An Ultra-Realist Analysis of the Walking Dead As Popular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bond Basics: What Are Bonds?

Bond Basics: What Are Bonds? Have you ever borrowed money? Of course you have! Whether we hit our parents up for a few bucks to buy candy as children or asked the bank for a mortgage, most of us have borrowed money at some point in our lives. Just as people need money, so do companies and governments. A company needs funds to expand into new markets, while governments need money for everything from infrastructure to social programs. The problem large organizations run into is that they typically need far more money than the average bank can provide. The solution is to raise money by issuing bonds (or other debt instruments) to a public market. Thousands of investors then each lend a portion of the capital needed. Really, a bond is nothing more than a loan for which you are the lender. The organization that sells a bond is known as the issuer. You can think of a bond as an IOU given by a borrower (the issuer) to a lender (the investor). Of course, nobody would loan his or her hard-earned money for nothing. The issuer of a bond must pay the investor something extra for the privilege of using his or her money. This "extra" comes in the form of interest payments, which are made at a predetermined rate and schedule. The interest rate is often referred to as the coupon. The date on which the issuer has to repay the amount borrowed (known as face value) is called the maturity date. Bonds are known as fixed- income securities because you know the exact amount of cash you'll get back if you hold the security until maturity. -

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Government Bonds Have Given Us So Much a Roadmap For

GOVERNMENT QUARTERLY LETTER 2Q 2020 BONDS HAVE GIVEN US SO MUCH Do they have anything left to give? Ben Inker | Pages 1-8 A ROADMAP FOR NAVIGATING TODAY’S LOW INTEREST RATES Matt Kadnar | Pages 9-16 2Q 2020 GOVERNMENT QUARTERLY LETTER 2Q 2020 BONDS HAVE GIVEN US SO MUCH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Do they have anything left to give? The recent fall in cash and bond yields for those developed countries that still had Ben Inker | Head of Asset Allocation positive yields has left government bonds in a position where they cannot provide two of the basic investment services they When I was a student studying finance, I was taught that government bonds served have traditionally provided in portfolios – two basic functions in investment portfolios. They were there to generate income and 1 meaningful income and a hedge against provide a hedge in the event of a depression-like event. For the first 20 years or so an economic disaster. This leaves almost of my career, they did exactly that. While other fixed income instruments may have all investment portfolios with both a provided even more income, government bonds gave higher income than equities lower expected return and more risk in the and generated strong capital gains at those times when economically risky assets event of a depression-like event than they fell. For the last 10 years or so, the issue of their income became iffier. In the U.S., the used to have. There is no obvious simple income from a 10-Year Treasury Note spent the last decade bouncing around levels replacement for government bonds that similar to dividend yields from equities, and in most of the rest of the developed world provides those valuable investment government bond yields fell well below equity dividend yields. -

Chapter 06 - Bonds and Other Securities Section 6.2 - Bonds Bond - an Interest Bearing Security That Promises to Pay a Stated Amount of Money at Some Future Date(S)

Chapter 06 - Bonds and Other Securities Section 6.2 - Bonds Bond - an interest bearing security that promises to pay a stated amount of money at some future date(s). maturity date - date of promised final payment term - time between issue (beginning of bond) and maturity date callable bond - may be redeemed early at the discretion of the borrower putable bond - may be redeemed early at the discretion of the lender redemption date - date at which bond is completely paid off - it may be prior to or equal to the maturity date 6-1 Bond Types: Coupon bonds - borrower makes periodic payments (coupons) to lender until redemption at which time an additional redemption payment is also made - no periodic payments, redemption payment includes original loan principal plus all accumulated interest Convertible bonds - at a future date and under certain specified conditions the bond can be converted into common stock Other Securities: Preferred Stock - provides a fixed rate of return for an investment in the company. It provides ownership rather that indebtedness, but with restricted ownership privileges. It usually has no maturity date, but may be callable. The periodic payments are called dividends. Ranks below bonds but above common stock in security. Preferred stock is bought and sold at market price. 6-2 Common Stock - an ownership security without a fixed rate of return on the investment. Common stock dividends are paid only after interest has been paid on all indebtedness and on preferred stock. The dividend rate changes and is set by the Board of Directors. Common stock holders have true ownership and have voting rights for the Board of Directors, etc. -

