Patch Use by Cattle in Dryland Zimbabwe: Farmer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty of Arts Department of History And

FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES RESOURCE NATIONALISM AND LOCAL EMPOWERMENT, THE CASE OF ZVISHAVANE COMMUNITY SHARE OWNERSIP TRUST, 2012 TO 2017. By FAITH MAFUNGA R147013M SUPERVISOR: DR T. MASHINGAIDZE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF THE MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS IN HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES HONOURS DEGREE. ZVISHAVANE, ZIMBABWE JUNE 2018 Declaration I, Faith Mafunga declare that this dissertation hereby submitted for the Bachelor of Arts Honors Degree in History and International Studies at Midlands State University is my own effort. Information from published and unpublished work from other authors have been acknowledged. …………………………. ……………………………… Student Date i Approval form The undersigned certify that they have supervised and recommended to Midlands State University the student FAITH MAFUNGA dissertation entitled RESOURCE NATIONALISM AND LOCAL EMPOWERMENT, THE CASEOF ZVISHAVANE COMMUNITY SHARE OWNERSIP TRUST, 2012 TO 2017. The dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the History and International Studies Department. …………………………. ……………………………… Supervisor Date …………………………… …………………………………. Chairperson Date …………………………. ……………………………………… External Examiner Date ii Dedication This piece of work is dedicated to my late father Mr. E.C Mafunga, my mother Mrs. E Mauto, my siblings Yvonne, Tanaka and Tafadzwa Mafunga. Thank you all for your constant love and support. God Bless you. iii Acknowledgements Utmost gratitude goes to God Almighty for he has been an unwavering source of strength throughout my academic years. I must pay tribute to my academic supervisor Doctor Mashingaidze who has given me supervision and motivation throughout this research. My exceptional gratefulness also goes to Mr. N.T Jinga the C.E.O of ZCSOT and the entire organization for helping me in crafting this dissertation. -

High Frequency Monitoring Report Bulletin #21 | February 2019

Bulletin #21 • February 2019 • www.zrbf.co.zw The purpose of the ZRBF High Frequency Monitoring Bulletin is to avail real IN THIS REPORT time data and information on identified and agreed trigger indicators for Overall Results and Implications 2 the activation of the crisis modifier, performance monitoring, programming Implications and Actions related to Resilience and other decisions for the overall ZRBF adaptive programme management. Programming 4 Information presented in this bulletin is readily available in the HFM Online Status Update on Macro-Trigger Indicators 5 Database, accessible using this url Vegetation Condition Index 5 https://197.155.231.242/undp/ZRBF/HFMS/index.php Real-time water levels in major rivers 5 The bulletin contains official information for the month of January 2019 collected Summary of Broad Classification: Micro Trigger from various sources by ZRBF partners and analysed by ZRBF PMU. The High Indicators 5 Frequency Monitoring Bulletin is a product of collaboration between the ZRBF Detailed Micro Trigger Indicators Update 6 Partners and other government agencies. For questions and comments regarding National Media Monitoring for Early-Warning this bulletin, kindly get in touch withVhusomuzi Sithole (vhusomuzi.sithole@ Signals 10 undp.org), Alfios Mayoyo ([email protected]) or Rufael Fassil (rufael. Annex 1: Flood monitoring thresholds for water [email protected]). level in selected rivers 11 UNDP Zimbabwe, ZRBF Programme Management Unit Arundel Office Park, Block 9, Norfolk Rd, Mt. Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe, Phone: +263 4 338836-44 Page 2 | High Frequency Monitoring Report Bulletin #21 | February 2019 Overall Results and Implications Summary Classification Key Highlights According to the High Frequency Monitoring (HFM) classification, 15 districts were rated “Alert” and the remaining three did not report. -

Climate-Smart Agriculture Manual for Zimbabwe, Climate Technology Centre and Network, Denmark, 2017

