Unit 26 Population in Mughal India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Start of Arakanese Rule in Chittagong Around 1590 Was As We Saw Closely Connected with the Development of an Arakanese-Portuguese Partnership

Arakan and Bengal : the rise and decline of the Mrauk U kingdom (Burma) from the fifteenth to the seventeeth century AD Galen, S.E.A. van Citation Galen, S. E. A. van. (2008, March 13). Arakan and Bengal : the rise and decline of the Mrauk U kingdom (Burma) from the fifteenth to the seventeeth century AD. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12637 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12637 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER THREE THE RISE OF MRAUK U INFLUENCE (1593-1612) The start of Arakanese rule in Chittagong around 1590 was as we saw closely connected with the development of an Arakanese-Portuguese partnership. The account of Fernberger and the earlier involvement of the Portuguese mercenaries in the army of the Bengal sultans are testimony to the important role of these Portuguese communities in the Arakan-Bengal continuum. When Man Phalaung died in 1593 he was succeeded by his son king Man Raja- kri (1593-1612).1 Man Raja-kri would continue the expansion of Arakanese rule along the shores of the Bay of Bengal. In 1598 he would take part in the siege of Pegu that would lead to the end of the first Toungoo dynasty in Burma in 1599. The early years of the seventeenth century would also witness the first armed confrontations between the Arakanese and the Mughals in south-eastern Bengal. -

Mughal Warfare

1111 2 3 4 5111 Mughal Warfare 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3111 Mughal Warfare offers a much-needed new survey of the military history 4 of Mughal India during the age of imperial splendour from 1500 to 1700. 5 Jos Gommans looks at warfare as an integrated aspect of pre-colonial Indian 6 society. 7 Based on a vast range of primary sources from Europe and India, this 8 thorough study explores the wider geo-political, cultural and institutional 9 context of the Mughal military. Gommans also details practical and tech- 20111 nological aspects of combat, such as gunpowder technologies and the 1 animals used in battle. His comparative analysis throws new light on much- 2 contested theories of gunpowder empires and the spread of the military 3 revolution. 4 As the first original analysis of Mughal warfare for almost a century, this 5 will make essential reading for military specialists, students of military history 6 and general Asian history. 7 8 Jos Gommans teaches Indian history at the Kern Institute of Leiden 9 University in the Netherlands. His previous publications include The Rise 30111 of the Indo-Afghan Empire, 1710–1780 (1995) as well as numerous articles 1 on the medieval and early modern history of South Asia. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 40111 1 2 3 44111 1111 Warfare and History 2 General Editor 3 Jeremy Black 4 Professor of History, University of Exeter 5 6 Air Power in the Age of Total War The Soviet Military Experience 7 John Buckley Roger R. -

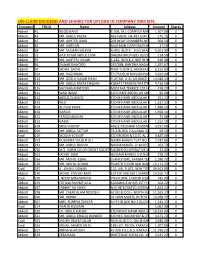

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Islam & Sufism

“There is no Deity except Allah; Mohammad (SM) (PBUH) is The Messenger of Allah” IN THE NAME OF ALLAH, MOST GRACIOUS & MOST MERCIFUL “The Almighty God Certainly HAS BEEN, IS and WILL CONTINUE to Send Infinite Love and Affection to His Beloved Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (SM) (PBUH) along with his Special Angels who are Directed by the Almighty God to Continuously Salute with Respect, Dignity and Honor to the Beloved Holy Prophet for His Kind Attention. The Almighty God again Commanding to the True Believers to Pay Respect with Dignity and Honor for Their Forgiveness and Mercy from the Beloved Holy Prophet of Islam and Mankind.” - (Al‐Quran Surah Al-Ahzab, 33:56) “Those who dies in the Path of Almighty God, Nobody shall have the doubt to think that they are dead but in fact they are NOT dead but Alive and very Close to Almighty, Even Their every needs even food are being sent by Almighty, but people among you will not understand.” - (Al‐Quran Surah Al-Imran 3:169) “Be Careful of the Friends of Almighty God, They do not worry about anything or anybody.” - (Al‐Quran, Surah Yunus 10:62) “Those who dies or pass away in the Path of Almighty God, nobody shall think about Them as They are dead, But people can not understand Them.” - (Al‐Quran, Surah Baqarah 2:154) Author: His Eminency Dr. Hazrat Sheikh Shah Sufi M N Alam (MA) 2 His Eminency Dr. Hazrat Sheikh Shah Sufi M N Alam’s Millennium Prophecy Statement Authentic History of The World Arrival of Imam Mahdi (PBUH) with Reemergence of Jesus Christ (A) To Co-Create Heaven on Earth Published by: Millennium Trade Link USA Corporation Library of Congress, Cataloging in Publication Data Copyright@ 2019 by His Eminency Dr. -

