MAPA Landmine & Livelihood Survey-REPORT 1396/2017 English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Left in the Dark

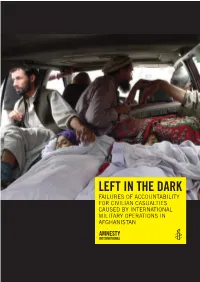

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Humanitarian Assistance Programme Biweekly Report

IOM - Humanitarian Assistance Programme Biweekly Report Week Starting Date Week Ending Date Period: 29 April 2020 12 May 2020 Submission Date: 14 May 2020 Cumulative Highlights (Verified Data on the basis of Assessments) 01 January to 12 May 2020 # of Provinces # of Reported # of Joint # of Houses # of Houses # of Houses # of People # of People # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individuals Affected ND incidents Assessments Completely Severely Moderately Deceased Injured Affected Fami- Affected Individu- Assisted by IOM Assisted by IOM Destroyed Damaged Damaged lies als 31 144 357 885 3,657 974 41 51 5,459 38,983 3,112 21,784 2019 vs 2020 Analysis Natural Disaster Weekly Highlights 29 April to 12 May 2020 # of Provinces # of ND incidents # of Joint Assess- # of Reported # of Reported # of Individuals # of Individuals # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individuals Affected Reported ments Affected Families Affected Individ- Deaths Injured Affected Families Affected Individ- Assisted by IOM Assisted by IOM uals uals 10 19 36 2,533 17,731 04 03 872 5,763 730 5,110 Natural disaster Assessment and Response Update: Nangarhar: As per the initial report obtained from ANDMA; 250 families were affected by heavy rainfall/flood in 14 districts. Four team consisting of IOM, WFP, ANDMA, ARCS conducted assessment in Achin and Shinwar districts that identified 64 families eligible for humanitarian assistance. IOM and IMC distributed NFIs while response by ARCs is still pending. Kunar: ANDMA and District authorities reported a flash flood incident in Nurgal, Khas Kunar and Chawkay districts on 04 May. Four teams consisting of IOM, WFP, DACAAR, RRD, ARCs, IMC and DG initiated assessment on 05 May. -

Regional Overview: Central Asia and the Caucasus30 January-5 February 2021

Regional Overview: Central Asia and the Caucasus30 January-5 February 2021 acleddata.com/2021/02/11/regional-overview-central-asia-and-the-caucasus30-january-5-february-2021/ February 11, 2021 Last week, violence in Afghanistan continued between the Taliban and government forces. The Taliban was also targeted by the Islamic State (IS), while Afghan forces clashed with another militia led by an anti-Taliban insurgent. In the de facto Republic of Artsakh, remnant landmines inflicted casualties on civilians and military forces for another week. Protests took place in Armenia against recent changes in the judicial system. In Georgia, demonstrations took place calling for the opening of the Armenian border, which has been closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, restricting economic migration. In Kazakhstan, oil and gas workers continue to protest for better working conditions. In Kyrgyzstan, a new round of opposition protests followed the appointment of the new parliament. In Afghanistan,1ACLED is currently conducting a review of sourcing and reporting of the conflict in Afghanistan since 2020. Afghan forces operations and airstrikes inflicted many fatalities on the Taliban last week in a number of provinces, mainly in Kandahar. Meanwhile, the Taliban attacked a military base in Khan Abad district of Kunduz, killing members of the National Security and Defense and National Civil Order Forces. The group also conducted a suicide attack using a car bomb, inflicting tens of casualties at the Public Order Police base in Nangarhar province. Such attacks have been rare since December 2020. In a separate 1/3 development, IS claimed responsibility for a roadside bomb that killed four Taliban militants in the Chawkay district of Kunar province and another that killed one policeman in Jalalabad city of Nangarhar province. -

