MOHSEN MOSTAFAVI MOBASHER, the Iranian Diaspora: Challenges, Negotiations, and Transformations (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

Internal Diversity

GLOBAL DIVERSITIES Internal Diversity Iranian Germans Between Local Boundaries and Transnational Capital Sonja Moghaddari mpimmg Global Diversities Series Editors Steven Vertovec Department of Socio-Cultural Diversity Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity Göttingen, Germany Peter van der Veer Department of Religious Diversity Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity Göttingen, Germany Ayelet Shachar Department of Ethics, Law, and Politics Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity Göttingen, Germany Over the past decade, the concept of ‘diversity’ has gained a leading place in academic thought, business practice, politics and public policy across the world. However, local conditions and meanings of ‘diversity’ are highly dissimilar and changing. For these reasons, deeper and more com- parative understandings of pertinent concepts, processes and phenomena are in great demand. This series will examine multiple forms and configu- rations of diversity, how these have been conceived, imagined, and repre- sented, how they have been or could be regulated or governed, how different processes of inter-ethnic or inter-religious encounter unfold, how conflicts arise and how political solutions are negotiated and prac- ticed, and what truly convivial societies might actually look like. By com- paratively examining a range of conditions, processes and cases revealing the contemporary meanings and dynamics of ‘diversity’, this series will be a key resource for students and professional social scientists. It will repre- sent a landmark within a field that has become, and will continue to be, one of the foremost topics of global concern throughout the twenty-first century. -

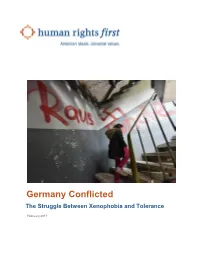

Germany Conflicted the Struggle Between Xenophobia and Tolerance

Germany Conflicted The Struggle Between Xenophobia and Tolerance February 2017 ON HUMAN RIGHTS, the United States must be a beacon. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to Research for this report was conducted by Susan Corke look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. and Erika Asgeirsson at Human Rights First and a team from Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s a the University of Munich: Heather Painter, Britta vital national interest. America is strongest when our policies Schellenberg, and Klaus Wahl. Much of the research and actions match our values. consisted of interviews and consultations with human rights Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and action activists, government officials, national and international organization that challenges America to live up to its ideals. NGOs, multinational bodies, faith and interfaith groups, We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle scholars, and attorneys. We greatly appreciate their for human rights so we press the U.S. government and assistance and expertise. Rebecca Sheff, the former legal private companies to respect human rights and the rule of fellow with the antisemitism and extremism team, also law. When they don’t, we step in to demand reform, contributed to the research for this report during her time at accountability, and justice. Around the world, we work where Human Rights First. We are grateful for the team at Dechert we can best harness American influence to secure core LLP for their pro bono research on German law. At Human freedoms. Rights First, thanks to Sarah Graham for graphics and design; Meredith Kucherov and David Mizner for editorial We know that it is not enough to expose and protest injustice, assistance; Dora Illei for her research assistance; and so we create the political environment and policy solutions the communications team for their work on this report. -

Iranians in Sweden

Article • DOI: 10.1515/njmr-2018-0013 NJMR • 8(2) • 2018 • 73-81 A FRAGMENTED DIASPORA: Iranians in Sweden Abstract The notion of diaspora generally indicates achievements: creating a home Shahram Khosravi* outside the homeland, entrepreneurship, the establishment of local and global networks, new organisations, media and spatial as well as social Stockholm University, Sweden mobility. In studies of Iranian diaspora, a rosy picture of ‘super successful’ Iranians has often obscured other aspects of the diaspora — failure, conflicts, internal exclusion and fragmentation of the group along various lines, such as ideologies, class, gender, local identification and cause of migration. Through ethnographic vignettes of the Iranian migrants in Sweden, this article demonstrates the segmentation, hybridity and complexity of the experiences of the diaspora. Avoiding the language of generalisation and by focussing instead on particular histories and individual circumstances, it reveals the diversity, disintegration and contradictions within what has been assumed to be a homogeneous and static diaspora. Keywords Sweden • Iranians • Segmented diaspora • Internal diversity • Refugees Received 28 November 2016; Accepted: 23 November 2017 Introduction to bring a Turkish ghari to conduct the ceremony. The Turkish ghari’s recitation of the Quran and his presentation were unfamiliar and were I start with an ethnographic description of a funeral ceremony at a cut short by one of Bahram’s daughters, who started to read Persian small cemetery beside a church in Northwestern Stockholm on a cold poems from Hafez (a 14th -century poet). Finally, coordination of the snowy Wednesday in March 1998. It was the funeral for Bahram, lowering of the coffin was conducted in three languages: Persian, who had passed away a week earlier at the age of 65 years. -

