Unit 5 Early Medieval Polities in North India, 7Th to 12Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 3 the Pushyabhutis and the Rise of Harsha*

History of India from C. 300 C.E. to 1206 UNIT 3 THE PUSHYABHUTIS AND THE RISE OF HARSHA* Structure 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2 The Changing Political Scenario in North India 3.2.1 New Type of Political Centres: the Jayaskandhavaras 3.2.2 Kanauj as the New Political Centre 3.2.3 Decline of Pataliputra 3.3 The Pushyabhutis 3.4 The Political Activities of Harsha 3.4.1 Sources 3.4.2 Political Activities of Harsha: An Overview 3.4.3 The Extent of Harsha’s Kingdom 3.4.4 Xuan Zang’s Account 3.4.5 Harsha Era 3.4.6 End of Harsha’s Reign 3.5 The Changing Structure of Polity 3.5.1 Titles of Kings 3.5.2 Administration 3.5.3 Political Structure 3.6 Aftermath: The Tripartite Struggle for Kanauj 3.7 Summary 3.8 Key Words 3.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 3.10 Suggested Readings 3.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this Unit, you will be able to learn: how the political scenario of north India changed in the 5th-6th century CE; the emergence of new types of political centres – the Jayaskandhavaras; why Kanauj became the new political centre of North India; Harsha’s political activities; the extent of Harsha’s ‘empire’; the changing political structure of north India; and impact of the rise of Kanauj: the Tripartite struggle. 3.1 INTRODUCTION The political scenario in post-Gupta north India was characterised by the emergence of numerous ruling families like the Maukharis of Kanyakubja, later 34 *Dr. -

Banabhatta : Harshacharita

ANCIENT INDIAN HISTORY & ARCHAEOLOGY, PATNA UNIVERSITY, PATNA Banabhatta : Harshacharita PG / PGM.A. / 3M.A.rd Sem 3 rd Semester CC-12, Historiography, History of Bihar & Research Methodology Dr. Manoj Kumar Assistant Professor (Guest) Dept. of A.I.H. & Archaeology, Patna University, Patna-800005 Email- [email protected] P ATNA U NIVERSITY , PATNA Banabhatta : Harshacharita Banabhatta: Harshacharita Of all the extant historical biographies of ancient times, mention may first be made of the Harsacarita of Banabhatta), the court poet-cum-historian of Harsa (AD 606-48) of Sthanvisvara (modern Thaneswar in Haryana) and Kanyakubja (Kanauj). Bana himself calls his work an akhyayika as it has a historical basis. It consists of eight ucchavasas (chapters). Personal Life of Banabhatta In the first chapter, the author speaks of his own ancestry and lineage. According to the information supplied by him, he was the son of Citrabhanu in the Vatsyayana line of the Bhargava Brahmanas. His ancestral home was at Pritikuta, a village situated on the western bank of the river Sona within the limits of the kingdom of Kanyakubja. The first three chapters are devoted, of course, partly to the life and family of the author himself. He belonged to the family, which was famous for scholarly tradition. His inclination towards or interest in history was quite consistent with his family tradition. Ancestry of Harshavardhana Harsa’s ancestors find mention in the third chapter of the Harsacarita. The author of the work informs us that it was Pusyabhuti who founded the kingdom of Srikantha with its capital at Sthanvisvara (in the late fifth or early sixth century AD). -

Thegupta Dynasty– History Study Materials

TheGupta Dynasty– History Study Materials THE GUPTA DYNASTY (AD 320-550) The Gupta Dynasty Era is often remembered as the central Asia), who were yet another group in the long Classical Age. Under the Gupta rulers, most of North succession of ethnically and culturally different India was reunited. The Gupta Empire extended from outsiders drawn into India and then woven into the the Brahmaputra to the Yamuna and Chambal, from hybrid Indian fabric. the Himalayas to the Narmada. Because of the relative Coins of Kushana Dynasty peace, law and order, and extensive cultural achievements during this period, it has been described The Kushana ruler used their coinage to establish as a Golden Age that crystallised the elements of what and highlight their own superiority. The Idea of is generally known as the Hindu culture, showing the ruler on the coins was not popular in India. All the previous dynasties minted; coins The Gupta depicting only symbols. The Kushana rulers Dynasty popularised this idea which remained in use for the next 2,000 years. The coinage system developed by Shri Gupta (Founder) the Kushanas was copied by the later Indian 319-335 CE dynasties such Guptas, as well as by the neighbouring rulers such as Sassdnians (of Persia). Samudragupta 335- It is very unfortunate that very few evidences of the 376 CE Kushana rule could be found today. Perhaps, the coins are only evidence we have of this illustratious dynasty. Kushana coins tell so much about the Chandragupta Ramagupta images of the kings. The coins tell us how the rulers 376-451 CE wished to be see by their subjects. -

