Firearm Possession and Use Among Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Weird Nukes of Yesteryear

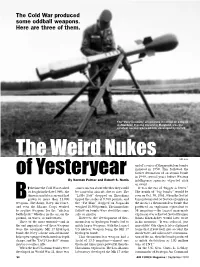

The Cold War produced some oddball weapons. Here are three of them. The “Davy Crockett,” shown here mounted on a tripod at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, was the smallest nuclear warhead ever developed by the US. The Weird Nukes DOD photo end of a series of thermonuclear bombs initiated in 1950. This followed the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb of Yesteryear in 1949, several years before Western By Norman Polmar and Robert S. Norris intelligence agencies expected such an event. y the time the Cold War reached some concern about whether they could It was the era of “bigger is better.” its height in the late 1960s, the be carried in aircraft, due to size. The The zenith of “big bombs” would be American nuclear arsenal had “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima seen on Oct. 30, 1961, when the Soviet grown to more than 31,000 tipped the scales at 9,700 pounds, and Union detonated (at Novaya Zemlya in Bweapons. The Army, Navy, Air Force, the “Fat Man” dropped on Nagasaki the Arctic) a thermonuclear bomb that and even the Marine Corps worked weighed 10,300 pounds. The immediate produced an explosion equivalent to to acquire weapons for the “nuclear follow-on bombs were about the same 58 megatons—the largest man-made battlefield,” whether in the air, on the size or smaller. explosion ever achieved. Soviet Premier ground, on water, or underwater. However, the development of ther- Nikita Khrushchev would later write Three of the more unusual—and in monuclear or hydrogen bombs led to in his memoirs: “It was colossal, just the end impractical—of these weapons much larger weapons, with the largest incredible! Our experts later explained were the enormous Mk 17 hydrogen US nuclear weapon being the Mk 17 to me that if you took into account the bomb, the Navy’s drone anti-submarine hydrogen bomb. -

Hunting the Collectors Pacific Collections in Australian Museums, Art Galleries and Archives

Hunting the Collectors Pacific Collections in Australian Museums, Art Galleries and Archives Edited by SUSAN COCHRANE and MAX QUANCHI Cambridge Scholars Publishing HUNTING THE COLLECTORS Hunting the Collectors: Pacific Collections in Australian Museums, Art Galleries and Archives Edited by Susan Cochrane and Max Quanchi This book first published 2007 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK Second edition published 2010 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright ©2007 by Susan Cochrane and Max Quanchi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-084-1, ISBN (13): 9781847180841 Chapter 3 The perils of ethnographic provenance: the documentation of the Johnson Fiji Collection in the South Australian Museum RODERICK EWINS 3 HUNTING THE COLLECTORS The perils of ethnographic provenance: the documentation of the Johnson Fiji Collection in the South Australian Museum RODERICK EWINS This essay addresses the vexed questions of provenance and authenticity of objects that have been collected and made accessible for study. It calls for an exploration of the way in which these have often been uncritically accepted solely on the basis of notes and comments made by the original collectors. The difficulty is that the authority with which collectors were able to speak varied enormously, and even when the collectors obtained objects personally from the original owners, it cannot be assumed that they understood clearly the names, purposes or provenance of the objects they obtained. -

I PRESENT ARMS: DISPLAYING WEAPONS in MUSEUMS a Thesis

PRESENT ARMS: DISPLAYING WEAPONS IN MUSEUMS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY by Derek Engle May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Dr. Seth Bruggeman, Thesis Advisor, Department of History Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin, Department of History i ABSTRACT Museums have always had and displayed weapons, including firearms. As museums have evolved, so too has exhibit design and practice. However, many weapons displays have not kept up with changing practices, and many of them are now irrelevant, have limited audiences, or are unhelpful to the broader public. Simply displaying weapons by type or as art is not enough anymore, and keeping them in storage does not take advantage of their potential. Also, many museums are increasingly trying to become places for public discourse about current issues. They often create exhibits meant to be relevant to today and promote discussions about controversial topics. Many museums are also trying to make their collections and objects more accessible to the public. Innovative displays of firearms could help them accomplish both these tasks. The battle over gun control and gun rights is often more of a shouting match than reasoned discourse. Museums could use historic firearms as an opportunity to help facilitate a more responsible conversation about the issue. These firearms are typically not as emotionally charged as modern guns, and could be used as a pathway into the gun debate if displayed creatively. Guns, historic or not, are often not very approachable objects for many people. This can be for a variety of reasons, including their associations with masculinity, power, and nationality. -

