Beowulf: God, Men, and Monster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf

Merge Volume 1 Article 2 2017 The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Tera Pate Follow this and additional works at: https://athenacommons.muw.edu/merge Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Tara. "The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf." Merge, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 1-17. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ATHENA COMMONS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Merge by an authorized editor of ATHENA COMMONS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Image Source: “Converged” by Phil Whitehouse is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Volume 1 Spring 2017 Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1 Spring, 2017 Managing Editor: Maddy Norgard Editors: Colin Damms Cassidy DeGreen Gabrielle Lestrade Faculty Advisor: Dr. Kim Whitehead Faculty Referees: Dr. Lisa Bailey Dr. April Coleman Dr. Nora Corrigan Dr. Jeffrey Courtright Dr. Sacha Dawkins Dr. Randell Foxworth Dr. Amber Handy Dr. Ghanshyam Heda Dr. Andrew Luccassan Dr. Bridget Pieschel Dr. Barry Smith Mr. Alex Stelioes – Wills Pate 1 Tera Katherine Pate The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Old English literature is the product of a country in religious flux. Beowulf and its women are creations of this religiously transformative time, and juxtapositions of this work’s women with the women of more Pagan and, alternatively, more Christian works reveals exactly how the roles of women were transforming alongside the shifting of religious belief. -

Widsith, Beowulf, Finnsburgh, Waldere, Deor. Done Into Common

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

The Mead-Hall Community

Journal of Medieval History 37 (2011) 19–33 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Medieval History journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ jmedhist The mead-hall community Stephen Pollington* 46 Beeleigh East, Fryerns, Basildon, Essex, SS14 2RR, UK abstract Keywords: Mead-hall The paper provides background context to the Anglo-Saxon concept Feasting of the ‘mead-hall’, the role of conspicuous consumption in early Gift giving medieval society and the use of commensality to strengthen hori- Ritual zontal and vertical social bonds. Taking as its primary starting point Anglo-Saxon England the evidence of the Old English verse tradition, supported by linguistic and archaeological evidence and contemporary compar- ative material, the paper draws together contemporaneous and modern insights into the nature of feasting as a social medium. The roles of the ‘lord’ and ‘lady’ as community leaders are examined, with particular regard to their position at the epicentre of radiating social relationships. Finally, the inverse importance of the mead- hall as a declining social institution and a developing literary construct is addressed. Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. The term ‘mead-hall’ is no longer current among English-speakers; it is used here as a shorthand notation for the Germanic customs and observances surrounding the consumption and distribution of food and drink in a ceremonial setting, the giving and receiving of honorifics and rewards, and the establishment of a communal identity expressed through formal relationships to a pair of individuals whom we may call the ‘lord’ and ‘lady’. It further relates to a set of traditions concerning hospitality offered to strangers, informal entertainment and the maintenance of wider social relationships. -

Harem Literature and the Question of Representational Authenticity

Contemporary Literary Review India CLRI Brings articulate writings for articulate readers. eISSN 2394-6075 | Vol 5, No 4, CLRI November 2018 | p. 33-46 Confronting Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf in the Digital Age Arnab Chatterjee Faculty Member, Department of English, Sister Nivedita University, Kolkata. Abstract It is a fundamental fact that an epic documents the exploits of certain characters on a scale that sometimes crosses the limits of both space and time; in fact, these features account for the “grand style” of any epic composed. Coupled with its bravura sweep, any epic is also a faithful documentation of the age in which it is written, something that Prof. E.M.W. Tillyard calls its “choric” quality. However, in the digital age, with the advent of animation and other such modes of representation, much of the erstwhile grandeur of the traditional epics seems to have been lost, and this brings us closer to Walter Benjamin’s remark that in the mechanical age, a work of art loses is pseudo-divine aura as we tend to have “copies” of the work that is readily Contemporary Literary Review India | eISSN 2394-6075 | Vol 5, No 4, CLRI November 2018 | Page 33 Confronting Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf in the Digital Age Arnab Chatterjee consumed. Taking clues from such theorists, this proposed paper is an attempt to locate Beowulf in the digital age and within the ‘mechanics’ of representation called “animation pictures” and alternative narratological strategies that tend to compromise not only with its original tone, but also with the story line. Keywords Animation, Grand style, Digital, Walter Benjamin, Narratological. -