Avantivarman (Varman Dynasty)

Avantivarman (Varman dynasty) Avantivarman is believed to be the last king of the Varman dynasty of Kamarupa in present-day North-East India. No direct evidence of this king exists, nor does this name appear anywhere in a historical record ┠the name Avanti Varma itself is reconstructed from the benedictory verses of a Sanskrit play Mudrarakshasa by Vishakhadatta. According to some scholars, the "Avantivarma" of Mudrarakshasa is actually another king of the Maukhari dynasty. Avantivarman was a king who founded the Utpala dynasty. He ruled Kashmir from 855 to 883 CE and built the Avantiswami Temple. Avantivarman was the grandson of Utpala, one of the five brothers who had taken control of the Karkota throne. Raised by Utpala's minister Sura, Anantivarman ascended the throne of Kashmir on 855 CE, establishing the Utpala dynasty and ending the rule of the Karkotas. Avantivarman appointed Suyya, an engineer and architect as his prime minister. The country had been badly Avanti Varman was a king who founded the Utpala dynasty. He ruled Kashmir from 855 to 883 CE and built the Avantiswami Temple. Avanti Varman was the grandson of Utpala and was raised by Utpala's minister Sura. He ascended the throne of Kashmir on 855 CE, establishing the Utpala dynasty and ending the rule of Karkota dynasty. Avanti Varman appointed Suyya, an engineer and architect as his prime minister. The country's economy had been badly affected due to the numerous civil wars over the last forty Avantivarman (Varman dynasty). From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Avanti Varman is believed to be the last of the Varman dynasty who ruled Kamarupa briefly after Bhaskar Varman before being overthrown by Salasthambha, the founder of the Mlechchha dynasty.[1]. ^ "(T)he king from whom the throne was captured by Salasthamba must have been the immediate successor of Bhaskarvarman." (Sharma 1978, p. -

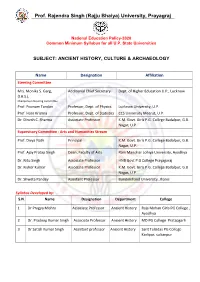

Prof. Rajendra Singh (Rajju Bhaiya) University, Prayagraj

Prof. Rajendra Singh (Rajju Bhaiya) University, Prayagraj National Education Policy-2020 Common Minimum Syllabus for all U.P. State Universities SUBJECT: ANCIENT HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY Name Designation Affiliation Steering Committee Mrs. Monika S. Garg, Additional Chief Secretary Dept. of Higher Education U.P., Lucknow (I.A.S.), Chairperson Steering Committee Prof. Poonam Tandan Professor, Dept. of Physics Lucknow University, U.P. Prof. Hare Krishna Professor, Dept. of Statistics CCS University Meerut, U.P. Dr. Dinesh C. Sharma Associate Professor K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badalpur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Supervisory Committee - Arts and Humanities Stream Prof. Divya Nath Principal K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badalpur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Prof. Ajay Pratap Singh Dean, Faculty of Arts Ram Manohar Lohiya University, Ayodhya Dr. Nitu Singh Associate Professor HNB Govt P.G College Prayagaraj Dr. Kishor Kumar Associate Professor K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badalpur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Dr. Shweta Pandey Assistant Professor Bundelkhand University, Jhansi Syllabus Developed by: S.N. Name Designation Department College 1 Dr Pragya Mishra Associate Professor Ancient History Raja Mohan Girls PG College , Ayodhya 2 Dr. Pradeep Kumar Singh Associate Professor Ancient History MD PG College Pratapgarh 3 Dr Satish Kumar Singh Assistant professor Ancient History Sant Tulsidas PG College Kadipur, sultanpur Prof. Rajendra Singh (Rajju Bhaiya) University, Prayagraj Semester-wise Titles of the Papers Year Sem. Course Course Title Theory/ Maximum Maximum -

