557. Small-Screen Souths: Interrogating the Televisual Archive 1:45-3:00 P.M., 114 VCC West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

The Late Registrations and Corrections to Greene County Birth Records

Index for Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives The late registrations and corrections to Greene County birth records currently held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives were recorded between 1940 and 1991, and include births as early as 1862 and as late as 1989. These records represent the effort of county government to correct the problem of births that had either not been recorded or were not recorded correctly. Often times the applicant needed proof of birth to obtain employment, join the military, or draw on social security benefits. An index of the currently available microfilmed records was prepared in 1989, and some years later, a supplemental index of additional records held by Greene County was prepared. In 2011, several boxes of Probate Court documents containing original applications and backup evidence in support of the late registrations and corrections to the birth records were sorted and processed for archival storage. This new index includes and integrates all the bound and unbound volumes of late registrations and corrections of birth records, and the boxes of additional documents held in the Greene County Archives. The index allows researchers to view a list arranged in alphabetical order by the applicant’s last name. It shows where the official record is (volume and page number) and if there is backup evidence on file (box and file number). A separate listing is arranged alphabetically by mother’s maiden name so that researchers can locate relatives of female relations. Following are listed some of the reasons why researchers should look at the Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records: 1. -

An Ultra-Realist Analysis of the Walking Dead As Popular

CMC0010.1177/1741659017721277Crime, Media, CultureRaymen 721277research-article2017 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library Article Crime Media Culture 1 –19 Living in the end times through © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: popular culture: An ultra-realist sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017721277DOI: 10.1177/1741659017721277 analysis of The Walking Dead as journals.sagepub.com/home/cmc popular criminology Thomas Raymen Plymouth University, UK Abstract This article provides an ultra-realist analysis of AMC’s The Walking Dead as a form of ‘popular criminology’. It is argued here that dystopian fiction such as The Walking Dead offers an opportunity for a popular criminology to address what criminologists have described as our discipline’s aetiological crisis in theorizing harmful and violent subjectivities. The social relations, conditions and subjectivities displayed in dystopian fiction are in fact an exacerbation or extrapolation of our present norms, values and subjectivities, rather than a departure from them, and there are numerous real-world criminological parallels depicted within The Walking Dead’s postapocalyptic world. As such, the show possesses a hard kernel of Truth that is of significant utility in progressing criminological theories of violence and harmful subjectivity. The article therefore explores the ideological function of dystopian fiction as the fetishistic disavowal of the dark underbelly of liberal capitalism; and views the show as an example of the ultra-realist concepts of special liberty, the criminal undertaker and the pseudopacification process in action. In drawing on these cutting- edge criminological theories, it is argued that we can use criminological analyses of popular culture to provide incisive insights into the real-world relationship between violence and capitalism, and its proliferation of harmful subjectivities. -

Teachers' Notes Media Studies

Media Studies - TV Television in the Global Age -Teachers’ Notes • The resources are intended to support teachers delivering the new AS/A Level specification. They have been created based on the assumption that many teachers will already have some experience of Media Studies teaching and therefore the notes have been pitched at a level which takes this into consideration. Other resources which outline e.g. technical and visual codes, and how to apply these, are readily available. • There is an overlap between the different areas of the theoretical framework and the various contexts, and a ‘text-out’ teaching structure may offer opportunities for a more holistic approach. • Slides are adaptable to use with your students. Explanatory notes for teachers/suggestions for teaching are in the Teachers’ Notes. • The resources are intended to offer guidance only and are by no means exhaustive. It is expected that teachers will subsequently research and use their own materials and teaching strategies within their delivery. • Television as an industry has changed dramatically since its inception. • Digital technologies and other external factors have led to changes in production, distribution, the increasingly global nature of television and the ways in which audiences consume texts. • It is expected that students will require teacher-led delivery which outlines these changes, but the focus of delivery will differ dependent on the text chosen. Media Studies - TV 1 Media Studies - TV Television in the Global Age -Teachers’ Notes The Returned/Les Revenants Episode Suggestions Series 1: Episode 1 is the ‘set’ text but you may also want to look at other episodes, including Episode 8 for the denouement of the first series. -

