John Gardner's Grendel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle with Grendel

That Herot would be his to command. And then He declared: 385 ' "No one strange to this land Has ever been granted what I've given you, No one in all the years of my rule. Make this best of all mead-halls yours, and then Keep it free of evil, fight 390 With glory in your heart! Purge Herot And your ship will sail home with its treasure-holds full." . The feast ends. Beowulf and his men take the place of Hrothgar's followers and lie down to sleep in Herot. Beowulf, however, is wakeful, eager to meet his enemy. The Battle with Grendel 8 Out from the marsh, from the foot of misty Hills and bogs, bearing God's hatred, Grendel came, hoping to kill 395 Anyone he could trap on this trip to high Herot. He moved quickly through the cloudy night, Up from his swampland, sliding silently Toward that gold-shining hall. He had visited Hrothgar's Home before, knew the way— 4oo But never, before nor after that night, Found Herot defended so firmly, his reception So harsh. He journeyed, forever joyless, Bronze coin showing a Straight to the door, then snapped it open, warrior killing a monster. Tore its iron fasteners with a touch, 405 And rushed angrily over the threshold. He strode quickly across the inlaid Floor, snarling and fierce: His eyes Gleamed in the darkness, burned with a gruesomeX Light. Then he stopped, seeing the hall 4io Crowded with sleeping warriors, stuffed With rows of young soldiers resting together. And his heart laughed, he relished the sight, Intended to tear the life from those bodies By morning; the monster's mind was hot 415 With the thought of food and the feasting his belly Would soon know. -

Uncovering the Origins of Grendel's Mother by Jennifer Smith 1

Smith 1 Ides, Aglæcwif: That’s No Monster, That’s My Wife! Uncovering the Origins of Grendel’s Mother by Jennifer Smith 14 May 1999 Grendel’s mother has often been relegated to a secondary role in Beowulf, overshadowed by the monstrosity of her murderous son. She is not even given a name of her own. As Keith Taylor points out, “none has received less critical attention than Grendel’s mother, whom scholars of Beowulf tend to regard as an inherently evil creature who like her son is condemned to a life of exile because she bears the mark of Cain” (13). Even J. R. R. Tolkien limits his ground-breaking critical treatment of the poem and its monsters to a discussion of Grendel and the dragon. While Tolkien does touch upon Grendel’s mother, he does so only in connection with her infamous son. Why is this? It seems likely from textual evidence and recent critical findings that this reading stems neither from authorial intention nor from scribal error, but rather from modern interpretations of the text mistakenly filtered through twentieth-century eyes. While outstanding debates over the religious leanings of the Beowulf poet and the dating of the poem are outside the scope of this essay, I do agree with John D. Niles that “if this poem can be attributed to a Christian author composing not earlier than the first half of the tenth century […] then there is little reason to read it as a survival from the heathen age that came to be marred by monkish interpolations” (137). -

An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe from the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages

PETTIT, MATTHEW JOSEPH, M.A. Removing the Christian Mask: An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe From the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. (2008) Directed by Dr. Amy Vines. 85 pp. The aim of this thesis is to de-center Christianity from medieval scholarship in a study of canonized northwestern European war narratives from the late antiquity to the late Middle Ages by unraveling three complex theological frameworks interweaved with Scandinavian polytheistic beliefs. These frameworks are presented in three chapters concerning warrior cults, war rituals, and battle iconography. Beowulf, The History of the Kings of Britain, and additional passages from The Wanderer and The Dream of the Rood are recognized as the primary texts in the study with supporting evidence from An Ecclesiastical History of the English People, eighth-century eddaic poetry, thirteenth- century Icelandic and Nordic sagas, and Le Morte d’Arthur. The study consistently found that it is necessary to alter current pedagogical habits in order to better develop the study of theology in medieval literature by avoiding the conciliatory practice of reading for Christian hegemony. REMOVING THE CHRISTIAN MASK: AN EXAMINATION OF SCANDINAVIAN WAR CULTS IN MEDIEVAL NARRATIVES OF NORTHWESTERN EUROPE FROM THE LATE ANTIQUITY TO THE MIDDLE AGES by Matthew Joseph Pettit A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ______________________________ Committee Chair APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and Culture • Middle Ages Is the Period of Time