Beowulf to Ancient Greece: It Is T^E First Great Work of a Nationai Literature

\eowulf is to England what Hcmer's ///ac/ and Odyssey are Beowulf to ancient Greece: it is t^e first great work of a nationai literature. Becwulf is the mythical and literary record of a formative stage of English civilization; it is also an epic of the heroic sources of English cuitu-e. As such, it uses a host of tra- ditional motifs associated with heroic literature all over the world. Liks most early heroic literature. Beowulf is oral art. it was hanaes down, with changes, and embe'lishrnents. from one min- strel to another. The stories of Beowulf, like those of all oral epics, are traditional ones, familiar to tne audiences who crowded around the harp:st-bards in the communal halls at night. The tales in the Beowulf epic are the stories of dream and legend, of monsters and of god-fashioned weapons, of descents to the underworld and of fights with dragons, of the hero's quest and of a community threat- ened by the powers of evil. Beowulf was composed in Old English, probably in Northumbria in northeast England, sometime between the years 700 and 750. The world it depicts, however, is much older, that of the early sixth century. Much of the material of the poem is based on early folk legends—some Celtic, some Scandinavian. Since the scenery de- scribes tne coast of Northumbna. not of Scandinavia, it has been A Celtic caldron. MKer-plateci assumed that the poet who wrote the version that has come down i Nl ccnlun, B.C.). to us was Northumbrian. -

Mytil Nndhlstory

212 / Robert E. Bjork I chayter tt and Herebeald, the earlier swedish wars, and Daeghrefn, 242g-250ga; (26) weohstan,s slaying Eanmund in the second Swedish-wars-,2611-25a; of (27-29)Hygelac's fall, and the battle at Ravenswood in the earlier Swedish war, 2910b-98. 8. For a full discussion, see chapter I l. 9. The emendation was first suggested by Max Rieger (lg7l,4l4). MytIL nndHlstory D. Niles W loh, SU*Uryt Nineteenth-century interpret ations of B eowutf , puticululy mythology that was then in vogue' in Germany, fell underthe influence of the nature or Indo- More recently, some critics have related the poem to ancient Germanic feature b*op"un rnyih -O cult or to archetypes that are thought to be a universal of nu-un clnsciousness. Alternatively, the poem has been used as a source of the poem' knowledge concerning history. The search for either myth or history in useful however,-is attended by severe and perhaps insurmountable difficulties' More may be attempts to identify the poem as a "mythistory" that confirmed a set of fabulous values amongthe Anglo-saxons by connecting their current world to a ancesfral past. /.1 Lhronology 1833: Iohn Mitchell Kemble, offering a historical preface to his edition of the poem' locates the Geats in Schleswig. 1837: Kemble corrects his preface to reflect the influence of Jakob Grimm; he identifies the first "Beowulf" who figures in the poem as "Beaw," the agricultural deity. Karl Miillenhoff (1849b), also inspired by Grimm, identifies the poem as a Germanic meteorological myth that became garbled into a hero tale on being transplanted to England. -

Beowulf: the Movie Name: Date

Beowulf: The Movie Name:___________________________________ Date:_______________ Block:______ NOTE: This movie does not follow our texts. It takes the classic and adds “Hollywood” to it, so you will need to watch and listen closely. The questions for this movie will focus on broader themes and analysis. To get started, here is a term which may be unfamiliar and definition to help you gain perspective on the religious references in this movie. Ragnarok: refers to a series of major events, including a great battle foretold to ultimately result in the death of a number of major figures (including the gods Odin, Thor, and Freya), the occurrence of various natural disasters, and the subsequent submersion of the world in water. Afterwards, the world resurfaces anew and fertile, the surviving gods meet, and the world is repopulated by two human survivors. DIRECTIONS: Please answer each of these questions with at least two complete sentences. You can always use more ! “I don’t know” and/or “Who cares” will not be acceptable answers. 1. Why do you think they used an animation style in this movie? What does it add to the quality of the movie? 2. What sets Wealthow apart from the other Danish women? 3. Why do you think the writers made Grendel be Hrothgar’s son? 4. Was the portrayal of Grendel accurate in your opinion? Explain. 5. What is symbolic about the Dragon’s Cup and why was it added to the movie? 6. Analyze the relationship between Wealthow and Hrothgar. 7. Are the party/feast scenes as you imagined when reading the epic poem Beowulf? Explain. -

Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2013 Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation VanDonkelaar, Ilse Schweitzer, "Old English Ecologies: Environmental Readings of Anglo-Saxon Texts and Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 216. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/216 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OLD ENGLISH ECOLOGIES: ENVIRONMENTAL READINGS OF ANGLO-SAXON TEXTS AND CULTURE by Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Western Michigan University December 2013 Doctoral Committee: Jana K. Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Eve Salisbury, Ph.D. Richard Utz, Ph.D. Sarah Hill, Ph.D. OLD ENGLISH ECOLOGIES: ENVIRONMENTAL READINGS OF ANGLO-SAXON TEXTS AND CULTURE Ilse Schweitzer VanDonkelaar, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2013 Conventionally, scholars have viewed representations of the natural world in Anglo-Saxon (Old English) literature as peripheral, static, or largely symbolic: a “backdrop” before which the events of human and divine history unfold. In “Old English Ecologies,” I apply the relatively new critical perspectives of ecocriticism and place- based study to the Anglo-Saxon canon to reveal the depth and changeability in these literary landscapes. -

