“Assimulation” in the Land of Ten-Thousand Iranian Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tajik Ethnicity in Historical Perspective

Tajik Ethnicity in Historical Perspective Dedicated to the memory of Dr. Muhammad Asemi by Iraj Bashiri Copyright 1998 Introduction 1 The present study is part of an ongoing project on aspects of Tajik identity. It views Tajik ethnicity diachronically as well as synchronically. As part of its diachronic 1 This paper was delivered for the first time at the conference on Society, Language, and Culture in Post- Communist Russia, the Other Former Republics of the Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe, Texas Tech University, April 1998. exploration, it examines the Central Asian documents of the time, notably Hudud al- 'Alam. It also examines Ibn Howqal's Surat al-Arz, Clavijo's account of his journey to Samarqand, and the reports of early Russian explorers detailing the involvement of the Turks in the region before the advent of the Soviets. The synchronic exploration deals with the dynamics of assimilation evidenced in the diachronic analysis. Using the data provided by the Soviet Tajik Encyclopedia regarding territorial divisions, ethnic mix, and population numbers for more than one thousand villages, it hypothesizes that many Tajik villages in the Kuhistan are in a transitional stage. From the data, it seems that on their way to become Uzbek villages, Tajik villages pass through three stages: primarily Tajik, Tajik-Uzbek, and primarily Uzbek. It is important to note at the very start, that this study is in no way conclusive. As far as the diachronic aspect of the study is concerned, there is a wealth of materials in Persian and Turkish languages that awaits examination. Regarding the synchronic aspect, too, a comparison between early 20th century Russian reports and the 1980's census is not sufficient. -

Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3

1. The Stevedore’s Serenade (Edelstein-Gordon-Ellington) 2. La Dee Doody Doo (Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3. A Blues Serenade (Parish-Signorelli-Grande-Lytell) 4. Love In Swingtime (Lambert-Richards-Mills) 5. Please Forgive Me (Ellington-Gordon-Mills) 6. Lambeth Walk (Furber-Gay) 7. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 8. Hip Chic (Ellington) 9. Buffet Flat (Ellington) 10. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 11. There’s Something About An Old Love (Mills-Fien-Hudson) 12. The Jeep Is Jumpin’ (Ellington-Hodges) 13. Krum Elbow Blues (Ellington-Hodges) 14. Twits And Twerps (Ellington-Stewart) 15. Mighty Like The Blues (Feather) 16. Jazz Potpourri (Ellington) 17. T. T. On Toast lEllington-Mills) 18. Battle Of Swing (Ellington) 19. Portrait Of The Lion (Ellington) 20. (I Want) Something To Live For (Ellington-Strayhorn) 21. Solid Old Man (Ellington) 22. Cotton Club Stomp (Carney-Hodges-Ellington) 23. Doin’The Voom Voom (Miley-Ellington) 24. Way Low (Ellington) 25. Serenade To Sweden (Ellington) 26. In A Mizz (Johnson-Barnet) 27. I’m Checkin’ Out, Goo’m Bye (Ellington) 28. A Lonely Co-Ed (Ellington) 29. You Can Count On Me (Maxwell-Myrow) 30. Bouncing Buoyancy (Ellington) 31. The Sergeant Was Shy (Ellington) 32. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 33. Little Posey (Ellington) 34. I Never Felt This Way Before (Ellington) 35. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 36. Tootin Through The Roof (Ellington) 37. Weely (A Portrait Of Billy Strayhorn) (Ellington) 38. Killin’ Myself (Ellington) 39. Your Love Has Faded (Ellington) 40. Country Gal (Ellington) 41. Solitude (Ellington-De Lange-Mills) 42. Stormy Weather (Arlen-Köhler) 43. -

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

CIC Diversity Colume 6:2 Spring 2008

VOLUME 6:2 SPRING 2008 Guest Editor The Experiences of Audrey Kobayashi, Second Generation Queen’s University Canadians Support was also provided by the Multiculturalism and Human Rights Program at Canadian Heritage. Spring / printemps 2008 Vol. 6, No. 2 3 INTRODUCTION 69 Perceived Discrimination by Children of A Research and Policy Agenda for Immigrant Parents: Responses and Resiliency Second Generation Canadians N. Arthur, A. Chaves, D. Este, J. Frideres and N. Hrycak Audrey Kobayashi 75 Imagining Canada, Negotiating Belonging: 7 Who Is the Second Generation? Understanding the Experiences of Racism of A Description of their Ethnic Origins Second Generation Canadians of Colour and Visible Minority Composition by Age Meghan Brooks Lorna Jantzen 79 Parents and Teens in Immigrant Families: 13 Divergent Pathways to Mobility and Assimilation Cultural Influences and Material Pressures in the New Second Generation Vappu Tyyskä Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee 84 Visualizing Canada, Identity and Belonging 17 The Second Generation in Europe among Second Generation Youth in Winnipeg Maurice Crul Lori Wilkinson 20 Variations in Socioeconomic Outcomes of Second Generation Young Adults 87 Second Generation Youth in Toronto Are Monica Boyd We All Multicultural? Mehrunnisa Ali 25 The Rise of the Unmeltable Canadians? Ethnic and National Belonging in Canada’s 90 On the Edges of the Mosaic Second Generation Michele Byers and Evangelia Tastsoglou Jack Jedwab 94 Friendship as Respect among Second 35 Bridging the Common Divide: The Importance Generation Youth of Both “Cohesion” and “Inclusion” Yvonne Hébert and Ernie Alama Mark McDonald and Carsten Quell 99 The Experience of the Second Generation of 39 Defining the “Best” Analytical Framework Haitian Origin in Quebec for Immigrant Families in Canada Maryse Potvin Anupriya Sethi 104 Creating a Genuine Islam: Second Generation 42 Who Lives at Home? Ethnic Variations among Muslims Growing Up in Canada Second Generation Young Adults Rubina Ramji Monica Boyd and Stella Y. -

