Canada and the Race for Asia (PDF, 60

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Internship Programme 2020-21 Annual Report

Parliamentary Internship Programme 2020-21 Annual Report Annual General Meeting Canadian Political Science Association June 11, 2021 Dr. Paul Thomas Director Web: pip-psp.org Twitter: @PIP_PSP Instagram: @pip-psp Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ParlInternship/ PIP Annual Report 2021 Director’s Message I am delighted to present the Parliamentary Internship Programme’s (PIP) 2020-21 Annual Report to the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA). The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically reshaped the experience of the 2020-21 internship cohort relative to previous years. Such changes began with a mostly-virtual orientation in September, and continued with remote work in their MP placements, virtual study tours, and Brown-Bag lunches over Zoom. Yet while limiting some aspects of the PIP experience, the pandemic provided opportunities as well. The interns took full advantage of the virtual format to meet with academics, politicians, and other public figures who were inaccessible to previous cohorts relying on in-person meetings. They also learned new skills for online engagement that will serve them well in the hybrid work environment that is emerging as COVID-19 recedes. One thing the pandemic could not change was the steadfast support of the PIP’s various partners. We are greatly indebted to our sponsors who chose to prioritize their contributions to PIPs despite the many pressures they faced. In addition to their usual responsibilities for the Programme, both the PIP’s House of Commons Liasion, Scott Lemoine, and the Programme Assistant, Melissa Carrier, also worked tirelessly to ensure that the interns were kept up to date on the changing COVID guidance within the parliamentary preccinct, and to ensure that they had access to the resources they needed for remote work. -

Big Oil's Oily Grasp

Big Oil’s Oily Grasp The making of Canada as a Petro-State and how oil money is corrupting Canadian politics Daniel Cayley-Daoust and Richard Girard Polaris Institute December 2012 The Polaris Institute is a public interest research organization based in Canada. Since 1997 Polaris has been dedicated to developing tools and strategies to take action on major public policy issues, including the corporate power that lies behind public policy making, on issues of energy security, water rights, climate change, green economy and global trade. Polaris Institute 180 Metcalfe Street, Suite 500 Ottawa, ON K2P 1P5 Phone: 613-237-1717 Fax: 613-237-3359 Email: [email protected] www.polarisinstitute.org Cover image by Malkolm Boothroyd Table of Contents Introduction 1 1. Corporations and Industry Associations 3 2. Lobby Firms and Consultant Lobbyists 7 3. Transparency 9 4. Conclusion 11 Appendices Appendix A, Companies ranked by Revenue 13 Appendix B, Companies ranked by # of Communications 15 Appendix C, Industry Associations ranked by # of Communications 16 Appendix D, Consultant lobby firms and companies represented 17 Appendix E, List of individual petroleum industry consultant Lobbyists 18 Appendix F, Recurring topics from communications reports 21 References 22 ii Glossary of Acronyms AANDC Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada CAN Climate Action Network CAPP Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers CEAA Canadian Environmental Assessment Act CEPA Canadian Energy Pipelines Association CGA Canadian Gas Association DPOH -

AB Today – Daily Report August 25, 2020

AB Today – Daily Report August 25, 2020 Quotation of the day “With [Jason] Kenney and [Andrew] Scheer, it was clear that Scheer was the little brother and Kenney dominated that relationship.” Mount Royal University political science professor Duane Bratt tells AB Today Erin O’Toole has the challenge of having to make a name for himself as CPC leader. Today in AB On the schedule The swearing-in ceremony for Alberta’s first-ever Muslim lieutenant-governor, Salma Lakhani, will take place on Wednesday in the legislature. Finance Minister Travis Toews’ economic update to the legislative assembly happens on Thursday. O’Toole stresses need for national unity in phone call with Trudeau With the election of Erin O’Toole as the Conservative Party of Canada’s new leader, Premier Jason Kenney has a powerful new ally in Ottawa. In Monday’s inaugural call between O’Toole and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the newly minted CPC leader raised the issue of western alienation and warned that national unity must be addressed in the PM’s upcoming throne speech next month. These were warm words to Kenney — who backed O’Toole and was the only premier to publicly endorse a CPC leadership candidate. “Albertans remember that Mr. Trudeau openly campaigned against this province and its largest industry in the last election,” Kenney said. In an interview with AB Today, Mount Royal University political science professor Duane Bratt said O’Toole’s time and effort winning over Alberta Tories helped win him the tight race. “The signalling Kenney did also help him with conservatives elsewhere,” Bratt said. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