Filmography for Beowulf (2007) Directed By: Robert Zemeckis

Audrey Crawford and Tynisha Ferguson Dr. Koster Engl 510 May 23, 2011 Filmography for Beowulf (2007) Directed by: Robert Zemeckis Screenplay by: Neil Gaiman and Roger Avary Featuring: Angelina Jolie, Crispin Hellion Glover, and Ray Winstone. DVD: Paramount Pictures, 2007. 115 mins. IMDB SITE http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0442933/ Cast: Ray Winstone Beowulf Anthony Hopkins Hrothgar John Malkovich Unferth Robin Wright Penn Wealthrow Brendan Gleesson Wiglaf Crispin Hellion Glover Grendel Alison Lohman Ursula Angelina Jolie Grendel’s Mother Script: No Script Available Major Reviews: New York Times, http://movies.nytimes.com/2007/11/16/movies/16beow.html CNN, http://www.cnn.com/2007/SHOWBIZ/Movies/11/16/review.beowulf/index.html?iref=allsearch Beowulf Website: http://www.beowulfmovie.com/ Video Link (youtube.com): How it should have ended: Beowulf Synopsis: (from Artist Direct) Audrey Crawford and Tynisha Ferguson Dr. Koster Engl 510 May 23, 2011 Inspired by the epic Old English poem of the same name, director Robert Zemeckis’ digitally rendered film follows the Scandinavian hero Beowulf (Ray Winstone) as he fights to protect the Danes from a ferocious beast named Grendel (Crispin Glover). Though at first Grendel seems invincible, Beowulf eventually manages to defeat him in a desperate battle to the death. Devastated by her son’s violent demise at the hands of Beowulf, Grendel’s mother (Angelina Jolie,) sets out in search of revenge. Later, Beowulf faces the biggest challenge of his life when he attempts to slay a powerful dragon. Anthony Hopkins, Robin Wright Penn, Alison Lohman, John Malkovich and Brendan Gleeson co-star in an epic fantasy adventure penned by Roger Avary. -

Beowulf Study Guide Author Biography 2

Beowulf Study Guide by Course Hero the narrator shows glimpses of many characters' feelings and What's Inside viewpoints. TENSE j Book Basics ................................................................................................. 1 Beowulf is told primarily in the past tense. d In Context ..................................................................................................... 1 ABOUT THE TITLE Beowulf is named after its heroic protagonist, Beowulf, as a a Author Biography ..................................................................................... 2 way of further honoring his achievements and moral character. h Characters ................................................................................................... 2 k Plot Summary ............................................................................................. 6 d In Context c Section Summaries ................................................................................. 9 Beowulf is the oldest existing Old English poem. While the g Quotes ......................................................................................................... 15 story and its historical elements arguably take place between l Symbols ....................................................................................................... 17 the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 8th century, it was most likely put into its current written form centuries later. The m Themes ....................................................................................................... -

Beowulf's Loyal Soldier, Stayed and Fought Dragon When Rest of Geats

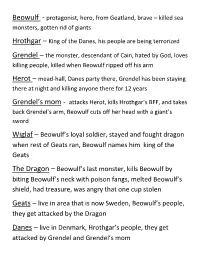

Beowulf - protagonist, hero, from Geatland, brave – killed sea monsters, gotten rid of giants Hrothgar – King of the Danes, his people are being terrorized Grendel – the monster, descendant of Cain, hated by God, loves killing people, killed when Beowulf ripped off his arm Herot – mead-hall, Danes party there, Grendel has been staying there at night and killing anyone there for 12 years Grendel’s mom - attacks Herot, kills Hrothgar’s BFF, and takes back Grendel’s arm, Beowulf cuts off her head with a giant’s sword Wiglaf – Beowulf’s loyal soldier, stayed and fought dragon when rest of Geats ran, Beowulf names him king of the Geats The Dragon – Beowulf’s last monster, kills Beowulf by biting Beowulf’s neck with poison fangs, melted Beowulf’s shield, had treasure, was angry that one cup stolen Geats – live in area that is now Sweden, Beowulf’s people, they get attacked by the Dragon Danes – live in Denmark, Hrothgar’s people, they get attacked by Grendel and Grendel’s mom What actions make Beowulf an epic hero?: look at chart….this will be a short essay question on test (you write a paragraph) -Describe the home of Grendel and his mother: dark, mysterious swamp, no one knows how deep it, hell on earth, burns at night, rain is black, mist steams like black clouds, lake covered with frozen spray, surrounded by snakelike roots, a deer won’t even enter the water to save itself from hunting dogs .