The Iranian Diaspora: Challenges, Negotiations, and Transformations by Mohsen Mostafavi Mobasher (Review)

The Iranian Diaspora: Challenges, Negotiations, and Transformations by Mohsen Mostafavi Mobasher (review) Sahar Razavi Mashriq & Mahjar: Journal of Middle East and North African Migration Studies, Volume 7, Number 1, 2020, (Review) Published by Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/776267/summary [ Access provided at 29 Sep 2021 09:26 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Mashriq & Mahjar 7, no. 1 (2020) MOHSEN MOSTAFAVI MOBASHER, The Iranian Diaspora: Challenges, Negotiations, and Transformations (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018). 284 pp. $45.00 cloth. REVIEWED BY SAHAR RAZAVI, California State University, Sacramento, email: mailto:[email protected] Mobasher’s volume on the Iranian diaspora offers insights into a variety of diasporic Iranian communities, all in the West with the exception of one study on the Iranian experience in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The book aims to expand existing knowledge about Iranians in diaspora, expanding the field beyond previous studies which were small in number and limited in scope, and thus not generalizable to larger populations. While the chapters of the book are collected in a volume presenting a range of experiences in this particular community, taken together the book offers a glimpse into what Mobasher calls a “unique” identity in which the country of origin and the country of destination combine to form a new way to be Iranian. This new kind of “Iranianness” is in a constant state of construction and reconstruction as Iranians navigate the sometimes precarious social and political landscapes in which they find themselves. Sahar Sadeghi’s study on the sense of belonging and foreignness of first- and second-generation Iranians in Germany confronts segmented assimilation theory, which suggests that by the second generation, immigrants’ acculturation to the host country takes on the existing social stratification in their new societies. -

Eastern Germany, Iranian Refugees Surprise Pastors with Their Interest in Christianity

[ EVANGELISM ] The Other Iranian Revolution In ‘godless’ eastern Germany, Iranian refugees surprise pastors with their interest in Christianity. By Matthias Pankau and Uwe Siemon-Netto OD MUST HAVE BEEN LAUGHING up his sleeve,” muses Jobst Schöne. The retired bishop of the Inde- pendent Lutheran Church in Germany is applying a German paraphrase of Psalm 2:4 to the baptism of seven former Muslims from Iran. Early Easter morn- ing, the seven were baptized in the Berlin parish where Schöne serves as associate pastor. The baptisms were an emblem of something bigger—a nationwide surge of such conversions in several denominations and a spate of reports of Muslims seeing Jesus in their dreams. But Martin Luther’s Bible translation, now nearly 500 Some of the converts at St. Mary’s were them- years old, also played an important role in their story. selves persecuted before fleeing to Germany, The group baptism happened at an unsettling time for European Christians. During Lent, now home to the largest Iranian community in Gradical Muslims handed out large numbers of Qur’ans on street corners and announced Western Europe, numbering 150,000. plans to distribute 25 million German-language copies of their holy book in order to win “These refugees are taking unimaginable Germans to their faith. But on the night before Easter, some 150 worshipers filed silently risks to live their Christian faith,” says Mar- into St. Mary’s Church in the Zehlendorf district of Berlin to witness conversions in the tens, who ministers to one of Germany’s most opposite direction. dynamic parishes, which has grown from Until midnight, the sanctuary was dark. -

The Lasting Legacy of the Red Army Faction

WEST GERMAN TERROR: THE LASTING LEGACY OF THE RED ARMY FACTION Christina L. Stefanik A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Kristie Foell, Advisor Dr. Christina Guenther Dr. Jeffrey Peake Dr. Stefan Fritsch ii ABSTRACT Dr. Kristie Foell, Advisor In the 1970s, West Germany experienced a wave of terrorism that was like nothing known there previously. Most of the terror emerged from a small group that called itself the Rote Armee Fraktion, Red Army Faction (RAF). Though many guerrilla groupings formed in West Germany in the 1970s, the RAF was the most influential and had the most staying-power. The group, which officially disbanded in 1998, after five years of inactivity, could claim thirty- four deaths and numerous injuries The death toll and the various kidnappings and robberies are only part of the RAF's story. The group always remained numerically small, but their presence was felt throughout the Federal Republic, as wanted posters and continual public discourse contributed to a strong, almost tangible presence. In this text, I explore the founding of the group in the greater West German context. The RAF members believed that they could dismantle the international systems of imperialism and capitalism, in order for a Marxist-Leninist revolution to take place. The group quickly moved from words to violence, and the young West German state was tested. The longevity of the group, in the minds of Germans, will be explored in this work. -

