Evidence-Based Management of Acute Hand Injuries in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatment of Comminuted Fractures of the Base of the Thumb Metacarpal Using a Cemented Bone-K-Wire Frame

Hand Surgery and Rehabilitation 38 (2019) 44–51 Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com Original article Treatment of comminuted fractures of the base of the thumb metacarpal using a cemented bone-K-wire frame Traitement des fractures comminutives de la base du premier me´tacarpien graˆce a` un cadre os-broches-ciment W. Duan, X. Zhang, Y. Yu, Z. Zhang *, X. Shao, W. Du Department of Hand Surgery, Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei 050051, PR China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: We aimed to describe the treatment of comminuted fractures of the base of the thumb metacarpal using a Received 13 June 2018 cemented bone-K-wire frame. Between March 2010 and January 2016, 41 fractures of the base of the thumb Received in revised form 8 August 2018 were treated using a cemented bone-K-wire frame. The mean age of the patients was 34 years. The patients’ Accepted 7 September 2018 history included a fall onto the hand in 7 cases, direct trauma in 31 cases, and polytrauma with an unclear Available online 11 October 2018 mechanism of injury in 3 cases. At the final follow-up, hand grip and pinch strength were measured using a dynamometer. All measurements were compared with those of the opposite hand. The patients were assessed Keywords: functionally using the Smith and Cooney score.All K-wires were left in place until the bone healed. Bone healing Cemented K-wire frame was achieved in all thumbs in an average of 5.2 weeks. Follow-up averaged 27 months. The mean hand pinch External fixator Rolando fracture andgripstrengthwas8.7 kg Æ 2.4 kgand38.4 kg Æ 5.9 kg,respectively.Themeanmeasurementsontheopposite Thumb side were 9.2 kg Æ 2.5 kg and 40.2 kg Æ 6.6 kg, respectively. -

Gross Anatomy

www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY www.BookOfLinks.com Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the infor- mation contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the product information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY David A. Morton, PhD Associate Professor Anatomy Director Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy University of Utah School of Medicine Salt Lake City, Utah K. Bo Foreman, PhD, PT Assistant Professor Anatomy Director University of Utah College of Health Salt Lake City, Utah Kurt H. -

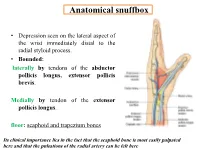

Anatomical Snuffbox

Anatomical snuffbox • Depression seen on the lateral aspect of the wrist immediately distal to the radial styloid process. • Bounded: laterally by tendons of the abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis. Medially by tendon of the extensor pollicis longus. floor: scaphoid and trapezium bones Its clinical importance lies in the fact that the scaphoid bone is most easily palpated here and that the pulsations of the radial artery can be felt here Anatomical snuffbox Anatomical snuffbox • Contents: 2) Origin of the 1) The radial artery cephalic vein pass subcutaneously over the snuffbox. 3) Superficial branch of the radial nerve pass subcutaneously over the snuffbox. Blood supply of the hand Anastomoses occur between the radial and ulnar arteries via the superficial and deep palmar arches The Deep palmar arch is formed mainly by the radial artery while the superficial palmar arch is formed mainly by the ulnar artery 3-On entering the palm, it curves laterally behind (deep) the palmar 4-The arch is aponeurosis and in front completed on (superficial) of the long flexor the lateral side tendons forming by the the superficial palmar arch superficial branch of the radial artery. 2-Then it gives off its deep branch of which runs in front of the FR , and joins the radial artery to complete the deep palmar arch 1-Enters the hand anterior (superficial) to the Superficial flexor retinaculum palmar branch of radial artery through Guyon’s canal Radial artery 5-The superficial palmar arch gives off digital arteries from its convexity which pass to the fingers and supply them Superficial palmar arch Deep palmar branch of ulnar artery Superficial palmar branch of radial artery Ulnar artery Radial artery Radial Artery first dorsal interosseous muscle 1-From the floor of the anatomical snuff-box the radial artery leaves the dorsum of the hand by turning forward between the two heads of the first dorsal interosseous muscle. -

