Drawing on Indigenous Legal Resources, 48 U.B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2015 Message from Chairperson William Irwin, Sc.D., CHP Hello All! This Is My First Newsbrief As Chair

Conference of Radiation Control Program Directors, Inc. NEWSBRIEF www.crcpd.org A Partnership Dedicated to Radiation Protection June 2015 Message from Chairperson William Irwin, Sc.D., CHP Hello All! This is my first Newsbrief as Chair. I want to start by thanking Mike Snee for sharing his thoughts and experiences with me this past year so I could be fully prepared now. I learned so much from Mike, and it was always a great experience when we were together. We are lucky to have people like Mike work with us. Second, I want to share with you how wonderful it is working with your Board of Directors. They conduct the business of the CRCPD with great skill and professionalism. It is routine for the Board and our colleagues in radiation protection - the FDA, NRC, EPA, DOE, FEMA, CDC, AAPM, ACR and ASTRO - to take on complex challenges, and find pathways to effective solutions. Acrnoymns in the Chairperson’s Message FDA - Food and Drug Administration CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NRC - Nuclear Regulatory Commission AAPM - American Association of Physicists in Medicine EPA - Environment Protection Agency ACR - American College of Radiology DOE - Department of Energy ASTRO - American Society for Radiation Oncology FEMA - Federal Emergency Management Agency g Inside Message from Chairperson...................................1 Call for Nominations Villforth Annual Lecture...........................................22 Greetings from Your Executive Director...................3 25th National Radon Training Conference National Conference -

Smgscmnim Har»Ld\.Comptpn' of Suburban.' Rangeg D by Dawson

-••'• '•" "•• —^r'* **" '''''' '"'''"' ;V|-'' '' ' ' -^ •—^- •'-'.' .'.'—- '• —!""'"'' ,J.-*Lu~.^L i '•' ' 'n •-' •- '"'ri'i'ir" '^M'^- •'""-'•'•'*'• " ' ' ' '••'••' mi i.i'n.. '•rutnlajr ''" ' ;'i'.|i —J-~. ,»'. *>- "' •'•'- • •. • • * •' 0- •• • >v.....•'''•'' THE' CRANFORD Cl'l'lZKN AND CHRONICLE, THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 1954 „_„*•' ' f .-'••/ Army last April and completed") it was announced this Ore ensemble singing two selec- v ' • basic training ot 'Camp*' Breckxn- tions, ~~ Scout Wins Citation Cranford, Garwood T(, £•,•''>.?' ridge, Ky. - ,, •-.,< .^ Prindpalls. i»=the firmvare Anne's Albert and Artn^-Meurer, and pur- y groups will be Joyce Skgggs, . ' ' " | !f • • -. ' |friMt&-iihHeart^^v«^ f' tl e business is the sales WiUiam Canteen Dances Planned Jacobsen. Jean Belden,- Susan Maher, eighth grade Cranfqrd wasUwong j l Tjnioa and service of, domestic water soft- Laird-and Carole Smith. James •student at Sittj Michael's School, re- County communjjte^hich-ibppa 8 For Local Young People ceived a heroism citation recently Lenney of the musk; faculty will their quotas In tfie annual i^, GAR\yoppj— A teen-age can- also play several, accompaniments from Union Council, Boy Scouts of iiineiabfe on the. organ. •; America.- - raising drive of the Union Com,,. * Church Cagers Defeat teen dance will be -''sponsored fTC Proceeds f/om this concert past winter, he res- Heart Association. Untj seventh and eighth grade students Central Railroad cf-New Jerseyj go tow-artf the' Organ Fund;,. cued an eight-year-old boy from Cranford's goal was $2 IM .» has- bten authorized by the Public 8 Fire Department Teams by the Recreation Commission ""btT-j Hammond -organ was purchased the -Rahway River. He is a mem- and $3,418 Wgs raised. -

