AN AQUEOUS TERRITORY This Page Intentionally Left Blank an AQUEOUS TERRITORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Historical Quarterly FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The Florida Historical Quarterly FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY V OLUME XLV July 1966 - April 1967 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XLV Abernethy, Thomas P., The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815- 1828, reviewed, 180 Adams, Adam, book review by, 70 Agriculture and the Civil War, by Gates, reviewed, 68 Alachua County Historical Commission, 89, 196 Alexander, Charles C., book review by, 186 “American Seizure of Amelia Island,” by Richard G. Lowe, 18 Annual Meeting, Florida Historical Society May 5-7, 1966, 199 May 5-6, 1967, 434 Antiquities Commission, 321 Appalachicola Historical Society, 308 Arana, Luis R., book review by, 61 Atticus Greene Haygood, by Mann, reviewed, 185 Bailey, Kenneth K., Southern White Protestantism in the Twen- tieth Century, reviewed, 80 Barber, Willard F., book review by, 84 Baringer, William E., book review by, 182 Barry College, 314 Batista, Fulgencio, The Growth and Decline of the Cuban Repub- lic, reviewed, 82 Battle of Pensacola, March 9 to May 8, 1781; Spain’s Final Triumph Over Great Britain in the Gulf of Mexico, by Rush, reviewed, 412 Beals, Carlton, War Within a War: The Confederacy Against Itself, reviewed, 182 Bearss, Edwin C., “The Federal Expedition Against Saint Marks Ends at Natural Bridge,” 369 Beck, Earl R., On Teaching History in Colleges and Universities, reviewed, 432 Bennett, Charles E., “Early History of the Cross-Florida Barge Canal,” 132; “A Footnote on Rene Laudionniere,” 287; Papers, 437 Bigelow, Gordon E., Frontier Eden: The Literary Career of Mar- jorie Kinnan Rawlings, reviewed, 410 “Billy Bowlegs (Holata Micco) in the Second Seminole War” (Part I), 219; “Billy Bowlegs (Holata Micco) in the Civil War” (Part II), 391 “Bishop Michael J. -

Simón Bolívar

Reading Comprehension/Biography SIMÓN BOLÍVAR Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios, (July 24, 1783 – December 17, 1830), more commonly known as Símon Bolívar, was one of the most important leaders of Spanish America's successful struggle for independence from Spain. He is a very important figure in South American political history, and served as President of Gran Colombia from 1821 to 1830, President of Peru from 1824 to 1826, and President of Bolivia from 1825 to 1826. Bolívar was born into a wealthy family in Caracas, in what is now Venezuela. Much of his family’s wealth came from silver, gold and copper mines. Later in his revolutionary life, Bolívar used part of the mineral income to finance the South American revolutionary wars. After the death of his parents, he went to Spain in 1799 to complete his education. He married there in 1802, but his wife died of yellow fever on a short return visit to Venezuela in 1803. Bolívar returned to Europe in 1804 and for a time was part of Napoleon's retinue. Bolívar returned to Venezuela in 1807, and, when Napoleon made Joseph Bonaparte King of Spain and its colonies in 1808, he participated in the resistance juntas in South America. The Caracas junta declared its independence in 1810, and Bolívar was sent to Britain on a diplomatic mission. Bolívar returned to Venezuela in 1811. In March 1812, he left Venezuela after an earthquake destroyed Caracas. In July 1812, junta leader Francisco de Miranda surrendered to the Spanish, and Bolívar had to flee. -

''All We Have Done, We Have Done for Freedom'': the Creole Slave-Ship Revolt (1841) and the Revolutionary Atlantic

IRSH 58 (2013), Special Issue, pp. 253–277 doi:10.1017/S0020859013000254 r 2013 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis ‘‘All We Have Done, We Have Done for Freedom’’: The Creole Slave-Ship Revolt (1841) and the Revolutionary Atlantic A NITA R UPPRECHT School of Humanities, University of Brighton 10–11 Pavilion Parade, Brighton, East Sussex BN1 1RA, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The revolt aboard the American slaving ship the Creole (1841) was an unprecedented success. A minority of the 135 captive African Americans aboard seized the vessel as it sailed from Norfolk, Virginia, to the New Orleans slave markets. They forced the crew to sail to the Bahamas, where they claimed their freedom. Building on previous studies of the Creole, this article argues that the revolt succeeded due to the circulation of radical struggle. Condensed in collective memory, political solidarity, and active protest and resistance, this circulation breached the boundaries between land and ocean, and gave shape to the revolu- tionary Atlantic. These mutineers achieved their ultimate aim of freedom due to their own prior experiences of resistance, their preparedness to risk death in violent insurrection, and because they sailed into a Bahamian context in which black Atlantic cooperation from below forced the British to serve the letter of their own law. When news of the extraordinary success of the slave revolt aboard the Creole broke in 1841, it was hailed as another Amistad. On 7 November the American slaving brig, having left Norfolk, Virginia, sailed into Nassau with 135 self-emancipated African Americans aboard. -