Donor Report Inside P R O F E S S O R J O H N W O O D I N Photography

Non Profit Org THE UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS US Postage 320 South Broad Street PAID Philadelphia, PA 19102 Philadelphia, PA UArts.edu Permit No. 1103 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS edg e THE edge MAGAZINE OF T HE U NIVERSITY OF THE A RTS FALL FALL 2013 2013 NO . 11 Donor Report Inside PROFESSOR JOHN WOODIN photography S EAN T. B UFFING T ON PRESIDENT L UCI ll E H UG H E S PUBLISHER VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT P AU L F. H EA LY EDITOR ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT OF UNIVERSITY COMMUNICATIONS E LY ss E R ICCI B FA ’ 0 8 ART DIRECTOR & DESIGNER J AME S M AU R E R PRODUCTION MANAGER D ANA R O dr IGUEZ CONTRIBUTING EDITOR CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS S T EVE B E L KOWI T Z J A S ON C H EN B FA ’ 0 8 S AMUE L N AGE L M IC H AE L S P ING L E R S T EVE S tr EI S GU th B FA ’ 0 9 th EY B K LYN J O H N W OO D IN CONTRIBUTING WRITERS A NI S A H AI D A R Y P AU L F. H EA LY E L I S E J U S KA C A th E R INE G UN th E R K O D A T S A R A M AC D ONA ld D ANA R O dr IGUEZ J OANNA S UNG L AU R EN V I ll ANUEVA COVER IMAGE S T EVE B E L KOWI T Z , 2 0 1 1 POSTMASTER : SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO edge c/o University Communications, The University of the Arts, 320 S. -

Arts, Culture and Media 2010 a Creative Change Report Acknowledgments

Immigration: Arts, Culture and Media 2010 A Creative Change Report Acknowledgments This report was made possible in part by a grant from Unbound Philanthropy. Additional funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Ford Foundation, Four Freedoms Fund, and the Open Society Foundations supports The Opportunity Agenda’s Immigrant Opportunity initiative. Starry Night Fund at Tides Foundation also provides general support for The Opportunity Agenda and our Creative Change initiative. Liz Manne directed the research, and the report was co-authored by Liz Manne and Ruthie Ackerman. Additional assistance was provided by Anike Tourse, Jason P. Drucker, Frances Pollitzer, and Adrian Hopkins. The report’s authors greatly benefited from conversations with Taryn Higashi, executive director of Unbound Philanthropy, and members of the Immigration, Arts, and Culture Working Group. Editing was done by Margo Harris with layout by Element Group, New York. This project was coordinated by Jason P. Drucker for The Opportunity Agenda. We are very grateful to the interviewees for their time and willingness to share their views and opinions. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works closely with social justice organizations, leaders, and movements to advocate for solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and promising solutions; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

Iranian-American's Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination

Interpersona | An International Journal on Personal Relationships interpersona.psychopen.eu | 1981-6472 Articles Iranian-American’s Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination: Differences Between Muslim, Jewish, and Non-Religious Iranian-Americans Shari Paige* a, Elaine Hatfield a, Lu Liang a [a] University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA. Abstract Recent political events have created a political and social climate in the United States that promotes prejudice against Middle Eastern, Iranian, and Muslim peoples. In this study, we were interested in investigating two major questions: (1) How much ethnic harassment do Iranian-American men and women from various religious backgrounds (Muslim, Jewish, or no religious affiliation at all) perceive in their day-to-day interactions? (2) To what extent does the possession of stereotypical Middle Eastern, Iranian, or Muslim traits (an accent, dark skin, wearing of religious symbols, traditional garb, etc.) spark prejudice and thus the perception of ethnic harassment? Subjects were recruited from two very different sources: (1) shoppers at grocery stores in Iranian-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and (2) a survey posted on an online survey site. A total of 338 Iranian-Americans, ages 18 and older, completed an in-person or online questionnaire that included the following: a request for demographic information, an assessment of religious preferences, a survey of how “typically” Iranian-American Muslim or Iranian-American Jewish the respondents’ traits were, and the Ethnic Harassment Experiences Scale. One surprise was that, in general, our participants reported experiencing a great deal of ethnic harassment. As predicted, Iranian-American Muslim men perceived the most discrimination—far more discrimination than did American Muslim women. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 30, 2019 to Sun. October 6, 2019