BANDES DESSINÉES VENDREDI 20 NOVEMBRE 2009 À 17H30 Lots N° 1 À 249

MAISON DE VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES – AGRÉMENT N° 2001-005 7, Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées – 75008 Paris Tél. : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 20 – Fax : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 21 ÉRIC LEROY DANIEL PEREZ www.artcurial.com – [email protected] PARIS - HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT VENDREDI 20 ET SAMEDI 21 NOVEMBRE 2009 BANDES DESSINÉES VENDREDI 20 NOVEMBRE 2009 À 17H30 Lots n° 1 à 249 SAMEDI 21 NOVEMBRE 2009 À 11H Lots n° 250 à 486 SAMEDI 21 NOVEMBRE 2009 À 14H Lots n° 487 à 1139 PARIS - HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT PARIS - HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT 7, Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées, 75008 Paris Téléphones pendant l’exposition : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 17 +33 (0)1 42 99 20 11 Fax : +33 (0)1 42 99 16 45 COMMISSAIRE PRISEUR : François Tajan EXPERT : Bandes dessinées Éric Leroy, +33 (0)1 42 99 20 17 [email protected] ORDRE D’ACHAT, ENCHÈRES PAR TÉLÉPHONE : Marianne Balse, +33 (0)1 42 99 20 51 Fax : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 60 [email protected] COMPTABILITÉ ACHETEURS : Nicole Frèrejean, +33 (0)1 42 99 20 45 [email protected] COMPTABILITÉ VENDEURS : Sandrine Abdelli, +33 (0)1 42 99 20 06 [email protected] EXPOSITION À BRUXELLES : EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES : Une sélection des pièces présentées dans ce catalogue Mardi 17 Novembre de 11h à 19h sera exposée à Bruxelles, chez ABN AMRO, rue de la Mercredi 18 Novembre de 11h à 19h Chancellerie, 17A. Jeudi 19 Novembre de 11h à 19h Vendredi 13 novembre de 10 à 18 heures Vendredi 20 Novembre de 11h à 14h Samedi 14 novembre de 10 à 16 heures et sur rendez-vous avec l’expert VENTE Vendredi 20 Novembre à 17h30 Samedi 21 Novembre à 11h et 14h CATALOGUE -

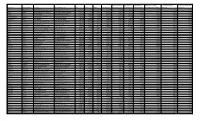

Last Name First Name Mi Job Title Department Name Base

MEDICAL, DENTAL PERS DISTRICT PERS EMPLOYEE PAYMENTS TO OTHER LTD, LIFE INSURANCE, ADDITIONAL MONETARY LAST NAME FIRST NAME MI JOB TITLE DEPARTMENT NAME BASE OT PAY OTHER GROSS PAY 2015 AND VISION COSTS CONTRIBUTION REIMBURSEMENT RETIREMENT PLAN (MPPP) MEDICARE COSTS (STD) Abao Roberto G Utility Worker Concord Shop & Inspection 30758.65 742.65 6023.96 37525.26 17248.98 4377.74 1632.63 2107.49 328.44 252.00 Abay Aron W Train Control Electronic Tech Train Control 62106.45 2357.59 6253.87 70717.91 23256.93 9399.66 1079.69 2425.15 2743.95 504.00 Abbott Robert District Right of Way Surveyor Real Estate & Property Develop 33615.36 52.52 125.00 33792.88 10181.53 4970.72 1680.80 2237.69 1383.77 168.00 Abdoun Hany I Sr Police Officer Police Operations Division 100413.68 52232.85 14428.78 167075.31 8928.24 51740.61 9670.02 1868.65 5488.89 0.00 Abdullah-Lewis Gloria D Principal Contract Specialist Contract Management Admin 109596.64 6887.02 3278.38 119762.04 29646.57 15457.05 5984.60 3529.22 4927.56 504.00 Abeygoonesekera Lakmin V Train Operator L-Line Rail Operations 3403.87 0.00 1000.00 4403.87 30090.57 0.00 0.00 275.98 877.62 504.00 Abplanalp Eric A Train Operator L-Line Rail Operations 69227.64 21678.32 4476.70 95382.66 12116.59 9786.60 3483.98 2443.19 3544.14 504.00 Abraha Alemnhe H Transit Vehicle Electronic Tec Richmond Shop & Inspection 80715.92 34761.17 8871.00 124348.09 9488.26 12001.73 4271.45 2704.99 4453.74 504.00 Acma Dennis A Operations Supv-Ops Liaison Civil Eng/Safety Monitor 93113.71 10978.55 12979.15 117071.41 30090.57 14268.69 -

R Fonds Fonds Documentaire Au 19 Novembre 2018 TITRE AUTEUR EDITEUR CATEGORIE 10 Contes De Chevaliers Et De Princesses Gudule Et

