa pemirsa prime time kumulatif sebesar stations enjoyed a combined prime time audience share of 40.1%. 40,1%. Ketiga merek TV berlangganan kami secara kolektif menguasai Our three pay-TV brands collectively accounted for 74% of all pay-TV 74% pasar TV berlangganan di Indonesia. Kami menjadi yang terdepan subscribers in Indonesia. We hold a commanding position within the dalam industri media Indonesia dan kami bertujuan menggunakan Indonesian media industry, and we aim to use this hard-won position posisi yang diraih dengan kerja keras ini untuk menginspirasi dan to inspire and benefit others. memberi manfaat bagi orang lain. Kami mencapai posisi di sini melalui penerapan rangkaian strategi We arrived at this position through our teams’ skillful implementation inovatif dan terkalkulasi tim kami. Perseroan mengedepankan nilai of innovative and calculated strategies. Our Company holds the values keuletan, kerja keras dan pandangan berorientasi ke depan. Dengan of perseverance, hard work and progressive thinking at its core. With nilai-nilai ini, kami memimpin industri media nasional dan telah these values we lead the domestic media industry, and have won the memenangkan rasa kagum dari pemangku kepentingan dan rasa admiration of our stakeholders and the respect of our competitors. -

Kecanduan Sinetron India Pada Siaran Andalas Televisi (ANTV

PENGESAHAN SKRIPSI Skripsi yang berjudul “Kecanduan Sinetron India pada Siaran Andalas Televisi (ANTV) Warga Kelurahan Balandai Kecamatan Bara kota Palopo” yang ditulis oleh Jefri, dengan (NIM) 14.16.6.0009, Mahasiswa Program Studi Komunikasi dan Penyiaran Islam, Fakultas Ushuluddin, Adab, dan Dakwah. Institut Agama Islam Negeri (IAIN) Palopo, yang dimunaqasyahkan pada hari Senin, 20 Agustus 2018 M, bertepatan dengan 8 Dzulhijjah 1439 H, telah diperbaiki sesuai dengan catatan dan permintaan tim penguji, dan diterima sebagai syarat memperoleh gelar Sarjana Sosial (S.Sos.). Palopo, 20 Agustus 2018 M 8 Dzulhijjah 1439 H Tim Penguji 1. Dr. Efendi P., M.Sos.I. Ketua Sidang ( ) 2. Dr. H. M. Zuhri Abu Nawas, Lc., M.A. Sekretaris Sidang ( ) 3. Dr. Masmuddin, M.Ag. Penguji I ( ) 4. Dr. H. M. Zuhri Abu Nawas, Lc., M.A. Penguji II ( ) 5. Dr. Abdul Pirol, M.Ag. Pembimbing I ( ) 6. Wahyuni Husain, S.Sos., M.I.Kom. Pembimbing II ( ) Mengetahui, Rektor IAIN Palopo Dekan Fakultas Ushuluddin, Adab, dan Dakwah Dr. Abdul Pirol, M.Ag. Dr. Efendi P., M.Sos.I. NIP 19691104 199403 1 004 NIP 19651231 199803 1 009 PRAKATA 1 2 ا ْل َح ْمدُ ِلل ِه َر ِّب اْلعَال ِم ْي َن َوال َّص ََلةُ َوال ّس ََل ُم َع َلى اَ ْش َر ِف اْ ْﻻ ْنبِيَا ِء وا ْل ُم ْر َس ِل ْي َن َس يِّ ِدنَا ُم َح َّم ٍد َو َع َلى اَ ِل ِه َواَ ْصحاَبِ ِه اَ ْج َم ِع ْي َن Puji dan syukur penulis panjatkan hadirat Allah swt. Atas segala rahmat dan karunia-Nya sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi yang berjudul “Kecanduan Sinetron India pada Siaran Andalas Televisi (ANTV) Warga Kelurahan Balandai Kecamatan Bara Kota Palopo” guna diajukan sebagai salah satu syarat untuk mencapai gelar Sarjana Sosial (S.Sos) pada Institut Agama Islam Negeri (IAIN) Palopo. -