Chishti Sufis of Delhi in the LINEAGE of HAZRAT PIR-O-MURSHID INAYAT KHAN

Chishti Sufis of Delhi IN THE LINEAGE OF HAZRAT PIR-O-MURSHID INAYAT KHAN Compiled by Basira Beardsworth, with permission from: Pir Zia Inayat Khan A Pearl in Wine, The “Silsila-i Sufian”: From Khwaja Mu’in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani Sadia Dehlvi Sufism, The Heart of Islam, and The Sufi Courtyard, Dargahs of Delhi All the praise of your advancement in this line is due to our masters in the chain who are sending the vibrations of their joy, love, and peace. - Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, in a letter to Murshida Rabia Martin There is a Sufi tradition of visiting the tombs of saints called ziyarah (Arabic, “visit”) or haazri (Urdu, “attendance”) to give thanks and respect, to offer prayers and seek guidance, to open oneself to the blessing stream and seek deeper connection with the great Soul. In the Chishti lineage through Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, there are nine Pirs who are buried in Delhi, and many more whose lives were entwined with Delhi. I have compiled short biographies on these Pirs, and a few others, so that we may have a glimpse into their lives, as a doorway into “meeting” them in the eternal realm of the heart, insha’allah. With permission from the authors, to whom I am deeply grateful to for their work on this subject, I compiled this information primarily from three books: Pir Zia Inayat Khan, The “Silsila-i Sufian”: From Khwaja Mu’in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani, published in A Pearl in Wine Sadia Dehlvi, Sufism, The Heart of Islam, and The Sufi Courtyard, Dargahs of Delhi For those interested in further study, I highly recommend their books – I have taken only small excerpts from their material for use in this document. -

Gendered 'Landscape': Jahanara Begum's Patronage, Piety and Self

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation ―Gendered ‗Landscapes‘: Jahan Ara Begum‘s (1614-1681) Patronage, Piety and Self-Representation in 17th C Mughal India‖ Band 1 von 1 Verfasser Afshan Bokhari angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092315 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin/Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Ebba Koch TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page 0 Table of Contents 1-2 Curriculum Vitae 3-5 Acknowledgements 6-7 Abstract 8 List of Illustration 9-12 Introduction 13-24 Figures 313-358 Bibliography 359-372 Chapter One: 25-113 The Presence and Paradigm of The „Absent‟ Timurid-Mughal Female 1.1 Recent and Past Historiographies: Ruby Lal, Ignaz Goldziher, Leslie Pierce, Stephen Blake 1.2 Biographical Sketches: Timurid and Mughal Female Precedents: Domesticity and Politics 1.2.1 Timurid Women (14th-15th century) 1.2.2 Mughal Women (16th – 17th century) 1.2.3 Nur Jahan (1577-1645): A Prescient Feminist or Nemesis? 1.2.4 Jahan Ara Begum (1614-1681): Establishing Precedents and Political Propriety 1.2.5 The Body Politic: The Political and Commercial Negotiations of Jahan Ara‘s Well-Being 1.2.6 Imbuing the Poetic Landscape: Jahan Ara‘s Recovery 1.3 Conclusion Chapter Two: 114-191 „Visions‟ of Timurid Legacy: Jahan Ara Begum‟s Piety and „Self- Representation‟ 2.1 Risala-i-Sahibiyāh: Legacy-Building ‗Political‘ Piety and Sufi Realization 2.2 Galvanizing State to Household: Pietistic Imperatives Dynastic Legitimacy 2.3 Sufism, Its Gendered Dimensions and Jahan -