R_Fonds Fonds documentaire au 19 novembre 2018 TITRE AUTEUR EDITEUR CATEGORIE 10 contes de chevaliers et de princesses Gudule et Princesse Camcam Editions Lito Contes et légendes 10 minutes pour la planète Anne Tardy France Loisirs Art de vivre 10 petits chiens Collectif Gründ Premier âge 10 petits dauphins Collectif Gründ Premiers documentaires 100 activités d'éveil Montessori Eve Herrmann Nathan Art de vivre 100 infos à connaître : L'archéologie Collectif Piccolia Histoire 100 infos à connaître : Le climat Collectif Piccolia Sciences - Nature 100 infos à connaître : Les découvertes Collectif Piccolia Sciences - Nature 100 infos à connaître : Les fossiles Collectif Piccolia Sciences - Nature 100 infos à connaître : Les gladiateurs Collectif Piccolia Histoire 100 infos à connaître : Les merveilles du monde Collectif Piccolia Histoire 100 infos à connaître : Les volcans Collectif Piccolia Sciences - Nature 100 infos à connaître : Sauvons la terre Collectif Piccolia Sciences - Nature 1001 pattes Collectif Club du livre Hors catégorie 1001 pattes Collectif France Loisirs Album 101 fables du monde entier Corinne Albaut France Loisirs Contes et légendes 101 Trucs et Conseils Votre Chien Collectif Editions Fontaine Hors catégorie 101 trucs pour vaincre l'insomnie Josette Lyon Hachette Hors catégorie 13 histoires maboules de Noël et de rennes qui s'emmêlent ! Claire Renaud - Vincent Villeminot Fleurus Album 14 - 14 Silène Edgar et Paul Beorn Castelmore Roman dès 12 ans 1492 Jacques Attali Fayard Histoire - Politique 1492 - Christophe Colomb -

Starfleet Universe Ship Name Index

STARFLEET UNIVERSE SHIP NAME INDEX 0- Newly-added names (not sorted) attacked by a space dragon. • Converted to E4D 00 Spaceholder for newly added names. • Y178 participated in raid on Annox V SH104. A Adjudication: LDR SC. Abdul Gafur: Federation DWL. (Named for revolutionary • Y168 Converted to CWS. leader from Arakan-Burma). Adjutant: LDR MP Escort. Abolition: Lyran DD, Silver Moon County. Admirable: ISC DD-31. Abolition: Lyran DWX. Admiral Decius: Romulan FireHawk-X. Abomination: Klingon D6-26. Admiral Kang: Klingon C8-2. Received K-refit. • Y148, took part in raid to capture a Tholian ship, Escape • Y173 Fought Federation SL308. From the Holdfast, SL109-SL110. • Y174 damaged in battle with Federation carrier group Abundant Meadow of Grain: Seltorian FCR, Milky Way. SH70. Later that year, went into Kzinti space to negotiate • Y185 Destroyed SL259 by fighters from Tholian DNS treaty and barely escaped T3. Guardian while support for ACS Wind of Ordained • Y176, Led Klingon northern offensive SL261. Retribution. Admiral Kruge: Klingon C9A Stasis Dreadnought. Acclamation: ISC CC-03. • Y175 froze Federation ships SH81. Accolon: Rovillian warp-driven heavy cruiser Admiral Marcus: Romulan FireHawk-X. Aces and Eights: Orion CR, Dragon Cartel. Admiral Tacitus: Romulan FireHawk-X. •Y178 fought Federation CB at gas giant SL161. Admiral Tama: Romulan FHX. Aceveda: Federation POL, • Y195 defended Starbase Sanguinax from Andromedan • Y166 destroyed during encounter the first Andromedan, assault. SL212, First Encounter, CL#25. Admiral Tiercellus: Romulan FireHawk-X. • Y173, fought pirates SL324. Admire: ISC early destroyer Acheron: Romulan War Eagle. Adroit: Hydran DDE-002. • Y164 Raided a Gorn planet (SL278). Adroit: ISC MS-03. -

Mughal Period Costume

MUGHAL PERIOD COSTUME 1 The Mughal period is called the “golden period of Indian History”. Along with them they bought their culture, religion and customs which influenced the costumes and jewellary of that period. The Mughal inspired tailored salwar kameez became popular. Skilled masters and workmen were brought from other countries to make dresses. In the 16th century, during Akbar’s reign, the dresses consisted of knee length coat with a full skirt. Noorjahan, the wife of Jahangir, was the inventor of brocade. Noorjahan ushered in the cottage industry, and got her clothes made in chikenkari. Textile industry blossomed under the Mughal patronage. MATERIAL USED A variety of material were used during mughal period ranging from fine muslin to heavy brocades. Silk was the most common material used for the king’s dress. Nets were used for the veils. Golds and silver threads were also used. DESIGNS AND MOTIFS Persian influence dominated pattern was the paisley. It was used for corners design, overall decoration and borders. Mughal Costume • The ladies and gents of the Mughal empire wore beautiful and expensive clothes made from the finest materials and adorned themselves with jewellery from head to toe. • The garments of Mughal ladies were made of the finest muslins, silks, velvets and brocades. • The muslins used for their clothes were of three types: Ab-e- Rawan (running water), Baft Hawa (woven air) and Shabnam (evening dew). • Muslins called Shabnam were brought from Dacca and were famous as Dhaka malmal. Mughal Men's Clothing: • The Jama: The Yaktahi Jama (an unlined Jama) originated in Persia and Central Asia, where it was worn both short and long, over a pai-jama to form an outfit known as the "Bast Agag". -

