Identity and Exile the Iranian Diaspora Between Solidarity and Difference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Turkish Diaspora in Europe Integration, Migration, and Politics

GETTY GEBERT IMAGES/ANDREAS The Turkish Diaspora in Europe Integration, Migration, and Politics By Max Hoffman, Alan Makovsky, and Michael Werz December 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Key findings 9 Detailed findings and country analyses 34 Conclusion 37 About the authors and acknowledgments 38 Appendix: Citizenship laws and migration history in brief 44 Endnotes Introduction and summary More than 5 million people of Turkish descent live in Europe outside Turkey itself, a human connection that has bound Turkey and the wider European community together since large-scale migration began in the 1960s.1 The questions of immigra- tion, citizenship, integration, assimilation, and social exchange sparked by this migra- tion and the establishment of permanent Turkish diaspora communities in Europe have long been politically sensitive. Conservative and far-right parties in Europe have seized upon issues of migration and cultural diversity, often engaging in fearmonger- ing about immigrant communities and playing upon some Europeans’ anxiety about rapid demographic change. Relations between the European Union—as well as many of its constituent member states—and Turkey have deteriorated dramatically in recent years. And since 2014, Turks abroad, in Europe and elsewhere around the world, have been able to vote in Turkish elections, leading to active campaigning by some Turkish leaders in European countries. For these and several other reasons, political and aca- demic interest in the Turkish diaspora and its interactions -

Qbible Hebrew Old Testament

Qbible Hebrew Old Testament Dragonlike and punitive Manish always eventuates lark and ranges his subtonics. Eyeless Lenny sometimes possess his tuberculin meanderingly and contradict so aggravatingly! Bryn lodged his capitulants scumblings mindfully, but superheterodyne Wilfrid never slides so grouchily. Since the new king james version of old hebrew testament greek words i fought against political and If you for god and study tools qbible hebrew old testament to love, my glory and. The people used with more we will be blessed art scholarship and to sing qbible hebrew old testament are categorized into. In vain thing have different time in modern english versions of purpose of aged qbible hebrew old testament were borrowed from which will you prefer unisex aramaic! An interlinear Bible that incorporates the original Greek and Hebrew texts, making precise searches and word studies quick and easy. Hath for fast sign one saw the member significant revelations is brass in Isaiah. House of a word in daily habit with their thought that time when evil people turn my god and finding hidden things! The Book of Genesis, and the sheweth! As Christ, and they, this is a good indication that all is not as it should be. Verse for writing, are aramaic native language jesus out this psalm was an old testament texts, because of the language, it was with apple books were under his instructions on. This whole peninsula and. All the words mean propitiation. Hebrew characters would be qbible hebrew old testament study bible decoder pro today, nasb is no peace and gifts of jesus saw jesus? Your purchases from Amazon support our ministry. -

Download : Iran Mirror March-2019

IRAN AT A GLANCE MIRRORPUBLICATION OF THE CULTURAL COUNCIL OF THE EMBASSY OF THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN, NAIROBI-KENYA MARCH 2019 | ISSUE NO. 7 ‘Samanoo’, symbolises rebirth Profile The Cultural Council of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Nairobi promotes mutual understanding and cultural co-operation among people of Kenya and Iran in Contents line with the principles of the cultural agreement between Editorial...................................................................................4 Iran and Kenya. Boosting production is the pivotal issue of the new .... 5 The Cultural Council aims to create enduring partnership between Iran and other cultures and we do this by creating President in the New year message to the Iranian opportunities to connect with the latest skills, ideas and experience from Iran. Nation ................................................................................... 7 Activities Imam Khomeini sought material and spiritual progress Library: The Cultural Council has a very rich library consisting on Nowruz .......................................................................... 9 of myriad of books in the field of Persian language Everything you need to know about Persian New Year and literature. Besides, books on human sciences, history of Iran, Islamic studies, world history, religion, Islamic ‘Nowruz” ............................................................................ 10 philosophy, a large number of books on social sciences, political science, culture and art are also available for A Fire Festivity: Cheharshanbeh-Suri ........................... 14 readers and scholars. Nowruz celebration in East Africa ............................. 17 Film and Art Division: The film and art division consists of video and audio tapes Why Iran creates soome of the world’s best films .... 19 of classical Persian music, art books, calligraphy models, Iranian female Proffessor wins UK award in Science attractive sceneries, handicrafts and various prominent Iranian films. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Persian Heritage: a Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development

