Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volební Geografie CDU/CSU – Situace Za Vlády Angely Merkelové

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra politologie Obor Politologie Volební geografie CDU/CSU – situace za vlády Angely Merkelové Bakalářská práce Monika Bělašková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Michal Pink, Ph.D. UČO: 397600 Obor: Politologie Imatrikulační ročník: 2011 Brno, 29. 4. 2014 1 Prohlášení o autorství práce Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma Volební geografie CDU/CSU – situace za vlády Angely Merkelové vypracovala samostatně a použila jen zdroje uvedené v seznamu literatury. V Brně, 29. 4. 2014 Podpis:............................................ 2 Poděkování Ráda bych zde poděkovala za užitečné rady a odborné připomínky vedoucímu práce Mgr. Michalu Pinkovi, Ph.D. 3 Anotace Tato práce se zabývá volebními výsledky Křesťansko-demokratické unie a Křesťansko-sociální unie ve Spolkové republice Německo od nástupu Angely Merkelové do kancléřského úřadu. Cílem je zjištění vývoje volební podpory křesťanských stran v průběhu vlády první ženské kancléřky, tedy od r. 2005 do posledních spolkových voleb r. 2013. Práce vychází ze zjišťování volební podpory strany na úrovni volebních obvodů pomocí volební geografie. Závěrečným výstupem je analýza volební podpory strany a nárůstu volebních zisků v průběhu vlády. Annotation This work deals with the election results of the Christian-Democratic Union and Christian-Social Union in the Federal Republic of Germany since Angela Merkel started in the Chanccellor´s Office. Primary aim is detection of the development of electoral support of Christian parties during the government of the first female Chancellor, so from year 2005 until the last Federal votes in the year 2013. The work is based on detection of the election support of the party at the degree of the electoral district using the electoral geography. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

Karte Der Wahlkreise Für Die Wahl Zum 18. Deutschen Bundestag

Karte der Wahlkreise für die Wahl zum 18. Deutschen Bundestag gemäß Anlage zu § 2 Abs. 2 des Bundeswahlgesetzes, die zuletzt durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 12. April 2012 (BGBl. I S. 518) geändert worden ist Nordfriesland Flensburg Schleswig- 2 Flensburg zu 2 1 zu 9 Grenze der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zu 15 Rendsburg- Kiel Eckernförde Landesgrenze 5 15 6 (auch Wahlkreisgrenze) zu 7 Plön 9 Dithmarschen 4 Rostock Vorpommern- Rügen Ostholstein Kreisgrenze Neu- münster 14 zu 3 Wahlkreisgrenze Vorpommern- zu 16 (auch Kreisgrenze) 3 Greifswald Segeberg Steinburg Lübeck Nordwestmecklenburg 8 Rostock Wahlkreisgrenze Stormarn 7 11 Pinneberg 17 Wittmund Schwerin 16 29 zu 25 Wilhelms- 10 haven 13 26 Bremerhaven 18 - 23 Saalekreis Kreisname zu 55 Herzogtum Aurich Stade Hamburg Lauenburg Mecklenburgische 24 Seenplatte Cuxhaven 12 Halle (Saale) Kreisfreie Stadt Emden Friesland 30 Wesermarsch Harburg 36 Ludwigslust- Rotenburg Parchim Lüneburg 72 Wahlkreisnummer Leer Osterholz (Wümme) Uckermark Ammerland 37 27 Oldenburg 57 (Oldenburg) 56 Bremen Prignitz Gebietsstand der Verwaltungsgrenzen: 30.09.2011 55 Rheinland-Pfalz: 01.01.2012 Delmen- horst 54 Ostprignitz- 35 28 Lüchow- Ruppin Verden Emsland 32 Oldenburg Uelzen Dannenberg Oberhavel 34 Barnim 25 Cloppenburg 58 33 Heidekreis Diepholz 44 66 Altmarkkreis Stendal Märkisch- Vechta 45 Salzwedel Oderland Nienburg Celle Havelland (Weser) 59 31 Gifhorn Berlin Grafschaft 38 75 - 86 Bentheim 40 43 Region Hannover 61 Brandenburg Osnabrück 134 Wolfsburg Potsdam an der Frankfurt 41 - 42 Havel (Oder) Minden- -