Powell St. BART Station Modernization Program FINAL REPORT

September 2015 Powell St. BART Station Modernization Program FINAL REPORT Acknowledgements The Plan involved a larger number of BART internal stakeholders, San Francisco city agencies, and community stakeholders, including: BART City of San Francisco Agencies Community Stakeholders BART Board of Directors San Francisco Mayor’s Office Union Square Business Improvement District Tom Radoluvich Gillian Gillett Claude Imbault BART Administration and San Francisco Municipal Karin Flood Budget Transportation Agency Tenderloin Community Business District Bob Franklin Albert Hoe Dina Hilliard Britt Tanner Yerba Buena Business Improvement District BART Planning, Development Erin Miller and Construction Kim Walton Andrew Robinson Abigail Thorne-Lyman Kathleen Phu San Francisco Travel Alice Hewitt Mari Hunter Erin Gaenslen Bob Mitroff Peter Albert Jon Ballesteros Dennis Ho Shana Hurley Paul Frentsos Joe Lipkos John Rennels San Francisco Department of Planning Hotel Council of San Francisco Neil Hrushowy Norman Wong Jessica Lum Paul Voix Nick Perry Hilton San Francisco Shirley Ng San Francisco Office of Economic Tian Feng Michael Dunne and Workforce Development Tim Kempf Hotel Nikko San Francisco Val Menotti Ellyn Parker Louie Shapiro Lisa Pagan BART Operations Parc 55 Hotel Anthony Seung San Francisco Public Works Balvir Thind Eleanor Tang Eddie Cuevas Barney Smits Jerry Sanguinti Flood Building/Wilson Meany Carlton “Don” Allen Julia Lave Sheila Marko Cristiana Lippert Kelli Rudnick Dean Giebelhausen Nick Elsner Westfield Eric Fok Simon Bertrang Michael -

THE UNIVMITY of SHEFFIEM Vol=E One Jack L-Scott

THE UNIVMITY OF SHEFFIEM Department of Music The Evolution of the Brass Band and its Repertoire in Northern England Vol=e One Thesis presented for the degree of Ph. D. Jack L-Scott 1970 t(I Acknowledgments IV The time spent in research on this project has been invaluably enriched by the willing assistance of so many. I am grateful for the opportunity of being able to examine the instrument and music collections of the Sheffield., York Castlep Keighley,, Cyfarthfa and East Yorkshire Regimental museums. Acknowledgment is also given for the assistance received from the Sheffield Central Library (commerce and science and local history departments), Eanchester Central Librarys and espec- ially for the British Museum Reading Room and the University of Sheffield Main Library staff. From a practical point, acknowledgment is given to Boosey and Hawkes for a generous research grant as well as an extended personal tour of their facilities and to the University of S%effield research fund. Visits to 'Wright and Round, publishers of brass band music, have also been rewarding. Active partici- pation with the Stocksbridgep Sheffield Recreation and Staveley Works brass'bands has also proved valuable as well as the associ- ation with mmerous other bands,, notably Stalybridges and countless bandsmen. Finallys appreciation is expressed to the faculty, staff and students of the music department. The loss of Dr. Phillip Lord was a personal loss; the guidance of Professor Deane has been an inspiration. To my vifep Jan. and the childrenp go my special thanks for their patience and understanding. Jack L. Scott Sunmar7 vil The initial English amateur wind bands were reed bands which developed from the numerous military and militia bands prevalent during the beginning of the nineteenth century. -