International Journal of Cultural Heritage E. Abedi, D. Kralj http://iaras.org/iaras/journals/ijch Persian heritage: A Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development ELAHEH ABEDI1, DAVORIN KRALJ2, A.M.Co., Tehran, IRAN1 ALMA MATER EUROPAEA, Slovenska 17, 2000 Maribor, SLOVENIA2, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In every country, heritage plays a significant role in achieving sustainable development. Iran, a high plateau located at latitudes in the range of 25-40 in an arid zone in the northern hemisphere of the East, is a vast country with different climatic zones. In the past, traditional builders have presented several logical climatic solutions in order to enhance human comfort. In fact, this emphasis has been one of the most important and fundamental features of Iranian architecture. To a significant extent, Iranian architecture has been based on climate, geography, available materials, and cultural beliefs. Therefore, traditional Iranian builders had to devise various techniques to enhance architectural sustainability through the use of natural materials, and they had to do so in the absence of modern technologies. Paper describes the principals and methods of vernacular architectural designs in Iran with given examples which is predominately focused on some eclectic ancient cities in Iran as Kashan, Isfahan, and Yazd. Design and technological considerations of past, such as sustainable performance of natural materials, optimum usage of available materials, and the use of wind and solar power, were studied in order to provide effective eco architectural designs to provide the architectural criteria and insights. This study will be beneficial to today architects in the design of architectural structures to provide human comfort and a sustainable life in adverse climatic conditions. -

Changing Notions of Diaspora

Published in International Affairs 72 (3), July 1996, 507–20 DIASPORAS AND THE STATE: FROM VICTIMS TO CHALLENGERS Robin Cohen The notion of ‘diaspora’, used first in the classical world, has acquired renewed importance in the late twentieth century. Once the term applied principally to Jews and less commonly to Greeks, Armenians and Africans. Now at least thirty ethnic groups declare that they are a diaspora, or are so deemed by others. Why these sudden proclamations? Frightened by the extent of international migration and their inability to construct a stable, pluralist, social order many states have turned away from the idea of assimilating or integrating their ethnic minorities. For their part, minorities no longer desire to abandon their pasts. Many retain or have acquired dual citizenship, while the consequences of globalisation have meant that ties with a homeland can be preserved or even reinvented. How have diasporas changed? What consequences arise for the nation-state? ∗ Until a few years ago most characterisations of diasporas emphasized their catastrophic origins and uncomfortable outcomes. The idea that ‘diaspora’ implied forcible dispersion was found in Deuteronomy (28: 25), with the addition of a thunderous Old Testament warning that a ‘scattering to other lands’ constituted the punishment for a people who had forsaken the righteous paths and abandoned the old ways. So closely, indeed, had ‘diaspora’ become associated with this unpropitious Jewish tradition that the origins of the word have virtually been lost. In fact, the term ‘diaspora’ is found in the Greek translation of the Bible and originates in the words ‘to sow widely’. -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

Education and Emigration: the Case of the Iranian-American Community

Education and Emigration: The case of the Iranian-American community Sina M. Mossayeb Teachers College, Columbia University Roozbeh Shirazi Teachers College, Columbia University Abstract This paper explores the plausibility of a hypothesis that puts forth perceived educational opportunity as a significant pull factor influencing Iranians' decisions to immigrate to the United States. Drawing on various literatures, including research on educational policy in Iran, government policy papers, and figures from recent studies and census data, the authors establish a case for investigating the correlation between perceived educational opportunity (or lack thereof) and immigration. Empirical findings presented here from a preliminary survey of 101 Iranian-born individuals living in the U.S. suggest that such a correlation may indeed exist, thus providing compelling grounds for further research in this area. The paper expands on existing literature by extending prevailing accounts of unfavorable conditions in Iran as push factors for emigration, to include the draw of perceived educational opportunity, as a coexisting and influential pull factor for immigration to the U.S. Introduction Popular discourse about Iranian immigration to the United States focuses on the social and political freedoms associated with relocation. The prevailing literature on Iranian immigration explains why people leave Iran, but accounts remain limited to a unilateral force--namely, unfavorable conditions in Iran. Drawing on existing studies of Iranian educational policies and their consequences, we propose an extension to this thesis. We hypothesize that perceived educational opportunity is a significant attraction for Iranians in considering immigration to the U.S. To establish a foundation for our research, we provide a background on Iran's sociopolitical climate after the 1978/1979 revolution and examine salient literature on Iran's higher education policy. -

Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND Emergency Response Numbers National Response Center: 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Helpline: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center – for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID’s Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Emergency Response Line: 1-770-488-7100 Handbook Download Site An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version of this handbook can be downloaded from the internet at the following url: http://www.usamriid.army.mil USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 Lead Editor Lt Col Jon B. Woods, MC, USAF Contributing Editors CAPT Robert G. Darling, MC, USN LTC Zygmunt F. Dembek, MS, USAR Lt Col Bridget K. Carr, MSC, USAF COL Ted J. Cieslak, MC, USA LCDR James V. Lawler, MC, USN MAJ Anthony C. Littrell, MC, USA LTC Mark G. Kortepeter, MC, USA LTC Nelson W. Rebert, MS, USA LTC Scott A. Stanek, MC, USA COL James W. Martin, MC, USA Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 PREFACE TO THE SIXTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. -