082618 Bulletin

Diocese of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands 42 Barren Spot - P.O. Box 1160 Kings Hill U.S. Virgin Islands 00851 Tel. (340) 778-0484 Fax. (340) 779-3151 Website: www.catholicvi.com/stann/ E-mail: [email protected] Twenty-first Sunday In O. T. —Year B Fr. Louis Kemayou, Pastor August 25-26, 2018 Most Rev. Herbert A. Bevard Jesus said: “Do you also want to leave?” Simon Peter answered: “Master to whom shall we go?” SANCTUARY DEVOTIONAL LIGHT ALTAR FLOWERS Would you like to donate the sanctuary candle in Would you like the altar flowers to be offered in memory of someone or in celebration of a special memory of someone or in celebration of a special occasion, please call the office and schedule a occasion, Please call the office and schedule a date. A free-will donation is welcome. date. A free-will donation is welcome. ST. ANN’S BOOKSTORE & GIFTS SHOP CCN / EWTN Channel 7 Tuesdays to Fridays: 9:00 a.m.– 3:00 p.m. 9:30 a.m. Sundays Mass (Live) Channel 7 Sundays: Open after Masses Internet: www.livestream.com/ caribbeancatholicnetwork7 “TOGETHER BUILDING THE KINGDOM OF GOD.” Directory PRIESTS DEACONS Rev. Fr. Louis K. Kemayou, Pastor Rev. Mr. Joseph T. Mark, OCDS Rev. Msgr. Michael F. Kosak, (Retired) In Residence Rev. Mr. Hyacinthe George, Rev. Mr. Denis Griffith, SECRETARY Mrs. Linda O’Neale Rev. Mr. Edward Cave, Rev. Mr. Norbert Xavier, Bookstore: Office Staff Rev. Mr. Eugene Thompson, ( Retired ) RELIGIOUS EDUCATION: Mrs. Patricia Browne, Coordinator Rev. Mr. Arnold Helenese, OCDS– ( Retired ) MAINTENANCE: Mr. -

Press™ Kit 01 Contents

NO SAFE HARBOUR ™ SEASON TWO ® ® PRESS™ KIT 01 CONTENTS 03 SYNOPSIS 04 CAST & CHARACTERS 23 PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES 28 INTERVIEW: DAVE ERICKSON EXECUTIVE PRODUCER & SHOWRUNNER 31 PRODUCTION CREDITS ® ™ SYNOPSIS Last season, Fear the Walking Dead explored a blended family who watched a burning, dead city as they traversed a devastated Los Angeles. In season two, the group aboard the ‘Abigail’ is unaware of the true breadth and depth of the apocalypse that surrounds them; they assume there is still a chance that some city, state, or nation might be unaffected - some place that the Infection has not reached. But as Operation Cobalt goes into full effect, the military bombs the Southland to cleanse it of the Infected, driving the Dead toward the sea. As Madison, Travis, Daniel, and their grieving families head for ports unknown, they will discover that the water may be no safer than land. ® ™ 03 CAST & CHARACTERS ® ™ 04 MADISON CLARK In many ways, the Madison of season two is the same woman we met in the pilot - a leader, a moral compass - but in a whole new devastated, apocalyptic world. As the season plays out, Madison will be faced with a world that often has no room for empathy or compassion. Forced to navigate a deceptive and manipulative chart of personalities, Madison’s success in this new world is predicated on understanding that, at the end of the world, lending a helping hand can often endanger those you love. She may maintain her maternal ferocity, but the apocalypse will force her to make decisions and sacrifices that could break even the strongest people. -