CULTURAL HERITAGE in MIGRATION Published Within the Project Cultural Heritage in Migration

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MIGRATION Published within the project Cultural Heritage in Migration. Models of Consolidation and Institutionalization of the Bulgarian Communities Abroad funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund © Nikolai Vukov, Lina Gergova, Tanya Matanova, Yana Gergova, editors, 2017 © Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum – BAS, 2017 © Paradigma Publishing House, 2017 ISBN 978-954-326-332-5 BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORE STUDIES WITH ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MIGRATION Edited by Nikolai Vukov, Lina Gergova Tanya Matanova, Yana Gergova Paradigma Sofia • 2017 CONTENTS EDITORIAL............................................................................................................................9 PART I: CULTURAL HERITAGE AS A PROCESS DISPLACEMENT – REPLACEMENT. REAL AND INTERNALIZED GEOGRAPHY IN THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MIGRATION............................................21 Slobodan Dan Paich THE RUSSIAN-LIPOVANS IN ITALY: PRESERVING CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS HERITAGE IN MIGRATION.............................................................41 Nina Vlaskina CLASS AND RELIGION IN THE SHAPING OF TRADITION AMONG THE ISTANBUL-BASED ORTHODOX BULGARIANS...............................55 Magdalena Elchinova REPRESENTATIONS OF ‘COMPATRIOTISM’. THE SLOVAK DIASPORA POLITICS AS A TOOL FOR BUILDING AND CULTIVATING DIASPORA.............72 Natália Blahová FOLKLORE AS HERITAGE: THE EXPERIENCE OF BULGARIANS IN HUNGARY.......................................................................................................................88 -

Twenty Years After the Iron Curtain: the Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010

Twenty Years after the Iron Curtain: The Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010 Assistant Professor at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic n November of last year, the Czech Republic commemorated the fall of the communist regime in I Czechoslovakia, which occurred twenty years prior.1 The twentieth anniversary invites thoughts, many times troubling, on how far the Czechs have advanced on their path from a totalitarian regime to a pluralistic democracy. This lecture summarizes and evaluates the process of democratization of the Czech Republic’s political institutions, its transition from a centrally planned economy to a free market economy, and the transformation of its civil society. Although the political and economic transitions have been largely accomplished, democratization of Czech civil society is a road yet to be successfully traveled. This lecture primarily focuses on why this transformation from a closed to a truly open and autonomous civil society unburdened with the communist past has failed, been incomplete, or faced numerous roadblocks. HISTORY The Czech Republic was formerly the Czechoslovak Republic. It was established in 1918 thanks to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his strong advocacy for the self-determination of new nations coming out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the World War I. Although Czechoslovakia was based on the concept of Czech nationhood, the new nation-state of fifteen-million people was actually multi- ethnic, consisting of people from the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia), Slovakia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia (today’s Ukraine), and approximately three million ethnic Germans. Since especially the Sudeten Germans did not join Czechoslovakia by means of self-determination, the nation- state endorsed the policy of cultural pluralism, granting recognition to the various ethnicities present on its soil. -