Approach to Hand Conditions

Approach to Hand Conditions Alphonsus Chong Associate Professor, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Singapore Senior Consultant, Department of Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery, Singapore http://bit.ly/39fuCIK [email protected] Scope • Introduction – Slides at http://bit.ly/39fuCIK • And other material at: https://nus.edu/2Mh4e4s • Physical examination http://bit.ly/39fuCIK : these slides • Traumatic injuries – open and closed • Peripheral nerve problems • Masses in the hand and wrist • Tendinopathy and tendinitis • Deformity https://nus.edu/2Mh4e4s: hand wiki 3 History Taking • Pain – different aspects • Handedness • Deformity • Job v – Congenital • Hobbies – Acquired - ? Traumatic • Previous injury/ surgery • Decreased rangev of motion • Weakness • For acute trauma/conditions: • Numbness – Last meal v • Others e.g. triggering, instability – Mechanism of injury – Time/date of injury Expose both sides: subcutaneous border Scars, wasting, deformity of ulna and elbow- rheumatoid nodules Completeness and fluidity of motion Scars, wasting, deformity Quick Nerve Screen Median Nerve Radial Nerve Ulnar nerve Traumatic Injuries – Open Injuries Open traumatic injuries are a staple work of hand surgeons. Assessment of Hand – Work through the tissues (see Apley) • Skin – note size and types of wounds • Vessels - circulation • Nerves – sensation and motor • Muscle and Tendons – individual flexor and extensor tendon testing • Bones & Joints – appropriate x-rays to assess fractures/ dislocation What do you see? • LOOK • LOOK – Loss of cascade • -

Distal Radial Approach Through the Anatomical Snuff Box for Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Korean Circ J. 2018 Dec;48(12):1131-1134 https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2018.0293 pISSN 1738-5520·eISSN 1738-5555 Editorial Distal Radial Approach through the Anatomical Snuff Box for Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Jae-Hyung Roh, MD, PhD, and Jae-Hwan Lee , MD, PhD Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University School of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea ► See the article “Feasibility of Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention via Left Snuffbox Approach” in volume 48 on page 1120. Received: Aug 27, 2018 The anatomical snuffbox, also known as the radial fossa, is a triangular-shaped depression Accepted: Sep 17, 2018 on the radial, dorsal aspect of the hand at the level of the carpal bones. It is clearly observed Figure 1 1)2) Correspondence to when the thumb is extended ( ). The bottom of the snuffbox is supported by carpal Jae-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD bones composed of the scaphoid and trapezium. The medial and lateral borders are bounded Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal by tendons of the extensor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis, respectively. The Medicine, Chungnam National University proximal border is formed by the styloid process of the radius. Within this narrow triangular Hospital, Chungnam National University space, various structures are located, including the distal radial artery (RA), a branch of the School of Medicine, 282, Munhwa-ro, Jung-gu, radial nerve, and the cephalic vein. Daejeon 35015, Korea. E-mail: [email protected] The anatomy of the hand arteries is illustrated in Figure 2. -

Ultrasound-Guided Access of the Distal Radial Artery at the Anatomical Snuffbox for Catheter-Based Vascular Interventions: a Technical Guide

Title: Ultrasound-guided access of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: A technical guide. Authors: Anastasia Hadjivassiliou, MBBS, BSc; Ferdinand Kiemeneij, M.D, PhD; Sandeep Nathan, M.D, MSc; Darren Klass, M.D, PhD DOI: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00555 Citation: Hadjivassiliou A, Kiemeneij F, Nathan S, Klass D. Ultrasound-guided access of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: A technical guide. EuroIntervention 2019; Jaa-625 2019, doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00555 Manuscript submission date: 10 June 2019 Revisions received: 24 July 2019 Accepted date: 01 August 2019 Online publication date: 06 August 2019 Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of a "Just accepted article". This PDF has been published online early without copy editing/typesetting as a service to the Journal's readership (having early access to this data). Copy editing/typesetting will commence shortly. Unforeseen errors may arise during the proofing process and as such Europa Digital & Publishing exercise their legal rights concerning these potential circumstances. Ultrasound-guided access of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: A technical guide Anastasia Hadjivassiliou, MBBS, BSc1; Ferdinand Kiemeneij, MD, PhD2; Sandeep Nathan, MD, MSc3; Darren Klass, MD, PhD1 1. Department of Interventional Radiology, Vancouver General Hospital, University of British Columbia, Canada 2. Department of Cardiology, Tergooi Hospital, Blaricum, the Netherlands 3. University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA Short title: Ultrasound guided distal radial artery access at the anatomical snuffbox Corresponding author: Dr Darren Klass Department of Radiology, Vancouver General Hospital 899 West 12th Avenue, V5Z 1M9, Vancouver, BC, Canada Email address: [email protected] Disclaimer : As a public service to our readership, this article -- peer reviewed by the Editors of EuroIntervention - has been published immediately upon acceptance as it was received. -