Press Kit Contents Synopsis 3 Cast & Characters 4 Production Biographies 31

SEASON THREE PRESS KIT CONTENTS SYNOPSIS 3 CAST & CHARACTERS 4 PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES 31 2 S Y N O PS I S As “Fear the Walking Dead” returns for season three, our families will be brought together in the vibrant and violent ecotone of the US-Mexico border. International lines done away with following the world’s end, our characters must attempt to rebuild not only society, but family as well. Madison has reconnected with Travis but Alicia has been fractured by her murder of Andres. Mere miles from his mother, Nick’s first action as a leader saw Luciana ambushed by an American militia group – the couple escaped death but Nick no longer feels immortal. Recovering both emotionally and physically, Strand has his sights set on harnessing the new world’s currency, and Ofelia’s captivity will test her ability to survive and see if she can muster the savagery of her father. 3 CAST + CHARACTERS 4 4 MADISON CLARK (Kim Dickens) “The devil you know…” In season three, Madison moves beyond mercy. She promises herself never to repeat the mistakes of the past. If that means she must embrace brutality, so be it. As Madison evolves over the course of this season, we will see her turn even darker. Her ends are pure, but her means are morally compromised. She will sacrifice compassion – and she will risk those she holds most dear. In pursuit of Nick, Madison leads Travis and Alicia through the aftermath of the battle that ended season two – a fight that could have taken Nick and Luciana’s lives. -

Department of Behavioral Health FY19-20 Performance Oversight Questions

Department of Behavioral Health FY19-20 Performance Oversight Questions COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COMMITTEE ON HEALTH CHAIRMAN VINCENT C. GRAY COUNCILMEMBER, WARD 7 Department of Behavioral Health Oversight Questions 1. Please provide a current organizational chart for DBH. Please provide information to the activity level. In addition, please identify the number of full time equivalents (FTEs) at each organizational level and the employee responsible for the management of each program and activity. If applicable, please provide a narrative explanation of any organizational changes made during FY19 and to date in FY20. 2. Please provide the following budget information for DBH, including the amount budgeted and actually spent for FY19 and to date in FY20. In addition, please describe any variance between the amount budgeted and actually spent for FY19 and to date in FY20: - At the agency level, please provide information broken out by source of funds and by Comptroller Source Group and Comptroller Object; - At the program level, please provide the information broken out by source of funds and by Comptroller Source Group and Comptroller Object; and, - At the activity level, please provide the information broken out by source of funds and by Comptroller Source Group. 3. Please provide a complete accounting of all intra-district transfers received by or transferred from DBH during FY19 and to date in FY20. For each, please provide a narrative description as to the purpose of the transfer and which programs, activities, and services within DBH the transfer affected. 4. Please provide a complete accounting of all reprogramings received by or transferred from DBH in FY19 and to date in FY20. -

Commutations Granted by President Barack Obama (2009-2017) | PARDON | Department of Justice

Commutations Granted by President Barack Obama (2009-2017) | PARDON | Department of Justice HOME ABOUT AGENCIES RESOURCES NEWS CAREERS CONTACT Home » Office of the Pardon Attorney » Clemency Recipients SHARE Home About the Office COMMUTATIONS GRANTED BY PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA (2009-2017) Meet the Pardon Attorney Search All Pardons and Commutations Frequently Asked Questions Search Pending January 19, 2017 | January 17, 2017 | December 19, 2016 | November 22, 2016 | November 4, 2016 | October 27, 2016 | October 6, 2016 Clemency Case Files | August 30, 2016 | August 3, 2016 | June 3, 2016 | May 5, 2016 | March 30, 2016 | January 16, 2016 | December 18, 2015 | July 13, 2015 | March 31, 2015 | December 17, 2014 | December 15, 2014 | April 15, 2014 | December 19, 2013 | November 21, 2011 Legal Authority Governing Executive JANUARY 19, 2017 Clemency Download PDF Clemency Warrant Policies Clemency Forms & Abdulmuntaqim Ad-Deen Instructions Standards for Offense: Possession with intent to distribute cocaine base Consideration of Clemency Petitions District/Date: District of Maryland; October 8, 2008 Clemency Statistics Sentence: 235 months' imprisonment; five years' supervised release Clemency Recipients Terms of grant: Prison sentence commuted to a term of 180 months' imprisonment, conditioned upon enrollment in residential drug Pardons Granted by treatment President Donald Trump Lesly Alexis Commutations Granted by Offense: Conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute more than five kilograms of cocaine powder and more than 50 grams President Donald of cocaine base Trump Pardons Granted by District/Date: Northern District of Florida; July 29, 2003 President Barack Obama Sentence: 384 months' imprisonment; five years' supervised release; $1,000 fine Commutations Terms of grant: Prison sentence commuted to a term of 262 months' imprisonment Granted by President Barack Obama Gary J. -