Bautzen – Geschichte Entdecken Budyšin – Stawizny Wotkrywać

Bautzen – Geschichte entdecken Budyšin – stawizny wotkrywać Viele Türme. Gute Aussicht. DIE Stadtverführer Mˇeš´canscyzawjednicy Stadtführungen und Reiseleitungen Abendliche r Stadtführungtembe Mai – Sep 0 Uhr um 19.0 Hauptmarkt 4 | 02625 Bautzen Telefon 0 35 91-48 66 18 | Telefax 0 35 91-48 66 20 www.stadtverfuehrer-bautzen.de [email protected] 365 Tage im Jahr in Bautzen für Sie erreichbar! Gruppenführung, Stadtverführung, Reiseleitung... z.B. »Bautzen is(s)t scharf« Stadtführung durch die Stadt des Senfes, allerlei wissens- wertes rund um das kleine Korn mit der großen Wirkung beim Rundgang durch das Senfmuseum… Fleischmarkt 5 · 02625 Bautzen · Telefon: 03591 597118 · www.bautzner.de …daran anschließend kulinarische Gaumenfreuden in der Schloßstraße 3 · 02625 Bautzen · Tel. 03591 598015 · www.senf-stube.de Die über 1.000-jährige Stadt der Türme und der Sorben lädt ein „Märchenhaft“ nennen Bewunderer die alte Stadt Bautzen, mit ihren vielen Türmen, den Bastionen, Toren und Mauern. Bischof Thietmar von Merseburg war es, der 1002 in seiner Chronik erst- malig die „Civitas Budusin“ erwähnte. Denn gerade kämpfte das frühe deutsche Reich mit dem polnischen Herzog Boleslaw um diesen fruchtbaren Landstrich und die Burg hoch auf dem Granitfelsen. Lange zuvor schon lebten hier Menschen, reiche Funde aus der Ur- und Früh- geschichte belegen dies für Bautzen und die Oberlausitz. Alte Handelsstraßen, allen voran die via regia, brachten Fortschritt und Wohlstand, nicht selten auch Not und Verderben. Als Jahrhunderte lang „Nebenland der böhmischen Krone“ wechselten hier die Herrscher, ließen Bautzen und die Lausitz zu Brandenburg, Meißen, Polen und zu Böhmen gehören. Von einer Zugehörigkeit gar zu Ungarn kündet noch heute das König-Matthias-Denkmal am Burgturm. -

Béatrice Knerr (Ed.) Transfers from International Migration

U_IntLabMig8_neu_druck 17.12.12 08:19 Seite 1 8 Béatrice Knerr (Ed.) Over the early 21st century the number of those living in countries in which they were not born has strongly expanded. They became international mi- grants because they hope for jobs, livelihood security, political freedom, or a safe haven. Yet, while the number of those trying to settle in richer coun- tries is increasing, entry hurdles mount up, and host countries become more selective. While low-skilled migrants meet rejection, highly qualified are welcome. All this hold significant implications for the countries and families the migrants come from, even more so as most of them keep close relations to their origin, and many return after a longer or shorter period of time. Some settle down comfortably, others struggle each day. Some return to their home country, others stay for good. Some loose connection to rel- atives and friends, others support them by remittances for livelihood secu- International Labor Migration/// Series edited by Béatrice Knerr 8 rity and investment. In any case, most of these international migrants are – explicitly or not–involved in various stabilization strategies, be it by house- hold/family agreements, government efforts to attract valuable human capital, or sheer expectations by different actors. Transfers from This volume intends to span this spectrum by presenting impressive case studies covering essential facets of international migrants’ relationships International Migration: within their families and societies of origin. Each case study represents an essential type of linkage, starting with financial remittances, for livelihood security or investment purposes, over social remittances, up to political in- fluence of the Diaspora, covering the family/household, community and A Strategy of Economic and Social Stabilization country level. -

Young Czechs' Perceptions of the Velvet Divorce and The

YOUNG CZECHS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE VELVET DIVORCE AND THE MODERN CZECH IDENTITY By BRETT RICHARD CHLOUPEK Bachelor of Science in Geography Bachelor of Science in C.I.S. University of Nebraska Kearney Kearney, NE 2005 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2007 YOUNG CZECHS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE VELVET DIVORCE AND THE MODERN CZECH IDENTITY Thesis Approved: Reuel Hanks Dr. Reuel Hanks (Chair) Dale Lightfoot Dr. Dale Lightfoot Joel Jenswold Dr. Joel Jenswold Dr. A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Reuel Hanks for encouraging me to pursue this project. His continued support and challenging insights into my work made this thesis a reality. Thanks go to my other committee members, Dr. Dale Lightfoot and Dr. Joel Jenswold for their invaluable advice, unique expertise, and much needed support throughout the writing of my thesis. A great deal of gratitude is due to the faculties of Charles University in Prague, CZ and Masaryk University in Brno, CZ for helping administer student surveys and donating their valuable time. Thank you to Hana and Ludmila Svobodova for taking care of me over the years and being my family away from home in the Moravské Budejovice. Thanks go to Sylvia Mihalik for being my resident expert on all things Slovak and giving me encouragement. Thank you to my grandmother Edith Weber for maintaining ties with our Czech relatives and taking me back to the ‘old country.’ Thanks to all of my extended family for remembering our heritage and keeping some of its traditions. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

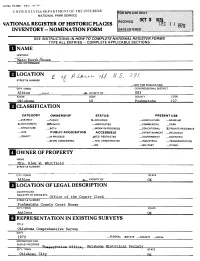

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

rnnNo. 10-300 REV. (9/77; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC "Mato/Kosvk/House___ ______________________________________ AND/ORTSOMMOfi LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Albion VICINITY OF 003 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Oklahoma 40 Puffhmataha 127 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) .2EPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Qlen W. Whltfleld STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Albion VICINITY OF OK LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Office of the County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Pushmataha County Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Antlers OK REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Oklahoma Comprehensive Survey DATE 1979 —FEDERAL JXSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Oklahoma Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Oklahoma Citv OK DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED JiUNALTERED 2LORIGINALSITE X_GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Mato Kosyk house is a small one-story, rectangular, white frame building located about three-quarters of a mile west of Albion on a gravel road. It is not entirely visible from the road, and access to it is by a private driveway leading south from the road, then west to the house lot. -

MOHSEN MOSTAFAVI MOBASHER, the Iranian Diaspora: Challenges, Negotiations, and Transformations (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018)

Mashriq & Mahjar 7, no. 1 (2020), 86–89 ISSN 2169-4435 MOHSEN MOSTAFAVI MOBASHER, The Iranian Diaspora: Challenges, Negotiations, and Transformations (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018). 284 pp. $45.00 cloth. REVIEWED BY SAHAR RAZAVI, California State University, Sacramento, email: mailto:[email protected] Mobasher’s volume on the Iranian diaspora offers insights into a variety of diasporic Iranian communities, all in the West with the exception of one study on the Iranian experience in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The book aims to expand existing knowledge about Iranians in diaspora, expanding the field beyond previous studies which were small in number and limited in scope, and thus not generalizable to larger populations. While the chapters of the book are collected in a volume presenting a range of experiences in this particular community, taken together the book offers a glimpse into what Mobasher calls a “unique” identity in which the country of origin and the country of destination combine to form a new way to be Iranian. This new kind of “Iranianness” is in a constant state of construction and reconstruction as Iranians navigate the sometimes precarious social and political landscapes in which they find themselves. Sahar Sadeghi’s study on the sense of belonging and foreignness of first- and second-generation Iranians in Germany confronts segmented assimilation theory, which suggests that by the second generation, immigrants’ acculturation to the host country takes on the existing social stratification in their new societies. Iranians in Europe generally have high levels of human capital, including wealth and educational achievement, but this has not led to greater levels of integration in places like Germany, where marginalization from the opportunity networks enjoyed by “ethnic” Germans. -

Bstu / State Security. a Reader on the GDR

Daniela Münkel (ed.) STATE SECURITY A READER ON THE GDR SECRET POLICE Daniela Münkel (ed.) STATE SECURITY A READER ON THE GDR SECRET POLICE Imprint Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic Department of Education and Research 10106 Berlin [email protected] Photo editing: Heike Brusendorf, Roger Engelmann, Bernd Florath, Daniela Münkel, Christin Schwarz Layout: Pralle Sonne Originally published under title: Daniela Münkel (Hg.): Staatssicherheit. Ein Lesebuch zur DDR-Geheimpolizei. Berlin 2015 Translation: Miriamne Fields, Berlin A READER The opinions expressed in this publication reflect solely the views of the authors. Print and media use are permitted ON THE GDR SECRET POLICE only when the author and source are named and copyright law is respected. token fee: 5 euro 2nd edition, Berlin 2018 ISBN 978-3-946572-43-5 6 STATE SECURITY. A READER ON THE GDR SECRET POLICE CONTENTS 7 Contents 8 Roland Jahn 104 Arno Polzin Preface Postal Inspection, Telephone Surveillance and Signal Intelligence 10 Helge Heidemeyer The Ministry for State Security and its Relationship 113 Roger Engelmann to the SED The State Security and Criminal Justice 20 Daniela Münkel 122 Tobias Wunschik The Ministers for State Security Prisons in the GDR 29 Jens Gieseke 130 Daniela Münkel What did it Mean to be a Chekist? The State Security and the Border 40 Bernd Florath 139 Georg Herbstritt, Elke Stadelmann-Wenz The Unofficial Collaborators Work in the West 52 Christian Halbrock 152 Roger Engelmann