Past and Future Lives of Grendel (Presentation)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle with Grendel

That Herot would be his to command. And then He declared: 385 ' "No one strange to this land Has ever been granted what I've given you, No one in all the years of my rule. Make this best of all mead-halls yours, and then Keep it free of evil, fight 390 With glory in your heart! Purge Herot And your ship will sail home with its treasure-holds full." . The feast ends. Beowulf and his men take the place of Hrothgar's followers and lie down to sleep in Herot. Beowulf, however, is wakeful, eager to meet his enemy. The Battle with Grendel 8 Out from the marsh, from the foot of misty Hills and bogs, bearing God's hatred, Grendel came, hoping to kill 395 Anyone he could trap on this trip to high Herot. He moved quickly through the cloudy night, Up from his swampland, sliding silently Toward that gold-shining hall. He had visited Hrothgar's Home before, knew the way— 4oo But never, before nor after that night, Found Herot defended so firmly, his reception So harsh. He journeyed, forever joyless, Bronze coin showing a Straight to the door, then snapped it open, warrior killing a monster. Tore its iron fasteners with a touch, 405 And rushed angrily over the threshold. He strode quickly across the inlaid Floor, snarling and fierce: His eyes Gleamed in the darkness, burned with a gruesomeX Light. Then he stopped, seeing the hall 4io Crowded with sleeping warriors, stuffed With rows of young soldiers resting together. And his heart laughed, he relished the sight, Intended to tear the life from those bodies By morning; the monster's mind was hot 415 With the thought of food and the feasting his belly Would soon know. -

An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe from the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages

PETTIT, MATTHEW JOSEPH, M.A. Removing the Christian Mask: An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe From the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. (2008) Directed by Dr. Amy Vines. 85 pp. The aim of this thesis is to de-center Christianity from medieval scholarship in a study of canonized northwestern European war narratives from the late antiquity to the late Middle Ages by unraveling three complex theological frameworks interweaved with Scandinavian polytheistic beliefs. These frameworks are presented in three chapters concerning warrior cults, war rituals, and battle iconography. Beowulf, The History of the Kings of Britain, and additional passages from The Wanderer and The Dream of the Rood are recognized as the primary texts in the study with supporting evidence from An Ecclesiastical History of the English People, eighth-century eddaic poetry, thirteenth- century Icelandic and Nordic sagas, and Le Morte d’Arthur. The study consistently found that it is necessary to alter current pedagogical habits in order to better develop the study of theology in medieval literature by avoiding the conciliatory practice of reading for Christian hegemony. REMOVING THE CHRISTIAN MASK: AN EXAMINATION OF SCANDINAVIAN WAR CULTS IN MEDIEVAL NARRATIVES OF NORTHWESTERN EUROPE FROM THE LATE ANTIQUITY TO THE MIDDLE AGES by Matthew Joseph Pettit A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ______________________________ Committee Chair APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and Culture • Middle Ages Is the Period of Time

The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and culture • Middle Ages is the period of time Art that extends between the ancient classical period and the Language history Renaissance • Middle Ages extends from the The spread of Christianity Roman withdrawal and the Anglo Saxon invasion in 5th century to the accession of the House of Tudor in Beowulf th the late 15 century 1 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The earlier part of this period is called The dark Ages • Middle Ages is divided in two parts: the first is named Anglo Saxon Period or Old English Period (449-1066); the second is named the Anglo Norman Period or Middle English period (1066- 1485) 2 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Anglo Saxon or Old English period (449-1066) • In 449 the tribes of Jutes, angles and Saxons from Denmark and Northern Germany started to invade Britain defeating original Celtic people who escaped to Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. 3 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The language of these tribes was the Anglo- Saxon • The country was divided into 7 kingdoms, which soon had to face Viking invasions. The joined the forces and managed to defeat Vikings 4 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Life and culture • Life in Saxon England: society was based on the family unit, the clan, the tribe • The code of values was based on courage, loyalty to the ruler, generosity. The most important hero in a poem of this period is Beowulf 5 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The culture was military, based on war -