The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and culture • Middle Ages is the period of time Art that extends between the ancient classical period and the Language history Renaissance • Middle Ages extends from the The spread of Christianity Roman withdrawal and the Anglo Saxon invasion in 5th century to the accession of the House of Tudor in Beowulf th the late 15 century 1 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The earlier part of this period is called The dark Ages • Middle Ages is divided in two parts: the first is named Anglo Saxon Period or Old English Period (449-1066); the second is named the Anglo Norman Period or Middle English period (1066- 1485) 2 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Anglo Saxon or Old English period (449-1066) • In 449 the tribes of Jutes, angles and Saxons from Denmark and Northern Germany started to invade Britain defeating original Celtic people who escaped to Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. 3 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The language of these tribes was the Anglo- Saxon • The country was divided into 7 kingdoms, which soon had to face Viking invasions. The joined the forces and managed to defeat Vikings 4 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Life and culture • Life in Saxon England: society was based on the family unit, the clan, the tribe • The code of values was based on courage, loyalty to the ruler, generosity. The most important hero in a poem of this period is Beowulf 5 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The culture was military, based on war -

Medievalism and the Shocks of Modernity: Rewriting Northern Legend from Darwin to World War II

Medievalism and the Shocks of Modernity: Rewriting Northern Legend from Darwin to World War II by Dustin Geeraert A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2016 by Dustin Geeraert 1 Abstract Literary medievalism has always been critically controversial; at various times it has been dismissed as reactionary or escapist. This survey of major medievalist writers from America, England, Ireland and Iceland aims to demonstrate instead that medievalism is one of the characteristic literatures of modernity. Whereas realist fiction focuses on typical, plausible or common experiences of modernity, medievalist literature is anything but reactionary, for it focuses on the intellectual circumstances of modernity. Events such as the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, many political revolutions, the world wars, and the scientific discoveries of Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and above all those of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), each sent out cultural shockwaves that changed western beliefs about the nature of humanity and the world. Although evolutionary ideas remain controversial in the humanities, their importance has not been lost on medievalist writers. Thus, intellectual anachronisms pervade medievalist literature, from its Romantic roots to its postwar explosion in popularity, as some of the greatest writers of modern times offer new perspectives on old legends. The first chapter of this study focuses on the impact of Darwin’s ideas on Victorian epic poems, particularly accounts of natural evolution and supernatural creation. The second chapter describes how late Victorian medievalists, abandoning primitivism and claims to historicity, pushed beyond the form of the retelling by simulating medieval literary genres. -

Tolkien's Creative Technique: <I>Beowulf</I> and <I>The Hobbit</I>

Volume 15 Number 3 Article 1 Spring 3-15-1989 Tolkien's Creative Technique: Beowulf and The Hobbit Bonniejean Christensen Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Christensen, Bonniejean (1989) "Tolkien's Creative Technique: Beowulf and The Hobbit," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 15 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol15/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Asserts that “The Hobbit, differing greatly in tone, is nonetheless a retelling of the incidents that comprise the plot and the digressions in both parts of Beowulf.” However, his retelling is from a Christian point of view. Additional Keywords Beowulf—Influence on The Hobbit; olkien,T J.R.R. -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

Harem Literature and the Question of Representational Authenticity

Contemporary Literary Review India CLRI Brings articulate writings for articulate readers. eISSN 2394-6075 | Vol 5, No 4, CLRI November 2018 | p. 33-46 Confronting Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf in the Digital Age Arnab Chatterjee Faculty Member, Department of English, Sister Nivedita University, Kolkata. Abstract It is a fundamental fact that an epic documents the exploits of certain characters on a scale that sometimes crosses the limits of both space and time; in fact, these features account for the “grand style” of any epic composed. Coupled with its bravura sweep, any epic is also a faithful documentation of the age in which it is written, something that Prof. E.M.W. Tillyard calls its “choric” quality. However, in the digital age, with the advent of animation and other such modes of representation, much of the erstwhile grandeur of the traditional epics seems to have been lost, and this brings us closer to Walter Benjamin’s remark that in the mechanical age, a work of art loses is pseudo-divine aura as we tend to have “copies” of the work that is readily Contemporary Literary Review India | eISSN 2394-6075 | Vol 5, No 4, CLRI November 2018 | Page 33 Confronting Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf in the Digital Age Arnab Chatterjee consumed. Taking clues from such theorists, this proposed paper is an attempt to locate Beowulf in the digital age and within the ‘mechanics’ of representation called “animation pictures” and alternative narratological strategies that tend to compromise not only with its original tone, but also with the story line. Keywords Animation, Grand style, Digital, Walter Benjamin, Narratological. -

The Tale of Beowulf

The Tale of Beowulf William Morris The Tale of Beowulf Table of Contents The Tale of Beowulf............................................................................................................................................1 William Morris........................................................................................................................................2 ARGUMENT...........................................................................................................................................4 THE STORY OF BEOWULF.................................................................................................................6 I. AND FIRST OF THE KINDRED OF HROTHGAR.........................................................................7 II. CONCERNING HROTHGAR, AND HOW HE BUILT THE HOUSE CALLED HART. ALSO GRENDEL IS TOLD OF........................................................................................................................9 III. HOW GRENDEL FELL UPON HART AND WASTED IT..........................................................11 IV. NOW COMES BEOWULF ECGTHEOW'S SON TO THE LAND OF THE DANES, AND THE WALL−WARDEN SPEAKETH WITH HIM.............................................................................13 V. HERE BEOWULF MAKES ANSWER TO THE LAND−WARDEN, WHO SHOWETH HIM THE WAY TO THE KING'S ABODE................................................................................................15 VI. BEOWULF AND THE GEATS COME INTO HART...................................................................17 -