Climate-Smart Agriculture supporting low carbon and climate resilient development Climat e-Smart A griculture Manual f or A griculture Educ The Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN) fosters technology transfer and deployment at the request of developing countries through three core services: technical assistance, capacity building and scaling up international collaboration. The Centre is the operational arm of the UNFCCC Technology Mechanism, it is hosted and managed by Email: [email protected] the United Nations Environment and the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation Web: www.ctc-n.org (UNIDO), and supported by more than 300 network partners around the world. ation in Zimbab CTCN Supported by: w e United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Climate-Smart Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation and Irrigation Development Department of Agriculture Education and Farmer Training Agriculture Manual Ngungunyana Building No. 1 Borrowdale Road for Agriculture Education in Zimbabwe Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: +263 (0) 4 797390 Email: [email protected] www.moa.gov.zw Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate 11th Floor, Kaguvi Building, Cnr S. V. Muzenda Street and Central Avenue, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: +263-4-701681/3 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.climatechange.org.zw Climate-SmartClimate-SmartClimate-SmartClimate-Smart AAAgricultureAgriculturegriculturegriculture Manual ManualManual Manual for ffAororgriculturefor AA griculturegricultureAgriculture Educ EducEduc Educationationationation in Zimbab inin -

Food Assistance Severely Underfunded Humanitarian Bulletin

Humanitarian Bulletin Zimbabwe 01– 30 November 2013 In this issue STA spreads to 19 districts P.1 Cholera resurges in Masvingo P.2 HIGHLIGHTS Significant slump in migration P.3 A severe funding shortage has affected the Seasonal Latest on funding P.4 Targeted Assistance (STA) programme, prompting A woman picks some grain from the ground to avoid wastage after the bag tore. Photo courtesy of Matilda Moyo/OCHA. partners to distribute half rations in efforts to spread the limited resources. Food assistance severely underfunded A fresh cholera outbreak has been reported in Masvingo Resources Urgently Needed to Avert Ration Breaks and Size Reductions province after a five month In response to Zimbabwe’s deteriorating food security situation, the Seasonal Targeted reprieve. Assistance (STA) programme that started in October increased to 19 rural districts in November. Assistance is in the form of rations comprising cereal, oil and pulses, while cash Partners have observed a is being distributed in areas with functioning markets so people can buy cereals from local slump in irregular migrants sources. deported from SA and WFP and partners plan to scale up assistance until the next Botswana, as well as Third The STA is so far harvest in April 2014, reaching around 1.8 million people in Country Nationals assisted. 43 districts, subject to funding availability. Christian Care, by Australia, funded through support from the Canadian Grain Bank will also European Union (EU), Japan, UK, USA and the Central assist two districts - Chimanimani and Matobo. Emergency Response Fund Despite generous contributions from donors, the STA (CERF). FIGURES programme is severely underfunded with only half the needs catered for. -

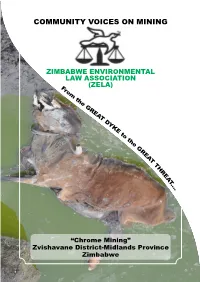

Community Voices on Mining

COMMUNITY VOICES ON MINING ZIMBABWE ENVIRONMENTAL LAW ASSOCIATION (ZELA) “Chrome Mining” Zvishavane District-Midlands Province Zimbabwe Page 1 COMMUNITY VOICES ON MINING “From The Great Dyke to The Great Threat” A narrative and picture testament of the impacts of chrome mining activities in Zvishavane. By MUKASIRI SIBANDA (Economic Governance Officer - ZELA) Page 2 Background and Introduction “I have learnt that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel” Maya Angelou Much has been said or perhaps done to move duty bearers (government and mining companies) into action on mitigating the negative impacts of mining. This narrative and picture piece seeks to appeal the emotions of duty bearers to take an urgent audit of the impacts of their actions or inactions in addressing what many locals call, in plain Shona language, “gona rama chingura” (the curse) that has brought poverty, misery and even death to some communities living near chrome mining areas in the Great Dyke. The Great Dyke has turned out to be The Great Threat. The presence of abundant mineral wealth offers exciting opportunities to charm the socioeconomic transformation of poor host mining communities and the general citizenry. This is acknowledged by the country’s 5 year economic blueprint; the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio Economic Transformation (ZIMASSET 2013- 2018) which is anchored on “judicious exploitation of mineral resources”. Yet in reality, the socio-economic charm and benefits from mineral wealth abundance has been privatised by corporates and few corrupt, politically well-connected individuals. Host mining communities find obscured the “C” in the Charm of mineral wealth abundance but only see the Harm. -