Harem Literature and the Question of Representational Authenticity

Contemporary Literary Review India CLRI Brings articulate writings for articulate readers. eISSN 2394-6075 | Vol 5, No 4, CLRI November 2018 | p. 33-46 Confronting Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf in the Digital Age Arnab Chatterjee Faculty Member, Department of English, Sister Nivedita University, Kolkata. Abstract It is a fundamental fact that an epic documents the exploits of certain characters on a scale that sometimes crosses the limits of both space and time; in fact, these features account for the “grand style” of any epic composed. Coupled with its bravura sweep, any epic is also a faithful documentation of the age in which it is written, something that Prof. E.M.W. Tillyard calls its “choric” quality. However, in the digital age, with the advent of animation and other such modes of representation, much of the erstwhile grandeur of the traditional epics seems to have been lost, and this brings us closer to Walter Benjamin’s remark that in the mechanical age, a work of art loses is pseudo-divine aura as we tend to have “copies” of the work that is readily Contemporary Literary Review India | eISSN 2394-6075 | Vol 5, No 4, CLRI November 2018 | Page 33 Confronting Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf in the Digital Age Arnab Chatterjee consumed. Taking clues from such theorists, this proposed paper is an attempt to locate Beowulf in the digital age and within the ‘mechanics’ of representation called “animation pictures” and alternative narratological strategies that tend to compromise not only with its original tone, but also with the story line. Keywords Animation, Grand style, Digital, Walter Benjamin, Narratological. -

From Beowulf “Hail, Hrothgar! Higlac Is My Cousin and My King; the Days

From Beowulf “Hail, Hrothgar! Higlac is my cousin and my king; the days Of my youth have been filled with glory. Now Grendel’s Name has echoed in our land: Sailors Have brought us stories of Herot, the best Of all mead-halls, deserted and useless when the moon Hangs in skies the sun had lit, Light and life fleeing together. My people have said, the wisest, most knowing And best of them, that my duty was to go to the Danes’ Great King. They have seen my strength for themselves, Have watched me rise from the darkness of war, Dripping with my enemies’ blood. I drove Five great giants into chains, chased All of that race from the earth. I swam In the blackness of night, hunting monsters Out of the ocean, and killing them one By one; death was my errand and the fate They had earned. Now Grendel and I are called Together, and I’ve come. Grant me, then, Lord and protector of this noble place, A single request! I have come so far, Oh shelterer of warriors and your people’s loved friend, That this one favor you should not refuse me- That I, alone and with the help of my men, May purge all evil from this hall. I have heard, Too, that the monster’s scorn of men Is so great that he needs no weapons and fears none. Now will I. My lord Higlac Might think less of me if I let my sword Go where my feet were afraid to, if I hid Behind some broa linden shields: My hands Alone shall fight for me, struggle for life Against the monster. -

Beowulf's Arrival

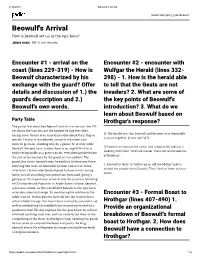

2/16/2018 Beowulf's Arrival padlet.com/jenny_ryan/beowulf Beowulf's Arrival How is Beowulf set up as the epic hero? JENNY RYAN FEB 15, 2018 09:30AM Encounter #1 - arrival on the Encounter #2 - encounter with coast (lines 229-319) - How is Wulfgar the Herald (lines 332- Beowulf characterized by his 398) - 1. How is the herald able exchange with the guard? Offer to tell that the Geats are not details and discussion of 1.) the invaders? 2. What are some of guard's description and 2.) the key points of Beowulf's Beowulf's own words. introduction? 3. What do we learn about Beowulf based on Party Table Hrothgar's response? The guard rst describes Beowulf and his warriors on line 247. He claims the warriors are the boldest he had ever seen, 1) The herald saw that Beowulf and his men were honorable having never before seen armed men disembark their ship so and put together. (Lines 342-347). quickly. He also is immediately aware of the noble aura Beowulf gives off, claiming only by a glance he is truly noble. 2) Beowulf announces his name, and respectfully asks for a Beowulf, the epic hero, is described as so mighty that he is meeting with their “lord and master, the most renowned son easily recognizable as a great warrior, even distinguished from of Halfdane”. the rest of his warriors by the guard as true nobility. The guard also trusts Beowulf after he explains his business there, 3. Beowulf is there to “follow up an old friendship” and to believing him to be an honorable person who is true in his defend the people from Grendel. -

