Hegemonic Masculinity in the Walking Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flowers for Algernon.Pdf

SHORT STORY FFlowerslowers fforor AAlgernonlgernon by Daniel Keyes When is knowledge power? When is ignorance bliss? QuickWrite Why might a person hesitate to tell a friend something upsetting? Write down your thoughts. 52 Unit 1 • Collection 1 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand subplots and Reader/Writer parallel episodes. Reading Skills Track story events. Notebook Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Subplots and Parallel Episodes A long short story, like the misled (mihs LEHD) v.: fooled; led to believe one that follows, sometimes has a complex plot, a plot that con- something wrong. Joe and Frank misled sists of intertwined stories. A complex plot may include Charlie into believing they were his friends. • subplots—less important plots that are part of the larger story regression (rih GREHSH uhn) n.: return to an earlier or less advanced condition. • parallel episodes—deliberately repeated plot events After its regression, the mouse could no As you read “Flowers for Algernon,” watch for new settings, charac- longer fi nd its way through a maze. ters, or confl icts that are introduced into the story. These may sig- obscure (uhb SKYOOR) v.: hide. He wanted nal that a subplot is beginning. To identify parallel episodes, take to obscure the fact that he was losing his note of similar situations or events that occur in the story. intelligence. Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described deterioration (dih tihr ee uh RAY shuhn) on page 55 as you read this story. n. used as an adj: worsening; declining. Charlie could predict mental deterioration syndromes by using his formula. -

USCCB Prayers a Rosary for Life: the Sorrowful Mysteries

USCCB Prayers A Rosary for Life: The Sorrowful Mysteries The following meditations on the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary are offered as a prayer for all life, from conception to natural death. The First Sorrowful Mystery The Agony in the Garden Prayer Intention: For all who are suffering from abandonment or neglect, that compassionate individuals will come forward to offer them comfort and aid. Jesus comes with his disciples to the garden of Gethsemane and prays to be delivered from his Passion, but most of all, to do the Father's will. Let us pray that Christ might hear the prayers of all who suffer from the culture of death, and that he might deliver them from the hands of their persecutors. Our Father... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: hear the cries of innocent children taken from their mothers' wombs and pray for us sinners now, and at the hour of our death. Amen. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: soothe the aching hearts of those afraid to welcome their child. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: guide the heart of the frightened unwed mother who turns to you. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: move the hearts of legislators to defend life from conception to natural death. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: be with us when pain causes us to forget the inherent value of all human life. Hail Mary, full of grace... Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows: pray for the children who have forgotten their elderly parents. -

Story of Andree Trip Is

TTO yW»}ATHIPB— ^ • B o re ^ by'o. S. W*«Ui«r BawiWf . _ , ■'i->-^*'-Lf. v-*^ .■NEt=-wW»s.WJN.. -■■I'': r -- m '■ - - t — t ; w « vv—C aniD. EEurtfoitl. ' ■ >- r -'ATiacA.isB oaiinr‘‘CinMroii«^^ ' -'ter tlio M9Bth of Ai«iirt,‘lM6 \ Secretary Hyde Says Russia Governs French smd Dry Agents Had Raided Jer T IS^S MADE FRIENDS Happily — Were Divided WITH THE PHOTOGRAPHEKvl France Also is Hit by S to m ; Caus^ latest Price De TO SERV£ SENTENCE sey Plant When Gang Ap Sqn Francisco, , Sept. 20, Crews of Small Boats Res pression by Speculating by Race, Language and (A P )—Dr. Arthur C. Pillsbury, pears — Agents Are Dis Berkeley scientist, returning yes terday from the South Seas, cuer-False Rumor Si^s • on Chicago Exchange. Red Leader Who is in Russia Religion. where he donned a diver’s uni armed, One is Shot. form and photographed much Says He WiU Not Go Back 1 submarine life, told this one: That Big Cnnarder is k Washington, Sept. 20.— (A P.)— Geneva, Sept. 20.,— (A P.)—Cana 1 “Beautiful fish made friends 1 with me. ’ So great was their The Russi^ governnient stood Elizabeth, N. J., Sept. 20— (AP) da was held up before the League Peril— Much Damage R ^ On His Friends. Federal, State and local authorities curiosity that they gathered in charged today by Secretary Hyde of Nations Assembly today, as _ a hordes so’ L could not see to do wth partial responsibility for the sought today to round up a gang of shining example to peoples who are iny work, i would have to brush ported in Coast Towns. -