New Technologies and Warfare

New technologies and warfare Volume 94 Number 886 Summer 2012 94 Number 886 Summer 2012 Volume Volume 94 Number 886 Summer 2012 Editorial: Science cannot be placed above its consequences Interview with Peter W. Singer New capabilities in warfare: an overview [...] Alan Backstrom and Ian Henderson Cyber conflict and international humanitarian law Herbert Lin Get off my cloud: cyber warfare, international humanitarian law, and the protection of civilians Cordula Droege Some legal challenges posed by remote attack William Boothby Pandora’s box? Drone strikes under jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and international human rights law Stuart Casey-Maslen Categorization and legality of autonomous and remote weapons systems and warfare technologies New Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action Hin-Yan Liu Nanotechnology and challenges to international humanitarian law: a preliminary legal assessment Hitoshi Nasu Conflict without casualties … a note of caution: non-lethal weapons and international humanitarian law Eve Massingham On banning autonomous weapon systems: human rights, automation, and the dehumanization of lethal decision-making Peter Asaro Beyond the Call of Duty: why shouldn’t video game players face the same dilemmas as real soldiers? Ben Clarke, Christian Rouffaer and François Sénéchaud Documenting violations of international humanitarian law from [...] Joshua Lyons The roles of civil society in the development of standards around new weapons and other technologies of warfare Brian Rappert, Richard Moyes, Anna Crowe and Thomas Nash The -

A Historical Argument for a Cluster Munitions Convention

The Time Is Now: A Historical Argument for a Cluster Munitions Convention Bonnie Docherty* I. INTRODUCTION While traveling through Italy in June 1859, Swiss businessman Henri Dunant happened upon the aftermath of the Battle of Solferino. He found "despair unspeakable and misery of every kind."' Mangled bodies, dead and alive, littered the field, and the cries of the wounded filled the air. "The poor wounded men . were ghastly pale and exhausted," he wrote, describing the scene: Some, who had been the most badly hurt, had a stupefied look as though they could not grasp what was said to them .... Others were anxious and excited by nervous strain and shaken by spas- modic trembling. Some, who had gaping wounds already begin- 2 ning to show infection, were almost crazed with suffering. Dunant's recollections, A Memory of Solferino (1862), became a catalyst for the first modern instrument of international humanitarian law CIHL"), the 1864 Geneva Convention.' This treaty provided protection for the wounded on the battlefield, and it also showed that nations had the legal power to ameliorate suffering in war. The first Geneva Convention in turn spawned a branch of IHL that seeks to minimize war's effects by controlling the weap- ons used. Since the late nineteenth century, the international community has regu- lated or banned weapons it found caused undue harm to soldiers or civil- ians. Some of these treaties are out of date. For example, an 1899 Hague Declaration prohibiting bombs dropped from balloons seems archaic in the * Clinical Instructor, Human Rights Program, Harvard Law School; researcher, Arms Division, Human Rights Watch. -

Ls Denver Museum of Nature & Science Annals

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE & SCIENCE OF NATURE DENVER MUSEUM DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE ANNALS DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE ANNALS NUMBER 7, OCTOBER 11, 2018 WWW.DMNS.ORG/SCIENCE/MUSEUM-PUBLICATIONS Denver Museum of Nature & Science Annals (Print) ISSN 1948-9293 2001 Colorado Boulevard Denver, CO 80205, U.S.A. Denver Museum of Nature & Science Annals (Online) ISSN 1948-9307 ANNALS • NUMBER 7 • OCTOBER 11, 2018 • NUMBER 7 OCTOBER The Denver Museum of Nature & Science inspires curiosity and excites minds of all ages through scientific discovery and the presentation and preservation of the world’s unique treasures. Cover photo: Model Paopao (single-hull outrigger canoe) collected in Sāmoa before 1977 (DMNS A967.6). Model canoes are found all throughout the seafaring cultures of Oceania and within the walls of museums. Their presence in collections across the world continue to evince the relationship of Pacific Islanders to the sea and to each other. The Denver Museum of Nature & Science Annals is an Frank Krell, PhD, Editor-in-Chief Voyaging through the Oceanic Collection open-access, peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing EDITORIAL BOARD: original papers in the fields of anthropology, geology, at the Denver Museum of Nature & James Hagadorn, PhD (subject editor, Paleontology and paleontology, botany, zoology, space and planetary Science Geology) sciences, and health sciences. Papers are either authored Nicole Garneau, PhD (subject editor, Health Sciences) by DMNS staff, associates, or volunteers, deal with DMNS John Demboski, PhD (subject editor, Vertebrate Zoology) specimens or holdings, or have a regional focus on the Steve Lee, PhD (subject editor, Space Sciences) Rocky Mountains/Great Plains ecoregions. -