PT MNC Studios International Tbk. Company Presentation To

PT MNC Studios International Tbk (“MSIN”) Public Expose May 2021 Listed and traded on the Indonesia Stock Exchange | STOCK CODE: MSIN0 Corporate Structure PT MNC Tbk (MNCN) PT MSI Tbk (MSIN) Content Distribution Mediate Indonesia MNC Infotainment Asia Media Productions MNC Pictures MNC Film Indonesia Star Media Nusantara MNC Lisensi Internasional Esports Star Indonesia MNC Animation/Games Multi Media Integrasi MNC Movieland Indonesia Swara Bintang Abadi Suara Mas Abadi Star Cipta Musikindo 1 MNC Pictures: Drama Production • MNC Pictures produces all types of drama content format, such as drama series, FTV, sitcoms and web series on social media platforms and is the primary supplier of drama series to RCTI and MNCTV. • Capitalize on the demand for digital-based entertainment by producing high-quality short and medium form content including web series for social media platforms. • MNC Pictures also produces original content for Vision + and RCTI +, including Skripsick, 4 Sekawan Sebelum Dunia Terbalik, Ada Dewa Di Sisiku, Sebelum Dunia Terbalik, dan Nikah Duluan. Drama Series Production Market Share – 4M/21 • Aired since October 2020 • Aired since April 2021 • Best performing drama series ever to air on FTA TV • Best Ramadan Special Series • Average performance up to April 2021: • Average Performance: Tobali • Rating : 4.6% • Rating : 11.4% 5% Others • Audience Share : 41.6% • Audience Share : 36.3% • Highest Performance: 9% • Highest Performance: Screenplay • Rating : 5.3% • Rating : 14.8% 3% • Audience Share : 51.5% • Audience Share : 42.9% 41% Original Content Mega Kreasi • Aired since May 2017 18% • The best current comedy drama series with an average performance: Sinemart • Rating : 4.7% 24% • Audience Share : 26.1% • Highest Performance: • Rating : 6.3% • Audience Share : 30.7% MNC Pictures Sinemart Mega Kreasi Screenplay Tobali Others 2 MNC Pictures – Top Program • Content is the key to win the audience market share in the television industry. -

Kantor Berita Radio (KBR) End Line Report

Kantor Berita Radio (KBR) end line report MFS II country evaluations, Civil Society component Dieuwke Klaver1 Hester Smidt1 Kharisma Nugroho2 Sopril Amir2 1 Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR, Netherlands 2 SurveyMETER, Indonesia Centre for Development Innovation Wageningen, February 2015 Report CDI-15-024 Klaver, D.C., Smith H., Nugroho K., Amir S., February 2015, KBR end line report; MFS II country evaluations, Civil Society component, Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR (University & Research centre) and SurveyMETER. Report CDI-15-024. Wageningen. This report describes the findings of the end line assessment of the Kantor Berita Radio 68H (KBR68H), a partner of Free Press Unlimited in Indonesia. The evaluation was commissioned by NWO-WOTRO, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research in the Netherlands and is part of the programmatic evaluation of the Co-Financing System - MFS II financed by the Dutch Government, whose overall aim is to strengthen civil society in the South as a building block for structural poverty reduction. Apart from assessing impact on MDGs, the evaluation also assesses the contribution of the Dutch Co-Funding Agencies to strengthen the capacities of their Southern Partners, as well as the contribution of these partners towards building a vibrant civil society arena. This report assesses how KBR68H has contributed towards strengthening civil society in Indonesia using the CIVICUS analytical framework. It is a follow-up of a baseline study conducted in 2012. Key questions that are being answered relate to changes in the five CIVICUS dimensions to which KBR68H contributed; the nature of its contribution; the relevance of the contribution made, and an identification of factors that explain KBR68H’s role in civil society strengthening.