Listen to the Associated Podcast Episodes: MSK: Fractures for the ABR Core Exam Parts 1-3, Available at Theradiologyreview.Com O

MSK: Fractures for Radiology Board Study, Matt Covington, MD Listen to the associated podcast episodes: MSK: Fractures for the ABR Core Exam Parts 1-3, available Listen to associated Podcast episodes: ABR Core Exam, Multisystemic Diseases Parts 1-3, available at at theradiologyreview.com or on your favorite podcast directory. Copyrighted. theradiologyreview.com or on your favorite podcast direcry. Fracture resulting From abnormal stress on normal bone = stress Fracture Fracture From normal stress on abnormal bone = insuFFiciency Fracture Scaphoid Fracture site with highest risk for avascular necrosis (proximal or distal)? Proximal pole scaphoid Fractures are at highest risk For AVN Comminuted Fracture at the base oF the First metacarpal = Rolando Fracture Non-comminuted Fracture at base oF the First metacarpal = Bennett Fracture The pull oF which tendon causes the dorsolateral dislocation in a Bennett fracture? The abductor pollicus longus tendon. Avulsion Fracture at the base oF the proximal phalanx with ulnar collateral ligament disruption = Gamekeeper’s thumb. Same Fracture but adductor tendon becomes caught in torn edge oF the ulnar collateral ligament? Stener’s lesion. IF Stener’s lesion is present this won’t heal on its own so you need surgery. You shouldn’t image a Gamekeeper’s thumb with stress views because you can convert it to a Stener’s lesion. Image with MRI instead. Distal radial Fracture with dorsal angulation = Colle’s Fracture (C to D= Colle’s is Dorsal) Distal radial Fracture with volar angulation = Smith’s Fracture (S -

Carpal Box and Open Cup Radiography

.............................................................................................................. ON THE JOB Carpal Box and Open Cup Radiography Dan L. Hobbs, M.S.R.S., Scaphoid fractures of the wrist are will include a discussion of the blood R.T.(R)(CT)(MR), is an asso- common and account for 71% of all car- supply to this bone. Next, there will be ciate professor in the depart- pal bone fractures. In the United States, a brief discussion of the mechanism of ment of radiographic science approximately 345 000 new scaphoid frac- injury, and the article will conclude with at Idaho State University in tures occur each year.1 Additionally, sta- a review of 3 positioning techniques that Pocatello. tistics have shown that scaphoid fractures can be employed to help diagnose scaph- account for 2% to 7% of all orthopedic oid fractures. Acknowledgement: Joshua fractures; they are the most commonly Howard , a student in the undiagnosed fracture.2 If an undiag- Anatomy radiographic science program nosed fracture is left without proper The scaphoid is located on the radial at Idaho State University, con- immobilization, a portion of the scaphoid side of the wrist in the anatomical snuff tributed valuable research to may die; therefore, it is imperative that box, which is located between the extensor this article. proper diagnosis, radiographic evalua- pollicis brevis and extensor pollicis longus tion and therapeutic treatment begin as tendons. (See Fig. 1.) It is the largest bone soon as possible. in the proximal row of carpals and can be The purpose of this article is to described as being complex because of its acquaint the radiographer with a few non- twisted shape; some describe it as being traditional methods used to image this boat-shaped.3 It articulates with the radius, fracture. -

Cause Analysis and Enlightens of Hand Injury During the COVID-19 Outbreak and Work Resumption Period

Cause analysis and enlightens of hand injury during the COVID-19 outbreak and work resumption period Qianjun Jin Zhejiang University School of Medicine First Aliated Hospital Haiying Zhou Zhejiang University School of Medicine Hui Lu ( [email protected] ) Zhejiang University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2969-4400 Research Keywords: Hand injuries, COVID-19, Outbreak, Work resumption, Medical supplies, Surgery Posted Date: December 4th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-40035/v3 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background: In light of the new circumstances caused by the current COVID-19 pandemic, an enhanced knowledge of hand injury patterns may help with prevention in factories as well as the management of related medical conditions. Methods: A sample of 95 patients were admitted to an orthopedics department with an emergent hand injury within half a year of the COVID-19 outbreak. Data were collected between January 23rd, 2020 and July 23rd, 2020. Information was collected regarding demographics, type of injury, location, side of lesions, mechanism of injuries, place where the injuries occurred, surgical management, and outcomes. Results: The number of total emergency visits due to hand injury during the COVID-19 outbreak decreased 37% when compared to the same period in the previous year. At the same time, work resumption injuries increased 40%. In comparison to the corresponding period in the previous year, most injured patients during the COVID-19 outbreak were women (60%) with a mean age of 56.7, while during the work resumption stage, most were men (82.4%) with a mean age of 44.8. -