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 20 MARCH 2010 MAJOR COUNTRY WIDE EVENTS Insurgents intend to conduct numerous attacks in the Jalalabad Region over the next 5 days SECURITY THREATS RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS UNCLASSIFIED THREAT WARNINGS NATIONWIDE: • Information at hand indicates that insurgents intend to conduct numerous attacks in the Jalalabad Region over the next 5 days. It is believed that these attacks may include suicide IEDs, rocket attacks and ambushes on Jalalabad City, Jalalabad Airfield and Government Offices. These attacks are intended to occur in the same time frame as the New Year celebrations on Sunday 22nd March. It is reported that the Insurgents and Islamic parties are warning people of Jalalabad not to participate in the New Year celebrations. • Insurgent capability and intent to carry out attacks in Kabul City remain elevated. Threat reporting continues to be received with regard to insurgent planning to conduct attacks in the city. BOLO: White corolla, reportedly 5 pax, vehicle registration #45344. • Kabul: Imminent threat of SVBIED on the road from Green Village to KIA (route BOTTLE). Privileged and Confidential 1 This information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity to which it is addressed and may contain information that is privileged, confidential and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. You are hereby notified that any dissemination, distribution, or copying of this information is strictly prohibited without the explicit approval from StrategicSSI Management. Strategic SSI - Afghanistan BREAKDOWN OF INCIDENTS REPORTED FOR AFGHANISTAN IN SSSI DSR FOR PERIOD 19 MAR – 20 MAR 2010 Incidents for report period Murder, 0 Crime, 2 Arson, 1 IDF Attack, 2 Insurgency, 4 Ambush, 3 Kidnap, 3 Attack, 6 Miscellaneous, Expl device, 4 1 Successes, 12 Table illustrating the number of Killed and Wounded, Captured and Arrested as per the reporting’s of the SSSI DSR. -

Humanitarian Assistance Programme (HAP) Weekly Summary Report

Humanitarian Assistance Programme (HAP) Weekly Summary Report “On New Responses to Natural Disasters and Follow-up” Reporting Period: 7 February 2013 – 13 February 2013 Donor: OFDA/USAID Submission Date: 13 February 2013 Incidents Update: During the reporting period three natural disaster incidents were reported. Central Region: • Parwan Province: On the 3rd of February, ANDMA reported 44 families affected by heavy rainfall in four districts of Parwan province: Sayd Khel, Bagram, Chaharikar, Surkh Parsa. One person was injured and three persons caught in an avalanche did not survive the incident in Shekh Ali district, Dara Botyan village. Consequently, the joint assessment conducted by IOM, ANDMA, CARE, ARCS, and DoRR on the 6th of February identified 27 families for immediate assistance (nine houses destroyed, 18 houses severely damaged). IOM provided winter warm clothing and blankets to these 27 families, while CARE provided nine tents and ANDMA assisted with food items. A separate assessment carried out by ANDMA recommended additional 22 families for assistance. UNICEF committed to assist 22 families with NFIs and hygiene kits. • Logar Province: On the 5th of February, ANDMA and IRC reported heavy snowfall and harsh winter affecting around 15 families in Kharwar district. Six casualties, including those of two children were also reported. Families in other districts of the province were also severely affected. In response, IOM and IRC conducted an assessment in six districts: Baraki Barak, Kharwar, Khoshi, Pul-e-Alam, Mohammad Agha and center, on the 10th of February. 152 families were confirmed for an assistance (houses severely damaged). IOM will provide winter warm clothing to all families, while IRC will provide tarpaulins, in addition to 27 latrine kits and kitchen sets to female headed families. -

Afghanistan • Flooding Situation Report #3 5 May 2009

Afghanistan • Flooding Situation Report #3 5 May 2009 HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES Serious flooding is ongoing in North, Northeast, and Western Afghanistan. 10 out of 34 provinces are affected ANDMA has called for mobilization of resources in response to the floods and in anticipation of more to come Gaps are identified in temporary shelter (all affected regions) and machinery for clearing blocked roads (North and Northeast) Stocks are depleted; authorities and aid coordination are calling for replenishment of assistance items in expectation of more flooding in the near future Heavy rains are continuing in affected areas OVERVIEW Heavy and continuing spring rains are causing widespread damage in North, Northeast and Western Afghanistan. Flood response is being coordinated by Provincial Disaster Management Committees (PDMCs), with the assistance OCHA, NGOs and UN agencies. Assistance is being distributed by local authorities, the Afghan Natural Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA), the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MoRRD), and/or the Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS). There are serious concerns about continued flooding, particularly in the north. In the west, response in some areas has been delayed because of insecurity. The following priority needs have been identified: • Provision of temporary shelter materials for immediate response and for prepositioning • Replacement of depleted stocks of emergency relief supplies in anticipation of more floods • Heavy machinery to clear blocked access roads (particularly in -