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 30, 2019 to Sun. October 6, 2019 Monday September 30, 2019 3:00 PM ET / 12:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT The Big Interview Tom Green Live Olivia Newton-John - Still with the magical voice, the star of Grease sits down with Dan and we Cheech & Chong - It’s double the funny on Tom Green Live as Tom sits down with one of the go backstage before her sold out Las Vegas performance. premiere comedy duos of all time: Cheech & Chong! Bringing their patented stoned-out humor to best-selling albums and feature films, Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong lit up the nation with 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT laughter, then carved out individual careers as TV actors on dramas and sitcoms. The Top Ten Revealed Epic Songs of ‘78 - Find out which Epic Songs of ‘78 make our list as rock experts like Steven Adler 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT (Guns ‘N Roses), Eddie Trunk, Clem Burke (Blondie) and Eddie Money, along with his daughter Classic Albums Jesse Money, count us down! Black Sabbath: Paranoid - The second album by Black Sabbath, released in 1970, has long at- tained classic status. Paranoid not only changed the face of rock music forever, but also defined 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT the sound and style of Heavy Metal more than any other record in rock history. Plain Spoken: John Mellencamp This stunning, cinematic concert film captures John with his full band, along with special guest 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Carlene Carter, performing his most cherished songs. -

<I>The Axis of Evil Comedy Tour

Global Posts building CUNY Communities since 2009 http://tags.commons.gc.cuny.edu “Persian Like The Cat”: Crossing Borders with The Axis of Evil Comedy Tour Tamara L. Smith/ In the wake of the attacks of September 11, Americans of Middle Eastern heritage experienced a sudden and dramatic change in how their ethnicities were perceived. As comedian and activist Dean Obeidallah explained, “On September 10, I went to bed white, and woke up Arab.”[1] Once comfortable in their American identities, they now had to contend with new cultural forces that configured them as dangerous outsiders. In the months and years that followed, the supposed existence of a so-called “Axis of Evil” of dangerous, anti-American regimes became the justification for expanding military operations abroad, while domestically it fed into a growing Orientalist sentiment that continues to configure Americans of Middle Eastern descent as potentially dangerous outsiders. In 2005, a group of United States comedians of Middle Eastern heritage adopted the alarmist moniker as a tongue-in-cheek title for their stand-up comedy performances. Part commiseration and part public relations, the Axis of Evil Comedy Tour served both as an expression of solidarity between Middle Eastern-Americans and as an act of cultural diplomacy, recasting Middle Eastern ethnic identities as familiar, patriotic, and safe. In this article, I look back to a 2006 performance by the Axis of Evil Comedy Tour in Santa Ana, California, including sets by tour members Ahmed Ahmed, Maz Jobrani, and Aron Kader as well as their guest, New York Arab-American Comedy Festival founder Dean Obeidallah. -

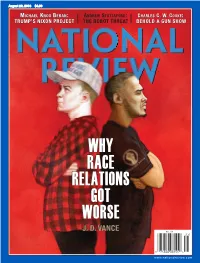

The Democrats Unite Handily

20160829_postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/9/2016 6:40 PM Page 1 August 29, 2016 $4.99 MICHAELICHAEL KNOX BERAN:: ANDREW STUTTAFORD: CHARLES C. W. COOKE:: TRUMP’S NIXON PROJECT THE ROBOT THREAT BEHOLD A GUN SHOW WHY RACE RELATIONS GOT WORSEJ.J. D.D. VANCE VANCE www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/11/2016 3:41 PM Page 1 NATIONAL REVIEW INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES THE 3rd Annual HONORING SECRETARY GEORGE P. SHULTZ FOR HIS ROLE IN DEFEATING COMMUNISM WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN POLITICAL THOUGHT MICHAEL W. GREBE THE LYNDE AND HARRY BRADLEY FOUNDATION WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN SUPPORTING LIBERTY THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2016 CITY HALL SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA For his entire life, Bill Buckley sought to preserve and buttress the foundations of our free society. To honor his achievement and inspire others, National Review Institute’s Board of Trustees has created the William F. Buckley Jr. Prizes for Leadership in Political Thought and Leadership in Supporting Liberty. We hope you will join us this year in San Francisco to support the National Review mission. For reservations and additional information contact Alexandra Zimmern, National Review Institute, at 212.849.2858 or www.nrinstitute.org/wfbprize www.nrinstitute.org National Review Institute (NRI) is the sister nonprofit educational organization of the National Review magazine. NRI is a qualified 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization. EIN#13-3649537 TOC-new_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/10/2016 2:43 PM Page 1 Contents AUGUST 29, 2016 | VOLUME LXVIII, NO. 15 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 23 Stephen D.