Misdemeanor Warrant List

SO ST. LOUIS COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE Page 1 of 238 ACTIVE WARRANT LIST Misdemeanor Warrants - Current as of: 09/26/2021 9:45:03 PM Name: Abasham, Shueyb Jabal Age: 24 City: Saint Paul State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/05/2020 415 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFFIC-9000 Misdemeanor Name: Abbett, Ashley Marie Age: 33 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 03/09/2020 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Abbott, Alan Craig Age: 57 City: Edina State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 09/16/2019 500 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Disorderly Conduct Misdemeanor Name: Abney, Johnese Age: 65 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/18/2016 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Shoplifting Misdemeanor Name: Abrahamson, Ty Joseph Age: 48 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/24/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Trespass of Real Property Misdemeanor Name: Aden, Ahmed Omar Age: 35 City: State: Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 06/02/2016 485 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFF/ACC (EXC DUI) Misdemeanor Name: Adkins, Kyle Gabriel Age: 53 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/28/2013 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Aguilar, Raul, JR Age: 32 City: Couderay State: WI Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/17/2016 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Driving Under the Influence Misdemeanor Name: Ainsworth, Kyle Robert Age: 27 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 11/22/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Theft Misdemeanor ST. -

Choosing to Suffer As a Consequence of Expecting to Suffer: Why Do People Do It? Ronald Comer and James D

Journal ol Personality and Social Psychology 1975, Vol. 32, No. 1, 92-101 Choosing to Suffer as a Consequence of Expecting to Suffer: Why Do People Do It? Ronald Comer and James D. Laird Clark University In three previous studies, most subjects who anticipated having to perform an unpleasant task (e.g., eat a worm) and who were then offered a choice of that or a neutral task chose the unpleasant task. It was hypothesized that this "choosing to suffer" effect was produced by the subjects' attempt to make sense of their anticipated suffering, through one of three kinds of change in their conception of themselves and the situation: (a) they deserved the suffer- ing, (b) they were brave, or (c) the worm was not too bad. Subjects antici- pating a neutral task did not change on these measures, while subjects eating a worm changed significantly, indicating that anticipated suffering did cause the predicted reconceptualizations. Changes in these three kinds of conception predicted subject's choice or not of eating the worm, indicating that these changes produced the subsequent choice. Finally, subjects who saw them- selves as either more brave or more deserving also chose to administer painful electric shocks to themselves, while subjects who had changed their concep- tions of the worm did not, indicating that these conceptual changes can affect behavior in situations different from that which initially caused the conceptual changes. In a few more or less unrelated studies, a man & Radtke, 1970). Clearly then, some- particularly paradoxical bit of behavior has thing happens during the interval between a been observed, that subjects often "choose" subject's assignment to a negative event and to suffer as a consequence of having expected his subsequent choice which influences most to suffer. -

LLT 180 Lecture 22 1 Today We're Gonna Pick up with Gottfried Von Strassburg. As Most of You Already Know, and It's Been Alle

LLT 180 Lecture 22 1 Today we're gonna pick up with Gottfried von Strassburg. As most of you already know, and it's been alleged and I readily admit, that I'm an occasional attention slut. Obviously, otherwise, I wouldn't permit it to be recorded for TV. And, you know, if you pick up your Standard today, it always surprises me -- actually, if you live in Springfield, you might have met me before without realizing it. I like to cook and a colleague in the department -- his wife's an editor for the Springfield paper and she also writes a weekly column for the "Home" section. And so he and I were talking about pans one day and I was, you know, saying, "Well," you know, "so many people fail to cook because they don't have the perfect pan." And she was wanting to write an article about pans. She'd been trying to convince him to buy better pans. And so she said, "Hey, would you pose for a picture with pans? I'm writing this article." And so I said, "Oh, what the heck." And so she came over and took this photo. And a couple of weeks later, I opened Sunday morning's paper -- 'cause I knew it was gonna be in that week -- and went over to the "Home" section. And there was this color photo, about this big, and I went, "Oh, crap," you know. So whatever. Gottfried. Again, as they tell you here, we don't know much about these people, and this is really about love. -