16 April 2019 Submission Date: 18 April 2019

IOM - Humanitarian Assistance Programme Weekly Report Week Starting Date Week Ending Date Period: 10 April 2019 16 April 2019 Submission Date: 18 April 2019 Cumulative Highlights (Verified Data on the basis of Assessments) 01 January to 16 April 2019 # of Provinces # of Report- # of Joint # of verified # of verified # of Houses # of Houses # of Houses # of People # of # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individ- Affected ed ND inci- Assessments Drought IDP Drought IDP Completely Severely Moderately Deceased People Affected Families Affected Assisted by uals Assisted dents (slow-onset) Individuals Destroyed Damaged Damaged Injured (slow+rapid- Individuals IOM by IOM onset) 30 82 401 1,809 12,663 10,020 15,813 211 98 66 31,936 223,552 8,883 62,181 2018 vs 2019 Analysis Natural Disaster Weekly Highlights 10 April to 16 April 2019 # of Provinces # of ND incidents # of Joint Assess- # of Reported # of Reported # of Individuals # of Individuals # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individuals Affected Reported ments Affected Families Affected Individ- Deaths Injured Affected Families Affected Individ- Assisted by IOM Assisted by IOM uals uals 14 18 25 1,514 10,598 3 6 1,440 10,080 419 2,933 Natural disaster Assessment and Response Update: Helmand: (Update of the flood Incident on 10 March) Total number of families verified: 2,475 Total number of families assisted: 0 Ongoing and Planned distribution: 2,475= The distribution is planned tentatively on 22 April 2019 as access to the district for distribution is being coordinated. Dishu district: As per the initial report from ANDMA, 400 families were reportedly affected due to flood in Dishu district on 10 March. -

Species Composition and Seasonal Variation of Anopheles Mosquitoes in Bihsud District, Nangarhar Afghanistan

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development Online ISSN: 2349-4182, Print ISSN: 2349-5979; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.72 Received: 22-09-2019; Accepted: 25-10-2019 www.allsubjectjournal.com Volume 6; Issue 11; November 2019; Page No. 162-165 Species composition and seasonal variation of Anopheles mosquitoes in Bihsud district, Nangarhar Afghanistan Ziarat Gul Mansoor1, Allah Nazar Atif2, Ajmal rasooly3 1-3 Lecturer of Biology Department, Science faculty, Nangarhar University, Daronta Jalalabad, Afghanistan Abstract Survey for the collection of Mosquitoes at district Bihsud was carried out from August 2017 to July 2018 in three targeted villages i.e. Malikbella, Belandghar and Daman, a total of 10175 Mosquitoes were collected from thirty sleeping rooms to determine Anopheles species. Anopheles Mosquitoes collection comprised by the species were A. hyrcanus (15.67%) as the most abundant mosquito species followed by A. pulcherimus (15.28%), A. fluviatilis (14.80%), A. stephensi (14.68%), A. superpictus (14.63%,),A. culicifacies (13.53%), and A. subpictus (11.38%), of the total collection. Seasonal variation of the Anopheles mosquito’s population presented a spring dominant bimodal pattern. The highest density was observed during the month of October 2017. During winter months the population density was very low. A total of 3294 Anopheles species were collected at village Daman. A hyrcanus was (511, 15.51%) found to be the most abundant species then other species of Anopheles genus. While A. culicifacies was (429, 13.02%) comparatively least abundant species. A total of 3388 Anopheles species were collected in a survey at village Malik Bella. -

The Taliban Beyond the Pashtuns Antonio Giustozzi

The Afghanistan Papers | No. 5, July 2010 The Taliban Beyond the Pashtuns Antonio Giustozzi Addressing International Governance Challenges The Centre for International Governance Innovation The Afghanistan Papers ABSTRACT About The Afghanistan Papers Although the Taliban remain a largely Pashtun movement in terms of their composition, they have started making significant inroads among other ethnic groups. In many The Afghanistan Papers, produced by The Centre cases, the Taliban have co-opted, in addition to bandits, for International Governance Innovation disgruntled militia commanders previously linked to other (CIGI), are a signature product of CIGI’s major organizations, and the relationship between them is far research program on Afghanistan. CIGI is from solid. There is also, however, emerging evidence of an independent, nonpartisan think tank that grassroots recruitment of small groups of ideologically addresses international governance challenges. committed Uzbek, Turkmen and Tajik Taliban. While Led by a group of experienced practitioners and even in northern Afghanistan the bulk of the insurgency distinguished academics, CIGI supports research, is still Pashtun, the emerging trend should not be forms networks, advances policy debate, builds underestimated. capacity and generates ideas for multilateral governance improvements. Conducting an active agenda of research, events and publications, CIGI’s interdisciplinary work includes collaboration with policy, business and academic communities around the world. The Afghanistan Papers are essays authored by prominent academics, policy makers, practitioners and informed observers that seek to challenge existing ideas, contribute to ongoing debates and influence international policy on issues related to Afghanistan’s transition. A forward-looking series, the papers combine analysis of current problems and challenges with explorations of future issues and threats. -