CQG Library Catalog TITLE

SUBJECT TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECT 2 ANNOT. PUB. DATE DB NOTES Oversize 100 Best Full-Size Quilt Blocks & Borders Dobbs, Phyllis, et al Publications 2005 International Home Dec 100 Quick-to-Quilt Potholders Stauffer, Jeanne, ed. Applique blocks House of White 2004 Pieced 101 Fabulous Rotary-Cut Quilts Hopkins, Judy MartingaleBirches 1998 Martin, Nancy J Foundation- 101 Foundation-Pieced Quilt Blocks: With Causee, Linda ASN 1996 Piecing Full-Size Patterns Foundation- 101 Log Cabin Blocks: With Full-Sized Causee, Linda ASN 1997 Piecing Patterns Pieced 101 Nine Patch Quilts Mitchell, Marti Applique ASN 2000 pgs. 19-46 loose Home Dec 101 Patchwork Potholders Causee, Linda blocks ASN 1997 Children 150 Blocks for Baby Quilts: Mix & Match Briscoe, Susan Applique, alphabet, C&T 2007 Designs for Cute & Cozy Quilted Foundation- numbers Applique 24Treasures Blossom Blocks to Applique Boerens, Trice Piecing embroidery Annie's 2006 glossary Folk/ Cottage 25 Years of Quilts: My 25 Favorites-New Mumm, Debbie Leisure Arts 2011 7/16 Looks & Better Than Ever Design 3 Dimensional Design Pasquini, Katie Art C&T 1988 2/18 Foundation- 300 Paper-Pieced Quilt Blocks Doak, Carol Holiday, Kids TPP 2004 signed, CD Piecing Holiday 301 Country Christmas Quilt Blocks Saffiote, Cheri Folk Sterling 2002 Oversize 365 Foundation Quilt Blocks Causee, Linda Foundation- Sterling 2005 2/17 Piecing Pieced 40 Fabulous Quick-Cut Quilts Sloppy, Evelyn Martingale 2005 Easy 9-Patch Pizzazz: Fast, Fun & Finished in Sisneros, Judy Applique, Art C&T 2006 signed a Day Pieced ABCD Quilts: -

EL INICIO DE LAS NEGOCIACIONES ENTRE ESPAÑA Y LOS NUEVOS ESTADOS AMERICANOS: LA MISIÓN DE MARIANO MONTILLA (1834) Orlando Arciniegas Duarte (Universidad De Alcalá)

EHSEA,N' 14/Enuro^uño 1997, pp. 735-150 EL INICIO DE LAS NEGOCIACIONES ENTRE ESPAÑA Y LOS NUEVOS ESTADOS AMERICANOS: LA MISIÓN DE MARIANO MONTILLA (1834) Orlando Arciniegas Duarte (Universidad de Alcalá) RESUMEN Tras la muerte de Fernando VII, las antiguas provincias americanas, constituidas en nuevos Estados, retomaron su propósito de verse reconocidas por la antigua metrópoli. El primer país en enviar comisionados fue Venezuela en 1834. De esa misión sería designado responsable el general Mariano Montilla, quien, tras algunas gestiones hubo de interrumpir su misión, pero cuyas aproximaciones al Gobierno español prepararon las importantes negociaciones cumpjidas por el también general Carlos Soublette. ABSTRACT Venezuelan General Mariano Montilla was designad in 1834 to undertake negotiations with Spain in order to earn political and institutional recognition for the new born state. Although this first mission had to be interrumpted, it set the basis for later and important agreements. Como es sabido, los cambios políticos que tomarían lugar en España tras la muerte de Fernando Vil alentarían a las ex colonias españolas, constituidas en nuevos Estados, a propiciar la búsqueda de su reconocimiento. Con cierta prontitud, algunos Gobiernos americanos, informados de la buena disposición del nuevo Gobierno liberal español, procedieron a autorizar comisionados que tanteasen la nueva coyuntura. Se sabía que España dejaría atrás la política de negar los reconocimientos, pero se desconocían las condiciones de negociación. Primero, Venezuela y México, que había sufrido intentos de reconquista, y un poco después Chile y Ecuador, serían los adelantados en enviar representantes suyos a Madrid, con el propósito de negociar tratados de reconocimiento y comercio. -