Vedic Religion Is Unclear

HISTORY UGC NET/SET/JRF (Paper II and III) Amitava Chatterjee Delhi Chennai No part of this eBook may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the publisher’s prior written consent. Copyright © 2014 Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd. This eBook may or may not include all assets that were part of the print version. The publisher reserves the right to remove any material in this eBook at any time. ISBN: 9789332520622 e-ISBN: 9789332537040 First Impression Head Office: 7th Floor, Knowledge Boulevard, A-8(A) Sector 62, Noida 201 309, India. Registered Office: 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India. In fond memories of Dada and Mamoni About the Author "NJUBWB$IBUUFSKFF faculty of history at Ramsaday College, Howrah and guest faculty at Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata is a Charles Wallace Fellow (UK, 2012). He has teaching experience of over 12 years. He has completed two UGC sponsored Minor Research Projects titled ‘Sports History in Bengal: A microcosmic study’ and ‘ Evolution of Women’s Sporting Culture in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Bengal.’ He has edited two books 1FPQMFBU-BSHF1PQVMBS$VMUVSFJO.PEFSO #FOHBMand1FPQMFBU1MBZ4QPSU $VMUVSFBOE/BUJPOBMJTNandwritten extensively in reputed national and international journals such as 4PDDFS 4PDJFUZ(Routledge), 4QPSUJO4PDJFUZ Routledge)*OUFSOBUJPOBM+PVS OBMPG)JTUPSZPG4QPSU $BMDVUUB)JTUPSJDBM+PVSOBM+PVSOBMPG)JTUPSZ to name a few. He is also a guest editor of 4QPSUJO4PDJFUZand referee of 4PDDFS4PDJFUZ(Routledge). Some of his books include #IBSBU07JTIXBand *UJIBTFS"MPLF&VSPQFS3VQBOUBSpublished by Pearson Education. His area of interest is sports history and his thrust research area is the evolution of sporting culture in colonial Bengal. -

Fairs & Festivals, Part VII-B, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan

PRG. 172 B (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XIV .RAJASTHAN PART VII-B FAIRS & FESTIVALS c. S. GUPTA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan 1966 PREFACE Men are by their nature fond of festivals and as social beings they are also fond of congregating, gathe ring together and celebrating occasions jointly. Festivals thus culminate in fairs. Some fairs and festivals are mythological and are based on ancient traditional stories of gods and goddesses while others commemorate the memories of some illustrious pers<?ns of distinguished bravery or. persons with super-human powers who are now reverenced and idealised and who are mentioned in the folk lore, heroic verses, where their exploits are celebrated and in devotional songs sung in their praise. Fairs and festivals have always. been important parts of our social fabric and culture. While the orthodox celebrates all or most of them the common man usually cares only for the important ones. In the pages that follow an attempt is made to present notes on some selected fairs and festivals which are particularly of local importance and are characteristically Rajasthani in their character and content. Some matter which forms the appendices to this book will be found interesting. Lt. Col. Tod's fascinating account of the festivals of Mewar will take the reader to some one hundred fifty years ago. Reproductions of material printed in the old Gazetteers from time to time give an idea about the celebrations of various fairs and festivals in the erstwhile princely States. Sarva Sbri G. -

2 - STAR BADGE WINNERS 28Th IKMC - 2018

2 - STAR BADGE WINNERS 28th IKMC - 2018 SR. NO. ROLL NO. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME CLASS 1 18-051-01440-1-014-M AADHEEN AHMED NAVEED ALI 1 2 18-021-02079-1-054-M AAMISH SIDDIQUI AAMIR SIDDIQUI 1 3 18-021-02014-1-010-M AAMNA KASHIF JADA MUHAMMAD KASHIF JADA 1 4 18-51-02051-1-005-M AAMNA USMAN USMAN IJAZ 1 5 18-021-02014-1-012-M AAMNA YOUNUS FAROOQ YOUNUS FAROOQ 1 6 18-021-02079-1-010-M AAYAN IKHLAS IKHLAS AHMED 1 7 18-42-01222-1-006-M AAYAN QASIM BHATTI QASIM ISHAQUE BHATTI 1 8 18-42-01030-1-008-M AAYMA TALAL SHAIKH TALAL HUSSAIN SHAIKH 1 9 18-55-01197-1-026-M AAZAN AHMAD CH. MOHAMMAD ARSHAD 1 10 18-022-02340-1-003-M AAZAN ALI MANGRIO IMRAN ALI MANGRIO 1 11 18-021-02244-1-033-M ABAAN SOHAIL MUHAMMAD HAFIZ SOHAIL 1 12 18-42-01293-1-049-M ABBISH AWAIS KHURRAM IKRAM 1 13 18-021-02079-1-006-M ABDAL KHAN QAYAMUDDIN QAYAMUDDIN 1 14 18-021-01544-1-233-M ABDUL RAFAY 1 15 18-051-01597-1-004-M ABDUL AHAD MUHAMMAD HAMID 1 16 18-021-01544-1-211-M ABDUL AHAD IMRAN IMRAN KHATRI 1 17 18-021-01544-1-131-M ABDUL AHAD KASHIF KASHIF JAHANGIR 1 18 18-66-01471-1-001-M ABDUL BARI TALHA UMER 1 19 18-53-01194-1-009-M ABDUL BASIT GHAZANFER IQBAL 1 20 18-41-01024-1-009-M ABDUL DYIM MUHAMMAD ASIF 1 21 18-021-01855-1-034-M ABDUL HADI ABDUL MAJEED 1 22 18-42-01244-1-002-M ABDUL HADI MUHAMMAD QASIM 1 23 18-546-02255-1-002-M ABDUL HADI KAMAL AHMED 1 24 18-547-01480-1-006-M ABDUL HADI TARIQ 1 ___________________________________________________________________________ Note: 55% or above but less than 70% score achieved in the respective class 2 - STAR BADGE WINNERS 28th IKMC - 2018 SR. -