Regional FSAC Meeting

TYPE OF MEETING: Regional FSAC Meeting DATE & LOCATION 29 August 2016/WFP-Jalalabad Office CHAIR PERSON: Ajmal MOMMAND/OIC of WFP Jalalabad NOTE TAKER: Shapoor AMINI, Program Associate WFP Jalalabad DAIL Nangarhar, WFP, FAO, UNHCR, MADERA, FAO/FSAC, NPO/RRAA, ATTENDEES: NCRO, SOFAR, APA, UN-OCHA, WHH/GAA, DRC, NHLP, CARD-F MEETING AGENDA Item Subject Agency Presenting 1. Introduction/actions items & adoption of previous meeting All Partners minutes 2. Updates on IPC National Workshop held from 23-28 July 2016 WFP 3. Updates on IDPs UN-OCHA 4. Update on SFSA FSAC Head 5. Update on Documented Returnees UNHCR 6. FSAC partners update All Partners 7. AOB All Partners MEETING Action points RESPONSIBLE MIN ACTION ITEM TIMELINE PARTY Up-coming HEAT will be further discussed during the up-coming Proposal Proposal 1 Writing Training, in case the planned HEAT trainings is late in the FAO Writing region. Training Up to the up- Any Partner ready to re-conduct SFSA survey in Laghman. Fund 2 Any party coming FSAC are available with FSAC the candidate need to submit a proposal. Meeting Share information with FSAC regarding the documented/un- By up-coming 3 documented returnees who brings their livestock from Pakistan, UNHCR/IOM meeting while returning to country 1 | FSAC CR Minutes of Meetings‐ 20April, 2015 NEXT MEETING DATE LOCATION Because of current influx of returnees to the country it is decided to have FAO monthly meeting; the coming meeting will be on Tentatively 20th Sept 2016 MEETING MINUTES MINUTE NO: AGENDA: FACILITATOR: Introduction/actions items & adoption of 1 All Partners previous meeting minutes DISCUSSION POINTS: Mr. -

The Impact of Sada on Civil Society Knowledge, Attitudes, and Voting Behavior in Ghazni and Takhar Provinces of Afghanistan

The Impact of Sada on Civil Society Knowledge, Attitudes, and Voting Behavior in Ghazni and Takhar Provinces of Afghanistan An Evaluation Report by Corinne Shefner-Rogers, Ph.D. University of New Mexico and Arvind Singhal, Ph.D. Ohio University January 3, 2005 Submitted to Voice for Humanity Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 5 1. The VFH Sada Project ............................................................................ 7 2. Study Overview ...................................................................................... 8 . Evaluation Research Goal ............................................................ 8 . Evaluation Research Objectives ................................................... 9 3. Methodology ........................................................................................... 9 . Study Design Overview ................................................................ 9 . Study Areas .................................................................................. 10 . Study Sample ............................................................................... 12 . Sampling Procedures ................................................................... 12 . Survey Instrument ........................................................................ 13 . Data Collection ............................................................................ -

Afghanistan: Flash Flood Situation Report

Afghanistan: Flash Flood Situation Report Date: 27 April 2014 (covering 24-26 April) Situation Overview: Heavy rainfall beginning on 24 April caused flash floods in nine northern and western provinces. Initial reports obtained from provincial authorities indicate that 95 people have lost their lives and many others are still missing. In addition, the flooding has displaced more than 2,284 families and negatively impacted more than 5,565 families. The flooding also resulted in the destruction of public facilities, roads, and thousands of hectares of agricultural land and gardens. IOM, in close coordination with the Afghan National Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA) and Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC) members, mobilized to the affected areas for rapid joint assessments in order to verify the emergency needs of the affected families. Based on the findings of these assessments, IOM and partners are planning interventions for the affected populations. Highlights: • In addition to available stocks prepositioned in the Northern Region, IOM dispatched 787 Family Revitalization Kits, 400 Winter Modules, 150 Family Modules, 550 Blanket Modules, 1,000 Emergency Shelter Kits from its warehouses in Kabul and Paktia on 27 April. • According to ANDMA officials and community elders, the gabion walls recently constructed by IOM in Sar- e-Pul, Sholgara District of Balkh Province and Farkhar District of Takhar Province protected the respective communities from flooding. • IOM field staff, including female staff members, from other regions have been deployed to facilitate Joint assessments and distributions in affected parts of the Northern Region. • IOM is coordinating and actively participating in all assessments in the affected provinces.