Basic Radiation Safety Manual

Basic Radiation Safety Manual General License Ronan Engineering 8050 Production Drive Florence, KY 41042 P: 859-342-8500 F: 859-342-6426 www.ronanmeasure.com RONAN ENGINEERING COMPANY – MEASUREMENTS DIVISION 8050 Production Drive Florence KY 41042 Phone: (859) 342‐8500 Fax: (859) 342‐6426 Website: www.ronan.com E‐mail: [email protected] Ronan Engineering Radiation Safety Manual General License – GEN LIC General Licenses / Agreement States General licenses are issued within the body of the federal regulations that govern the possession and use of radioactive materials. The general license to own byproduct material installed in approved industrial gauging devices can be found in Title 10 Part 31.5 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Owners of these types of devices are legally responsible for the radioactive materials installed in the gage, and possess these materials under the auspices of their general license, which is issued to them in Title 10 Part 31.5. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (US NRC) is the federal entity that has been assigned the task of governing the possession and use of radioactive materials in the United States and its territories. Certain states have entered into an agreement with the NRC whereby the individual state governs the use of radioactive materials within its borders. These “Agreement States” have their own radiological agencies and their own sets of regulations pertaining to the use of radioactive materials. Radioactive materials that are possessed and used within one of these Agreement States are subject to that state’s laws. Included in this manual is a copy of 10 CFR Part 31.5. -

Revista Del Museo De La Plata''> , 1

RAPPORT PRELIMINAIRE SUR MON EXPÉDITION GÉOLOGIQUE UANS LA CORDILLÉRE ARGENTINO-CHILIENNE DU 40" ET 41" LATITUDE SUD REGIÓN DU N AH U E L-H U API ) V A l< D" LEO WEHRLI GÉOLOGUE DE LA SECTION D 'eXPLORATIONS NATIONALES AU MUSÉE DE LA PLATA AVEG PLANCHE Tomo IX I 7 RAPPORT PRELIMIN AIRE SUR MON EXPÉDITION GÉOLOGIQUE DANS LA CORDILLÉRE ARGENTIf^O-CHILIENNE DU 40° ET 41° LATITÜDE SUD (REGIÓN DU NAHUEL- HUAPI ) PAR Dr. LEO WEHRLI GÉOLOGUE DE LA SECTION d'exPLORATIONS NATIONALES AU MUbÉE DE LA PLATA [. DESCRIPTION CHRONOLOGIQUE DU VOYAGE I . Départ pour Puerto Montt Notre zone d'exploration étant fixée pour cette campagne aux 40" et 4i°latitude sud de la Cordillére argentino -chilienne, nous quittámes La Plata, le 24 novembre 1897, pour passer au Chüi par Mendoza et Uspallata et commencer nos travaux par Textrémité ouest du cóté du Pacifique. A Mendoza, les fameuses institutions du chemin de fer Trasandino, que nous connaissions déjá depuis l'expédition de i'année derniére, nous ont retenus jusqu'au matin du i"'' décembre. C'est ainsi que jai eu le temps de visiter la región du charbon mediocre de Challao. Le 2 décembre, au soir, nous atteignimes Santiago avec Tintention de nous embarquer aussitót á Valparaíso pour Puerto Montt, port de la cote sud du Chüi, qui était designé comme point de départ pour notre expédition. A Valparaíso, mon coilégue M. le Dr. Charles Burckhardt tomba ma- lade. Nous avions déjá entrepris ensemble Fexpédition de la saison pas- sée C) et ce n'est qu'avec le plus grand regret que je l'ai dü laisser á Valparaíso, oú íl resta jusqu'au mois de févríer. -

Co Orru Uptio on in N Kr Rypt Tgar Rden N

Corruption in Kryptgarden Kryptgarden Forest has long been a place feared by travelers. Now, the Cult of the Dragon has used that fear to its advantage, securing a stronghold deep in the forest. The Harpers, Order of the Gauntlet, Emerald Enclave, Lords’ Alliance, and the Zhentarim are recruiting groups of adventurers to infiltrate the forest to find out the cult’s purpose. Join hundreds of others in this interactive play experience. A special adventure for 1st-4th level characters. Adventure Code: DDEP1‐1 Credits Adventure Design: Teos Abadia Development and Editing: Claire Hoffman, Chris Tulach, Travis Woodall D&D Organized Play: Chris Tulach D&D R&D Player Experience: Greg Bilsland D&D Adventurers League Wizards Team: Greg Bilsland, Chris Lindsay, Shelly Mazzanoble, Chris Tulach D&D Adventurers League Administrators: Robert Adducci, Bill Benham, Travis Woodall, Claire Hoffman, Greg Marks, Alan Patrick Debut: August 16, 2014 Limited Release DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, D&D Encounters, D&D Expeditions, D&D Epics, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and thheir respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2014 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA.