Proliferation of Biological Weapons Into Terrorist Hands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biotechnology Research in an Age of Terrorism: Confronting the Dual Use Dilemma

Prepublication Copy BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH IN AN AGE OF TERRORISM: CONFRONTING THE DUAL USE DILEMMA Committee on Research Standards and Practices to Prevent the Destructive Application of Biotechnology Development, Security, and Cooperation Policy and Global Affairs National Research Council OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES The National Academies Press Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu Prepublication Copy Uncorrected Proofs THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES 500 FIFTH STREET, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the Committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. Financial Support: The development of this report was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Nuclear Threat Initiative. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or agencies that provided support for the project. International Standard Book Number 0-309-09087-3 Additional copies of this report are available from National Academies Press, 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, D.C. 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, //www.nap.edu Printed in the United States of America Copyright 2003 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Prepublication Copy Uncorrected Proofs The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare. -

Conversions of Former Biological Weapons Facilities in Kazakhstan

SWEDISH DEFENCE RESEARCH AGENCY FOI-R--0082--SE NBC Defence May 2001 SE-901 82 Umeå ISSN 1650-1942 User report Conversion of former biological weapons facilities in Kazakhstan A visit to Stepnogorsk July 2000 Roger Roffey, Kristina S. Westerdahl 2 Issuing organization Report number, ISRN Report type FOI – Swedish Defence Research Agency FOI-R--0082--SE User report NBC Defence Research area code SE-901 82 Umeå 3. Weapons of Mass Destruction Month year Project no. May 2001 A472 Customers code 2. NBC-Defence Research Sub area code 34 Biological and Chemical Defence Research Author/s (editor/s) Project manager Roger Roffey Lars Rejnus Kristina S. Westerdahl Approved by Scientifically and technically responsible Report title Conversion of former biological weapons facilities in Kazakhstan, A visit to Stepnogorsk July 2000 Abstract (not more than 200 words) Report from the conference “Biotechnological development in Kazakhstan: Non-proliferation, conversion and investment” held in Stepnogorsk, Kazakhstan July 24-26 2000. The conference was sponsored by US DOD and organised by the Biotechnology Centre at Stepnogorsk in co-operation with the NIS Representative office in Astana, Kazakhstan of the Centre for Non-proliferation Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies. The conference concentrated on the dismantlement and conversion of former BW producers. The intent was to present to a larger public the results of the US DOD CTR (Cooperative Threat Reduction) program at the Biotechnology Centre of Stepnogorsk and attract some potential partners to encourage conversion projects. The conference gave a good overview of the conversion projects in progress in Kazakhstan and scientific results were presented of research being funded by the US. -

1540 Committee Matrix of Slovakia

1540 COMMITTEE MATRIX OF SLOVAKIA The information in the matrices originates primarily from national reports and is complemented by official government information, including that made available to inter-governmental organizations. The matrices are prepared under the direction of the 1540 Committee. The 1540 Committee intends to use the matrices as a reference tool for facilitating technical assistance and to enable the Committee to continue to enhance its dialogue with States on their implementation of Security Council Resolution 1540. The matrices are not a tool for measuring compliance of States in their non-proliferation obligations but for facilitating the implementation of Security Council Resolutions 1540 (2004), 1673 (2006), 1810 (2008) and 1977 (2011). They do not reflect or prejudice any ongoing discussions outside of the Committee, in the Security Council or any of its organs, of a State's compliance with its non-proliferation or any other obligations. Information on voluntary commitments is for reporting purpose only and does not constitute in any way a legal obligation arising from resolution 1540 or its successive resolutions. OP 1 and related matters from OP 5, OP 6, OP 8 (a), (b), (c) and OP 10 State: SLOVAKIA Date of Report: 2 November 2004 Date of First Addendum: 14 December 2004 Date of Second Addendum: 14 December 2007 Date of Committee Approval: Remarks (information refers Legally binding instruments, to the page of the organizations, codes of YES if YES, relevant information (i.e. signing, accession, ratification, -

![The Australia Group LIST of HUMAN and ANIMAL PATHOGENS and TOXINS for EXPORT CONTROL[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3423/the-australia-group-list-of-human-and-animal-pathogens-and-toxins-for-export-control-1-443423.webp)

The Australia Group LIST of HUMAN and ANIMAL PATHOGENS and TOXINS for EXPORT CONTROL[1]

The Australia Group LIST OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL PATHOGENS AND TOXINS FOR EXPORT CONTROL[1] July 2017 Viruses 1. African horse sickness virus 2. African swine fever virus 3. Andes virus 4. Avian influenza virus[2] 5. Bluetongue virus 6. Chapare virus 7. Chikungunya virus 8. Choclo virus 9. Classical swine fever virus (Hog cholera virus) 10. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus 11. Dobrava-Belgrade virus 12. Eastern equine encephalitis virus 13. Ebolavirus: all members of the Ebolavirus genus 14. Foot-and-mouth disease virus 15. Goatpox virus 16. Guanarito virus 17. Hantaan virus 18. Hendra virus (Equine morbillivirus) 19. Japanese encephalitis virus 20. Junin virus 21. Kyasanur Forest disease virus 22. Laguna Negra virus 23. Lassa virus 24. Louping ill virus 25. Lujo virus 26. Lumpy skin disease virus 27. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus 28. Machupo virus 29. Marburgvirus: all members of the Marburgvirus genus 30. Monkeypox virus 31. Murray Valley encephalitis virus 32. Newcastle disease virus 33. Nipah virus 34. Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus 35. Oropouche virus 36. Peste-des-petits-ruminants virus 37. Porcine Teschovirus 38. Powassan virus 39. Rabies virus and other members of the Lyssavirus genus 40. Reconstructed 1918 influenza virus 41. Rift Valley fever virus 42. Rinderpest virus 43. Rocio virus 44. Sabia virus 45. Seoul virus 46. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-related coronavirus) 47. Sheeppox virus 48. Sin Nombre virus 49. St. Louis encephalitis virus 50. Suid herpesvirus 1 (Pseudorabies virus; Aujeszky's disease) 51. Swine vesicular disease virus 52. Tick-borne encephalitis virus (Far Eastern subtype) 53. Variola virus 54. -

Alibek, Tularaemia and the Battle of Stalingrad

Obligations (EC-36/DG.16 dated 4 March 2004, Corr.1 dated 15 Conference of the States Parties (C-9/6, dated 2 December 2004). March 2004 and Add.1 dated 25 March 2004); Information on 13 the Implementation of the Plan of Action for the Implementation Conference decision C-9/DEC.4 dated 30 November 2004, of Article VII Obligations (S/433/2004 dated 25 June 2004); Second www.opcw.org. Progress Report on the OPCW Plan of Action Regarding the 14 Note by the Director-General: Report on the Plan of Action Implementation of Article VII Obligations (EC-38/DG.16 dated Regarding the Implementation of Article VII Obligations (EC- 15 September 2004; Corr.1 dated 24 September 2004; and Corr.2 42/DG.8 C-10/DG.4 and Corr.1 respectively dated 7 and 26 dated 13 October 2004); Report on the OPCW Plan of Action September 2005; EC-M-25/DG.1 C-10/DG.4/Rev.1, Add.1 and Regarding the Implementation of Article VII Obligations (C-9/ Corr.1, respectively dated 2, 8 and 10 November 2005). DG.7 dated 23 November 2004); Third Progress Report on the 15 OPCW Plan of Action Regarding the Implementation of Article One-hundred and fifty-six drafts have been submitted by 93 VII Obligations (EC-40/DG.11 dated 16 February 2005; Corr.1 States Parties. In some cases, States Parties have requested dated 21 April 2005; Add.1 dated 11 March 2005; and Add.1/ advice on drafts several times during their governmental Corr.1 dated 14 March 2005); Further Update on the Plan of consultative process. -

Toxic Archipelago: Preventing Proliferation from the Former Soviet Chemical and Biological Weapons Complexes

Toxic Archipelago: Preventing Proliferation from the Former Soviet Chemical and Biological Weapons Complexes Amy E. Smithson Report No. 32 December 1999 Copyright©1999 11 Dupont Circle, NW Ninth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 [email protected] Copyright©1999 by The Henry L. Stimson Center 11 Dupont Circle, NW Ninth Floor Washington, DC 20036 tel 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 email [email protected] Preface and Acknowledgments This report is the second major narrative by the Stimson Center’s Chemical and Biological Weapons Nonproliferation Project on the problems associated with the vast chemical and biological weapons capabilities created by the USSR. An earlier report, Chemical Weapons Disarmament in Russia: Problems and Prospects (October 1995), contained the first public discussion of security shortcomings at Russia’s chemical weapons facilities and the most detailed account publicly available of the top secret chemical weapons development program of Soviet origin, code-named novichok. Toxic Archipelago examines another aspect of the USSR’s weapons of mass destruction legacy, the proliferation problems that stem from the former Soviet chemical and biological weapons complexes. Given the number of institutes and individuals with expertise in chemical and biological weaponry that have been virtually without the financial support of their domestic governments since the beginning of 1992, this report provides an overview of a significant and complex proliferation dilemma and appraises the efforts being made to address it. This topic and other issues of chemical and biological weapons proliferation concern are also covered on the project’s worldwide web page, which can be found at the Chemical and Biological Weapons Nonproliferation Project section of the Stimson web site at: www.stimson.org/. -

Responding to the Threat of Agroterrorism: Specific Recommendations for the United States Department of Agriculture

Responding to the Threat of Agroterrorism: Specific Recommendations for the United States Department of Agriculture Anne Kohnen ESDP-2000-04 BCSIA-2000-29 October 2000 CITATION AND REPRODUCTION This document appears as Discussion Paper 2000-29 of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and as contribution ESDP-2000-04 of the Executive Session on Domestic Preparedness, a joint project of the Belfer Center and the Taubman Center for State and Local Government. Comments are welcome and may be directed to the author in care of the Executive Session on Domestic Session. This paper may be cited as Anne Kohnen. “Responding to the Threat of Agroterrorism: Specific Recommendations for the United States Department of Agriculture.” BCSIA Discussion Paper 2000-29, ESDP Discussion Paper ESDP-2000-04, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, October 2000. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Anne Kohnen graduated from the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, in June 2000, with a Master’s degree in public policy, specializing in science and technology policy. This paper is an extension of her Master’s thesis. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author expresses special thanks go to the following people who contributed to this paper valuable information and expertise. From the USDA: Jerry Alanko, Dr. Bruce Carter, Dr. Tom Gomez, Dr. David Huxsoll, Dr. Steve Knight, Dr. Paul Kohnen, Dr. Marc Mattix, Dr. Norm Steele, Dr. Ian Stewart, Dr. Ty Vannieuwenhoven, Dr. Tom Walton, and Dr. Oliver Williams. From other agencies: Dr. Norm Schaad (USAMRIID), Dr. Tracee Treadwell (CDC). From the Kennedy School of Government: Dr. Richard Falkenrath, Greg Koblentz, Robyn Pangi, and Wendy Volkland. -

Chapter 4 Considering US Proposals for Enhanced Biosafety, Biosecurity, and Research Oversight

Chapter 4 Considering US Proposals for Enhanced Biosafety, Biosecurity, and Research Oversight f the proposals that the US government tabled to stand in for a monitoring protocol for the OBiological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC), the industry experts reacted most positively to those calling for BWC members to improve standards for biosafety, biosecurity, and oversight of genetic engineering research. They tempered their praise with criticism of the state-by-state structure of the proposals, which they saw as undercutting their potential efficacy. The industry group recommended instead that the United States advocate international adoption of common minimum standards in each of the areas, based on current US regulations and guidelines, or their equivalent. Taking the US government’s biosafety, biosecurity, and research oversight initiatives in turn, this chapter reviews the industry group’s discussion of pertinent domestic efforts. The industry experts then explain why some changes are needed domestically and how to achieve them. Improvements at home will pave the way for the successful promotion of similar initiatives internationally. As one participant noted, “If we don't walk before we run, if we don't set up things at home first to serve as an international model, I'm not going to count on anyone else to do it.”1 In each topical area, the industry group makes specific recommendations to strengthen the US proposals. Prior to the discussion of the individual proposals, the discussion briefly focuses on three factors that will underpin the viability of any international moves to enhance biosecurity, biosafety, and oversight of genetic engineering research. The first factor key to the success of any new standards will be the articulation of agreed lists of select human, animal, and plant pathogens. -

Agro Terrorism

Scienc al e tic & li P o u P b f Journal of Political Sciences & Public l i o c l A a f n f r a Manuel, J Pol Sci Pub Aff 2017, 5:2 i u r o s J Affairs DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000262 ISSN: 2332-0761 Research Article Open Access Agro Terrorism: A Global Perspective Manuel FZ* Angelo State University, Texas, USA *Corresponding author: Manuel FZ, Ph.D, Angelo State University, Texas, USA, Tel: 325-486-6682; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: May 25, 2017; Accepted date: May 31, 2017; Published date: June 06, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Manuel FZ. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The global food supply chain remains a significant target for those who want to cause fear, harm or destruction to our sustenance of life and liberty. When naturally-occurring animal outbreaks, such as foot and mouth disease, avian influenza, chronic waste disease, swine flu, or the many animal and crop diseases and pathogens are added to the list of potential security concerns and threats, biosecurity and bioterrorism assume a greater significance in a nation’s effort to effectively secure their homeland. Information and intelligence gathering, policy decisions, target hardening, and resource allocation become linchpins for effective homeland security. This paper discusses global agricultural security risks within the milieu of agro terrorism as a threat to biosecurity. -

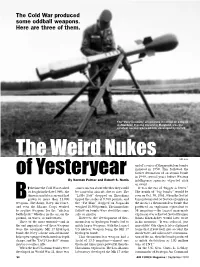

The Weird Nukes of Yesteryear

The Cold War produced some oddball weapons. Here are three of them. The “Davy Crockett,” shown here mounted on a tripod at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, was the smallest nuclear warhead ever developed by the US. The Weird Nukes DOD photo end of a series of thermonuclear bombs initiated in 1950. This followed the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb of Yesteryear in 1949, several years before Western By Norman Polmar and Robert S. Norris intelligence agencies expected such an event. y the time the Cold War reached some concern about whether they could It was the era of “bigger is better.” its height in the late 1960s, the be carried in aircraft, due to size. The The zenith of “big bombs” would be American nuclear arsenal had “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima seen on Oct. 30, 1961, when the Soviet grown to more than 31,000 tipped the scales at 9,700 pounds, and Union detonated (at Novaya Zemlya in Bweapons. The Army, Navy, Air Force, the “Fat Man” dropped on Nagasaki the Arctic) a thermonuclear bomb that and even the Marine Corps worked weighed 10,300 pounds. The immediate produced an explosion equivalent to to acquire weapons for the “nuclear follow-on bombs were about the same 58 megatons—the largest man-made battlefield,” whether in the air, on the size or smaller. explosion ever achieved. Soviet Premier ground, on water, or underwater. However, the development of ther- Nikita Khrushchev would later write Three of the more unusual—and in monuclear or hydrogen bombs led to in his memoirs: “It was colossal, just the end impractical—of these weapons much larger weapons, with the largest incredible! Our experts later explained were the enormous Mk 17 hydrogen US nuclear weapon being the Mk 17 to me that if you took into account the bomb, the Navy’s drone anti-submarine hydrogen bomb. -

The Multilateral Export Control Supplier Arrangements: NSG, MTCR, AG, and Waasenar WMD Acquisition Threat and Export Control Response

International Nonproliferation Export Control Program (INECP) Overview of the Multilateral Export Control Supplier Arrangements: NSG, MTCR, AG, and Waasenar WMD Acquisition Threat and Export Control Response COCOM Era Post-Cold War Era Iran USSR France Pakistan USA UK China India (Iraq) (Libya) S. Africa DPRK Technology Holders 2000 1980 1990 1950 1960 2004 2006 1970 1940 COCOM UNSCR 1540 Nuclear Suppliers Group Non-Proliferation Treaty Zangger Committee NSG Part 2 (Dual-Use NSG Part 1 (NSG Trigger List) List) Zangger Trigger List Australia MTCR Wassenaar Group Arrangement 2 The multilateral export control “regime” • Multilateral export control arrangements - Informal groups of like-minded supplier countries which seek to contribute to the non-proliferation of WMD and delivery systems through national implementation of Guidelines and control lists for exports. - Guidelines are voluntarily implemented in accordance with national laws and practices - Establish a set of global norms that limit the ability of proliferators to “shop” items and technology in countries that do not have export control systems in place • UN Security Council Resolution 1540 - Legally binding Chapter VII Resolution - Calls upon all States to take and enforce effective measures to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons and their means of delivery, including related materials, equipment, and technology covered by relevant multilateral treaties and arrangements. 3 Multilateral Export Control Arrangements Regime Established Participating -

A Journalist's Guide to Covering Bioterrorism

A Journalist’s Guide to Covering Bioterrorism Radio and Television News Directors Foundation News Content and Issues Project Published with the generous support of Carnegie Corporation of New York. Bioterrorism A Journalist’s Guide to Covering Bioterrorism By David Chandler and India Landrigan • Made possible by the generous support of Carnegie Corporation of New York Radio and Television News Directors Foundation • President, Barbara Cochran • Executive Director, Rosalind Stark Project Director, News Content and Issues, Paul Irvin • Project Coordinator, News Content and Issues, Michele Gonzalez Editors: Mary Alice Anderson, Loy McGaughy Project Advisers: Jerome Hauer, Dr. Phillip Landrigan, Scott Miller, David Ropeik. Copyright ©2002 by the Radio and Television News Directors Foundation (RTNDF). All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from RTNDF. Printed in the United States of America. The version of this guide that appears on RTNDF’s web site may be downloaded for individual use, but may not be reproduced or further transmitted without written permission by RTNDF. A JOURNALIST’S GUIDE TO COVERING BIOTERRORISM Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................3 Why This Guide Is Needed.....................................................................................................5 What Is Bioterrorism?.............................................................................................................7