Mughal River Forts in Bangladesh (1575-1688)

MUGHAL RIVER FORTS IN BANGLADESH (1575-1688) AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL by Kamrun Nessa Khondker A Thesis Submitted to Cardiff University in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy SCHOOL OF HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY AND RELIGION CARDIFF UNIVERSITY DECEMBER 2012 1 | P a g e DECLARATION AND STATEMENTS DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed …………………………… (Candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of M.Phil. Signed …………………………… (Candidate) Date …………………………. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………… (Candidate) Date………………………….. STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………… (Candidate) Date………………………… 2 | P a g e ABSTRACT The existing scholarship on the Mughal river forts fails to address some key issues, such as their date of construction, their purpose, and the nature of their construction, how they relate to Mughal military strategy, the effect of changes in the course and river systems on them, and their role in ensuring the defence of Dhaka. While consultation of contemporary sources is called for to reflect upon these key issues, it tends to be under- used by modern historians. -

India from 16Th Century to Mid-18Th Century

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology India from 16th Century to Mid 18th Century Subject: INDIA FROM 16TH CENTURY TO MID 18TH CENTURY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS India in the 16th Century The Trading World of Asia and the Coming of the Portuguese, Polity and Economy in Deccan and South India, Polity and Economy in North India, Political Formations in Central and West Asia Mughal Empire: Polity and Regional Powers Relations with Central Asia and Persia, Expansion and Consolidation: 1556-1707, Growth of Mughal Empire: 1526-1556, The Deccan States and the Mughals, Rise of the Marathas in the 17th Century, Rajput States, Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golkonda Political Ideas and Institutions Mughal Administration: Mansab and Jagir, Mughal Administration: Central, Provincial and Local, Mughal Ruling Class, Mughal Theory of Sovereignty State and Economy Mughal Land Revenue System, Agrarian Relations: Mughal India, Land Revenue System: Maratha, Deccan and South India, Agrarian Relations: Deccan and South India, Fiscal and Monetary System, Prices Production and Trade The European Trading Companies, Personnel of Trade and Commercial Practices, Inland and Foreign Trade Non-Agricultural Production, Agricultural Production Society and Culture Population in Mughal India, Rural Classes and Life-style, Urbanization, Urban Classes and Life-style Religious Ideas and Movements, State and Religion, Painting and Fine Arts, Architecture, Science and Technology, Indian Languages and Literature India at the Mid 18th Century Potentialities of Economic Growth: An Overview, Rise of Regional Powers, Decline of the Mughal Empire Suggested Readings 1. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/27/2021 04:41:18AM Via Free Access 162 Part II: Restraint and Excess

Mughal military violence in South Asia 9 ‘The wrath of God’: legitimization and limits of Mughal military violence in early modern South Asia Pratyay Nath In 1568, an army under the command of the third Mughal emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar (r. 1556–1605) stormed the fort of Chitor in western India after a prolonged siege of six months. On the day of the victory, Akbar ordered a general massacre (qat..l-i ‘āmm) of the garrison as well as of the general population. According to contemporary texts, some 30,000 people were killed as a result. This event stands out as one of the most glaring instances of spectacular military violence in Mughal history, where not only the combatants but also a very large number of civilians were put to the sword. Abul Fazl, the principal biographer of Akbar, pro- vides an official justification of this drastic action. He writes that in the final hours of the defence of the fort, a garrison of around 8,000 men received active assistance from around 40,000 peasants. He points out that when Alauddin, the Khalji sultan of Delhi, had conquered Chitor in the early fourteenth century, ‘the peasantry were not put to death as they had not engaged in fighting’.1 Abul Fazl argues that on the present occasion, they had to be punished because of the ‘great zeal and activity’ they had shown in defending the fort against the Mughal army.2 Was this incident just a plain act of revenge against an adversary that had offered dogged resistance against imperial expansion? What does this massacre tell us about the larger history of how the empire justified similar acts of military vio- lence? Was the way Abul Fazl legitimized the massacre of the civilian population of Chitor different from how instances of violence against actual combatants were legitimized? What sorts of limits to military violence did Mughal imperial ideology prescribe and Mughal armies observe? In order to answer these questions, one must begin by understanding how Mughal imperial culture conceptualized sovereignty, kingly rule, and war.