Core 1..31 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 38e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 134 No 134 Friday, October 7, 2005 Le vendredi 7 octobre 2005 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Mitchell La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Mitchell (Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food), seconded by Mr. Brison (ministre de l'Agriculture et de l'Agroalimentaire), appuyé par M. (Minister of Public Works and Government Services), — That Bill Brison (ministre des Travaux publics et des Services S-38, An Act respecting the implementation of international trade gouvernementaux), — Que le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant commitments by Canada regarding spirit drinks of foreign la mise en oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris countries, be now read a second time and referred to the par le Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. étrangers, soit maintenant lu une deuxième fois et renvoyé au Comité permanent de l'agriculture et de l'agroalimentaire. The debate continued. Le débat se poursuit. The question was put on the motion and it was agreed to. La motion, mise aux voix, est agréée. Accordingly, Bill S-38, An Act respecting the implementation En conséquence, le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant la mise en of international trade commitments by Canada regarding spirit oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris par le drinks of foreign countries, was read the second time and referred Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays étrangers, est to the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. -

Debates of the House of Commons

43rd PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION House of Commons Debates Official Report (Hansard) Volume 150 No. 076 Thursday, March 25, 2021 Speaker: The Honourable Anthony Rota CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 5225 HOUSE OF COMMONS Thursday, March 25, 2021 The House met at 10 a.m. port of the Standing Committee on the Status of Women, entitled “Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women”. Prayer Pursuant to Standing Order 109, the committee requests that the government table a comprehensive response to this report. ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS * * * [Translation] ● (1005) [English] CANADA SHIPPING ACT FEDERAL-PROVINCIAL FISCAL ARRANGEMENTS ACT Hon. Chrystia Freeland (Deputy Prime Minister and Minis‐ Mr. Maxime Blanchette-Joncas (Rimouski-Neigette—Témis‐ ter of Finance, Lib.) moved for leave to introduce Bill C-25, An couata—Les Basques, BQ) moved for leave to introduce Act to amend the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act, to Bill C-281, An Act to amend the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 (cer‐ authorize certain payments to be made out of the Consolidated Rev‐ tificate of competency). enue Fund and to amend another Act. (Motions deemed adopted, bill read the first time and printed) He said: Mr. Speaker, this morning, I am pleased to introduce a * * * bill to amend the Canada Shipping Act, 2001. COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE This legislative measure will address head-on the labour shortage PUBLIC SAFETY AND NATIONAL SECURITY in the marine industry, which is a major concern. A foreign national Hon. John McKay (Scarborough—Guildwood, Lib.): Mr. who holds a diploma from a recognized school, such as the Institut Speaker, I have the honour to present, in both official languages, maritime du Québec in Rimouski, will now also be able to benefit the fifth report of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and Na‐ from the privileges that come with the certificate of competency tional Security in relation to the main estimates 2021-22, and re‐ and sail on the majestic St. -

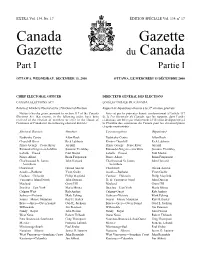

Canada Gazette, Part I, Extra

EXTRA Vol. 134, No. 17 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 134, no 17 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2000 OTTAWA, LE MERCREDI 13 DÉCEMBRE 2000 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members Elected at the 37th General Election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 37e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been delaLoi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Etobicoke Centre Allan Rock Etobicoke-Centre Allan Rock Churchill River Rick Laliberte Rivière Churchill Rick Laliberte Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Assiniboia Assiniboia Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Vancouver Island North John Duncan Île de Vancouver-Nord John Duncan Macleod Grant Hill Macleod Grant Hill Beaches—East York Maria Minna Beaches—East York Maria Minna Calgary West Rob Anders Calgary-Ouest Rob Anders Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Souris—Moose Mountain Roy H. -