Beowulf: the Movie Name: Date

Beowulf: The Movie Name:___________________________________ Date:_______________ Block:______ NOTE: This movie does not follow our texts. It takes the classic and adds “Hollywood” to it, so you will need to watch and listen closely. The questions for this movie will focus on broader themes and analysis. To get started, here is a term which may be unfamiliar and definition to help you gain perspective on the religious references in this movie. Ragnarok: refers to a series of major events, including a great battle foretold to ultimately result in the death of a number of major figures (including the gods Odin, Thor, and Freya), the occurrence of various natural disasters, and the subsequent submersion of the world in water. Afterwards, the world resurfaces anew and fertile, the surviving gods meet, and the world is repopulated by two human survivors. DIRECTIONS: Please answer each of these questions with at least two complete sentences. You can always use more ! “I don’t know” and/or “Who cares” will not be acceptable answers. 1. Why do you think they used an animation style in this movie? What does it add to the quality of the movie? 2. What sets Wealthow apart from the other Danish women? 3. Why do you think the writers made Grendel be Hrothgar’s son? 4. Was the portrayal of Grendel accurate in your opinion? Explain. 5. What is symbolic about the Dragon’s Cup and why was it added to the movie? 6. Analyze the relationship between Wealthow and Hrothgar. 7. Are the party/feast scenes as you imagined when reading the epic poem Beowulf? Explain. -

BEOWULF SUMMARY Chapter 1: We Meet King Hrothgar (The Victim)

BEOWULF SUMMARY Chapter 1: We meet King Hrothgar (the victim) and Grendel (the monster). We learn Grendel is pure evil and was created from death. Chapter 2: Grendel attacks the Danes when they’re sleeping. He murders thirty men at once and then keeps coming back at night for 12 years. Chapter 3: Beowulf brings 13 men across the sea to defeat Grendel. Chapter 4: Beowulf arrives in Hrothgar’s kingdom and makes his way to the castle. Chapter 5: Beowulf arrives at the castle and is announced to the king. He is described as a wise, powerful, and brave fighter. Chapter 6: Beowulf meets Hrothgar and he says that Beowulf is as strong as 30 men and is very confident in his ability to defeat the monster. Beowulf talks about how his own people told him to come help Hrothgar, he rid the world of giants, and will fight Grendel with his bare hands. Chapter 7: Beowulf came to help Hrothgar, not just because he wants to fight Grendel, but because he is repaying the debt that his father owes. Hrothgar helped Edgetho end a feud he started when he murdered someone. Chapter 8: Unferth, a disgruntled soldier, calls Beowulf out as a foolish man who constantly puts himself in danger by seeking out monsters to defeat. Beowulf responds by saying that even though he seeks out monsters,it doesn’t matter since he always wins the fight. Chapter 9: Beowulf continues to discuss all the adventures he’s gone on and all the monsters he’s faced. Once done the queen passes around drinks and everyone starts celebrating. -

Filmography for Beowulf (2007) Directed By: Robert Zemeckis

Audrey Crawford and Tynisha Ferguson Dr. Koster Engl 510 May 23, 2011 Filmography for Beowulf (2007) Directed by: Robert Zemeckis Screenplay by: Neil Gaiman and Roger Avary Featuring: Angelina Jolie, Crispin Hellion Glover, and Ray Winstone. DVD: Paramount Pictures, 2007. 115 mins. IMDB SITE http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0442933/ Cast: Ray Winstone Beowulf Anthony Hopkins Hrothgar John Malkovich Unferth Robin Wright Penn Wealthrow Brendan Gleesson Wiglaf Crispin Hellion Glover Grendel Alison Lohman Ursula Angelina Jolie Grendel’s Mother Script: No Script Available Major Reviews: New York Times, http://movies.nytimes.com/2007/11/16/movies/16beow.html CNN, http://www.cnn.com/2007/SHOWBIZ/Movies/11/16/review.beowulf/index.html?iref=allsearch Beowulf Website: http://www.beowulfmovie.com/ Video Link (youtube.com): How it should have ended: Beowulf Synopsis: (from Artist Direct) Audrey Crawford and Tynisha Ferguson Dr. Koster Engl 510 May 23, 2011 Inspired by the epic Old English poem of the same name, director Robert Zemeckis’ digitally rendered film follows the Scandinavian hero Beowulf (Ray Winstone) as he fights to protect the Danes from a ferocious beast named Grendel (Crispin Glover). Though at first Grendel seems invincible, Beowulf eventually manages to defeat him in a desperate battle to the death. Devastated by her son’s violent demise at the hands of Beowulf, Grendel’s mother (Angelina Jolie,) sets out in search of revenge. Later, Beowulf faces the biggest challenge of his life when he attempts to slay a powerful dragon. Anthony Hopkins, Robin Wright Penn, Alison Lohman, John Malkovich and Brendan Gleeson co-star in an epic fantasy adventure penned by Roger Avary. -