The Rites of Statehood: Violence and Sovereignty in Spanish America, 1789-1821 Jeremy Adelman Princeton University in Gabriel Ga

1 The Rites of Statehood: Violence and Sovereignty in Spanish America, 1789-1821 Jeremy Adelman Princeton University In Gabriel Garcia Marquez's novel, The General in his Labyrinth, a long-winded Frenchman lectures a pensive, dying Simon Bolivar. The Liberator responds. He acknowledges that the revolution unleashed the furies of avenging justice, and laments, without repudiating, his decision to order the execution of eight hundred Spanish prisoners in a single day, including pa.ti~nts in La Guaira' s moral authority to reproach me, for if any history is drowned in blood, indignity, and injustice, it is the history of Europe." When the Frenchman tries to interrupt, Bolivar puts down his cutlery \ and glares at his guest. "Damn it, please let us have our Middle Ages in peace!" he exclaimed. 1 These, of course, were Garc,a Marquez's words, not Bolivar's. But they echo Bolivar's requiem on the events he shaped about the relationship between savagery and state-formation. More than lofty proclamations or principle's of statehood, the historical memory of the years leading to 1821 are saturated with blood. For the chroniclers and epic writers, from Jose Manuel, Restrepo's (1827) Historia de la Revolucion de Colombi~ to Garcia Marquez, the scenes of violence and carnage gave rise to narratives of sacrifice and struggle that could not be wholly redeemed by what came after. And yet, we have not thought very systematically about the significance of political violence in Latin America - despite its recurrence. Perhaps it is because of its recurrence: for so many, the cruelty was sown into a ''tradition'' of conquest and 1 Gabriel Garda Marquez, The General in His Labyrinth (New York: Knopf, 1990), p. -

View the Full Report Here

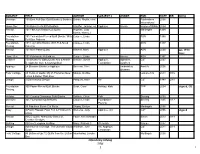

Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. Definition of Terms 5 2. Introduction 6 3. Functions of the Commission 7 4. Composition of the Commission 8 5. Staff of the Commission 11 6. Activities of the Commission 12 7. Projected and Actual Expenditure of the Court and Commission 14 8. Appointment and Inauguration of New President of the Court 15 9. Interaction with the Trustees and the Trust Fund 16 10. Matters of Note 17 11. Appreciation of Former Chairman 18 12. In Memoriam 21 13. Feature on Guyana 22 14. Snapshots of 2011 26 Appendices: Appendix A: Meetings of the Commission in 2011 27 Appendix B: Attendance of Members at Meetings of the Commission in 2011 27 Appendix C: Meetings of Committees of the Commission in 2011 28 Appendix D: Members of Committees of the Commission in 2011 29 Appendix E: Audited Financial Statements of the Commission 30 for the year ended December 31, 2011 Page 3 Seated L-R: Professor Harold Lutchman, B.Sc., M.Sc., LL.B., Ph.D.; Mr. Jefferson Cumberbatch, LL.B.; the Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Dennis Byron; Dr. Joseph Archibald, Q.C.; Dr. the Hon. Lloyd Barnett, O.J. Standing L-R: Sir Fred Gollop, K.A., Q.C.; Mr. Martin Daly, S.C.; the Hon. Mr. Justice Hugh A. Rawlins; Mr. Emile Ferdinand, LL.B., LL.M.; Ambassador Wendell Lawrence, B.Sc., M.Sc., C.P.A.; Mr. Egbert Lionel, B.Sc., M.A. Page 4 1. DEFINITION OF TERMS In this Report the following terms which are frequently used have the meanings assigned to them below: “the Agreement” means the Agreement Establishing the Caribbean Court of Justice; “the Commission” means the Regional Judicial and Legal Services Commission; “the Court” means the Caribbean Court of Justice; “OECS” means the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States; “the Treaty” means the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas; “the Trustees” means the Board of Trustees of the Trust Fund; “the Trust Fund” means the Caribbean Court of Justice Trust Fund established by the Revised Agreement dated January 12, 2004. -

