Review of Higgins, Anglo-Saxon Community in J.R.R. Tolkien's The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf

Merge Volume 1 Article 2 2017 The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Tera Pate Follow this and additional works at: https://athenacommons.muw.edu/merge Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Tara. "The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf." Merge, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 1-17. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ATHENA COMMONS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Merge by an authorized editor of ATHENA COMMONS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Image Source: “Converged” by Phil Whitehouse is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Volume 1 Spring 2017 Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1 Spring, 2017 Managing Editor: Maddy Norgard Editors: Colin Damms Cassidy DeGreen Gabrielle Lestrade Faculty Advisor: Dr. Kim Whitehead Faculty Referees: Dr. Lisa Bailey Dr. April Coleman Dr. Nora Corrigan Dr. Jeffrey Courtright Dr. Sacha Dawkins Dr. Randell Foxworth Dr. Amber Handy Dr. Ghanshyam Heda Dr. Andrew Luccassan Dr. Bridget Pieschel Dr. Barry Smith Mr. Alex Stelioes – Wills Pate 1 Tera Katherine Pate The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Old English literature is the product of a country in religious flux. Beowulf and its women are creations of this religiously transformative time, and juxtapositions of this work’s women with the women of more Pagan and, alternatively, more Christian works reveals exactly how the roles of women were transforming alongside the shifting of religious belief. -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

The Mead-Hall Community

Journal of Medieval History 37 (2011) 19–33 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Medieval History journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ jmedhist The mead-hall community Stephen Pollington* 46 Beeleigh East, Fryerns, Basildon, Essex, SS14 2RR, UK abstract Keywords: Mead-hall The paper provides background context to the Anglo-Saxon concept Feasting of the ‘mead-hall’, the role of conspicuous consumption in early Gift giving medieval society and the use of commensality to strengthen hori- Ritual zontal and vertical social bonds. Taking as its primary starting point Anglo-Saxon England the evidence of the Old English verse tradition, supported by linguistic and archaeological evidence and contemporary compar- ative material, the paper draws together contemporaneous and modern insights into the nature of feasting as a social medium. The roles of the ‘lord’ and ‘lady’ as community leaders are examined, with particular regard to their position at the epicentre of radiating social relationships. Finally, the inverse importance of the mead- hall as a declining social institution and a developing literary construct is addressed. Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. The term ‘mead-hall’ is no longer current among English-speakers; it is used here as a shorthand notation for the Germanic customs and observances surrounding the consumption and distribution of food and drink in a ceremonial setting, the giving and receiving of honorifics and rewards, and the establishment of a communal identity expressed through formal relationships to a pair of individuals whom we may call the ‘lord’ and ‘lady’. It further relates to a set of traditions concerning hospitality offered to strangers, informal entertainment and the maintenance of wider social relationships. -

13 Reflections on Tolkien's Use of Beowulf

13 Reflections on Tolkien’s Use of Beowulf Arne Zettersten University of Copenhagen Beowulf, the famous Anglo-Saxon heroic poem, and The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Author of the Century”, 1 have been thor- oughly analysed and compared by a variety of scholars.2 It seems most appropriate to discuss similar aspects of The Lord of the Rings in a Festschrift presented to Nils-Lennart Johannesson with a view to his own commentaries on the language of Tolkien’s fiction. The immediate pur- pose of this article is not to present a problem-solving essay but instead to explain how close I was to Tolkien’s own research and his activities in Oxford during the last thirteen years of his life. As the article unfolds, we realise more and more that Beowulf meant a great deal to Tolkien, cul- minating in Christopher Tolkien’s unexpected edition of the translation of Beowulf, completed by J.R.R. Tolkien as early as 1926. Beowulf has always been respected in its position as the oldest Germanic heroic poem.3 I myself accept the conclusion that the poem came into existence around 720–730 A.D. in spite of the fact that there is still considerable debate over the dating. The only preserved copy (British Library MS. Cotton Vitellius A.15) was most probably com- pleted at the beginning of the eleventh century. 1 See Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, 2000. 2 See Shippey, T.A., The Road to Middle-earth, 1982, Pearce, Joseph, Tolkien. -