Canada Seen to ‘Dial News MP Expenses P

TWENTY-NINTH YEAR, NO. 1543 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER WEDNESDAY, JUNE 20, 2018 $5.00 Transport Out with media Ex- Minister bus, old-style ambassadors Garneau campaign weigh in onTrudeau’s names new strategy: Conservative fortunes approach to chief of Delacourt benefi t from Scheer, Trump p. 4 staff p.18 p. 11 Bernier on same team: Powers p. 11 News Phoenix pay systemNews Foreign aff airs News Legislation Unions Canada seen to ‘dial Extreme swamped partisanship by Phoenix, back’ UN Security to blame for hiring staff to sustained keep afl oat Council bid, say insiders, spike in time ‘It’s just been allocation, overwhelming,’ says all ‘rhetoric,’ no action ex-MPs say CAPE leader Greg Phillips as government ‘The challenge is for announces a union people to actually act partnership to fi nd like grown-ups, work a new pay system. behind the scenes,’ says former Conservative BY EMILY HAWS House leader Jay Hill. everal public sector unions Ssay they’re struggling to deal BY SAMANTHA WRIGHT ALLEN with the fallout of the Phoenix pay system, needing to bring on more The Liberal government’s staff to help manage the workload increasing use of time allocation brought on by their members having to shorten debate, combined with pay issues for more than two years. opposition parties’ procedural tac- Public Service Alliance of tics to eat up time reveals a broken Canada (PSAC) national president relationship between House lead- Chris Aylward said in an emailed ers, say some of their predecessors statement that handing Phoenix is who described a more collegial having a “monumental impact on atmosphere in their day. -

Core 1..148 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 145 Ï NUMBER 031 Ï 3rd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, April 22, 2010 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 1827 HOUSE OF COMMONS Thursday, April 22, 2010 The House met at 10 a.m. [Translation] OLD AGE SECURITY ACT Prayers Mrs. Carole Freeman (Châteauguay—Saint-Constant, BQ) moved for leave to introduce Bill C-516, An Act to amend the Old Age Security Act (application for supplement, retroactive payments and other amendments). ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS She said: Mr. Speaker, I am very proud to introduce this bill, Ï (1000) which would increase the guaranteed income supplement paid to our [English] poorest seniors and ensure that pension benefits are paid to individuals whose spouse or common-law partner has died. GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS The Bloc Québécois believes that the living conditions and dignity Mr. Tom Lukiwski (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of of seniors are not only major issues for society but are also matters of the Government in the House of Commons, CPC): Mr. Speaker, social justice. pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), I have the honour to table, in both official languages, the government's response to 15 petitions. Since income is the most important determining factor in a *** senior's well-being, we, as a society, must ensure that our seniors have a decent income that enables them to participate fully as CRIMINAL CODE citizens. Hon. Jay Hill (for the Minister of Justice and Attorney (Motions deemed adopted, bill read the first time and printed) General of Canada) moved for leave to introduce Bill C-16, An Act to amend the Criminal Code. -

Core 1..182 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 9.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 141 Ï NUMBER 162 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, June 1, 2007 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 10023 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, June 1, 2007 The House met at 10 a.m. We all know about the epic battles that have been fought to enable people to exercise their right to vote. Consider women, who, after quite some time, managed to get the right to vote in Canada and Quebec—even later in Quebec than in Canada. Even today, in other Prayers countries, people are forced to fight for the right to vote. And I mean fight physically. Some people have to go to war to bring democracy to their country. I have seen places where armed guards had to GOVERNMENT ORDERS supervise polling stations so that people could vote. So we in Canada are pretty lucky to have the right to vote. Our democracy enables Ï (1005) people to choose who will represent them at various levels of [Translation] government. Unfortunately, there are still places in the world where people cannot do that. CANADA ELECTIONS ACT The House resumed from May 31 consideration of the motion that Bill C-55, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act (expanded voting opportunities) and to make a consequential amendment to the Referendum Act, be read the second time and referred to a committee. -