The Significance of the Wasteland in American Culture

Berkeley Undergraduate Journal 160 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE WASTELAND IN AMERICAN CULTURE By Joshua Peterson n this paper, I examine the sense of restlessness and the resultant apocalyptic fantasy in contem- porary American culture by distilling two film genres—the Hollywood western and the post- apocalyptic—down to their basic structural elements. The post-apocalyptic genre’s aesthetic Iand thematic borrowing from the Hollywood western signifies a cynical critique of the frontier myth. In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner presented The Significance of the Frontier in American His- tory, his “Frontier Thesis,” which mourns the closure of the frontier and celebrates the American institutions built upon it.1 The frontier only exists insofar as it is available for human exploration and settlement. Though the frontier is long gone, the desire for open space and freedom from social restriction remains prominent in American culture. The post-apocalyptic genre continues Turner’s mourning and indulges the fantasy of free and open space. In essence, it gives the frontier back to viewers by undoing everything that the frontier made possible. The characters in the post- apocalyptic genre then explore the possibilities of rebuilding society and struggle (and often fail) to avoid the mistakes of America’s historical past. In this sense, the wasteland functions as a revision of the frontier myth. This paper explores the post-apocalyptic genre’s view of the frontier myth as a trajectory towards civilization’s collapse. It posits a more cynical view of humanity and, in doing so, aims to expose the feet of clay on which our social order stands. -

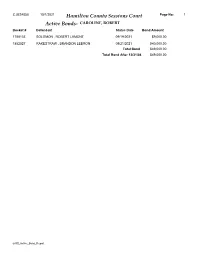

Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount

CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 1 Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1788133 SOLOMON , ROBERT LAMONT 09/19/2021 $9,000.00 1852527 RAKESTRAW , BRANDON LEBRON 09/21/2021 $40,000.00 Total Bond $49,000.00 Total Bond After 12/31/04 $49,000.00 arGS_Active_Bond_Report CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 2 Active Bonds- A BONDING COMPANY Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1768727 LEE , KAITLIN M 06/30/2019 $12,500.00 1792502 WAY , JASON J 01/11/2020 $3,000.00 1796727 FERRY , MATTHEW BRIAN 02/21/2020 $2,500.00 1804712 VILLANUEVA , ADAM LOUIS 05/25/2020 $3,000.00 1809034 SINFUEGO , NARCIAN LYNET 07/12/2020 $2,000.00 1817402 PETER , DALE NEIL 08/14/2021 $0.00 1830111 HAZLETON , SAMUEL T 02/14/2021 $2,000.00 1830122 HILL , JARED LEVI 02/14/2021 $500.00 1831701 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $5,000.00 1831702 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $2,000.00 1835471 SHROPSHIRE , EDWARD LEBRON 04/06/2021 $1,500.00 1839064 CHESNUTT , ALAN ARNOLD 05/06/2021 $2,500.00 1839968 SAARINEN , NICHOLAS AARRE 05/15/2021 $1,500.00 1844159 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $3,000.00 1844160 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $2,000.00 1844161 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1844162 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1846317 SMALL II, AARON CLAY 07/20/2021 $2,000.00 1846876 GIARDINA , MICHAEL N 07/24/2021 $3,000.00 1847003 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,500.00 1847004 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,000.00 1847006 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $500.00 1847417 -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H.