Portland Daily Press: March 23,1886

DAILY PRESS. PORTLANDI. lil, f ——■—^ Libtnry CENTS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862—VOL. 23. PORTLAND, TUESDAY MORNING, MARCH 23, 1886. M.M PRICE THREE Mr» John D. Tilton of Hill has GORHAM. SPECIAL NOTICES. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, FROM WASHINGTON. BROADWAY SURFACE FRAUDS. THE PAN ELECTRIC. FOREIGN. Rocky rented the farm of Simon Mayberry In this Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the A Day of Interest with the COMPANY, March 22.—The examina- village, and will establish a milk route. Stephen- INSURANCE. PORTLAND PUBLISHING Mr. to be Washikotox, Germans and Jews Expelled from Dunn's Free Iron Ships Bill Alderman Jaehne Arraigned and of Dr. sons nnd AT 97 Exchange Street. Portlajtd, Me. tion of Casey Young was resumed beforo Memorial services on the death Descendants of the Long- Reported to the House. Held In Poland. Cross W.D. Address aB communications to sas.OOO. the telephone Investigating committee this Morgan, a high official in the Golden fellow Family. LITTLE & PORTLAND PUBLISHING OO. after the will soon be held the members of CO., afternoon. Young said that first order, by the kind 31 Through Invitation of Mr. Ste- EXCHANGE Mr. a directors of the An Conflict Between Troops the in this and Cumberland STREET, Dingley Wants the Free Material! How Public Spirited Woman Se* meeting of the board of Pan Open Commandery L. of KHiablishetl iu 1M.J. THE WEATHER. phen Stephenson Gorham, the writer Section a Bill. cured Electric when It had been agreed and Miners In Belgium. Mills village. Rsllable Insurance Reported in Separate Jaehne’s Confession. Company, Rioting was privileged to visit the old farm house against Flro or in first sold on Mr. -

Helping Your Students with Homework a Guide for Teachers

Helping Your Students With Homework A Guide for Teachers Helping Your StudentsWith Homework A Guide for Teachers By Nancy Paulu Edited by Linda B. DarbyIllustrated by Margaret Scott Office of Educational Research and Improvement U.S. Department of Education Foreword Homework practices vary widely. Some teachers make brilliant assignments that combine learning and pleasure. Others use homework as a routine to provide students with additional practice on important activities. And, unfortunately, some assign ©busyworkª that harms the educational process, by turning students offÅnot only making them feel that learning is not enjoyable or worthwhile, but that their teachers do not understand or care about them. Homework has long been a mainstay of American education for good reason: it extends time available for learning, and children who spend more time on homework, on average, do better in school. So how can teachers ease homework headaches? The ideas in this booklet are based on solid educational research. The information comes from a broad range of top-notch, experienced teachers. As you read through, you will find some familiar ideas, but may also find tips and assignments that suit your teaching needs and style. Students, teachers, and parents or caregivers all play vital roles in the homework process. I challenge you to contribute all you can to making homework meaningful and beneficial for your students. Peirce Hammond Director Office of Reform Assistance and Dissemination Contents Foreword ........................................................ iii Homework: A Concern for Teachers ...................................... 1 Hurdles to Homework ................................................. 2 Overcoming the Obstacles ............................................... 4 Tips for Getting Homework Done ........................................ 5 1. Lay out expectations early in the school year ..................... -

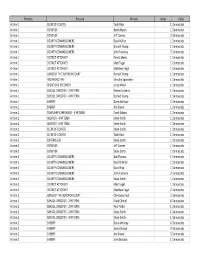

Livability Court Records 1/1/1997 to 8/31/2021

Livability Court Records 1/1/1997 to 8/31/2021 Last First Middle Case Charge Disposition Disposition Date Judge 133 Cannon St Llc Rep JohnCompany Q Florence U43958 Minimum Standards For Vacant StructuresGuilty 8/13/18 Molony 148 St Phillips St Assoc.Company U32949 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 10/17/11 Molony 18 Felix Llc Rep David BevonCompany U34794 Building Permits; Plat and Plans RequiredGuilty 8/13/18 Mendelsohn 258 Coming Street InvestmentCompany Llc Rep Donald Mitchum U42944 Public Nuisances Prohibited Guilty 12/18/17 Molony 276 King Street Llc C/O CompanyDiversified Corporate Services Int'l U45118 STR Failure to List Permit Number Guilty 2/25/19 Molony 60 And 60 1/2 Cannon St,Company Llc U33971 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony 60 Bull St Llc U31469 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony 70 Ashe St. Llc C/O StefanieCompany Lynn Huffer U45433 STR Failure to List Permit Number N/A 5/6/19 Molony 70 Ashe Street Llc C/O CompanyCobb Dill And Hammett U45425 STR Failure to List Permit Number N/A 5/6/19 Molony 78 Smith St. Llc C/O HarrisonCompany Malpass U45427 STR Failure to List Permit Number Guilty 3/25/19 Molony A Lkyon Art And Antiques U18167 Fail To Follow Putout Practices Guilty 1/22/04 Molony Aaron's Deli Rep Chad WalkesCompany U31773 False Alarms Guilty 9/14/16 Molony Abbott Harriet Caroline U79107 Loud & Unnecessary Noise Guilty 8/23/10 Molony Abdo David W U32943 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony Abdo David W U37109 Public Nuisances Prohibited Guilty 2/11/14 Pending Abkairian Sabina U41995 1st Offense - Failing to wear face coveringGuilty or mask. -