From Beowulf “Hail, Hrothgar! Higlac Is My Cousin and My King; the Days

From Beowulf “Hail, Hrothgar! Higlac is my cousin and my king; the days Of my youth have been filled with glory. Now Grendel’s Name has echoed in our land: Sailors Have brought us stories of Herot, the best Of all mead-halls, deserted and useless when the moon Hangs in skies the sun had lit, Light and life fleeing together. My people have said, the wisest, most knowing And best of them, that my duty was to go to the Danes’ Great King. They have seen my strength for themselves, Have watched me rise from the darkness of war, Dripping with my enemies’ blood. I drove Five great giants into chains, chased All of that race from the earth. I swam In the blackness of night, hunting monsters Out of the ocean, and killing them one By one; death was my errand and the fate They had earned. Now Grendel and I are called Together, and I’ve come. Grant me, then, Lord and protector of this noble place, A single request! I have come so far, Oh shelterer of warriors and your people’s loved friend, That this one favor you should not refuse me- That I, alone and with the help of my men, May purge all evil from this hall. I have heard, Too, that the monster’s scorn of men Is so great that he needs no weapons and fears none. Now will I. My lord Higlac Might think less of me if I let my sword Go where my feet were afraid to, if I hid Behind some broa linden shields: My hands Alone shall fight for me, struggle for life Against the monster. -

13 Reflections on Tolkien's Use of Beowulf

13 Reflections on Tolkien’s Use of Beowulf Arne Zettersten University of Copenhagen Beowulf, the famous Anglo-Saxon heroic poem, and The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Author of the Century”, 1 have been thor- oughly analysed and compared by a variety of scholars.2 It seems most appropriate to discuss similar aspects of The Lord of the Rings in a Festschrift presented to Nils-Lennart Johannesson with a view to his own commentaries on the language of Tolkien’s fiction. The immediate pur- pose of this article is not to present a problem-solving essay but instead to explain how close I was to Tolkien’s own research and his activities in Oxford during the last thirteen years of his life. As the article unfolds, we realise more and more that Beowulf meant a great deal to Tolkien, cul- minating in Christopher Tolkien’s unexpected edition of the translation of Beowulf, completed by J.R.R. Tolkien as early as 1926. Beowulf has always been respected in its position as the oldest Germanic heroic poem.3 I myself accept the conclusion that the poem came into existence around 720–730 A.D. in spite of the fact that there is still considerable debate over the dating. The only preserved copy (British Library MS. Cotton Vitellius A.15) was most probably com- pleted at the beginning of the eleventh century. 1 See Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, 2000. 2 See Shippey, T.A., The Road to Middle-earth, 1982, Pearce, Joseph, Tolkien. -

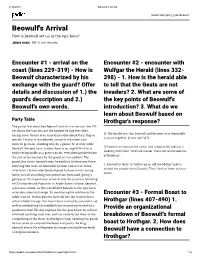

Beowulf's Arrival

2/16/2018 Beowulf's Arrival padlet.com/jenny_ryan/beowulf Beowulf's Arrival How is Beowulf set up as the epic hero? JENNY RYAN FEB 15, 2018 09:30AM Encounter #1 - arrival on the Encounter #2 - encounter with coast (lines 229-319) - How is Wulfgar the Herald (lines 332- Beowulf characterized by his 398) - 1. How is the herald able exchange with the guard? Offer to tell that the Geats are not details and discussion of 1.) the invaders? 2. What are some of guard's description and 2.) the key points of Beowulf's Beowulf's own words. introduction? 3. What do we learn about Beowulf based on Party Table Hrothgar's response? The guard rst describes Beowulf and his warriors on line 247. He claims the warriors are the boldest he had ever seen, 1) The herald saw that Beowulf and his men were honorable having never before seen armed men disembark their ship so and put together. (Lines 342-347). quickly. He also is immediately aware of the noble aura Beowulf gives off, claiming only by a glance he is truly noble. 2) Beowulf announces his name, and respectfully asks for a Beowulf, the epic hero, is described as so mighty that he is meeting with their “lord and master, the most renowned son easily recognizable as a great warrior, even distinguished from of Halfdane”. the rest of his warriors by the guard as true nobility. The guard also trusts Beowulf after he explains his business there, 3. Beowulf is there to “follow up an old friendship” and to believing him to be an honorable person who is true in his defend the people from Grendel.