BLOCK 2 GUPTAS and POST-GUPTA STATE and SOCIETY India : 200 BCE to 300 CE

BLOCK 2 GUPTAS AND POST-GUPTA STATE AND SOCIETY India : 200 BCE to 300 CE 92 Trade Networks and UNIT 6 THE RISE OF GUPTAS: ECONOMY, Urbanization SOCIETY AND POLITY* Structure 6.0 Objectives 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Antecedents 6.3 Political History of the Guptas 6.4 Administration 6.5 Army 6.6 Economy 6.7 Society 6.8 Culture under the Guptas 6.9 Decline of the Guptas 6.10 Summary 6.11 Key Words 6.12 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 6.13 Suggested Readings 6.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this Unit, you will learn about, political conditions in India at the beginning of the fourth century CE; expansion and consolidation of the Gupta empire; order of succession of the Gupta rulers and their military exploits; administration, economy, society and culture under the Guptas; and the decline of the Guptas. 6.1 INTRODUCTION In this Unit, you will become familiar with the political history of the Gupta period. Compared to the pre-Mauryan and Mauryan periods, the number of ruling families had increased considerably in the post-Mauryan period. This means that (i) more and more areas were experiencing the emergence of local states; these states which may have been small were represented by local ruling families, (ii) when large state structures arose these small local states either lost their separate existence or they continued as subordinates within larger areas. One such large state structure which began to emerge from the beginning of the fourth century CE was that of the Guptas. In this Unit, we will look at the political, social and economic aspects of the Gupta period. -

Later Guptas in India Study Materials

Later Guptas In India Study Materials collapsed, its fragmented remnants existed here LATER GUPTAS and there, till they too. finally disappeared from Chandragupta II had two queens, the historical map of India by the end of sixth Dhruvadevi and Kuberanaga Govindagupta and centun ad. After the decline of the Gupta Kumaragupta I were the two sons of Empire, another line of kings with names ending Chandragupta (I from the first queen and a with ‘Gupta’ rose in the Magadh region. daughter Vakataka was from his second queen. However, there is no evidence of their Kumaragupta I ascended the throne after his genealogical relationship with that of the father Chandragupta II, in AD 414 Although not Imperial Guptas. The Vallahha in Gujarat, the many details of his reign are ava,ilable, he ruled Gowda-padas in Bengal and the descendants of close to 40 years dunng which he performed the Pushyabhuti in Sthaneshwar became Ashvamedha yajna, which indicates his military independent Simultaneously, another line of Towards the end of his life the Gupta Empire Mukhari kings emerged m the northern Ganges was constant threat of invasion by the Hunas plains of Kanauj. Out of the chaos emerged the rulers. He died in AD 455. His son, powerful kingdom of Sthaneshwar. Towards the Skandagupta Vikramaditya (AD 455- end of the century, the Maukari dynasty. 467)succeeded him. But Skandagupu had to face Mukharis defeated the Guptas and captured the a political crisis, because of the threat from the entire of the Magadha region. The Guptas then other heirs to the moved towards the east, where they came throne, during his 12 years of reign. -

The Maukharis of Kanauj

AJMR Asian Journal of Multidimensional Research A Publication of TRANS Asian Research Journals Vol.2 Issue 6, June 2013, ISSN 2278-4853 THE MAUKHARIS OF KANAUJ Dr. Moirangthem Pramod* *Assistant Professor, G. G. D. S. D. College, Chandigarh, India. INTRODUCTION With the coming of kumāragupta III on the throne of Magadha, the weakness of the imperial Gupta had become a known fact to all. Taking advantage of the situation some feudatories of the Guptas raised their heads to grab the political power in north India to establish their own independent kingdoms. Among these feudatories, the Maukharies of kanauj was one of them. This branch of the Maukharis is known from the seals and inscriptions discovered from the modern districts of Farrukhabad, Gorakhpur, Jaunpur and Barabanki of Uttar Pradesh, Patna district of Bihar, Nimad district of Madhya Pradesh and from the literary work like Bāṇa‟s Harshacharita. As most of the seals and inscriptions of this Maukhari family are discovered from the above mentioned district of Uttar Pradesh, their seat of power should be roughly placed in this part of the state. Even though, we do not have any hard facts about the capital of this ruling family, it is generally agreed that Kanauj (ancient Kānyakubja) must have been the center of their rule.1 Harivarman is described as the progenitor of the Kanauj branch of Maukharis. In the inscriptions and seals which we have discovered till now, he is given the simple title, Mahārāja indicative of his feudatory position. It is very likely that he was the contemporary of Kṛishṇagupta, the founder of the Later Gupta dynasty. -

