Suspected Scaphoid Fractures in the Emergency Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gross Anatomy

www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY www.BookOfLinks.com Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the infor- mation contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the product information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY David A. Morton, PhD Associate Professor Anatomy Director Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy University of Utah School of Medicine Salt Lake City, Utah K. Bo Foreman, PhD, PT Assistant Professor Anatomy Director University of Utah College of Health Salt Lake City, Utah Kurt H. -

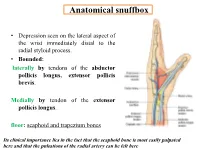

Anatomical Snuffbox

Anatomical snuffbox • Depression seen on the lateral aspect of the wrist immediately distal to the radial styloid process. • Bounded: laterally by tendons of the abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis. Medially by tendon of the extensor pollicis longus. floor: scaphoid and trapezium bones Its clinical importance lies in the fact that the scaphoid bone is most easily palpated here and that the pulsations of the radial artery can be felt here Anatomical snuffbox Anatomical snuffbox • Contents: 2) Origin of the 1) The radial artery cephalic vein pass subcutaneously over the snuffbox. 3) Superficial branch of the radial nerve pass subcutaneously over the snuffbox. Blood supply of the hand Anastomoses occur between the radial and ulnar arteries via the superficial and deep palmar arches The Deep palmar arch is formed mainly by the radial artery while the superficial palmar arch is formed mainly by the ulnar artery 3-On entering the palm, it curves laterally behind (deep) the palmar 4-The arch is aponeurosis and in front completed on (superficial) of the long flexor the lateral side tendons forming by the the superficial palmar arch superficial branch of the radial artery. 2-Then it gives off its deep branch of which runs in front of the FR , and joins the radial artery to complete the deep palmar arch 1-Enters the hand anterior (superficial) to the Superficial flexor retinaculum palmar branch of radial artery through Guyon’s canal Radial artery 5-The superficial palmar arch gives off digital arteries from its convexity which pass to the fingers and supply them Superficial palmar arch Deep palmar branch of ulnar artery Superficial palmar branch of radial artery Ulnar artery Radial artery Radial Artery first dorsal interosseous muscle 1-From the floor of the anatomical snuff-box the radial artery leaves the dorsum of the hand by turning forward between the two heads of the first dorsal interosseous muscle. -

Distal Radial Approach Through the Anatomical Snuff Box for Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Korean Circ J. 2018 Dec;48(12):1131-1134 https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2018.0293 pISSN 1738-5520·eISSN 1738-5555 Editorial Distal Radial Approach through the Anatomical Snuff Box for Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Jae-Hyung Roh, MD, PhD, and Jae-Hwan Lee , MD, PhD Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University School of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea ► See the article “Feasibility of Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention via Left Snuffbox Approach” in volume 48 on page 1120. Received: Aug 27, 2018 The anatomical snuffbox, also known as the radial fossa, is a triangular-shaped depression Accepted: Sep 17, 2018 on the radial, dorsal aspect of the hand at the level of the carpal bones. It is clearly observed Figure 1 1)2) Correspondence to when the thumb is extended ( ). The bottom of the snuffbox is supported by carpal Jae-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD bones composed of the scaphoid and trapezium. The medial and lateral borders are bounded Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal by tendons of the extensor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis, respectively. The Medicine, Chungnam National University proximal border is formed by the styloid process of the radius. Within this narrow triangular Hospital, Chungnam National University space, various structures are located, including the distal radial artery (RA), a branch of the School of Medicine, 282, Munhwa-ro, Jung-gu, radial nerve, and the cephalic vein. Daejeon 35015, Korea. E-mail: [email protected] The anatomy of the hand arteries is illustrated in Figure 2. -

Ultrasound-Guided Access of the Distal Radial Artery at the Anatomical Snuffbox for Catheter-Based Vascular Interventions: a Technical Guide

Title: Ultrasound-guided access of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: A technical guide. Authors: Anastasia Hadjivassiliou, MBBS, BSc; Ferdinand Kiemeneij, M.D, PhD; Sandeep Nathan, M.D, MSc; Darren Klass, M.D, PhD DOI: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00555 Citation: Hadjivassiliou A, Kiemeneij F, Nathan S, Klass D. Ultrasound-guided access of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: A technical guide. EuroIntervention 2019; Jaa-625 2019, doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00555 Manuscript submission date: 10 June 2019 Revisions received: 24 July 2019 Accepted date: 01 August 2019 Online publication date: 06 August 2019 Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of a "Just accepted article". This PDF has been published online early without copy editing/typesetting as a service to the Journal's readership (having early access to this data). Copy editing/typesetting will commence shortly. Unforeseen errors may arise during the proofing process and as such Europa Digital & Publishing exercise their legal rights concerning these potential circumstances. Ultrasound-guided access of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: A technical guide Anastasia Hadjivassiliou, MBBS, BSc1; Ferdinand Kiemeneij, MD, PhD2; Sandeep Nathan, MD, MSc3; Darren Klass, MD, PhD1 1. Department of Interventional Radiology, Vancouver General Hospital, University of British Columbia, Canada 2. Department of Cardiology, Tergooi Hospital, Blaricum, the Netherlands 3. University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA Short title: Ultrasound guided distal radial artery access at the anatomical snuffbox Corresponding author: Dr Darren Klass Department of Radiology, Vancouver General Hospital 899 West 12th Avenue, V5Z 1M9, Vancouver, BC, Canada Email address: [email protected] Disclaimer : As a public service to our readership, this article -- peer reviewed by the Editors of EuroIntervention - has been published immediately upon acceptance as it was received. -