Avoiding an Arms Race in Outer Space

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2018 The Fault Is Not in Our Stars: Avoiding an Arms Race in Outer Space David A. Koplow Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2083 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3058132 David A. Koplow, The Fault Is Not in Our Stars: Avoiding an Arms Race in Outer Space, 59 Harv. Int'l L.J. 331 (2018) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Air and Space Law Commons \\jciprod01\productn\H\HLI\59-2\HLI205.txt unknown Seq: 1 21-JUN-18 12:17 Volume 59, Number 2, Summer 2018 The Fault Is Not in Our Stars: Avoiding an Arms Race in Outer Space David A. Koplow* Men at some time are masters of their fates; The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves, that we are underlings. —William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, act 1, sc. 2 The world is on the precipice of a new arms race in outer space, as China, Russia, the United States, and others undertake dramatic new initiatives in anti-satellite weaponry. These accelerated competitive efforts at space control are highly destabilizing because developed societies have come to depend so heavily upon satellite services to support the entire civilian economy and the modern military apparatus; any significant threat or disruption in the availability of space assets would be massively, and possibly perma- nently, disruptive. -

The Historical Evolution of Arms and Armor: the European Arming Sword and Japanese Uchigatana

The Historical Evolution of Arms and Armor: The European Arming Sword and Japanese Uchigatana An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science By Brendan Corcoran Christopher Francis Colby Jensen Kevin Piskorowski David Van Sickle Date: May 13, 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on the web without editorial or peer review. ABSTRACT The late medieval period of Europe (1250-1500 AD) and the Kamakura Period of Japan (1185- 1333 AD) were both eras defined by perpetual conflict and warfare. As a result, a rich history of weapons and armor was developed. The sword was one such weapon that saw widespread use in combat. This project seeks to investigate two specific swords, the European arming sword and the Japanese uchigatana. The factors that led to these swords’ demand and forging processes used to create them will be revealed with a thorough exploration of the historical context. Additionally, replicas of both an arming sword and uchigatana will be fabricated in a historically representative manner. An analysis of the design, forging process, and materials science aspects will be considered to compare these two swords, originating from two vastly different regions of the world in a similar time of unrest. 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The team would like to first thank Professor Diana Lados for involving us with this multifaceted and in-depth learning experience. -

Proliferation of Biological Weapons Into Terrorist Hands

PROLIFERATION OF BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS INTO TERRORIST HANDS BY RICHARD DANZIG1 NUNN PRIZE FELLOW,CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES u Because of their relative ease of purchase and development, biological weapons have been called “the poor man’s nuclear bomb.” This paper examines the extent to which such weapons are likely to spread – in particular, to terrorist hands – and whether the United States and its allies effective- ly control their proliferation. It concludes that while we can and should take useful steps, biolog- ical weapons will proliferate and we will be unable to retard this proliferation as effectively as we retarded nuclear proliferation over the past 60 years. BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS:WHY AND HOW Discussion of biological weapons is complicated by their diversity and their unfamiliarity. It helps, therefore, to focus on five “reference cases”:2 (1) use of anthrax (a bacterium) in a major outdoor aerosol attack; (2) use of smallpox (a virus) in an indoor aerosol attack (for example, through a building heat- ing, ventilation, and air conditioning [HVAC] system); (3) dissemination of a toxin,3 such as botulinum, through the food supply, for example through cold drinks; (4) spread of foot and mouth disease (a virus that does not affect humans) in cows, pigs, and sheep; (5) the invention and dispersal of a pathogen that does not have the attributes of pathogens that exist in nature. All biological agents that appear on U.S. agency threat lists now exist (or in the case of smallpox, used to exist) in nature. This last case – sometimes now called “Case 5” or “Case X”4– is less pressing, but obviously more open-ended and therefore most complex. -