3. VALUATION of BONDS and STOCK Investors Corporation

3. VALUATION OF BONDS AND STOCK Objectives: After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Understand the role of stocks and bonds in the financial markets. 2. Calculate value of a bond and a share of stock using proper formulas. 3.1 Acquisition of Capital Corporations, big and small, need capital to do their business. The investors provide the capital to a corporation. A company may need a new factory to manufacture its products, or an airline a few more planes to expand into new territory. The firm acquires the money needed to build the factory or to buy the new planes from investors. The investors, of course, want a return on their investment. Therefore, we may visualize the relationship between the corporation and the investors as follows: Capital Investors Corporation Return on investment Fig. 3.1: The relationship between the investors and a corporation. Capital comes in two forms: debt capital and equity capital. To raise debt capital the companies sell bonds to the public, and to raise equity capital the corporation sells the stock of the company. Both stock and bonds are financial instruments and they have a certain intrinsic value. Instead of selling directly to the public, a corporation usually sells its stock and bonds through an intermediary. An investment bank acts as an agent between the corporation and the public. Also known as underwriters, they raise the capital for a firm and charge a fee for their services. The underwriters may sell $100 million worth of bonds to the public, but deliver only $95 million to the issuing corporation. -

Protest and State–Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

SIPRI Policy Paper PROTEST AND STATE– 56 SOCIETY RELATIONS IN October 2020 THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Ambassador Ramtane Lamamra (Algeria) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Protest and State– Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa SIPRI Policy Paper No. 56 dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil October 2020 © SIPRI 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 Figure 1.1. Classification of countries in the Middle East and North Africa by 2 protest intensity 2. State–society relations in the Middle East and North Africa 5 Mass protests 5 Sporadic protests 16 Scarce protests 31 Highly suppressed protests 37 Figure 2.1. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

The Walking Dead Chop Shop Jay Chiat Awards Category: National Strategy

HYUNDAI: THE WALKING DEAD CHOP SHOP JAY CHIAT AWARDS CATEGORY: NATIONAL STRATEGY BACKGROUND Hyundai has been on the rise with sales increasing by 89% from 2009–2012.1 The brand had built a solid reputation as a rational choice among average car shoppers. But among the highly desirable youth audience driven more by their interests and passions, reason alone wasn’t enough to get them excited about the Hyundai brand. 1Source: Experian Retail Registration 2009 – 2013; 2Source: GfK Quarterly Brand Tracking Studies 2013 Involve the Fans vs. Interrupting Them In the fall of 2013, Hyundai had product placement in the second season of The Walking Dead TV show as a way to build relevance among the show’s Gen Y audience. As the popularity of zombie culture grew, we decided to elevate the partnership with The Walking Dead to increase our relevance with this growing and passionate millennial fan base. However, this highly engaged and passionate Walking Dead youth fanbase didn’t want a brand to interrupt and commercialize their beloved show. So how do you make a rational car brand appealing to an emotionally driven fan audience? Our challenge was to involve the fans with the Hyundai brand and its cars in an authentic way that added value to their experience of The Walking Dead, and not interrupt them. OBJECTIVES & SUCCESS METRICS If we were going to involve the fans, we knew we had to motivate them to participate with us and eventually inspire them to help spread the word on behalf of the brand. OBJECTIVE #1: Engage the Fans to BUILD Demonstrate that the audience is spending more time participating with the Hyundai brand through the number of vehicles configured and built. -

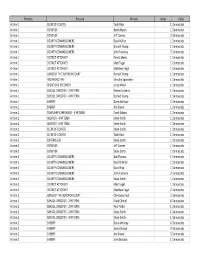

The Late Registrations and Corrections to Greene County Birth Records

Index for Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives The late registrations and corrections to Greene County birth records currently held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives were recorded between 1940 and 1991, and include births as early as 1862 and as late as 1989. These records represent the effort of county government to correct the problem of births that had either not been recorded or were not recorded correctly. Often times the applicant needed proof of birth to obtain employment, join the military, or draw on social security benefits. An index of the currently available microfilmed records was prepared in 1989, and some years later, a supplemental index of additional records held by Greene County was prepared. In 2011, several boxes of Probate Court documents containing original applications and backup evidence in support of the late registrations and corrections to the birth records were sorted and processed for archival storage. This new index includes and integrates all the bound and unbound volumes of late registrations and corrections of birth records, and the boxes of additional documents held in the Greene County Archives. The index allows researchers to view a list arranged in alphabetical order by the applicant’s last name. It shows where the official record is (volume and page number) and if there is backup evidence on file (box and file number). A separate listing is arranged alphabetically by mother’s maiden name so that researchers can locate relatives of female relations. Following are listed some of the reasons why researchers should look at the Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records: 1. -