Write-In Results Primary 5-23-19 Municpal.Xlsx

Precinct Position WriteIn Votes Party Antrim 1 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Becky Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Jeff Conner 2 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Forest Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matt Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matthew Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 JUDGE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 PROTHONOTARY Timothy Sponseller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 REGISTER & RECORDER Linda Miller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 2 YR TERM Kristen Sutherin 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Dane Anthony 2 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Jim Brown 1 Democratic Antrim 1 TOWNSHIP SUPERVISOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Frank Adams 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CONTROLLER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Jeff Conner 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Bob Thomas 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David S Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Slye 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Steve Smith 1 Democratic -

A Feminist Rhetorical Critique of Zombie Apocalypse Television Narrative

Ohio Communication Journal Volume 52 – October 2014, pp. 64-74 The Walking (Gendered) Dead: A Feminist Rhetorical Critique of Zombie Apocalypse Television Narrative John Greene Michaela D.E. Meyer This essay presents a feminist rhetorical criticism of AMC’s The Walking Dead, exposing how hegemonic gender roles reinforce patriarchy within the series. We connect previous research on horror film and television, particularly in the zombie apocalypse genre, to representations of gender roles in popular culture. Our analysis reveals five categories of gendered representation: sexist rhetoric, division of labor, the role of protector, White male leadership, and the role of the dutiful wife. The Walking Dead narrative features women as incapable of surviving the apocalypse without men, renders them slaves to products of consumption (such as clothing), and ultimately strips them of autonomous decision making. We connect these images to the never-ending process of consumption and creation perpetuated by zombie narratives as representative of our social unease with capitalism, consumerism and its link to gendered identity. Over fifty years after George A. Romero forever changed the horror genre with Night of the Living Dead, 5.3 million viewers watched once again as the dead rose to devour the living in the series premiere of AMC’s The Walking Dead (AMC, 2010). The Walking Dead is one of the most-watched pieces of zombie fiction ever created, and is the first that has been successfully launched on cable television. Robert Kirkman, the creator of the graphic novel series on which the show is based, stated that “it’s something that succeeds in movies all the time, but I don’t think anybody has seen survival horror on TV before” (Stelter, 2010). -

An Ultra-Realist Analysis of the Walking Dead As Popular

CMC0010.1177/1741659017721277Crime, Media, CultureRaymen 721277research-article2017 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library Article Crime Media Culture 1 –19 Living in the end times through © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: popular culture: An ultra-realist sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017721277DOI: 10.1177/1741659017721277 analysis of The Walking Dead as journals.sagepub.com/home/cmc popular criminology Thomas Raymen Plymouth University, UK Abstract This article provides an ultra-realist analysis of AMC’s The Walking Dead as a form of ‘popular criminology’. It is argued here that dystopian fiction such as The Walking Dead offers an opportunity for a popular criminology to address what criminologists have described as our discipline’s aetiological crisis in theorizing harmful and violent subjectivities. The social relations, conditions and subjectivities displayed in dystopian fiction are in fact an exacerbation or extrapolation of our present norms, values and subjectivities, rather than a departure from them, and there are numerous real-world criminological parallels depicted within The Walking Dead’s postapocalyptic world. As such, the show possesses a hard kernel of Truth that is of significant utility in progressing criminological theories of violence and harmful subjectivity. The article therefore explores the ideological function of dystopian fiction as the fetishistic disavowal of the dark underbelly of liberal capitalism; and views the show as an example of the ultra-realist concepts of special liberty, the criminal undertaker and the pseudopacification process in action. In drawing on these cutting- edge criminological theories, it is argued that we can use criminological analyses of popular culture to provide incisive insights into the real-world relationship between violence and capitalism, and its proliferation of harmful subjectivities.