Nanotechnology and the Future of the Law of Weaponry

Nanotechnology and the Future of the Law of Weaponry Hitoshi Nasu 91 INT’L L. STUD. 486 (2015) Volume 91 2015 Published by the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law International Law Studies 2015 Nanotechnology and the Future of the Law of Weaponry Hitoshi Nasu* CONTENTS I. Introduction .............................................................................................. 487 II. Nanotechnology and the Law of Weaponry......................................... 491 III. Weapons Law Paradox ............................................................................ 498 IV. The Potential of Nanotechnology to Bring Change to the Law of Weaponry ................................................................................................... 503 A. The Power to Kill or Capture Debate ............................................ 504 B. The Legality of Incapacitating Chemical Agents Debate ............. 509 V. Conclusion ................................................................................................. 514 * Senior Lecturer in Law, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. The foundational research on military applications of nanotechnology and legal implica- tions was supported by the Australian Research Council under its Discovery Grant fund- ing scheme (Project ID: DP110102637) and was presented at the Workshop on Legal Im- plications of Future Weapons Technology, jointly hosted by the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College and the International Commit- tee of the Red Cross, Newport, Rhode Island, February 24–25, 2015. I thank the partici- pants of the Workshop for the informative discussion and Dr. William H. Boothby and Associate Professor Rob McLaughlin for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. All errors remain mine. The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the author and not necessarily of the U.S. government, the U.S. Department of the Navy or the U.S. Naval War College. 486 Nanotechnology and the Future of the Law of Weaponry Vol. -

PDF Download Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe

WEAPONS AND WARFARE IN RENAISSANCE EUROPE: GUNPOWDER, TECHNOLOGY, AND TACTICS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bert S. Hall | 320 pages | 18 Dec 2001 | JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780801869945 | English | Baltimore, MD, United States Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics PDF Book The mangonel was not very accurate and hurled the projectiles at a much lower angle than the trebuchet. Seller Inventory U. There are many types of siege engines. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves. Add to Basket Used Softcover. The stakes used at agincourt were an early version of the field fortifications later built to protect arquebusiers. Battle of Ceresole. David Kush rated it really liked it Dec 19, James rated it it was amazing Dec 09, Other Editions 1. About this Item: Hardcover. Artillery weapons until the advent of the cannon into Europe were a series of lever and pulley designs such as the trebuchet of the Medieval Age used for siege warfare. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. The soldier was expected to either bring their own gun, or be loaned one from the military. The other advantage that a bow possessed was the ability to shoot a projectile in rapid succession. Jonathan rated it it was amazing Aug 12, Another example of guns being effectively used on the battlefield was in the Battle of Beverhoudsveld on May 3rd, You must log in to edit Common Knowledge data. Google Books — Loading Black points out the battle of Hormuz of Those few issues aside, the book covered exactly what I was hoping for, and left me interested in finding out more about the role and development of firearms in other regions and eras. -

Embodiments of Power and Prestige Power of Embodiments

EMBODIMENTS OF POWER AND PRESTIGE EXCEPTIONAL TRIBAL ARMS, ARMOR AND TEXTILES FROM A PRIVATE EUROPEAN COLLECTION Tuesday May 22, 2018 Los Angeles EMBODIMENTS OF POWER AND PRESTIGE | Los Angeles | Tuesday May 22, 2018 | Los Angeles Tuesday 24946 EMBODIMENTS OF POWER AND PRESTIGE EXCEPTIONAL TRIBAL ARMS, ARMOR AND TEXTILES FROM A PRIVATE EUROPEAN COLLECTION Tuesday May 22, 2018 at 1pm Los Angeles BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 7601 West Sunset Blvd, +1 (323) 850 7500 Fredric Backlar Monday – Friday 9am-5pm Los Angeles, California 90046 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Consulting Specialist +1 (323) 850 7500 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (323) 436-5416 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit ILLUSTRATIONS Saturday, May 19 www.bonhams.com/24946 Cassandra D’Cruz Front cover: Lot 32 12-8pm Business Administrator Back cover: Lot 79 Sunday, May 20 Please note that telephone bids +1 (323) 436-5434 12-5pm must be submitted no later than [email protected] Monday, May 21 4pm on the day prior to the 10-5pm auction. New bidders must also Automated Results Service Tuesday, May 22 provide proof of identity and +1 (800) 223 2854 10-1pm address when submitting bids. Please contact client services SALE NUMBER: with any bidding inquiries. 24946 Lots 1-94 Please see pages 108 to 110 for bidder information including CATALOG: $35 Conditions of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Bonhams 220 San Bruno Avenue San Francisco, California 94103 © 2018, Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp.; All rights reserved. Bond No.