Carpal Box and Open Cup Radiography

.............................................................................................................. ON THE JOB Carpal Box and Open Cup Radiography Dan L. Hobbs, M.S.R.S., Scaphoid fractures of the wrist are will include a discussion of the blood R.T.(R)(CT)(MR), is an asso- common and account for 71% of all car- supply to this bone. Next, there will be ciate professor in the depart- pal bone fractures. In the United States, a brief discussion of the mechanism of ment of radiographic science approximately 345 000 new scaphoid frac- injury, and the article will conclude with at Idaho State University in tures occur each year.1 Additionally, sta- a review of 3 positioning techniques that Pocatello. tistics have shown that scaphoid fractures can be employed to help diagnose scaph- account for 2% to 7% of all orthopedic oid fractures. Acknowledgement: Joshua fractures; they are the most commonly Howard , a student in the undiagnosed fracture.2 If an undiag- Anatomy radiographic science program nosed fracture is left without proper The scaphoid is located on the radial at Idaho State University, con- immobilization, a portion of the scaphoid side of the wrist in the anatomical snuff tributed valuable research to may die; therefore, it is imperative that box, which is located between the extensor this article. proper diagnosis, radiographic evalua- pollicis brevis and extensor pollicis longus tion and therapeutic treatment begin as tendons. (See Fig. 1.) It is the largest bone soon as possible. in the proximal row of carpals and can be The purpose of this article is to described as being complex because of its acquaint the radiographer with a few non- twisted shape; some describe it as being traditional methods used to image this boat-shaped.3 It articulates with the radius, fracture. -

Abdominal Wall Anterior 98-108 Posterior 109-11 Abductor Digiti

Index Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-72809-6 - Atlas of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Anatomy: Second Edition Dr Mike Bradley and Dr Paul O’Donnell Index More information Index abdominal wall brachialis 42 echogenicity xi anterior 98–108 – – brachioradialis 49 elbow 49 64 posterior 109 11 anterior 53–8 calcaneo-fibular – abductor digiti minimi 70, 87 ligament 193 lateral 49 52 abductor pollicis brevis 87 medial 60 calf 178–86 posterior 62–4 abductor pollicis longus 79 antero-lateral compartment – extensor carpi radialis brevis acromioclavicular joint 26–7 179 80 lateral compartment 181–2 49, 79 adductor brevis 134 posterior compartment extensor carpi radialis longus – adductor canal 151 183 6 49, 79 adductor longus 134 capsule echogenicity xi extensor carpi ulnaris 79 – adductor magnus 134, 137 carpal tunnel 70 3 extensor digiti minimi 79 air echogenicity xi cartilage echogenicity extensor digitorum 79 costal cartilage xi – extensor digitorum longus 178 anatomical snuffbox 76 7 fibrocartilage xi anisotropy ix hyaline cartilage xi extensor hallucis longus 178, 205, 218–19 ankle 187–205 chest wall 13–21 anterior 202–5 anterior 13 extensor indicis 79 – lateral 193–6 costal cartilages 13 16 extensor pollicis brevis 79 medial 197–201 lateral 17 posterior 187–92 posterior 18–21 extensor pollicis longus 79 ribs 13–16 annular ligament 52 extensor retinaculum 202 collateral ligament anterior cruciate ligament fascia echogenicity xi lateral 167 (ACL) 153–7 fat echogenicity xi medial 165 antero-lateral pelvis 127–30 ulnar (UCL) 61 femoral neck -