The Biden Administration and the Middle East: Policy Recommendations for a Sustainable Way Forward

THE BIDEN ADMINISTRATION AND THE MIDDLE EAST: POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A SUSTAINABLE WAY FORWARD THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE MARCH 2021 WWW.MEI.EDU 2 The Biden Administration and the Middle East: Policy Recommendations for a Sustainable Way Forward The Middle East Institute March 2021 3 CONTENTS FOREWORD Iraq 21 Strategic Considerations for Middle East Policy 6 Randa Slim, Senior Fellow and Director of Conflict Paul Salem, President Resolution and Track II Dialogues Program Gerald Feierstein, Senior Vice President Ross Harrison, Senior Fellow and Director of Research Israel 23 Eran Etzion, Non-Resident Scholar POLICY BRIEFS Jordan 26 Dima Toukan, Non-Resident Scholar Countries/Regions Paul Salem, President US General Middle East Interests & Policy Priorities 12 Paul Salem, President Lebanon 28 Christophe Abi-Nassif, Director of Lebanon Program Afghanistan 14 Marvin G. Weinbaum, Director of Afghanistan and Libya 30 Pakistan Program Jonathan M. Winer, Non-Resident Scholar Algeria 15 Morocco 32 Robert Ford, Senior Fellow William Lawrence, Contributor Egypt 16 Pakistan 34 Mirette F. Mabrouk, Senior Fellow and Director of Marvin G. Weinbaum, Director of Afghanistan and Egypt Program Pakistan Program Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) 18 Palestine & the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process 35 Gerald Feierstein, Senior Vice President Nathan Stock, Non-Resident Scholar Khaled Elgindy, Senior Fellow and Director of Program Horn of Africa & Red Sea Basin 19 on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli Affairs David Shinn, Non-Resident Scholar Saudi Arabia 37 Iran -

Write-In Results Primary 5-23-19 Municpal.Xlsx

Precinct Position WriteIn Votes Party Antrim 1 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Becky Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Jeff Conner 2 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Forest Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matt Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matthew Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 JUDGE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 PROTHONOTARY Timothy Sponseller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 REGISTER & RECORDER Linda Miller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 2 YR TERM Kristen Sutherin 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Dane Anthony 2 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Jim Brown 1 Democratic Antrim 1 TOWNSHIP SUPERVISOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Frank Adams 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CONTROLLER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Jeff Conner 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Bob Thomas 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David S Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Slye 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Steve Smith 1 Democratic -

557. Small-Screen Souths: Interrogating the Televisual Archive 1:45-3:00 P.M., 114 VCC West

557. Small-Screen Souths: Interrogating the Televisual Archive 1:45-3:00 p.m., 114 VCC West Program arranged by the Society for the Study of Southern Literature. Presiding: Gina Caison, Georgia State Univ. 1. “Mid-Century Transition: Lost Boundaries and Early Television,” Robert A. Jackson, Univ. of Tulsa Abstract: “We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners,” declared Martin Luther King, Jr. in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965. “We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television.” Yet the relationship between television and the American civil rights struggle dates back well before the most iconic images of the movement—white mobs, police dogs, fire hoses; defiant segregationist politicians railing against “outside agitators”; and King himself—of the late 1950s and 1960s. Indeed, early television was the site of contested visions of race, anticipating the long-familiar television/civil rights collaboration, in important, if less famous, ways. My paper will consider Lost Boundaries (1949), one of several post-World War II “social problem” films addressing racism. When censorship authorities in Memphis and Atlanta banned the film to prevent its theatrical exhibition, producer Louis de Rochemont attempted to buy time to air the Lost Boundaries on those cities’ television stations, over which municipal film censors had no legal authority. Thus, to some observers of this and other contemporary episodes, television at midcentury represented a new frontier in the history of the mediation of race, leading Ebony magazine to state as early as 1950 that “television is free of racial barriers.” The case of Lost Boundaries in the South, where authorities responded to de Rochemont’s surprising move with bewilderment and suspicion, reveals both the possibilities for progress and the institutional complexity of the postwar transition from the old studio model of theatrical exhibition to an emerging regime of televised programming in the private domestic realm.