High Frequency Monitoring Report

Bulletin #41 • October 2020 • www.zrbf.co.zw IN THIS REPORT Overall Results and Implications The purpose of the ZRBF High Frequency Monitoring Bulletin is to avail Status Update Macro-Indicators real time data and information on identified and agreed trigger indicators for the activation of the crisis modifier, performance Vegetation Condition Index monitoring, programming and other decisions for the overall ZRBF Summary of Broad Classification: Micro Trigger adaptive programme management. Information presented in this Indicators bulletin is readily available in the HFM Online Database, accessible using this urlhttps://197.155.231.242/undp/ZRBF/HFMS/index.php . Detailed Micro Trigger Indicators Update and The bulletin contains official information for the month of October 2020 Proposed Mitigatory Activities collected from various sources by ZRBF partners and analysed by Biophysical Trigger indicators ZRBF PMU. The High Frequency Monitoring Bulletin is a product of Production Trigger indicators collaboration between the ZRBF Partners and other government Access Trigger Indicators agencies. For questions and comments regarding this bulletin, kindly Trade Trigger Indicators get in touch with Vhusomuzi Sithole ([email protected]), Shupikai Mutyambizi ([email protected] ). 1 UNDP Zimbabwe, ZRBF Programme Management Unit Arundel Office Park, Block 9, Norfolk Rd, Mt. Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe +263 4 338836-44 Table of Contents 1. Overall Results and Implicaons ......................................................................................................... -

Use and Management of Homegarden Plants in Zvishavane District, Zimbabwe

Tropical Ecology 54(2): 191-203, 2013 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com Use and management of homegarden plants in Zvishavane district, Zimbabwe ALFRED MAROYI * Biodiversity Department, School of Molecular and Life Sciences, University of Limpopo, Private Bag X1106, Sovenga 0727, South Africa Abstract: This study was aimed at documenting use and management of plant species growing in homegardens in Zvishavane district, Zimbabwe. The findings of this study were derived from qualitative and quantitative data collected from 31 homegardens in Zvishavane district between March and December 2009. The study documented information on management of plants growing in homegardens; their numbers, composition and uses. Household interviews and homegarden surveys revealed that 73 species were important to local livelihoods. Vegetables, fruits, ornamentals and medicines were the most important use categories. Among 73 plant species growing in homegardens, 52 species were cultivated and the rest were non-crop species. Cultivated species were actively managed but the management of non-crop species was passive (i.e. were tolerated and protected). These results revealed that homegardens satisfy various household needs such as food, ornamentals, medicines, building materials, religious and ceremonial uses. Resumen: El objetivo de este estudio fue documentar el uso y el manejo de especies vegetales que crecen en huertos familiares en el distrito Zvishavane, Zimbabue. Los hallazgos de este estudio se derivan de datos cualitativos y cuantitativos recolectados en 31 huertos familiares entre marzo y diciembre de 2009. El estudio documentó información sobre el manejo de plantas que crecen en huertos familiares, sus números, composición y usos. Las entrevistas en los núcleos familiares y la inspección de los huertos familiares mostraron que 73 especies fueron importantes para el sustento local. -

Widespread February Rains Improve Conditions Among Late-Planted Crops, but Most Early-Planted Crops in the South Are Lost

ZIMBABWE Food Security Outlook February - September 2018 Widespread February rains improve conditions among late-planted crops, but most early-planted crops in the south are lost KEY MESSAGES Current food security outcomes, February 2018 • Following below-normal rains during the first half of the cropping season, as well as a prolonged and abnormally dry and hot spell in January, widespread rains were received in February. The rains have resulted in the recovery of some late-planted crops which were at a critical wilting point. Unfortunately for most areas in the south and other parts of the country where crops were planted earlier, much of these crops had permanently wilted. The rains have also improved water and pasture conditions in most areas. National maize production for 2017-18 will most likely be below-average. • National maize supply is atypically above-average and is expected to remain so until the end of the current marketing year in March. This is mainly due to high crop production from last season. Significantly above-average national maize carry-over stocks are expected into the next marketing year (2018-19). After experiencing relatively stable prices during most of the current consumption year, maize grain price Source: FEWS NET FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible. IPC- increases became notable in late January. This has been attributed to compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but does not the dryness and anticipated poor harvests. However, maize prices necessarily reflect the consensus of national food security continue to be below last year and the average, a trend that is partners. -

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 19, No. 8

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 19, No. 8 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuzn198808 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zimbabwe News, Vol. 19, No. 8 Alternative title Zimbabwe News Author/Creator Zimbabwe African National Union Publisher Zimbabwe African National Union (Harare, Zimbabwe) Date 1988-08-00 Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe, South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1988 Source Northwestern University Libraries, L968.91005 Z711 v.19 Rights By kind permission of ZANU, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front. Description Editorial: 1. 2. Comment. Letters. Department of External Affairs — ZANU (PF). -