Beowulf: God, Men, and Monster

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 10 Article 1 2010 Beowulf: God, Men, and Monster Emily Bartz Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Bartz, Emily (2010) "Beowulf: God, Men, and Monster," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 10 , Article 1. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol10/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Bartz: Beowulf: God, Men, and Monster Emily Bartz Beowulf: God, Men, and Monsters The central conflict of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf is the struggle between the decentralising and supernatural ways of the ancients (Shield Sheafson, Grendel, and Grendel‟s Mother) and the centralising and corporeal values of the modern heroes (Hrothgar, Beowulf, and Wiglaf.) The poet traces a definitive move away from the ancient‟s pagan heroic values to his own Christian heroic values. However, as in the poet‟s contemporary culture, certain pagan traditions, such as familial fidelity, persist in Beowulf due to their compatibility with Christian culture. The poet‟s audience, the Anglo-Saxons, honoured their pagan ancestors through story telling. The Christian leadership discouraged story telling since the Anglo-Saxons‟ ancestors were pagans and thus beyond salvation. -

Beowulf's Arrival

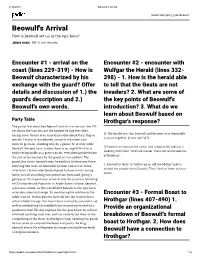

2/16/2018 Beowulf's Arrival padlet.com/jenny_ryan/beowulf Beowulf's Arrival How is Beowulf set up as the epic hero? JENNY RYAN FEB 15, 2018 09:30AM Encounter #1 - arrival on the Encounter #2 - encounter with coast (lines 229-319) - How is Wulfgar the Herald (lines 332- Beowulf characterized by his 398) - 1. How is the herald able exchange with the guard? Offer to tell that the Geats are not details and discussion of 1.) the invaders? 2. What are some of guard's description and 2.) the key points of Beowulf's Beowulf's own words. introduction? 3. What do we learn about Beowulf based on Party Table Hrothgar's response? The guard rst describes Beowulf and his warriors on line 247. He claims the warriors are the boldest he had ever seen, 1) The herald saw that Beowulf and his men were honorable having never before seen armed men disembark their ship so and put together. (Lines 342-347). quickly. He also is immediately aware of the noble aura Beowulf gives off, claiming only by a glance he is truly noble. 2) Beowulf announces his name, and respectfully asks for a Beowulf, the epic hero, is described as so mighty that he is meeting with their “lord and master, the most renowned son easily recognizable as a great warrior, even distinguished from of Halfdane”. the rest of his warriors by the guard as true nobility. The guard also trusts Beowulf after he explains his business there, 3. Beowulf is there to “follow up an old friendship” and to believing him to be an honorable person who is true in his defend the people from Grendel. -

Beowulf Was Not There”: Compositional Implications of Beowulf, Lines 1299B-1301

Oral Tradition, 4/3 (1989): 316-329 “Beowulf Was Not There”: Compositional Implications of Beowulf, Lines 1299b-1301 Michael D. Cherniss During the second night of Beowulf’s stay in Denmark, Grendel’s mother, seeking revenge for her son’s death, enters Heorot. When the warriors in the hall discover her presence, she takes fl ight, but on her way out she seizes and kills an unnamed warrior who, the poet says, was especially dear to his lord, Hrothgar. At this point in the narrative the poet tells us something we did not previously know (1299b-1301): Næs Beowulf ðær, ac wæs oþer in ær geteohhod æfter maþðumgife mærum Geate.1 [Beowulf was not there, but rather he was in another place, assigned earlier to the famous Geat after the giving of treasure.] Subsequently, the female monster completes her escape, leaving confusion and renewed suffering behind her. Although so far as I am aware the lines about Beowulf’s absence from Heorot during the second attack in two nights upon its sleeping inhabitants have elicited no previous commentary, they have for some time struck me as being somewhat curious. My discomfort has little or nothing to do with the narrative function of the information that the poet supplies here. Obviously, if Beowulf were present in Heorot the poem’s audience would expect him to challenge Grendel’s less powerful mother just as he had previously challenged her son and, if the results were the same, instead of an exciting battle in the monster’s lair, we would very likely have only a much less interesting reduplication of the earlier hand-to-hand struggle. -

Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2013 Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation VanDonkelaar, Ilse Schweitzer, "Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 216. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/216 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OLD ENGLISH ECOLOGIES: ENVIRONMENTAL READINGS OF ANGLO-SAXON TEXTS AND CULTURE by Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Western Michigan University December 2013 Doctoral Committee: Jana K. Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Eve Salisbury, Ph.D. Richard Utz, Ph.D. Sarah Hill, Ph.D. OLD ENGLISH ECOLOGIES: ENVIRONMENTAL READINGS OF ANGLO-SAXON TEXTS AND CULTURE Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2013 Conventionally, scholars have viewed representations of the natural world in Anglo-Saxon (Old English) literature as peripheral, static, or largely symbolic: a “backdrop” before which the events of human and divine history unfold. In “Old English Ecologies,” I apply the relatively new critical perspectives of ecocriticism and place- based study to the Anglo-Saxon canon to reveal the depth and changeability in these literary landscapes. -

The Ideal Study Guides for Today's Students! —30% Off

The ideal study guides for today’s students! — 30% off FollettBound editions— NO FEAR LITERATURE Beowulf for warfare and hatred that woke again. Chapter 1 With envy and anger an evil spirit endured the dole in his dark abode, EOWULF became the ruler of the Spear-Danes and was that he heard each day the din of revel Bbeloved by all. He had an heir, the great Halfdane, high in the hall: there harps rang out, whose wisdom and sturdiness guided and protected the clear song of the singer. He sang who knew people. Halfdane had three sons—Heorogar, Hrothgar, and tales of the early time of man, Halga—and a daughter, who married Onela and became how the Almighty made the earth, queen of the Swedes. Hrothgar was such a great warrior that fairest fields enfolded by water, men were eager to fight alongside him. His army grew large. set, triumphant, sun and moon He decided to build an enormous hall, the largest anyone for a light to lighten the land-dwellers, had ever seen. From there, he would rule and give everything and braided bright the breast of earth he could to his people, except for land and his men’s lives. with limbs and leaves, made life for all He brought in workmen from all over the world, and his of mortal beings that breathe and move. immense and noble hall was soon completed. He named it Heorot. Once inside, he kept his promise to give gifts and So lived the clansmen in cheer and revel treasure to his people. -

Grendel Thesis Actual

SHAPESHIFTER AND CHAMELEON: GRENDEL AS AN INDICATOR OF CULTURAL FEARS AND ANXIETIES An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by CHRISTINA OWENS Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. Britt Mize May 2016 Major: English TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................1 DEDICATION ...............................................................................................................................3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................................................................4 CHAPTER I THE PRE-9/11 GRENDEL ...................................................................................5 Introduction ...........................................................................................................7 Grendel during World War I ................................................................................12 Grendel during World War II ...............................................................................23 Illustrated translations .........................................................................................27 Potentially sympathetic moments ........................................................................31 II GARDNER’S GRENDEL ...................................................................................35 -

Mead-Halls of the Oiscingas: a New Kentish Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall Complex Phenomenon

Mead-halls of the Oiscingas: a new Kentish perspective on the Anglo-Saxon great hall complex phenomenon Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Thomas, G. (2018) Mead-halls of the Oiscingas: a new Kentish perspective on the Anglo-Saxon great hall complex phenomenon. Medieval Archaeology, 62 (2). pp. 262-303. ISSN 0076-6097 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76215/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 Publisher: Maney Publishing All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Medieval Archaeology ISSN: 0076-6097 (Print) 1745-817X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ymed20 Mead-Halls of the Oiscingas: A New Kentish Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall Complex Phenomenon GABOR THOMAS To cite this article: GABOR THOMAS (2018) Mead-Halls of the Oiscingas: A New Kentish Perspective on the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall Complex Phenomenon, Medieval Archaeology, 62:2, 262-303, DOI: 10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2018.1535386 © 2018 The Author(s). -

Grendel's Cave Help 14 April 2011 Version

Grendel’s Cave Help 14 April 2011 Version 2.2 Page 1 of 23 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................2 ABOUT GRENDEL’S CAVE ...........................................................................................................................3 STARTING OUT..............................................................................................................................................4 CREATING AN ACCOUNT ................................................................................................................................ 4 CREATING A THANE ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SELECTING A KINGDOM .................................................................................................................................. 5 PLAYING THE GAME .....................................................................................................................................6 NAVIGATION ................................................................................................................................................. 6 FACING ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 MODIFYING YOUR ACTIONS ...........................................................................................................................