El Rey Ante El Tribunal De La Revolución: Nueva Granada 1808-1819*

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/hys.n31.55457 El rey ante el tribunal de la revolución: Nueva Granada 1808-1819* Isidro Vanegas Useche** Resumen El rey fue un actor central de las conmociones revolucionarias modernas. También lo fue en la Revolución neogranadina de la década de 1810, que vio cómo pasó de ser el núcleo del orden en su calidad de detentador y garante del poder y la autoridad, a convertirse en una figura desdeñada que fue sustituida por otro tipo de soberano. Este artículo explora el lugar del monarca en tres momentos claramente diferencia- dos de la conmoción revolucionaria, buscando comprender el itinerario del distancia- miento, los dilemas que hubo en juego y las implicaciones de aquella gran innovación. Palabras clave: rey, revolución, Nueva Granada. The king before the revolution: New Granada 1808-1819 Abstract The king was a central actor in the modern revolutions. He also was in the New Gre- nada Revolution of the 1810’s, during which the king went from being the center of the order as holder and guarantor of power and authority, to be a despised figure that was replaced by another kind of sovereign. This article explores the place of the monarch in three distinct moments of revolutionary upheaval, seeking to understand the way of detachment, the dilemmas that was in play and the implications of this great innovation. Key words: king, revolution, New Grenada. * Artículo recibido el 29 de enero de 2016 y aprobado el 18 de febrero de 2016. Artículo de investigación. ** Doctor en Historia. Profesor y coordinador del doctorado en Historia de la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. -

The Gregor Macgregor Scam

October 2016 | Lessons from the past 1822/3 The Gregor MacGregor scam History is full of bubbles, booms and busts, corporate William Paterson’s Darien Venture of the 1690s. collapses and crises, which illuminate the present MacGregor’s venture aimed to colonise an area of the financial world. Mosquito Coast called Poyais. Styling himself Cazique of Poyais, he and his wife, Princess Josefa of Poyais, a cousin of At Stewart Investors we believe that an appreciation Bolivar, made an exotic pair in 1820s London and were of financial history can make us more effective regarded as celebrities. investors today. Poyais, according to MacGregor, offered a marvellous investment opportunity. He claimed the area would benefit from burgeoning trade following the end of war with Spain, A case of financial and might develop further if a canal could be built across the isthmus. The Darien Scheme had been promoted with amnesia? exactly the same project in mind. Cash was raised from a number of sources. The Territory of Poyais issued 30-year bonds at an interest rate of 3%, taking advantage of the bull market in Latin American bonds to raise £200,000. In On 22 January 1823 the Kennersley Castle sailed from the addition, plots of land were sold to settlers, 100 acres Port of Leith in Scotland with 200 settlers bound for Central costing about £11. MacGregor targeted his fellow Scots as America. Two months later, when they reached their colonists, who included doctors, lawyers, farmers, artisans, destination, the colonists were shocked to find virgin jungle as well as a banker and a young man employed to manage rather than the mature settlement described by the the National Theatre of the colony. -

Islamic Organisations of Guyana

History and Politicking of Islamic Organisations in Guyana Introduction Muslims make up about fifteen percent of Guyana’s total population (see figure # 2), and they are represented by a plethora of Islamic institutions, both organisations and mosques. Jamiat-ul Ulama-E-Deen was the first Islamic Organisation established in Guyana. It was founded in 1934 by Maulvi Mohammad Ahmad Nasir. The Islamic Association of British Guiana was formed in 1936 to mobilize and preserve the Muslim identity in an ocean of evangelism. In 1936 the IABG published the first Islamic journal in Guyana, which was called Nur-E-Islam. Jamiat and IABG were defunct by the late 1930’s and the Sadr-E-Anjuman filled the void. Present day Guyana is home to a large number of Islamic organisations: Guyana United Sadr Islamic Anjuman (GUSIA), Anjuman Hifazat-ul-Islam (HIFAZ), Central Islamic Organization of Guyana (CIOG), Guyana Islamic Trust (GIT), Muslim Youth League (MYL), Muslim Youth Organization (MYO), Hujjatul Ulama/Tabligh Jamaat, Guyana Muslim Mission, the Guyana Islamic Forum (GIF), Diamond Dar Uloom, Imam Baqir Islamic Centre, and the Guyana Islamic Institute. Tensions exits between the CIOG, HIFAZ, GUSIA, MYL, GIF and the GIT. The oldest surviving organizations are the GUSIA and HIFAZ. HIFAZ, GUSIA and MYL have had a strong relationship and have been cooperating on numerous programmes. GIT sees the practice of Islam by the traditionalists who are those that attached great importance to certain practices those there Muslim ancestors who came from South Asia practiced, as corrupted with innovations (bidah). The CIOG it is trying to accommodate South Asian Muslims of the Hanafi Mazhab who attached great importance’s to some of these “traditional practices.” GIT on the other hand, brand these practices as unorthodox or bidah (innovations) that have no place in Islam. -