Rapid Market Assessment of Key Sectors for Women and Youth in Zimbabwe Apiculture Artisanal Mining Mopane Worms Horticulture

MARKET SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT FOR DECENT WORK MARKET SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT FOR DECENT WORK RAPID MARKET ASSESSMENT OF KEY SECTORS FOR WOMEN AND YOUTH IN ZIMBABWE APICULTURE ARTISANAL MINING MOPANE WORMS HORTICULTURE RAPID MARKET ASSESSMENT MARKET SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT FOR DECENT WORK OF KEY SECTORS FOR WOMEN AND YOUTH IN ZIMBABWE APICULTURE ARTISANAL MINING MOPANE WORMS HORTICULTURE Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published 2017 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publi- cations (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ISBN: 9789221309178 (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Factors Associated with Male Involvement in the Prevention Of

Makoni et al. BMC Public Health (2016) 16:331 DOI 10.1186/s12889-016-2939-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Factors associated with male involvement in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV, Midlands Province, Zimbabwe, 2015 - a case control study Annamercy Makoni1, Milton Chemhuru2, Cleopas Chimbetete1, Notion Gombe1, More Mungati1, Donewell Bangure1* and Mufuta Tshimanga1 Abstract Background: Uptake of and adherence to the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) interventions are a challenge to most women if there is no male partner involvement. Organizations which include the National AIDS Council and the Zimbabwe AIDS Prevention Project- University of Zimbabwe have been working towards mobilizing men for couple HIV testing and counseling (HTC) in antenatal care (ANC). In 2013, Midlands province had 19 % males who were tested together with their partners in ANC, an increase by 9 % from 2011. However, this improvement was still far below the national target, hence this study was conducted to determine the associated factors. Methods: A1:1 unmatched case control study was conducted. A case was a man who did not receive HIV testing and counseling together with his pregnant wife in ANC in Midlands province from January to June 2015. A control was a man who received HIV testing and counseling together with his pregnant wife in ANC in Midlands province from January to June 2015. Simple random sampling was used to select 112 cases and 112 controls. Epi Info statistical software was used to analyze data. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. Results: Independent factors that predicted male involvement in PMTCT were: having been previously tested as a couple (aOR) 0.22, 95 % CI = 0.12, 0.41) and having time to visit the clinic (aOR) 0.41, 95 % CI = 0.21, 0.80). -

National Survey of HIV and Syphilis Prevalence Among

AIDS & TB PROGRAMME 2013 i Contents Foreword i Acknowledgements iii Executive Summary iv Acronym v 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Country Profile 1 1.2 Background 2 2: OBJECTIVES 6 2.1 Broad Objectives 6 2.2 Specific objectives 6 3: METHOD 3.1 Survey design 6 3.2 Sampling 7 3.2.1 Sentinel population 7 3.2.2 Selection of survey population 7 3.2.3 Selection of sentinel surveillance sites 7 3.3 Sample size determination 7 3.6 Summary of Survey Operational Procedures 9 3.7 Laboratory procedures 10 3.7.1 Laboratory Methods 10 3.7.3 Quality Assurance of HIV Testing 11 3.8 Data entry and management 12 3.9 Data analysis 12 3.10 Overall quality assurance 12 4. RESULTS 13 4.1 Population characteristics 13 4.2 Distribution of HIV Prevalence in the fifty-three sentinel sites 17 4.3 Trends in HIV Prevalence 2002 -2012, For All Women 15-49 years in Nineteen Sentinel Sites 2002 -2012 29 4.4 HIV Prevalence and trends, Women age 15-24 years in Nineteen Sentinel Sites, 2002 -2012 36 4.5 Results of Syphilis 42 5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 44 5.1 Lessons Learnt 46 6. RECOMMENDATIONS 46 References 47 APPENDICES 48 Appendix 1: 2012 Sentinel Survey Sites Province and Sentinel Site Classification 48 Appendix 2: 2012 ANC Surveillance Form 50 Appendix 3: Laboratory HIV Parallel Testing Algorithm 53 Appendix 4: ANC Sentinel Surveillance Sites Since 2002 54 ii National Survey of HIV and Syphilis Prevalence among Women attending Antenatal Clinics in Zimbabwe 2012 List of Tables and Figures Tables Table 1: Summary of Zimbabwe Population in 2012 1 Table 2: Health and Socio-Economic