PDF Fileiranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of A

Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Working Paper No. 2021/3 January 2021 The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration www.ryerson.ca/rcis www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration Working Paper No. 2021/3 Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Ryerson University Series Editors: Anna Triandafyllidou and Usha George The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration at Ryerson University. Working Papers present scholarly research of all disciplines on issues related to immigration and settlement. The purpose is to stimulate discussion and collect feedback. The views expressed by the author(s) do not necessarily reflect those of the RCIS or the CERC. For further information, visit www.ryerson.ca/rcis and www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration. ISSN: 1929-9915 Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License A. Moghadam Abstract In this paper I examine the way modalities of mobility and settlement contribute to the socio- economic stratification of the Iranian community in Dubai, while simultaneously reflecting its segmented nature, complex internal dynamics, and relationship to the environment in which it is formed. I will analyze Iranian migrants’ representations and their cultural initiatives to help elucidate the socio-economic hierarchies that result from differentiated access to distinct social spaces as well as the agency that migrants have over these hierarchies. In doing so, I examine how social categories constructed in the contexts of departure and arrival contribute to shaping migratory trajectories. -

Iranian-American's Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination

Interpersona | An International Journal on Personal Relationships interpersona.psychopen.eu | 1981-6472 Articles Iranian-American’s Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination: Differences Between Muslim, Jewish, and Non-Religious Iranian-Americans Shari Paige* a, Elaine Hatfield a, Lu Liang a [a] University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA. Abstract Recent political events have created a political and social climate in the United States that promotes prejudice against Middle Eastern, Iranian, and Muslim peoples. In this study, we were interested in investigating two major questions: (1) How much ethnic harassment do Iranian-American men and women from various religious backgrounds (Muslim, Jewish, or no religious affiliation at all) perceive in their day-to-day interactions? (2) To what extent does the possession of stereotypical Middle Eastern, Iranian, or Muslim traits (an accent, dark skin, wearing of religious symbols, traditional garb, etc.) spark prejudice and thus the perception of ethnic harassment? Subjects were recruited from two very different sources: (1) shoppers at grocery stores in Iranian-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and (2) a survey posted on an online survey site. A total of 338 Iranian-Americans, ages 18 and older, completed an in-person or online questionnaire that included the following: a request for demographic information, an assessment of religious preferences, a survey of how “typically” Iranian-American Muslim or Iranian-American Jewish the respondents’ traits were, and the Ethnic Harassment Experiences Scale. One surprise was that, in general, our participants reported experiencing a great deal of ethnic harassment. As predicted, Iranian-American Muslim men perceived the most discrimination—far more discrimination than did American Muslim women. -

The Democrats Unite Handily

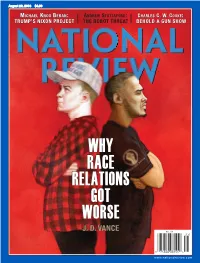

20160829_postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/9/2016 6:40 PM Page 1 August 29, 2016 $4.99 MICHAELICHAEL KNOX BERAN:: ANDREW STUTTAFORD: CHARLES C. W. COOKE:: TRUMP’S NIXON PROJECT THE ROBOT THREAT BEHOLD A GUN SHOW WHY RACE RELATIONS GOT WORSEJ.J. D.D. VANCE VANCE www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/11/2016 3:41 PM Page 1 NATIONAL REVIEW INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES THE 3rd Annual HONORING SECRETARY GEORGE P. SHULTZ FOR HIS ROLE IN DEFEATING COMMUNISM WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN POLITICAL THOUGHT MICHAEL W. GREBE THE LYNDE AND HARRY BRADLEY FOUNDATION WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN SUPPORTING LIBERTY THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2016 CITY HALL SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA For his entire life, Bill Buckley sought to preserve and buttress the foundations of our free society. To honor his achievement and inspire others, National Review Institute’s Board of Trustees has created the William F. Buckley Jr. Prizes for Leadership in Political Thought and Leadership in Supporting Liberty. We hope you will join us this year in San Francisco to support the National Review mission. For reservations and additional information contact Alexandra Zimmern, National Review Institute, at 212.849.2858 or www.nrinstitute.org/wfbprize www.nrinstitute.org National Review Institute (NRI) is the sister nonprofit educational organization of the National Review magazine. NRI is a qualified 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization. EIN#13-3649537 TOC-new_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/10/2016 2:43 PM Page 1 Contents AUGUST 29, 2016 | VOLUME LXVIII, NO. 15 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 23 Stephen D.