The Eagle 1934 (Michaelmas)

THE EAGLE u1 /kIagazine SUPPOR TED BY MEMBERS OF Sf John's College r�-� o�\ '). " ., .' i.. (. .-.'i''" . /\ \ ") ! I r , \ ) �< \ Y . �. /I' h VOLUME XLVIII, No. 214 PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY MCMXXXV CONTENTS PAGE Three Sculptured Monuments in St John's 153 Facit Indignatio Versus 156 Ceasing in Time to Sing 157 Music in New Guinea 158 "What bugle from the pine wood " 170 Frustration 172 College Chronicle: Lady Margaret Boat Club 172 Cricket 174 Hockey 176 Swimming 176 Athletics 177 Lawn Tennis 177 Rugby Fives . 178 The Natural Science Club 178 Chess . 179 The Law Society . 179 The Medical Society 180 The Nashe Society 181 The Musical Society r82 The Theological Society r83 The Adams Society 183 College Notes . 184 Obituary . 189 The Library: Additions 201 Illustrations : The Countess of Shrewsbury frontispiece Monument of Hugh Ashton fa cing p. 154 Monument of Robert Worsley " 155 Iatmul man playing flute 158 PI. I .THE EAGLE ������������������������������� VOL. XLVIII December I 934 No. 2I4 ������������������������������� THREE SCULPTURED MONUMENTS IN ST JOHN'S [The following notes, by Mrs Arundell Esdaile, are reprinted by per mission ofNE the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.] of the most notable tombs in Cambridge is that of OHugh Ashton (PI. H) who built the third chantry in the Chapel and desired to be buried before the altar. This canopied monument, with its full-length effigy laid on a slab above a cadaver, is an admirable example of Gothic just touched by Renaissance feeling and detail. The scheme, the living laid above the dead, is found in the tomb of William of Wykeham and other fifteenth-century works; but it persisted almost until the Civil War, though the slab, in some of the finest seventeenth-century examples, is borne up by mourners or allegorical figures, as at Hatfield. -

A Key Ingredient for Successful Peacekeeping Operations Management by Joseph L

No. 04-6W Landpower Essay October 2004 An Institute of Land Warfare Publication Special Operators: A Key Ingredient for Successful Peacekeeping Operations Management by Joseph L. Homza Low-intensity operations cannot be won or contained by military power alone. They require the application of all elements of national power across the entire range of conditions which are the source of the conflict.1 U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, Special Forces Peacekeeping is not a job for soldiers, but only a soldier can do it.2 Former United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammerskold Multinational and regional alliances, as well as the Charter of the United Nations, include “terms that reflect a determination to provide an international institution that could control conflict” in the Low-Intensity Conflict (LIC) spectrum of war.3 As a defense contractor employed by Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation, I recently had a unique opportunity to participate directly in the Military Observer Mission Ecuador and Peru (MOMEP), an LIC reduction operation conducted by conventional military forces with management influence by Special Operations Forces (SOF). The tenets of campaign analysis—e.g., military historical perspectives, force structure, command and control capabilities and military objectives—provide a paradigm to demonstrate clearly the effectiveness of this conflict management mission performed by SOF in accordance with the ten focus areas stipulated by John M. Collins in Special Operations Forces: An Assessment.4 The MOMEP Confidence Building Measure (CBM) was an example of SOF and conventional military force elements at their operational best. The Organization of American States (OAS), due to the actions of the SOF and conventional units assigned to MOMEP, would experience a successful CBM Peacekeeping Operation (PKO) in a regional context.