The Role of Different Forms of Capital in the Status Passage of Documented Iranian Migrants in Ankara, Turkey

TRANSFORMING CONSTRAINTS INTO STRATEGIES: THE ROLE OF DIFFERENT FORMS OF CAPITAL IN THE STATUS PASSAGE OF DOCUMENTED IRANIAN MIGRANTS IN ANKARA, TURKEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY YASEMİN AKİS KALAYLIOĞLU IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY MARCH 2016 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ________________________ Prof. Dr. Meliha ALTUNIŞIK Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________ Prof. Dr. Sibel KALAYCIOĞLU Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ Prof. Dr. Helga RITTERSBERGER-TILIÇ Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Gülay TOKSÖZ (ANKARA UNI, LAB. ECON) ________________ Prof. Dr. Helga RITTERSBERGER-TILIÇ (METU, SOC) ________________ Assoc. Prof. F. Umut BEŞPINAR (METU, SOC) ________________ Assoc. Prof. Didem DANIŞ (GALATASARAY UNI, SOC)________________ Assist. Prof. Çağatay TOPAL (METU, SOC) ________________ PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: YASEMİN AKİS KALAYLIOĞLU Signature : iii ABSTRACT TRANSFORMING CONSTRAINTS INTO STRATEGIES: THE ROLE OF DIFFERENT FORMS OF CAPITAL IN THE STATUS PASSAGE OF DOCUMENTED IRANIAN MIGRANTS IN ANKARA, TURKEY Akis Kalaylıoğlu, Yasemin Ph.D., Department of Sociology Supervisor: Prof. -

The Origin of the Different Waves of Iranian Migration in France

Cultural and Religious Studies, August 2016, Vol. 4, No. 8, 469-487 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Origin of the Different Waves of Iranian Migration in France Nader Vahabi School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (CADIS) in Paris, University of Toulouse (Rural Dynamics), France From the knowledge exile of the 19th century, the profile changed towards the political refugee in 1908. French was then recognized as the official language in administration. Iranian migration later took on another dimension after the 1953 Coup, a politicization that reached a peak with the arrival in Paris of Khomeini on August 2, 1978. In spite of this migratory tradition, about 4,000 persons before the revolution, the majority being from the political and financial elite, these migratory flows amplified in the middle of the 1980s, in such a way that at the end of December 2014, there were 31,000 Iranians in France. This new phase which included four waves, from a sociological point of view, can be called the diasporaisation of Iranian migration. The socio-economic profile goes from the urban elite: lawyers, officials, journalists, teachers, doctors, nurses, magistrates, military officials, company directors, political exiles, etc., to artisans such as shopkeepers, garage owners, building contractors… and finally from the skilled labourer, on through to unskilled workers in building, restauration or removals. Keywords: Iranian diaspora, migratory flows, four waves of migration, socio-economic profile Among the few studies on the subject, rare are those that go back to the 19th century1. Very often, the arrival of Iranians in France is studied as from the 1920s, when, under the regime of Rezâ Châh Pahlevi, many were sent abroad within the framework of pioneering legislation on the matter2. -

How Institutional Arrangements Decide the Fates of Small Nations; Case Studies from Central Europe

THE MYTH OF SELF-DETERMINATION: HOW INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS DECIDE THE FATES OF SMALL NATIONS; CASE STUDIES FROM CENTRAL EUROPE BY Copyright 2008 Matthew Wayne Slaboch Submitted to the graduate degree program in Political Science and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Ronald A. Francisco _ Chairperson John J. Kennedy _ Eric A. Hanley _ Date Defended: July 16, 2008 The Thesis Committee for Matthew Wayne Slaboch certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: THE MYTH OF SELF-DETERMINATION: HOW INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS DECIDE THE FATES OF SMALL NATIONS; CASE STUDIES FROM CENTRAL EUROPE Committee: Ronald A. Francisco Chairperson John J. Kennedy Eric A. Hanley Date approved: July 24, 2008 ii Abstract The number of stateless ethno-national groups exceeds the number of groups that exercise sovereignty over the lands in which they live. The purpose of this thesis is to determine what makes one group more likely than another to attain statehood. The study begins with a review of literature that focuses on nationalism. From this literature review are derived three hypotheses as to how groups gain independence. Using comparative case studies from Central Europe, these hypotheses are tested against available evidence. The findings of these case studies suggest that certain institutional arrangements –namely, territorial autonomy within a federal system— allow independence movements to succeed. In light of the conclusions reached, -