Hand Surgery: a Guide for Medical Students

Hand Surgery: A Guide for Medical Students Trevor Carroll and Margaret Jain MD Table of Contents Trigger Finger 3 Carpal Tunnel Syndrome 13 Basal Joint Arthritis 23 Ganglion Cyst 36 Scaphoid Fracture 43 Cubital Tunnel Syndrome 54 Low Ulnar Nerve Injury 64 Trigger Finger (stenosing tenosynovitis) • Anatomy and Mechanism of Injury • Risk Factors • Symptoms • Physical Exam • Classification • Treatments Trigger Finger: Anatomy and MOI (Thompson and Netter, p191) • The flexor tendons run within the synovial tendinous sheath in the finger • During flexion, the tendons contract, running underneath the pulley system • Overtime, the flexor tendons and/or the A1 pulley can get inflamed during finger flexion. • Occassionally, the flexor tendons and/or the A1 pulley abnormally thicken. This decreases the normal space between these structures necessary for the tendon to smoothly glide • In more severe cases, patients can have their fingers momentarily or permanently locked in flexion usually at the PIP joint (Trigger Finger‐OrthoInfo ) Trigger Finger: Risk Factors • Age: 40‐60 • Female > Male • Repetitive tasks may be related – Computers, machinery • Gout • Rheumatoid arthritis • Diabetes (poor prognostic sign) • Carpal tunnel syndrome (often concurrently) Trigger Finger: Subjective • C/O focal distal palm pain • Pain can radiate proximally in the palm and distally in finger • C/O finger locking, clicking, sticking—often worse during sleep or in the early morning • Sometimes “snapping” during flexion • Can improve throughout the day Trigger Finger: -

Causes and Assessment of Subacute and Chronic Wrist Pain

Singapore Med J 2013; 54(10): 592-598 P ictorial E ssay doi:10.11622/smedj.2013205 CMEARTICLE Causes and assessment of subacute and chronic wrist pain Janice Chin-Yi Liao1, MBBS, MRCS, Alphonsus Khin Sze Chong1,2, MBBS, FAMS, David Meng Kiat Tan1 , MBBS, MMed ABSTRACT Wrist pain is a common presentation to the general practitioner and emergency department. Most cases are simple to treat, and pain frequently resolves with conservative treatment. However, there are certain conditions, such as scaphoid nonunion and Kienböck’s disease, where delayed diagnosis and treatment can result in long-term deformity or disability. This article covers the various causes of wrist pain, recommendations on how wrist pain should be assessed, as well as details some of the common conditions that warrant specialist referral. Keywords: chronic wrist pain, physical examination, wrist injuries, wrist pain INTRODUCTION in the scapholunate interval or ulnar fossa may indicate Wrist pain is a common clinical problem.(1) Many acute cases scapholunate ligament injuries or triangular fibrocartilage are sprains or contusions following a minor injury, or tendinitis complex (TFCC) injuries, respectively. The wrist should following an episode of overuse. These problems generally then be assessed through passive and active range of motion resolve within weeks with rest, temporary immobilisation and exercises. Special tests (e.g. Finkelstein’s and Watson’s tests) symptomatic pain relief. to differentiate specific wrist conditions are described in Wrist pain that does not resolve after six weeks to three later sections. Ideally, patients with persistent swelling and months is a frequent diagnostic challenge to primary care tenderness, or a recent or remote history of trauma, should physicians. -

Section 1 Upper Limb Anatomy 1) with Regard to the Pectoral Girdle

Section 1 Upper Limb Anatomy 1) With regard to the pectoral girdle: a) contains three joints, the sternoclavicular, the acromioclavicular and the glenohumeral b) serratus anterior, the rhomboids and subclavius attach the scapula to the axial skeleton c) pectoralis major and deltoid are the only muscular attachments between the clavicle and the upper limb d) teres major provides attachment between the axial skeleton and the girdle 2) Choose the odd muscle out as regards insertion/origin: a) supraspinatus b) subscapularis c) biceps d) teres minor e) deltoid 3) Which muscle does not insert in or next to the intertubecular groove of the upper humerus? a) pectoralis major b) pectoralis minor c) latissimus dorsi d) teres major 4) Identify the incorrect pairing for testing muscles: a) latissimus dorsi – abduct to 60° and adduct against resistance b) trapezius – shrug shoulders against resistance c) rhomboids – place hands on hips and draw elbows back and scapulae together d) serratus anterior – push with arms outstretched against a wall 5) Identify the incorrect innervation: a) subclavius – own nerve from the brachial plexus b) serratus anterior – long thoracic nerve c) clavicular head of pectoralis major – medial pectoral nerve d) latissimus dorsi – dorsal scapular nerve e) trapezius – accessory nerve 6) Which muscle does not extend from the posterior surface of the scapula to the greater tubercle of the humerus? a) teres major b) infraspinatus c) supraspinatus d) teres minor 7) With regard to action, which muscle is the odd one out? a) teres -

Do You Speak Medlish?