Beowulf Study Guide Author Biography 2

Beowulf Study Guide by Course Hero the narrator shows glimpses of many characters' feelings and What's Inside viewpoints. TENSE j Book Basics ................................................................................................. 1 Beowulf is told primarily in the past tense. d In Context ..................................................................................................... 1 ABOUT THE TITLE Beowulf is named after its heroic protagonist, Beowulf, as a a Author Biography ..................................................................................... 2 way of further honoring his achievements and moral character. h Characters ................................................................................................... 2 k Plot Summary ............................................................................................. 6 d In Context c Section Summaries ................................................................................. 9 Beowulf is the oldest existing Old English poem. While the g Quotes ......................................................................................................... 15 story and its historical elements arguably take place between l Symbols ....................................................................................................... 17 the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 8th century, it was most likely put into its current written form centuries later. The m Themes ....................................................................................................... -

Lecenos of Lbjrn, Houp of Krncs

LecENos OF LBJRn, Houp OF KrNcs Manr-raNs Ossonx 'The words Scylding and Skjoldung (with the hybrid plural form Skjoldungs) will be used inter- changeably as adjectives throughout this essay, depending on whether the context is English or Scan- dinavian 2 For details see Bruce 2002:3L-42. The Angio-Saxon royai genealogies (and their political di- mension, or their implications for the dating of Beowulfl have been the topic of lively discussion, no- tablyby Sisam 1953, Murray 7981:1,04-6, Davis 1992, Newton 1"993:54 76, and Meaney 2003. PART III The Earliest Notices of the Skjiildung Kings The Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, set entirely in Scandinavia, begins with a 52 line proem cel- ebrating the "Spear Danes" and especially Scyld Scefing ("Scyld descendant of Scef"), found- er of the Scylding dynasty. Outside of Beowulf, which cannot be dated with certainty,3 the earliest mention of Scyld is in the A-text of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, the so-called Parker Chronicle. Here under the year 855, in the course of an elaborate pseudo-genealogy of King ,€thelwulf of Wessex (the father of King Alfred the Great), Scyld is introduced as Sceldwea Heremoding ("Scyld son of Heremod") and is said to have lived some twenty-eight genera namely in tions before 6the1wu1f.a Only once in O1d English tradition outside of Beowulf - the late tenth century Latin Chronicon of .€thelweard, who takes pride in his descent from is Scyld identified as the immediate son of Scef. ,4thelweard's account of King,4thelwulf - the origins of a founding king of Denmark is similar to the story of the coming of Scyld in Beowulf. -

Hygelac's Only Daughter: a Present, a Potentate and a Peaceweaver In

Studia Neophilologica 000: 1–7, 2006 0 Hygelac’s only daughter: a present, a potentate and a 0 peaceweaver in Beowulf 5 ALARIC HALL 5 The women of Beowulf have enjoyed extensive study in recent years, but one has 10 escaped the limelight: the only daughter of Hygelac, king of the Geats and Beowulf’s 10 lord. But though this daughter is mentioned only fleetingly, a close examination of the circumstances of her appearance and the words in which it is couched affords new perspectives on the role of women in Beowulf and on the nature of Hygelac’s kingship. Hygelac’s only daughter is given as part of a reward to Hygelac’s retainer 15 Eofor for the slaying of the Swedish king Ongentheow. Beowulf refers to this reward 15 with the unique noun ofermaðmas, traditionally understood to mean ‘‘great treasures’’. I argue, however, that ofermaðmas at least potentially means ‘‘excessive treasures’’. Developing this reading implies a less favourable assessment of Hygelac’s actions here than has previously been inferred. I argue further that the excess in 20 Hygelac’s treasure-giving derives specifically from his gift of his only daughter, and 20 the consequent loss to the Geats of the possibility of a diplomatic marriage through which they might end their feud with the Swedes. A reconsideration of Hygelac’s only daughter, then, offers new perspectives on the semantics of ofermaðum,on Hygelac’s kingship, and on women in Beowulf. 25 Hygelac’s daughter is mentioned in the speech which is delivered by the messenger 25 who announces Beowulf’s death to the Geats after Beowulf’s dragon-fight.