Connections October 2004 the Journal of the WEA Missions Commission Letter to Our Readers 2 Editorials from the Heart and Mind of the Editor, Willliam D

Connections October 2004 The Journal of the WEA Missions Commission Letter to Our Readers 2 Editorials From the Heart and Mind of the Editor, Willliam D. Taylor 5 Europe an Authentic Less- Reached Mission Field, K. Rajendran 8 Welcome to Kees van der Wilden, William D. Taylor 10 Feature Articles Mission to Europe: Troublesome, Challenge or Blessing, Kees van der Wilden 15 Living as People of HOPE, Jeff Fountain 21 Europe, a Riddle Wrapped in an Enigma, Cees Verharen 28 The Turkish Church and The European Union, Cees Verharen 41 Mending a Torn Society - Hungary, Jan van Butselaar 48 Missional Proverbs Proverbial Perespectives of Europe, Stan Nussbaum 50 Global Reports for Global Impact Report from New Zealand and “Taup4ward”, Gordon Stanley 52 Missions Interlink-Australia: A New Look for a New Generation, Phil Douglas 54 Global Faces, A Membercare Report, Kelly O’ Donnell 56 TIE Report from Europe, Derek Green 59 Internet Based Missionary Training: An International Missionary Training Network Report, Jon Lewis 61 Refugee Highway Partnership: European Refugee Network Expansion, Mark Orr 63 Book Reviews IntroducingWorld Missions, Scott Moreau, Gary, R. Corwin, Gary B. McGee, Reviewed by Steve Hoke 65 Whose Religion is Christianity? Lamin Sanneh, Reviewed by Cathy Ross 68 Member Care for Missionaries: A Practical Guide for Senders, Reviewed WEA Missions Commission by Hartmut Stricker 70 #1-300/118, Arul colony, ECIL post, Christianity at the Religious Roundtable, Timothy C. Tennet, Reviewed Hyderabad - 500062. by Tai - Woong Lee A. P., INDIA 72 www.globalmission.org Hope for Europe, Thomas Schirrmacher, Reviewed by Klaus Muller 74 Dr. William D. -

Localizing Ashkenazic Jews to Primeval Villages in the Ancient Iranian Lands of Ashkenaz

GBE Localizing Ashkenazic Jews to Primeval Villages in the Ancient Iranian Lands of Ashkenaz Ranajit Das1,2, Paul Wexler3, Mehdi Pirooznia4, and Eran Elhaik1,* 1Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK 2Manipal Centre for Natural Sciences (MCNS), Manipal University, Manipal, Karnataka, India 3Department of Linguistics, Tel Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel 4Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University *Corresponding author: E-mail: e.elhaik@sheffield.ac.uk. Accepted: February 29, 2016 Downloaded from Abstract The Yiddishlanguageisover1,000yearsoldandincorporatesGerman,Slavic,andHebrewelements.TheprevalentviewclaimsYiddish http://gbe.oxfordjournals.org/ has a German origin, whereas the opposing view posits a Slavic origin with strong Iranian and weak Turkic substrata. One of the major difficulties in deciding between these hypotheses is the unknown geographical origin of Yiddish speaking Ashkenazic Jews (AJs). An analysis of 393 Ashkenazic, Iranian, and mountain Jews and over 600 non-Jewish genomes demonstrated that Greeks, Romans, Iranians,andTurksexhibitthehighestgeneticsimilaritywithAJs.TheGeographicPopulationStructureanalysislocalizedmostAJsalong major primeval trade routes in northeastern Turkey adjacent to primeval villages with names that may be derived from “Ashkenaz.” IranianandmountainJewswerelocalizedalongtraderoutesontheTurkey’seasternborder.Lossofmaternalhaplogroupswasevident in non-Yiddish speaking AJs. Our results suggest that AJs originated from a Slavo-Iranian