Les Débats De La Chambre Des Communes

43e LÉGISLATURE, 2e SESSION Débats de la Chambre des communes Compte rendu officiel (Hansard) Volume 150 No 076 Le jeudi 25 mars 2021 Présidence de l'honorable Anthony Rota TABLE DES MATIÈRES (La table des matières quotidienne des délibérations se trouve à la fin du présent numéro.) 5225 CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES Le jeudi 25 mars 2021 La séance est ouverte à 10 heures. minine, intitulé « Répercussions de la pandémie de COVID‑19 sur les femmes ». Prière Conformément à l'article 109 du Règlement, le Comité demande que le gouvernement dépose une réponse globale à ce rapport. AFFAIRES COURANTES * * * ● (1005) [Français] [Traduction] LA LOI SUR LA MARINE MARCHANDE DU CANADA LA LOI SUR LES ARRANGEMENTS FISCAUX ENTRE LE GOUVERNEMENT FÉDÉRAL ET LES PROVINCES M. Maxime Blanchette-Joncas (Rimouski-Neigette—Témis‐ L’hon. Chrystia Freeland (vice-première ministre et ministre couata—Les Basques, BQ) demande à présenter le projet de loi des Finances, Lib.) demande à présenter le projet de loi C‑25, Loi C‑281, Loi modifiant la Loi de 2001 sur la marine marchande du modifiant la Loi sur les arrangements fiscaux entre le gouverne‐ Canada (brevet d'aptitude). ment fédéral et les provinces, autorisant certains paiements sur le Trésor et modifiant une autre loi. — Monsieur le Président, ce matin, j'ai le plaisir de déposer un (Les motions sont réputées adoptées, le projet de loi est lu pour projet de loi modifiant la Loi de 2001 sur la marine marchande du la première fois et imprimé.) Canada. * * * Précisément, cette mesure législative s'attaquera de front à la pré‐ LES COMITÉS DE LA CHAMBRE occupation majeure de la pénurie de main-d'œuvre dans l'industrie SÉCURITÉ PUBLIQUE ET NATIONALE maritime. -

Meladv June25-2021

THE MELVILLE Friday, $1.50 PER COPY GST INCLUDED June 25, 2021 Vol. 95 No. 21 Agreement # 40011922 PROUDLY SERVING MELVILLE AND SURROUNDING AREA SINCE 1929 • WWW.GRASSLANDSNEWS.CA • 1-306-728-5448 National gold for Melville student welder By Emily Jane Fulford Grasslands News This year’s Skills Can- ada National competition came close to home this year, in fact, close to many people. The 2021 event was held nationwide by means of virtual reality. In the past, the competi- tors would travel to take part in Quebec City but this year, the venue was switched to an online for- mat due to COVID-19. So when competitors took to the virtual stage, they were all playing on home turf, including Melville’s own, Kyan Ell. If the name of this Melville Comprehensive School (MCS) student seems familiar, it may be because he was rec- ognized earlier this year after winning gold in the welding category at the provincial level. On May 28th he did it again, this time winning gold for Sas- katchewan on Canada’s skill stage with a nation- wide audience. For Kyan, DENNIS MUZYKA | GRASSLANDS NEWS it’s not as much about Welding gold winning as it is about the .\DQ(OOKDVEHHQRQDZHOGLQJZLQQLQJVWUHDNDWWKH&DQDGD6NLOOV&RPSHWLWLRQVÀUVWWDNLQJKRPHJROGLQWKHSURYLQFLDODQGWKHQ trade he has a passion for. on June 15th he was announced as the gold medalist for the national competition. “I love welding be- cause the fact of build- thought it was so cool to strict guidelines for how not allowed to oversee the come up with a way to do ing stuff with metal, it’s do that and I would just the whole day would pro- competition process so a the event at all.