Do You Speak Medlish? 1 MT Tools CE credit approved by Linda C. Campbell, AHDI-F s the hot rays of the summer sun blanket North kind, a reference book written especially for medical tran- America each July, my thoughts are carried back in scriptionists. In typical Pyle-esque fashion, it also contained a time to 1998. Having returned home from one of good dose of humor. Amany allied health conventions, held in a hot city that I now cannot recall, there were numerous messages on the answer- Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Dr. Andreas ing machine. With my finger hovering over the “delete mes- Grüntzig had called us and said: “Just wanted to let sage” button, I listened to one recording after another, most you know that I’m inventing a new balloon catheter; of them of no great interest. Except that last one. “Hello,” it will be a very nice thing to use in transluminal came the voice, “This is Vera Pyle. I was just calling to say dilatation and in performing angioplasties. And, by goodbye.” the way, my name is spelled G-r-ü-n-t-z-i-g, in which And so she was. Having stoically fought the good fight, case don’t forget the umlaut over the u; or else, you Vera succumbed two days later to the ravages of pancreatic can spell it Gruentzig, but in that case, don’t use the cancer. That’s what I remember about that summer. But what umlaut. However, I will answer to either.” I remember about Vera Pyle—let me tell you a story! Vera Pyle, “A Medical Transcriptionist’s Fantasy,” Journal of AAMT, Winter 1983-84 A Pioneer Story Vera Pyle was a pioneer like no other in the medical tran- Here’s the Stedman’s Medical Dictionary definition of scription industry. -

Anatomy Module 3. Muscles. Materials for Colloquium Preparation

Section 3. Muscles 1 Trapezius muscle functions (m. trapezius): brings the scapula to the vertebral column when the scapulae are stable extends the neck, which is the motion of bending the neck straight back work as auxiliary respiratory muscles extends lumbar spine when unilateral contraction - slightly rotates face in the opposite direction 2 Functions of the latissimus dorsi muscle (m. latissimus dorsi): flexes the shoulder extends the shoulder rotates the shoulder inwards (internal rotation) adducts the arm to the body pulls up the body to the arms 3 Levator scapula functions (m. levator scapulae): takes part in breathing when the spine is fixed, levator scapulae elevates the scapula and rotates its inferior angle medially when the shoulder is fixed, levator scapula flexes to the same side the cervical spine rotates the arm inwards rotates the arm outward 4 Minor and major rhomboid muscles function: (mm. rhomboidei major et minor) take part in breathing retract the scapula, pulling it towards the vertebral column, while moving it upward bend the head to the same side as the acting muscle tilt the head in the opposite direction adducts the arm 5 Serratus posterior superior muscle function (m. serratus posterior superior): brings the ribs closer to the scapula lift the arm depresses the arm tilts the spine column to its' side elevates ribs 6 Serratus posterior inferior muscle function (m. serratus posterior inferior): elevates the ribs depresses the ribs lift the shoulder depresses the shoulder tilts the spine column to its' side 7 Latissimus dorsi muscle functions (m. latissimus dorsi): depresses lifted arm takes part in breathing (auxiliary respiratory muscle) flexes the shoulder rotates the arm outward rotates the arm inwards 8 Sources of muscle development are: sclerotome dermatome truncal myotomes gill arches mesenchyme cephalic myotomes 9 Muscle work can be: addacting overcoming ceding restraining deflecting 10 Intrinsic back muscles (autochthonous) are: minor and major rhomboid muscles (mm. -

A Variant Extensor Pollicis Brevis Crossing the Anatomical Snuff Box

계명의대학술지 제36권 1호 Keimyung Med J 42 Vol. 36, No. 1, June, 2017 A Variant Extensor Pollicis Brevis Crossing the Anatomical Snuff Box Jae Hee Park, Kiwook Yang, M.D., Hyunsu Lee, M.D., Jae Ho Lee, M.D., In Jang Choi, Ph. D. Department of Anatomy, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea Received: March 27, 2017 During an educational dissection, accessory tendon of the extensor Revised: April 21, 2017 pollicis brevis muscle was found on the left side in a Korean cadaver. Accepted: May 31, 2017 Corresponding Author: In Jang Choi, Ph.D., The abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, and extensor Department of Anatomy, Keimyung University pollicis longus muscles showed normal morphology and course: School of Medicine, however, narrow muscle belly originated between the extensor pollicis 1095 Dalgubeol-daero, Dalseo-gu, Daegu 42601, brevis and extensor pollicis longus muscles. It crossed the anatomical Korea snuff box and then inserted on the base of the distal phalanx of the Tel: +82-53-250-?? E-mail: [email protected] thumb. The author describes this previously novel case report and discusses the clinical implications of such a variant. • The authors report no conflict of interest in this work. Keywords: Anatomical snuff box, Extensor pollicis brevis, Extensor pollicis longus, Variation Introduction The extensor retinaculum of the wrist forms the roof of six compartments. The first compartment contains the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB). The second compartment contains the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB). And, the third compartment, the extensor pollicis longus (EPL); the fourth compartment, the extensor digitorum and extensor indicis; the fifth compartment, the extensor digiti minimi; and the sixth compartment, the extensor carpi ulnaris.