Political Structures in India.Pdf

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Political Structures In India Subject: POLITICAL STRUCTURE IN INDIA Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Early State Formation Pre-State to State, Territorial States to Empire, Polities from 2nd Century B.C. to 3rd Century A.D., Polities from 3rd Century A.D. to 6th Century A.D State in Early Medieval India Early Medieval Polities in North India, 7th to 12th Centuries A.D., Early Medieval Polities in Peninsular India 6th to 8th Centuries A.D., Early Medieval Polities In Peninsular India 8th To 12 Centuries A.D. Administrative and Institutional Structures Administrative and Institutional Structures in Peninsular India, Administrative and Institutional Systems in North India, Law and Judicial Systems, State Under the Delhi Sultanate, Vijayanagar, Bahmani and other Kingdoms, The Mughal State, 18th Century Successor States Colonization-Part I The Eighteenth Century Polities, Colonial Powers Portuguese, Dutch and French, The British Colonial State, Princely States Colonization Part II Ideologies of the Raj, Activities, Resources, Extent of Colonial Intervention Education and Society, End of the Colonial State-establishment of Democratic Polity. Suggested Reading: 1. Social Change and Political Discourse in India: Structures of Power, Movements of Resistance Volume 4: Class Formation and Political Transformation in Post-Colonial India by T. V. Sathymurthy, T. V. Sathymurthy 2. Political parties and Collusion : Atanu Dey 3. The Indian Political System : Mahendra Prasad Singh, Subhendu Ranjan Raj CHAPTER 1 Early State Formation STRUCTURE Learning objectives Pre-state to state Territorial states to empire Polities from 2nd century BC. -

A) General Features of the Society ^ Some Knowledge of the Social Life of People During the Period Being Reviewed Can Be Derived

a) General Features of the Society ^ some knowledge of the social life of people during the period being reviewed can be derived from information contained in Inscriptions# numismatic sources# and literature including the accounts left by foreign pilgrims. A very general picture that emerges is of a ccranunity of individuals - honest and hard working# among whom interactions were polite and governed by rules of social conduct# who were pious and orthodox as far as religion was concerned^# and who held learning and education in great respect. Pa Hien's writings are informative as regards the societal norms and customs of the people. Guests and learned individuals# held in high esteem, were treated well as in the case of an honoured monk who was received with due hospitality* Yuan-Chwang' writing about his own experiences on his arrival at Nalanda Mahavihara# mentions the special seat and other facilities he was offered. Various references in Kalidasa's works also support the claim that visitors were# as a rule# treated with utmost 46 hospitality. Guests were considered as gods# worthy of 4 worship • On arrival# an honoured guest was first offered water to wash his feet, then asked to grace a seat made of cane-weed^/ following which he would accept offerings of rice# honey# fruits etc. Sources provide considerable information on the various modes of greeting and salutation. It was considered custcxnary for a disciple to touch the feet of his preceptors; similarly a son was respected to touch his parents feet in return for which he received their 7 blessings • Various norms governed interactions between people - while talking to elders and respected members of the ccwimunity# people were expected to address them courteously and even bow before them. -

History of Ancient India

BIG LEARNINGS MADE EASY An initiative of Group HISTORY OF ANCIENT INDIA Civil Services Examination MADE EASY Publications Corporate Office: 44-A/4, Kalu Sarai (Near Hauz Khas Metro Station), New Delhi-110016 E-mail: [email protected] Contact: 011-45124660, 8860378007 Visit us at: www.madeeasypublications.org History of Ancient India © Copyright, by MADE EASY Publications. All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the above mentioned publisher of this book. First Edition: 2017 Second Edition: 2018 Third Edition: 2019 © All rights reserved by MADE EASY PUBLICATIONS. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form without the written permission from the publisher. Contents History of Ancient India Unit – I: Different Shades of Civilization Family Life ..........................................................43 Social Life ...........................................................43 Chapter-1 Social Divisions ..................................................44 Indian Pre-History............................................2 Religious Life of Aryans ......................................45 1.1 Introduction ..........................................................2 Deities of Early Vedic Period ..............................45 1.2 Paleolithic Age .....................................................3 -

Observations on the History and Culture of Daks.In.A Kosala

Observations on the History and Culture of Daks.in. a Kosala∗ Fifth to Seventh Centuries ad Introduction The historiography of the region called Daks.in. a Kosala, nowadays generally known as Chhattisgarh, is beset with difficulties of a predominantly chrono- logical nature. Apart from quite a number of inscriptions, we do not possess written sources that can help us to unravel its early history. The chronological problems are due to the fact that, with one isolated exception, the charters of its kings are dated in regnal years. Moot questions, such as the dating of the kings of Sarabhapur,´ the relation, if any, between the P¯an. d. ava dynasties of Mekal¯aand Kosala, or the date of King T¯ıvaradeva, have been discussed again and again by a number of scholars during the last fifty years, a debate that has been dominated by three eminent Indian epigraphists, V.V. Mirashi, D.C. Sircar, and A.M. Shastri. A first reading of this facinating corpus of learned articles gives the uncomfortable feeling that these three scholars dis- agree among themselves on almost every issue. Only laborious study makes one realize that in this debate a large body of historical evidence has been dis- closed and evaluated, as a result of which we know to date considerably more about the history and culture of this region than half a century ago. Still, many inscriptions await publication and this is, unfortunately, in particular true for those on stone. Unlike copperplate charters, stone epigraphs often inform us about particular historical circumstances and details beyond the official royal records.