Metacarpal Fractures

METACARPAL FRACTURES BY LORYN P. WEINSTEIN, MD, AND DOUGLAS P. HANEL, MD The majority of metacarpal fractures are closed injuries amenable to conservative treatment with external immobilization and subsequent rehabilitation. Internal fixation is favored for unstable fracture patterns and patients who require early motion. Percutaneous pinning usually is successful for metacarpal neck fractures and comminuted head fractures. Shaft and base fractures can be treated with pinning or open reduction and internal fixation; the latter, being more rigid, allows early rehabilitation. External fixation has a limited yet defined role for metacarpal fractures with complex soft-tissue injury and/or segmental bone loss. The recent development of bioabsorbable implants holds promise for skeletal rigidity with minimal soft-tissue morbidity, but long-term in vivo data support- ing the use of these implants is not currently available. Copyright © 2002 by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand arly treatment of metacarpal fractures was lim- Surgical techniques rapidly expanded to include ret- ited to the only tools available: manipulation rograde fracture pinning, intramedullary pinning, and Eand casting. The discovery of percutaneous transfixion pinning. Many of the K-wires in use today fracture fixation near the turn of the century opened have the same diamond-shaped tip and sizing speci- up a new world of possibilities. It was 25 years after fications as the original design. Bennett’s original manuscript that Lambotte de- The first plate and screw set for the hand was scribed the first surgical stabilization of a basilar introduced in the late 1930s. By today’s standards, the thumb fracture by using a thin carpenter’s nail.1 By Hermann Metacarpal Bone Set was quite lean; it 1913, Lambotte had authored a fracture text with included 3 longitudinal plates of 2, 3, and 4 holes, a multiple examples of pinning, wiring, and plating of drill, screwdriver, and 9 screws.1 Improvements in hand fractures. -

Injury-Induced Hand Dominance Transfer

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 INJURY-INDUCED HAND DOMINANCE TRANSFER Kathleen E. Yancosek University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Yancosek, Kathleen E., "INJURY-INDUCED HAND DOMINANCE TRANSFER" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 18. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kathleen E. Yancosek The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 INJURY-INDUCED HAND DOMINANCE TRANSFER _________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rehabilitation Sciences in the College of Health Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Kathleen E. Yancosek Lexington, Kentucky Director: Carl Mattacola, PhD, ATC Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Kathleen E. Yancosek 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION INJURY-INDUCED HAND DOMINANCE TRANSFER Hand dominance is the preferential use of one hand over the other for motor tasks. 90% of people are right-hand dominant, and the majority of injuries (acute and cumulative trauma) occur to the dominant limb, creating a double-impact injury whereby a person is left in a functional state of single-handedness and must rely on the less- dexterous, non-dominant hand. When loss of dominant hand function is permanent, a forced shift of dominance is termed injury-induced hand dominance transfer (I-IHDT). -

Unusual Ignition of a Bullet Causing Hand Injury: Case Report

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Injury Extra 45 (2014) 9–11 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Injury Extra jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/inext Case report Unusual ignition of a bullet causing hand injury: Case report a, b b b Abdul Kerim Yapici *, Salim Kemal Tuncer , Umit Kaldirim , Ibrahim Arziman , c Mehmet Toygar a Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, Ankara, Turkey b Department of Emergency Medicine, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, Ankara, Turkey c Department of Forensic Medicine, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, Ankara, Turkey A R T I C L E I N F O Article history: Accepted 10 November 2013 1. Introduction 2. Case report The incidence of firearm related non-fatal and fatal accidents A 35 year-old man was admitted to emergency department has increased worldwide [1–5]. Most of firearm accidents result with a complaint of injury related to the third web space, third often due to human errors included extreme carelessness while finger pulp and thenar region of right hand. On detailed handling, carrying or storing a loaded firearm [3]. Most of the questioning, he reported that he was cleaning a machine gun unintentional or intentional nonfatal gunshot injuries involve an (type MG-3) after target practice in a shooting range. He did not extremity [6]. Most gunshot injuries to the hand are result of low- check visually and physically whether there were any bullets or velocity handguns [7]. While low-energy firearm injuries are not in the chamber.